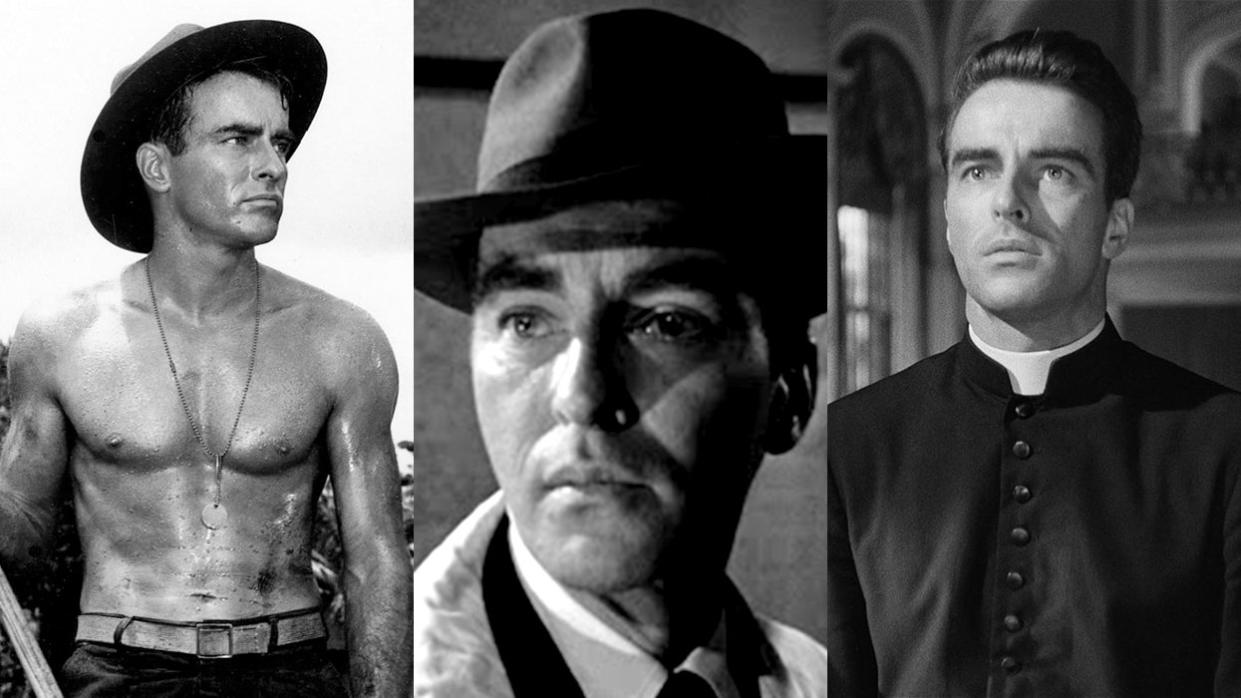

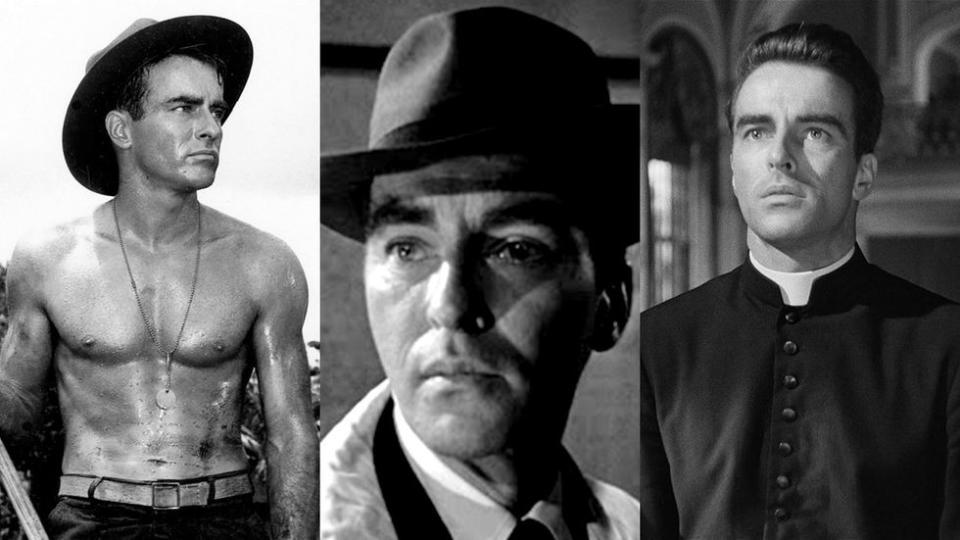

10 films showcasing the greatness of bi Hollywood icon Montgomery Clift

Columbia Pictures; United Artists; Warner Bros. Entertainment

Montgomery Clift was one of the most highly regarded — and most beautiful — film actors of the mid-20th century. He also was unabashedly bisexual, something that couldn’t be acknowledged in the press at the time, but in his social circles he was open about his relationships with both men and women. An image has emerged of him as depressive, self-destructive, and tortured about his sexuality, but a documentary released by his nephew in 2018, Making Montgomery Clift, takes issue with that. He had a brooding side, yes, and sometimes overindulged in alcohol and drugs, but he also had a fun-loving side and was comfortable with his sexual orientation, according to the documentary.

What’s not in dispute is Clift’s brilliance as an actor. He started on Broadway as a teenager, then moved into films in 1948, when he was in his late 20s. He didn’t amass a huge filmography, as he was extremely particular about the roles he took, and he died young — in 1966, at age 45. But his talent was unquestionable and his performances almost always excellent. He brought earnestness, sensitivity, and an appealing vulnerability to his portrayals.

One aside, before we take you through our film recommendations: Gay actor Craig Chester, a mainstay of 1990s New Queer Cinema, claims to have been haunted by Clift’s ghost. He’s talked about the haunting on public radio programs, which you can listen to here and here.

Now, scroll on for 10 of Clift’s best films, in chronological order.

Pictured, from left: Clift in From Here to Eternity, Lonelyhearts, and I Confess

Red River (1948)

United Artists

Clift isn’t particularly associated with Westerns, but he made his screen debut in one, Red River. It’s a good film, helmed by esteemed director Howard Hawks. Clift is Matt Garth, who rebels against his tyrannical adoptive father, Tom Dunson (John Wayne), during a cattle drive. It features fine performances and lots of beautiful vistas, and don’t miss the homoerotic scene in which Clift and John Ireland compare their gun barrels. That sequence was highlighted in The Celluloid Closet.

The Heiress (1949)

Paramount Pictures

The Heiress is a superb film, featuring another tyrannical father — this time Dr. Austin Sloper, played by Ralph Richardson. He’s father to Catherine, the “plain” and na?ve heiress of the title (like Olivia de Havilland ever wasn’t beautiful), and he’s disapproving of her relationship with Clift’s Morris Townsend, as he suspects Morris is only after her money. It’s a great drama of complicated and often manipulative characters, set in 19th-century New York City. Ruth and Augustus Goetz wrote the screenplay, based on their Broadway play, which they adapted from Henry James’s novel Washington Square. William Wyler directed, and de Havilland won the Best Actress Oscar for playing Catherine.

A Place in the Sun

Paramount Pictures

Monty Clift. Elizabeth Taylor. Almost too much beauty for the screen to contain. A Place in the Sun is a poignant drama based on Theodore Dreiser’s novel An American Tragedy, with Clift as factory worker George Eastman, who aspires to a higher social echelon and is besotted with wealthy college student Angela Vickers (Taylor), but finds his ambitions frustrated by the pregnancy of his girlfriend from the factory, Alice Tripp (Shelley Winters). The film brought Clift an Oscar nomination for Best Actor, while director George Stevens and screenwriters Michael Wilson and Harry Brown scored Oscar wins.

I Confess (1953)

Warner Bros. Entertainment

I Confess was Clift’s only film for Alfred Hitchcock. It’s not one of Hitch’s best, but even lesser Hitchcock is well worth seeing. Set in Quebec City and shot mostly on location there, it has Clift as Father Michael Logan, a Catholic priest who hears the confession of a murderer and has a moral dilemma because bringing the man to justice would violate the sanctity of the confessional. Karl Malden is on hand as a police detective and Anne Baxter as a woman who was involved with Michael before he took his vows and is still in love with him.

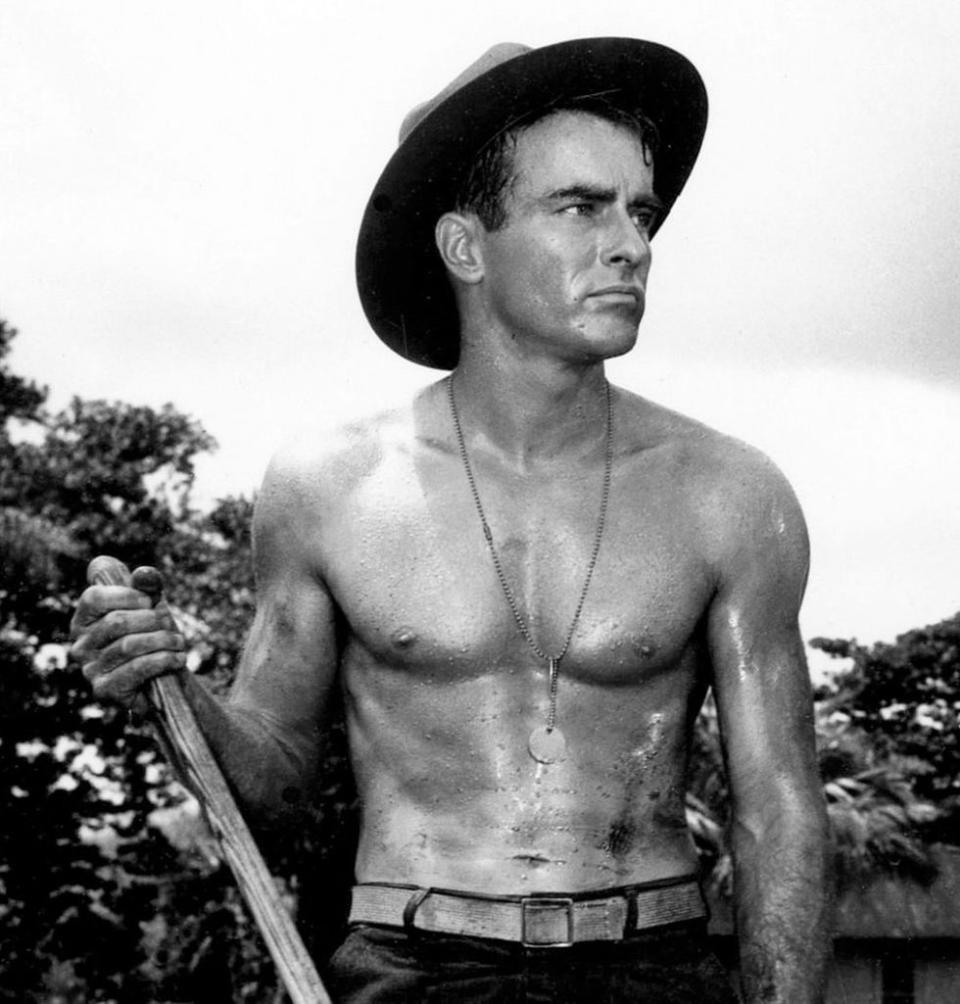

From Here to Eternity (1953)

Columbia Pictures

From Here to Eternity was one of the biggest movies of 1953, winning eight Oscars, including Best Picture. Clift was nominated for Best Actor and didn’t win, but his portrayal of Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt is nonetheless stellar. The film, adapted from James Jones’s novel, follows Prewitt and other soldiers stationed at an Army base in Hawaii just before Pearl Harbor, along with the women in their lives. Prewitt is principled and stubborn; he’s a skilled boxer, and he’s told he can hope for advancement only if he joins the base boxing team, but he refuses because he once blinded a man in the ring. He holds to his position despite severe harassment and meanwhile romances “nightclub hostess” Lorene (Donna Reed), who was a sex worker in the novel. The starry cast also includes Burt Lancaster, Deborah Kerr, and Frank Sinatra, and yes, there’s that famous scene of Lancaster and Kerr embracing on a beach as the waves wash over them. Screenwriter Daniel Taradash’s adaptation of the novel toned down the sex and the suggestion that the Army was corrupt, but the film, directed by Fred Zinnemann, was still considered pretty sensational for its time. Another Clift ghost story: It’s said that he practiced bugling, another of Prewitt’s skills, in a room at the historic Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, and you can hear the sound of a ghostly bugle there.

Raintree County (1957)

MGM

Many critics have deemed Raintree County a failure, an unsuccessful attempt to outdo Gone With the Wind as a Civil War saga, but there are numerous fans who love it, including this writer. The movie is based on the only novel by Ross Lockridge Jr., who died by suicide at age 33. Clift is John Shawnessy, an Indiana abolitionist who marries visiting Southern belle Susanna Drake (Clift’s great friend Elizabeth Taylor) and tries to cope with her mental illness; he also still loves his hometown sweetheart, Nell Gaither (Eva Marie Saint). The film follows them through the end of the war and features able supporting performances from Nigel Patrick, Lee Marvin, and Rod Taylor. One night during the shoot, Clift attended a dinner party at Taylor’s home and had a serious auto accident driving away, resulting in much damage to his beautiful face. Upon recovery, his looks were a bit rougher, less delicate, but he remained a very handsome man.

Lonelyhearts (1958)

United Artists

Lonelyhearts, adapted from Nathanael West’s Depression-era novel Miss Lonelyhearts, has Clift as newspaper advice columnist Adam White, who’s deeply affected by the sad letters he receives. One of his correspondents, Fay Doyle (Maureen Stapleton, Oscar-nominated), makes romantic advances to him in person, while he has a sweet, earnest girlfriend in Justy, played by Dolores Hart, a promising young actress who left Hollywood to become a nun. In support are the always-reliable Robert Ryan as a tough editor and the great Myrna Loy as his unhappy wife, who's befriended by Adam.

Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

Columbia Pictures

Suddenly, Last Summer is based on a Tennessee Williams play, and it has all the gothic drama associated with his work. Elizabeth Taylor, in her third teaming with Clift, is Catherine Holly, a young woman who, while recovering from being raped, was sent abroad with her cousin Sebastian, now deceased. Spoiler alert: He turned out to be a pedophile using her to attract young boys. She’s had a breakdown, and now she’s in a mental hospital. Sebastian’s mother, Violet Venable (Katharine Hepburn), whom eccentric does not begin to describe, wants Catherine lobotomized to keep the truth about her son from coming out. But Catherine finds a sympathizer in Clift’s Dr. Cukrowicz. Gore Vidal adapted Williams’s play for the screen, and Joseph L. Mankiewicz directed. The drama behind the scenes nearly matched that on film: It’s been reported that Clift had many difficulties while making the movie — he was drinking heavily, for one thing — and Hepburn thought he was seriously mistreated by Mankiewicz. She’s said to have spat in the director’s face when the shoot ended.

The Misfits (1961)

United Artists

The modern Western The Misfits was the last film for both Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable, and Clift would make only three movies after it. Written by Monroe’s then-husband, Arthur Miller, and directed by John Huston, it has Monroe as Roslyn, a recent divorcée wondering what the rest of her life holds; Gable, Clift, and Eli Wallach as the men who are drawn to her; and the always-watchable Thelma Ritter as Roslyn’s landlady and friend. The men are also on a mission to capture some wild mustangs. The film has an elegiac quality that’s only heightened by the knowledge of its stars’ fates.

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

MGM

Judgment at Nuremberg is a star-studded treatment of the post-World War II Nazi war crimes trials, directed by Stanley Kramer, well known for his socially conscious films. Clift gives a much-praised performance as a mentally challenged man who was forcibly sterilized by the regime and tells his story on the witness stand; he received his fourth and final Oscar nomination for the role. The cast also includes Spencer Tracy as the judge; Richard Widmark and Maximilian Schell as the prosecutor and defense attorney, respectively; and Burt Lancaster, Judy Garland, and Marlene Dietrich.