82 schools have removed their racist namesakes since 2020. Dozens now honor people of color.

It wasn’t until her junior year that Ashley Sanchez-Viafara learned the truth behind her high school’s racist namesake.

The Thomas Chambliss Williams high school in Alexandria, Virginia, was named after a longtime district superintendent who served during the civil rights era — and did everything he could to preserve segregation.

“The name wasn’t really talked about, and when it was, it was only in a positive light,” said Sanchez-Viafara. T.C. Williams High inspired the 2000 biographical sports film "Remember the Titans" starring Denzel Washington — based on a true story about the school football team’s struggles with integration. Alumni were attached to the name and the memories it conjured.

One of two student representatives on the Alexandria City Public Schools board, Sanchez-Viafara thought there had to be a better name than that. She and her peers got to work on a campaign that led to the school's name being changed to Alexandria City High in 2021.

More than 80 public schools across the United States chose to drop their namesakes in the aftermath of George Floyd's murder in May 2020, citing the individuals’ racist acts, according to a USA TODAY analysis of federal data.

“It’s all part of this power struggle around the schoolhouse,” said Hilary Green, the James B. Duke Professor of Africana Studies at Davidson College. She studies Confederate monument removal and school renaming trends. Green said she expects the country will continue to see an increase in the number of schools abandoning racist namesakes.

Schools abandon Confederate, presidential namesakes

Hundreds of Confederate monuments fell nationwide as local officials vowed to eradicate symbols of racism in their communities. School names were among the most visible.

Only months after the racial justice protests of 2020, school board officials faced a flood of appeals to remove racist namesakes from school buildings, and prominent Confederate figures were an immediate target in Southern states.

Robert E. Lee, a leading Confederate general, had his name removed from 17 schools; Stonewall Jackson, another general, from eight schools; and Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s president, from four.

In Northern states, according to a review of federal data, very few schools had Confederate namesakes. But many school boards voted to drop names of controversial presidents, such as James Buchanan, who failed to challenge the spread of slavery immediately preceding the Civil War; and President Woodrow Wilson, who doubled down on segregation and openly supported the Ku Klux Klan.

Hundreds of schools nationwide are still named after controversial presidents and well-known Confederate figures, however.

Map of schools that have changed their names since 2020

Confederate statue removal: Nearly 100 eliminated in 2020 — but hundreds remain

From Robert E. Lee to John R. Lewis: School in Virginia gets a name change

Some names were more obscure

School name changes involving Confederates may have been the most visible because they’re so well known, but they were far from the only controversial names targeted in the nationwide push to jettison racist symbols.

In Minnesota, two schools removed the name Henry Sibley, a Civil War era governor, after activists brought to light evidence that he massacred Native Dakota people.

In Illinois, school board officials eschewed the name Daniel Webster, a former secretary of state who defended slavery.

And in Wilmington, North Carolina, the school board voted to remove the name Walter L. Parsley, a previously obscure historical figure who engineered a coup that left scores of Black residents dead.

More: How one North Carolina school rejected its white supremacist namesake

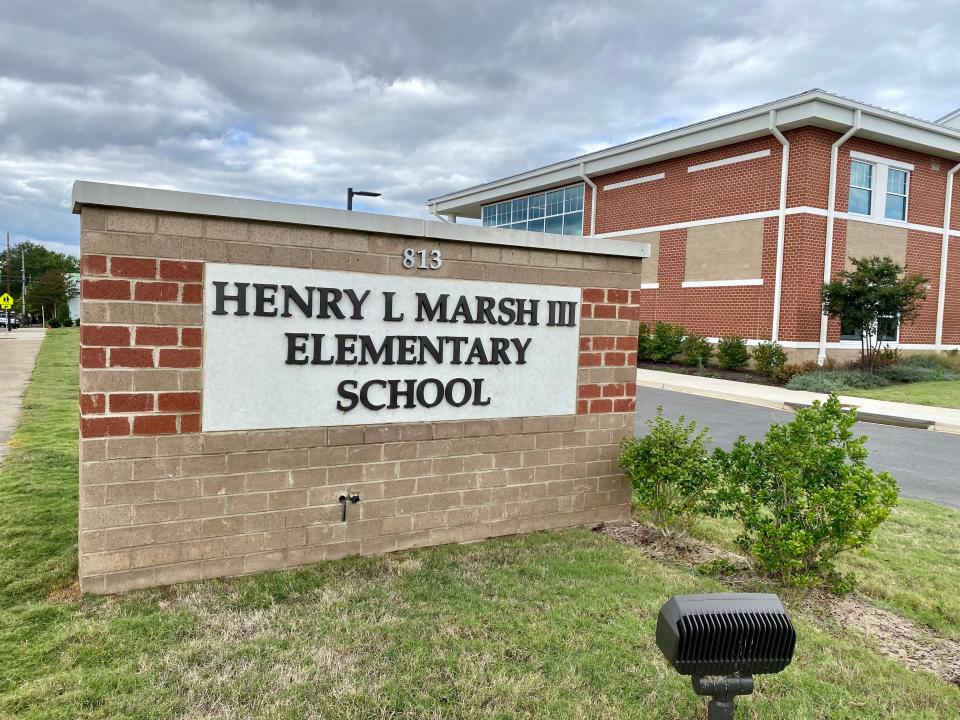

Roughly half of the schools in USA TODAY’s database were renamed after people, nearly all of them people of color. Of those 82 schools, 27 now honor women.

On average, the schools that have changed their names since 2020 serve student populations that are two-thirds nonwhite.

USA TODAY’s database doesn’t capture schools that have changed their names since January 2022. They include Jackson Reed High School in Washington, D.C., formerly known as Woodrow Wilson High.

Look up which schools area changed their names

If you cannot see a data search tool below, click here.

'The names we pick matter'

Back in Alexandria, amid the wave of global unrest and greater scrutiny of systemic racism, Sanchez-Viafara and her peers learned that a number of other schools in the area had recently undergone name changes or were in the process of doing so. “We were given an opportunity to just look at how we wanted to redefine ourselves,” Sanchez-Viafara said.

The now-college sophomore helped spearhead what would become known as the district’s Identity Project, a painstaking yearslong initiative to replace the segregationist namesake with one that better reflected the school’s diverse population today. The initiative sparked a similar movement at the nearby Matthew Maury (now Naomi L. Brooks) Elementary School. Maury was an oceanographer and U.S. naval officer who fought for the Confederacy, and Naomi Brooks, a former teacher who fought segregation as a student.

After reviewing and debating scores of submissions and dealing with their fair share of hostility from adults in the community, Sanchez-Viafara and her peers settled on Alexandria City High School. There’s only one public high school in Alexandria; students come from all over the city.

Virginia – which had the second-highest number of schools (24) with Confederate namesakes in 2019 – accounts for nearly one-third of the schools that have changed their names since George Floyd was murdered in police custody in Minneapolis in 2020.

“The names we pick matter,” said Jay Greene, a senior research fellow at the right-leaning Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy. “Communities should use the opportunity of naming their schools as a way of conveying to their children the values they hold dear, and the people they think help represent those values.

“It’s a way of expressing to their children, ‘These are the people who we think you should be thinking about and studying and discussing and maybe in some ways emulating.’”

That symbolism can have real consequences for students of color when the namesake was someone who believed in and promoted the enslavement or oppression of their ancestors, Davidson’s Green said.

Students have told Green that their school’s decision to change its name persuaded them not to drop out and to apply themselves in class.

But renaming initiatives have in many cases led to fiery conflict often coinciding with attacks on history curricula and inclusion efforts.

“Renaming can be a way to heal and move forward, but if it’s not done right can bring us back to this really polarizing place,” said Green, of Davidson.

Take what happened 120 miles west of Alexandria, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

In the summer of 2020, then-Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam, a Democrat, issued a letter to school boards across the state calling on them to rename schools honoring Confederate leaders. “When our public schools are named after individuals who advanced slavery and systemic racism, and we allow those names to remain on school property, we tacitly endorse their values as our own,” he wrote.

The letter, coupled with grassroots efforts, some of them already years in the making, spurred school boards across the state to begin the renaming process. Among them: the board overseeing Shenandoah County Public Schools, a rural, predominantly white district where two schools bore Confederate names: Ashby-Lee Elementary and Stonewall Jackson High.

The board quickly renamed them – to Honey Run Elementary and Mountain View High. For a while, that was that.

But then, in 2022, thousands of community members, including alumni, signed a petition demanding a return to the old names. The name changes were described as “elitist” and “creepy.” The school board, which since the renaming decision had grown more conservative, entertained the demands but ultimately voted to keep the new names.

Observers worry more such dust-ups will emerge as more schools are renamed and culture wars continue to dog education. Last spring, the San Francisco school board walked back a highly controversial plan to rename 44 schools honoring figures with questionable legacies, from George Washington to Paul Revere to Dianne Feinstein.

Photos: Robert E. Lee Confederate statue removed in Richmond, Virginia

Bye Lincoln and Washington?: San Francisco voted to rename 44 schools for namesakes' ties to racism, slavery.

And one upshot could be more school boards opting for generic names like Honey Run and Mountain View. Nearly half of schools that eschewed controversial namesakes chose new names that don’t honor a person but instead reflect geographic markers or other generic features.

“What we're seeing are more schools with vague nature names that sound more like herbal teas or day spas,” lamented the Heritage Foundation’s Greene, who more than a decade ago wrote a report for another conservative think tank documenting a steep decline in the number of schools being named after presidents and people in general.

In cities including Wilmington, North Carolina, school board officials have even passed policies that ban naming schools for people.

According to Greene, both the challenge and beauty of naming schools after people, whether it’s a popular local teacher or a wealthy donor or a civil rights icon, is that the decision is always going to be controversial. Everyone is flawed.

“And because people are flawed, there will be a fight about whether those flaws are tolerable or not,” Greene said. “There will also be a dispute about whether that person who’s being honored is more worthy than another person who could be (honored).

“This is really a fight over community values: What do we think is more important?”

Greene said he appreciates the desire to remove namesakes with problematic pasts and supports renaming efforts that strive to honor another person rather than resorting to something more innocuous and generic. In his view, the debates that result are constructive as they enable communities “to hash out, what do we want to teach our children?”

“Some fights are important because they’re really the way that a community decides what it wants to teach its children.”

Calls for changing racist school names aren’t new

Society’s decisionmakers have long understood the symbolism of school names – and, relatedly, of public monuments, buildings and other spaces.

Many of the Confederate-inspired school names were adopted during the civil rights movement amid efforts at school integration. It was a way for segregationists to assert their worldview, Davidson’s Green said.

Calls for removing those namesakes have been around for nearly just as long, according to Green, especially at the schools whose once predominantly white student populations grew more Black and brown over the years.

Floyd’s murder “accelerated the conversation,” Green said, referring to racial justice activism that had been picking up momentum since the mass shooting in a Black church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015 and the “Unite the Right” rally by white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 that left one person dead. “A generation of individuals who protested that finally had their voices heard in the 2020 moment. … Sadly, Charleston and Charlottesville weren’t enough.”

These days Sanchez-Viafara, the Alexandria student, is studying political science and sociology at nearby George Washington University. Looking back, she says, her experience on the Identity Project has been formative, and not only because it inspired her choice of majors.

“When we talk about racial justice, and we talk about activism, there’s often a sense of futility that comes with it, and a sense of cynicism. … We see that something needs to be changed but nothing gets done. That was one of the first moments in my life where I started change, I worked toward the change, and then I ended up seeing it.”

Your life in data: See crucial databases that can help you make everyday decisions

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

Contact Neena Hagen at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @neena_hagen.

How we did this story: USA TODAY built a database using public school directory files from the National Center for Education Statistics comparing information from the 2019-20 school year with the 2021-22 school year, the most recent year for which school name data is available. We analyzed thousands of rows of data to distill which schools’ names had changed. Reporters then combed through each entry manually to discern the reasons for the change and through original reporting and a review of local news publications, put together a picture of what happened in each case.

The NCES data is current as of December 2021, meaning schools renamed in 2022 were excluded from this database. There were also instances where school boards approved name changes, but the new official name had not yet been submitted to the NCES – these changes also were excluded. Name changes that weren’t the result of any local controversy were also removed.

Are there any controversial school name changes you think we missed? Tell us.

This database will be updated when NCES data from the 2022-23 academic year is released.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 82 schools renamed from Confederate generals to civil rights icons