5 York County brothers who served during WWII all came home. But the war took its toll

Edith Jacoby maintained a stiff upper lip.

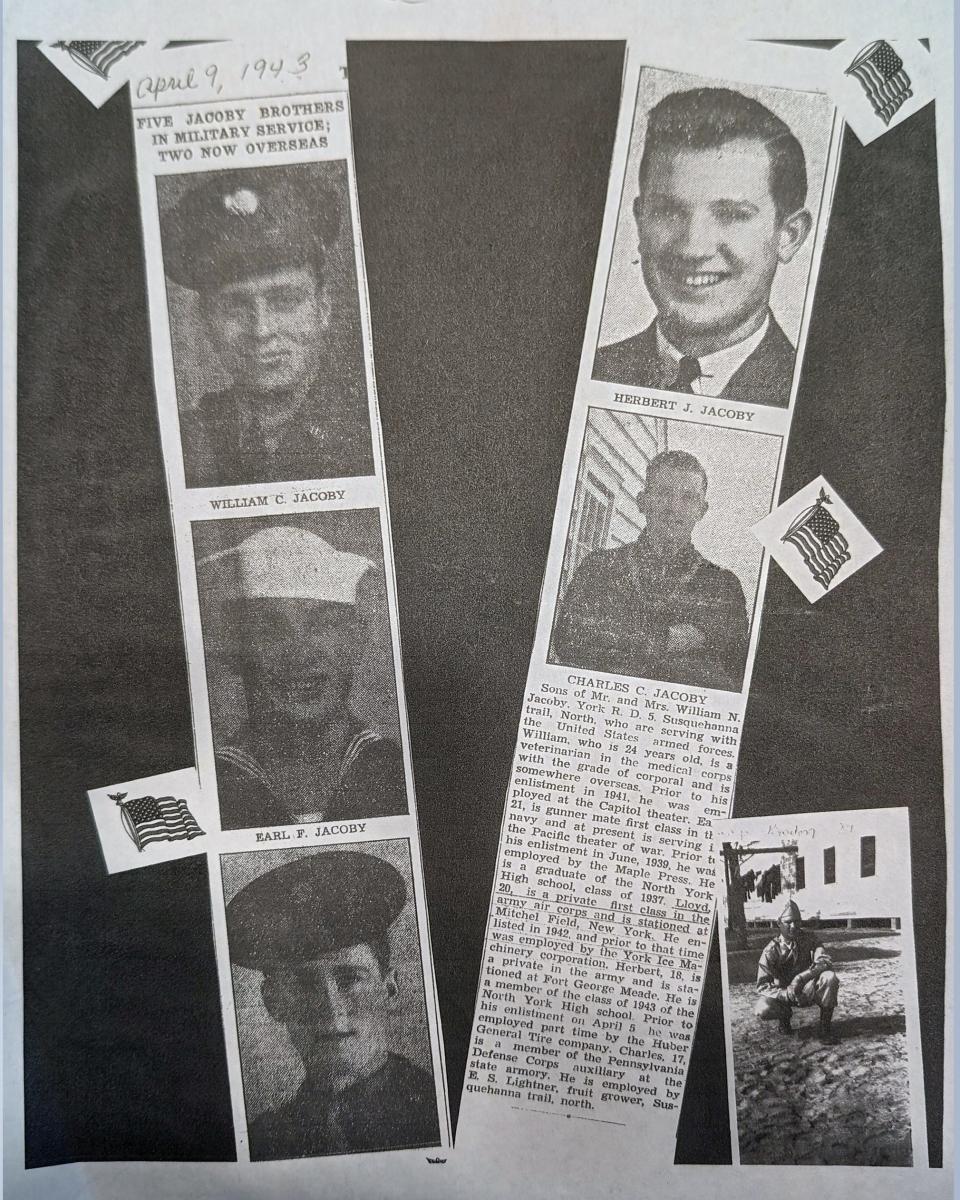

During the height of World War II, five of her 10 sons – she also had four daughters – served in the military, all of them dispatched all over the world engulfed in the conflict.

While her boys were overseas, Edith would lead expeditions into downtown York, which was quite an excursion from their homestead north of town. She and her daughters would buy candy bars and cookies and other treats to box up and send to the boys serving in the Pacific and the Atlantic theaters.

Edith never let on that she worried about her boys. For one thing, her youngest daughter, Mary, recalled, she was too busy. She ran the household and, in those days, it was more than full-time work. She didn’t talk about her worries or her feelings much. You didn’t do that, and as Mary said much later, she was “too busy.”

“I don’t know how she did it,” Mary said recently. “Dad, he couldn’t let it bother him as much. He had a business to run and was farming.”

Her son Earl wrote of his mother years later, “She must have had nerves of steel.”

Edith, though, found time to worry, even if she didn’t let on about it.

It wasn’t until after the war – until her sons had come home – that it hit her.

And it hit her hard.

'Brothers in arms'

It was not unusual during World War II for families to have more than one son serving in harm’s way. There are families whose stories have been chronicled by the Library of Congress who had four, five and six sons serving in the military during wartime. One such story, based on the service of the four Niland boys from Tonawanda, New York, formed the basis of Steven Spielberg’s 1998 film “Saving Private Ryan.”

A number of families lost their sons in combat, most notably the Sullivans of Waterloo, Iowa. On Nov. 13, 1942, five Sullivan brothers were serving together on the light cruiser the USS Juneau when the ship was struck by a Japanese torpedo and sunk. All five – George, Frank, Joe, Matt and Al – perished. (Their story would have a tangential connection to the experience of one of the Jacoby boys.)

The Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project recorded several of the stories of families who served during the war. The Jacoby boys were not among them.

The introduction to the library’s research states, “Oftentimes, veterans speak about their military units as if they were families, given the tight bonds that develop between comrades. But for some veterans, “brothers in arms” is more than a figurative turn of phrase. During the 20th century, war frequently touched multiple relatives and generations of the same family.”

Growing up poor

The Jacoby family was poor, Earl Jacoby, one of the 10 sons, wrote in his memoirs. His father, Norman, had a butcher business just north of York and in the early 1920s bought a 135-acre farm near Fink’s Corner in Zion’s View. “In the boonies” is how Earl described it. The small farmhouse serving as home to a family of 16, heated by a wood stove.

Growing up on the farm was hard. All of the children worked the farm between attending classes at the two-room schoolhouse off the Susquehanna Trail. Earl recalled one afternoon when his father was plowing a field and to start the first furrow, he lined up the boys in a straight line to mark it. One of the neighbor boys had a .22-caliber rifle with him and shot it down the line to make sure everyone was in a straight line. The bullet struck Earl’s older brother Bob in the chest, entering his body an inch below his heart and exiting through his back. Earl recalled they took Bob to the doctor, who poked a wooden dowel through the wound. The doctor patched him up and the next day Bob was back outside, playing and working on the farm.

The family made its living butchering cattle and truck farming, selling produce in town on Saturday mornings during harvest season. The butcher shop still stands behind the family house, the retail operation in front, the icebox that consumed a ton of ice a week along the back wall, the area where the cattle were led into the building to be slaughtered, the sluice to drain away the blood still in the middle of the floor by the ring used to secure the animal. Wayne Jacoby, the youngest boy, remembers one steer getting away and his father using a shotgun to bring it down.

Earl recalled that while his father was busy, he and his mother would tend to the produce garden and milk the 10 to 20 cows they had. Every morning before heading off to school Earl and his siblings would carry the milk cans to the road, a half-mile away, to be picked up and taken to a creamery.

The boys would spend their days baling hay or cutting firewood or tending to their trap lines, catching mink, raccoon, skunk, possum, muskrat or weasel for the pelts, which would sell for $1 or $3, depending on the quality of the fur.

“The only reward for our hard work was being served beer, lemonade and soft drinks; beer if you were old enough or if your parents weren’t watching,” Earl wrote.

Earl recalled that his father, lubricated by whiskey provided by the dealer, bought a seven-passenger sedan in the early 1930s. Prohibition was in effect, but car dealers found that it was easier to close deals if they sweetened the deal with liquor. On one Sunday drive, Earl wrote, he was riding in the backseat, playing with the door handle when the door swung open, and he was flung onto the pavement. He was knocked unconscious, his head split open. His grandparents treated his wounds with lilac soaked in whiskey. It stung, he recalled.

The family’s farm days ended during the Great Depression. “The horses and equipment were worn out, they said, along with their credit,” Earl wrote.

They moved back to the homestead closer to the city and concentrated on the butchering business.

The rootlessness was contrary to the family’s deep roots. Edith’s mother was Minnie Eisenhower, a second cousin to Dwight Eisenhower, the family emigrating from Germany in the 1770s or so. They had been on this land for centuries.

During World War II, like their distant cousin, the family established a different history, one of serving their country.

Headed to a day of infamy

Earl was the first to go into the service.

He had been working at Maple Press, making eight dollars a week, before he enlisted in the Navy in 1939. It wasn’t so much patriotism – the country was still two years away from being at war – as it was a means of escape. “He had a mind of his own,” Wayne said. “He wanted to get out and didn’t want to follow what his parents were following. I think he and my dad had a few problems.”

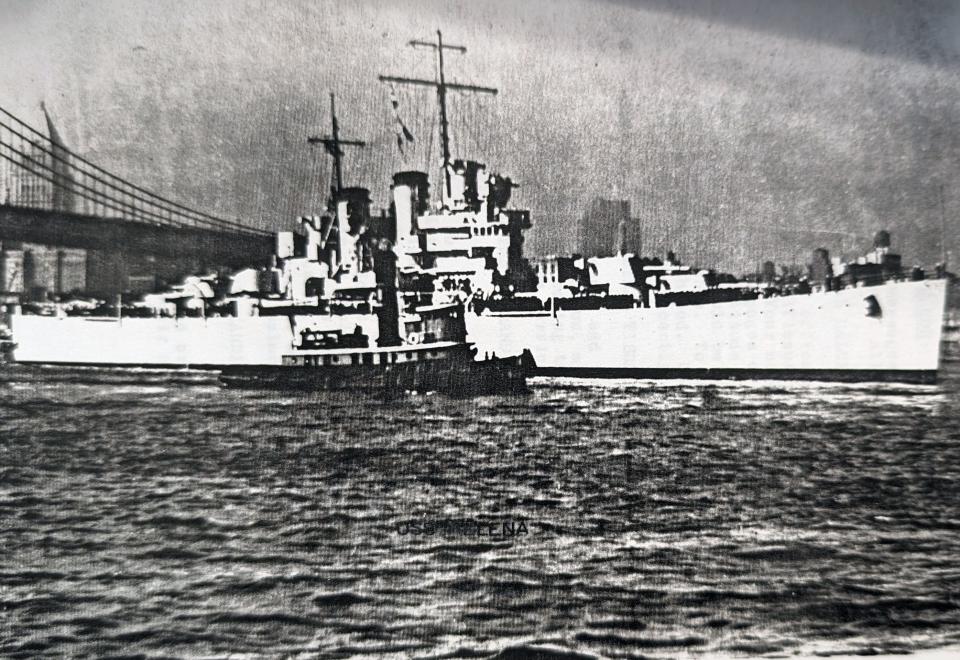

After basic training, he shipped off to the Brooklyn Naval Yard, where he was assigned to the crew of the newly commissioned light cruiser the USS Helena, a gunner’s mate. The ship’s shakedown cruise took it from New York to Norfolk and South America. While in Argentina, Earl met members of the crew of the German battleship the Graf Spee, which sought asylum in South America after scuttling the ship off the shore. “As I spoke with the Germans, I found out there were just as ‘human’ as we were; however, I had a funny feeling we would be fighting in their homeland in due time,” Earl wrote. “I never had any hang-ups as to whether or not we would be in World War II. It would be just a matter of time.”

After South America, the Helena cruised to Cuba and then Panama, through the canal, to the Pacific for its destination – Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

The boys head to war

Earl’s older brother, Bill, was the next to enter the service. He served with the Army Cavalry in Burma, defending the Chinese from the Japanese. The family doesn’t know much about his service, other than he worked with horses. They have an old photo of his, skinny as a fence post, holding a painted pony in the tropics.

Lloyd, a year and a half older than Earl, was drafted in 1941 and assigned to the Army Air Corps. He was a quartermaster, part of the logistics team feeding supplies to front-line troops. He served on a ship supporting the D-Day invasion and spent some time in Normandy, after the invasion, setting up supply lines to troops working their way through western Europe toward Germany.

Herb, four years younger than Earl, went into the Army, leaving for the service before graduating high school. He was assigned to the motor pool and served as a chauffeur to an officer in Hawaii. “He had the best racket of any of them,” his brother Wayne said.

Charlie, five years younger than Earl, joined the Navy in 1943, serving on so-called Liberty Ships, merchant marine ships that moved supplies across the Atlantic to troops in the European Theater. At first, Wayne said, it was risky duty, as German U-boats patrolled the Atlantic, looking to torpedo merchant ships and disrupt supply lines. Later, though, the duty was fairly safe.

It was clear Earl’s four brothers would make it home.

For Earl, it was not so certain.

'I lost quite a few of my friends'

On Dec. 6, 1941, Earl spent the night with “a cute little Wahini – all breasts and thighs.” He wrote, “She gave me a come-hither look, asking why must I go back to the ship when I could spend the night with her.”

He returned to the ship at 4 the following morning and hit his rack aboard the Helena. He was awakened by an announcement over a loudspeaker. He was still a bit groggy but, years later, he distinctly remembered the words: “General Quarters: Japanese planes are bombing Ford Island. This is not a drill. This is for real.”

“At practically the same moment, there was a terrific explosion aboard ship,” he wrote. “I ran forward in the passageway to get to a ladder leading topside and to my battle station – the anti-aircraft guns. This was it.”

The Helena took a torpedo to its forward engine room, he wrote. The explosion sent a fireball through the ship. Earl dove under some bunks to keep from being incinerated.

He watched as Japanese dive-bombers devastated the U.S. fleet. “I saw the Arizona blow up, followed by the Oklahoma and the Maryland,” he wrote.

The dead and wounded littered the deck, he wrote. Japanese fighter strafed the deck as the crew tried to get to battle stations. “Between the battles,” he wrote, “we took care of the injured and carried them down the gangway and into awaiting ambulances. Some of the men were severely burned. As we helped those who were suffering from the burns, sometimes their skin and even their flesh would come off in our hands.”

The attacks subsided at about 11 a.m., he wrote, “and I was able to get dressed. Up until that time, I was like Tarzan fighting in a pair of boxer shorts. I was able to endure the entire attack without being wounded.”

He wrote, “I lost quite a few of my friends that morning. It was a grisly mess.”

'Saved and free again'

The Helena was dispatched stateside for repairs and while in San Francisco, Earl met a girl named Chi-Chi in Oakland. He liked her and hung out with her, and when the Helena shipped out in July 1942 to rejoin the fleet, Chi-Chi and her mother continued to write to him. “They were talking marriage,” he wrote. “Up to that point in time, my mode of operation was to find them, love them, enjoy them and leave them.”

One day, he wrote, he received a “Dear John” letter from Chi-Chi's mother. The woman had run off with a sailor, she informed him. “Her mother was heartbroken, but I was relieved,” Earl wrote. “I was saved and free again.”

'A keg of dynamite'

The Helena returned to duty and steamed toward Guadalcanal, Earl wrote in his memoirs. Early on, he wrote, the fleet lost three cruisers in one engagement. He recalled one encounter when a Japanese dive bomber was homing in on the Helena with a Hellcat on its tail. The Hellcat shot down the Japanese plane and then, unable to pull out of its dive, plunged into the Pacific.

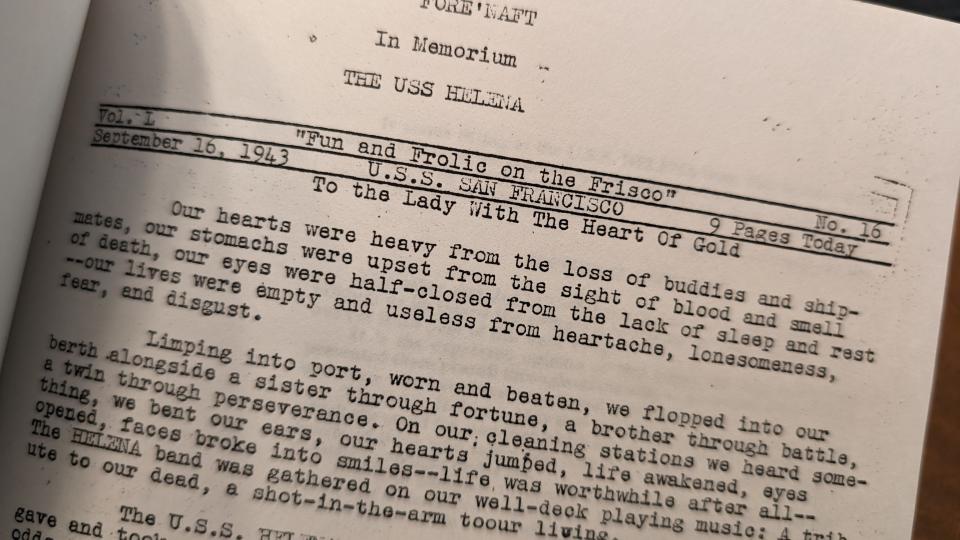

During one of the battles, he wrote, a torpedo aimed at the Helena missed and struck the USS Juneau, hitting its ammunition magazines and causing the ship to blow up “like a keg of dynamite,” Earl wrote. “When the smoke lifted, the only thing that was left was a calm ringlet that looked like someone had just thrown a stone into the water.” Only seven of the crew of 750 survived. The five Sullivan brothers perished.

Turning war trauma into art: York Vietnam vet's haunting, powerful sculpture reflects the horrors he experienced in war

More about WWII vets: York WW II veteran and POW, 100, shares harrowing tale of being shot down over Germany

During the early morning hours of July 6, 1943, the Helena was joined in the Battle of Kula Gulf. During the battle, three torpedoes slammed into the ship’s hull.

“We were sinking when I swam off the main deck,” Earl wrote. “I spent several hours in the water before I managed to get aboard a life raft that was covered in fuel oil. The night was still and occasionally, we could hear a voice or see a flashlight, but basically, we were alone in the Kula Gulf area of Georgia Island, one of the Solomon Islands.”

The tide dragged the raft toward the shore, where Japanese troops were bivouacked. Earl wrote those on the raft paddled away from shore and into the ocean. One-hundred and sixty-eight members of the 900-member crew did not make it.

Earl made it, rescued by the destroyer the USS Radford.

He wound up in Australia.

And eventually he made his way home.

The toll of war

The war took its toll.

Most of the brothers were fine.

Lloyd was a lifelong bachelor, working at what had been Allis-Chalmers – now, Voith Hydro – west of York. The last few years of his life, he worked at the now-defunct Jay’s Supermarket in York and lived in a trailer that was packed with old lottery tickets and papers, his brother said. He died in 2005.

Charlie worked briefly for Allis-Chalmers and then went into business as a carpenter. He played the tuba with the Zion’s View Band, and later the Emigsville Band, for years before his passing in 2009.

Herb returned from the service and worked as a mechanic, operating Jacoby’s Garage for years. He died in 2016.

Bill returned from the service a changed man. His daughter said he suffered from what would be now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder but then was called shell shock. His wounds couldn’t be salved by whiskey-lilac leaves. “It affected him the rest of his life,” his brother Wayne said. He never drove a car and didn’t want to travel much. He worked as a machinist at the old Naval Ordnance Plant – now Harley-Davidson – until his retirement. He died in 1988.

Earl came home and went to the University of Pittsburgh on the G.I. Bill, earning a degree in engineering. He worked in the Pittsburgh area and eventually retired to a farm in Hillsboro, Ohio, in 1982. He died in 1998.

'Don't know how she did it'

After all her sons returned from the war, Edith had a breakdown, her daughter said.

Her family thinks that she just kept all of her worry bottled up during the war and when it ended, well, it hit her hard. “She just broke down after,” her daughter Mary said.

Edith spent some time in a hospital in Philadelphia, Mary said.

“She got squared away,” she said.

She managed to keep her wits about her during the war, something that her daughter doesn't quite understand.

She said, “I don’t know how she did it.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: 5 York County PA brothers survived WWII, but the war took its toll