An African American holiday predating Juneteenth was nearly lost to history. It's back.

NEW YORK – Cheyney McKnight waited years to celebrate Pinkster.

On a scorching Saturday morning in May, McKnight put on her tailor-made 18th-century Malian mud cloth dress and trekked 7 miles with a dozen others to partake in a storied tradition. The group rattled shell shakers and tambourines and beat drums, strolling New York City sidewalks from an old farmhouse near the top of Manhattan to the New-York Historical Society, recreating a route free and enslaved Black people would have traveled in colonial times on Pinkster, Dutch for "the Pentecost." The festival, which falls in May or June, follows Easter. It honors the Holy Spirit inspiring Jesus Christ's disciples to initiate the church's missionary work.

Pinkster is among an array of lesser-known African American holidays, although historians say it is likely one of the earliest. As the broader U.S. population prepares to honor Juneteenth, a federal holiday marking the day enslaved people in Texas learned belatedly about emancipation, McKnight and fellow celebrants drew the attention of pedestrians and commuters to the celebration of community some New York lawmakers hope may gain official recognition.

“There’s nothing like family,” McKnight told a small crowd that morning, as the day's events began at the farmhouse's porch. Recalling what Pinkster would have been like in colonial New York, she said, “These people came together every year to congregate, to just have a good time. This shows their agency.”

A New York lawmaker has a measure pending at the state Capitol – built atop a historic Pinkster gathering space – to enshrine Pinkster in state law alongside Juneteenth and Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Assemblymember Brian Cunningham, a Brooklyn Democrat who authored the bill, recently learned about the holiday and now considers Pinkster a key part of his state's history. He says it's essential the government recognize Black Americans not just in pain or hardship, but also in joy and family. Even during the hardest moments of enslavement, he said, “We still found moments to come together and celebrate our collective history.”

African American experience: Several Black museums have opened in recent years with more coming soon. Here's a list.

Juneteenth, which Black families have celebrated for generations dating back to Reconstruction, became one of a dozen federal holidays in 2021. However, it is not the only African American holiday to gain recognition. There are others, such as Negro Election Day, the day Black New Englanders elected community representatives, predates the American Revolution and is a Massachusetts holiday.

Slavery was 'regular part of New York life'

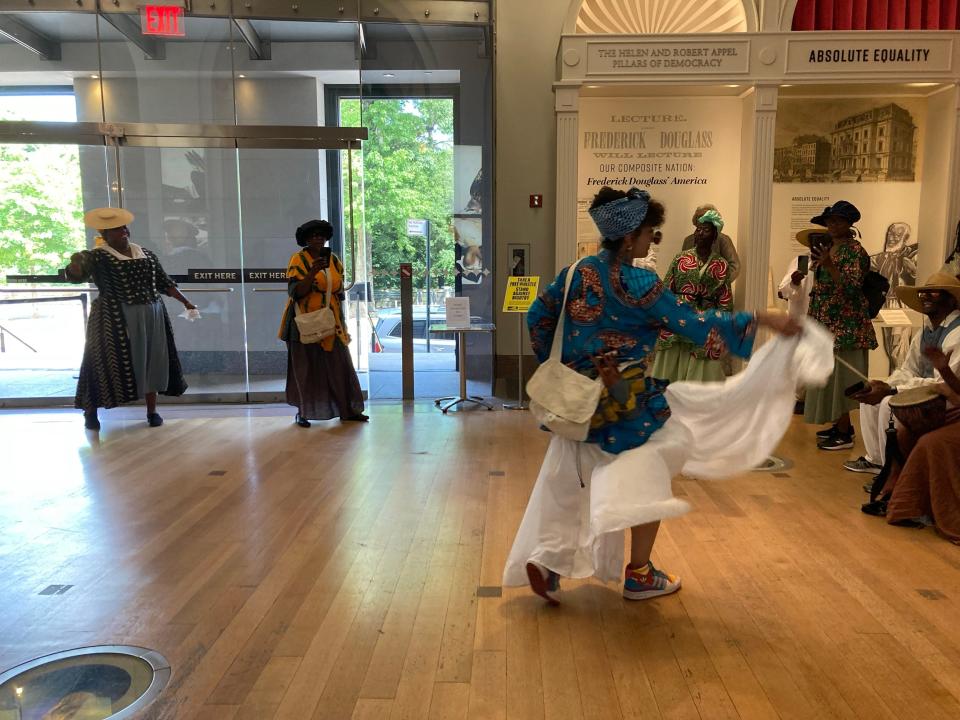

The event McKnight organized in Manhattan on May 25 began with songs and dance honoring ancestors, before the first annual stroll through town. In addition to her work with the historical society, McKnight runs Not Your Momma’s History, a website with a quarter-million followers on YouTube that offers educational videos and programming about slavery and the African experience in Colonial America and the early U.S.

The Pinkster participants walked through the Dyckman Farmhouse, a museum and former home of a Dutch family who held enslaved people. The group moved down Broadway, drumming as they traversed a Dominican business corridor. A man carting recycled cans and bottles bobbed his head to the beat, shouting, “?En Nueva York!”

Enslaved Africans arrived in New York just a few years after Dutch colonizers settled there. Thousands came in bondage from the Caribbean and Africa, often from the Kongo or Loango peoples, between the early 1600s and the late 1700s, when the slave trade ended. New York abolished slavery in 1827.

New York’s enslaved population was smaller than plantation economies in the South, however, enslavement was pervasive in the northern city. Enslaved Black New Yorkers often lived in isolation from one another, with only a few people living on farms or in homes. They worked as domestic servants, laborers, tradesmen and dock workers in New York Harbor.

In 1730, enslaved people made up about a fifth of Manhattan’s population. During the 1790 U.S. census, enslaved people accounted for about a third of Kings County, which is present-day Brooklyn. More than 60% of households had enslaved people.

Slavery was "really integral to this society,” said Andrea Mosterman, a professor of early American history at the University of New Orleans. “For more than 200 years, slavery was a regular part of New York life.”

White New Yorkers heavily restricted and surveilled enslaved people’s movements. They could not move around without travel passes. They were mandated to use lanterns at night, and prohibited from purchasing certain goods, said Mosterman, who wrote a history of slavery and resistance in Dutch New York.

In this context, Pinkster, a springtime Christian holiday, gave people a respite from bondage. Slave-owning societies often gave enslaved people a few days off, typically around Christmas or Easter. The premise was that enslaved people wouldn't rebel if they had limited freedoms, according to Myra Young Armstead, a history professor at Bard College in New York.

Enslaved African people in New York: Suburb uncovers hidden burial ground as NY studies centuries of African American history

Pinkster as resistance

Pinkster had a broader meaning for Black Americans, Armstead said: It represented resistance. Pinkster evolved into a weeklong secular gathering for enslaved people separated from their family and friends, a place to practice African traditions in community with others.

“It really does function as a way for the slaves to perform their true selves, their true identities,” said Armstead, who wrote a public history on enslavement in upstate New York. “To connect with relatives and friends that they’re prevented from seeing.”

The abolitionist Sojourner Truth, born enslaved in Dutch-speaking New York, described Pinkster celebrations with longing, she recounted in her dictated autobiography. In 1803, the Albany Centinel, a white newspaper, described seeing a “Guinea dance” and “Guinea drum” at Pinkster celebrations, and historical accounts mention a Pinkster king who presided over ceremonies, a tradition likely rooted in west-central African traditions that adopted Christianity before the slave trade, according to historian and author Jeroen Dewulf. Other accounts from the 1800s noted the festival included thousands of Black people from New York and New Jersey.

Pinkster is believed to have been the largest African American celebration in Colonial American and early U.S. history, Dewulf said in an email. Black people organized Pinkster events, but attendees were from different racial backgrounds, he added.

By the 19th century, the celebrations dwindled. One key factor in their decline was that New York state in 1811 effectively outlawed Pinkster. Armstead, from Bard, said the ban was prompted by fear among white landowners after the late-18th century Haitian Revolution, in which enslaved Black people revolted against the Caribbean island's dominant white enslaving class. White lawmakers in the U.S. took steps to prohibit Black people from gathering in groups.

The last recorded events happened in the mid-1800s, said Lavada Nahon, an author and public historian for the New York state parks office.

Rediscovering Pinkster

Reviving the tradition is deeply meaningful, Nahon said, since the holiday honors the humanity of Black people living under bondage.

“We need to take the shame that other people have placed upon us off by rediscovering things like Pinkster and celebrating them however we choose to," she told USA TODAY. “It’s vitally important that people went out of their way to remain human in their own eyes.”

About eight years ago, McKnight, at the Historical Society, saw a group of Black people donning 18th-century clothing near the famed Apollo Theater, in the heart of Harlem, the historic African American neighborhood with a Dutch name. The group members wore West African garments and had drums and a banjo. She didn't know if the group was going to a Pinkster celebration, but that moment inspired her to revive the tradition with a stroll.

In the Saturday afternoon heat, the group arrived at the New-York Historical Society, the city’s first museum founded in 1804. McKnight envisions Pinkster as a holiday for the Black diaspora, for people from the Caribbean, Latin America, the northern and southern U.S., and Africa in New York City.

“I just kind of wanted it to be a gift to, you know, Black New Yorkers,” she told USA TODAY. “It’s for them. And it's not about educating white folks or the public about us. It's about us.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What is Pinkster? An early African American holiday revived