After Iowa fiasco, New Hampshire matters more than ever

Confused about what happened Monday night in the much-hyped Iowa caucuses? You’re not alone — so are the candidates, the media, the state party, the national party and the rest of the country. But there’s hope for some clarity — if not today, then by next week, when New Hampshire Democrats will vote in what will (thankfully) be a conventional secret-ballot primary.

After a full year of stumping, spinning, sniping and speculating, the chaotic denouement of Iowa’s moment in the national political spotlight was unprecedented in every way. Three sets of results. Mobile-app snafus. “Quality checks” that endlessly delayed the data. Frustrated candidates delivering victory speeches long before an actual victor has been declared. A final call now not expected to come until “today, tomorrow, the next day, a week, a month later,” according to the chair of the Iowa Democratic Party — well after the news cycle has moved on and the window to capture Iowa’s coveted momentum has closed.

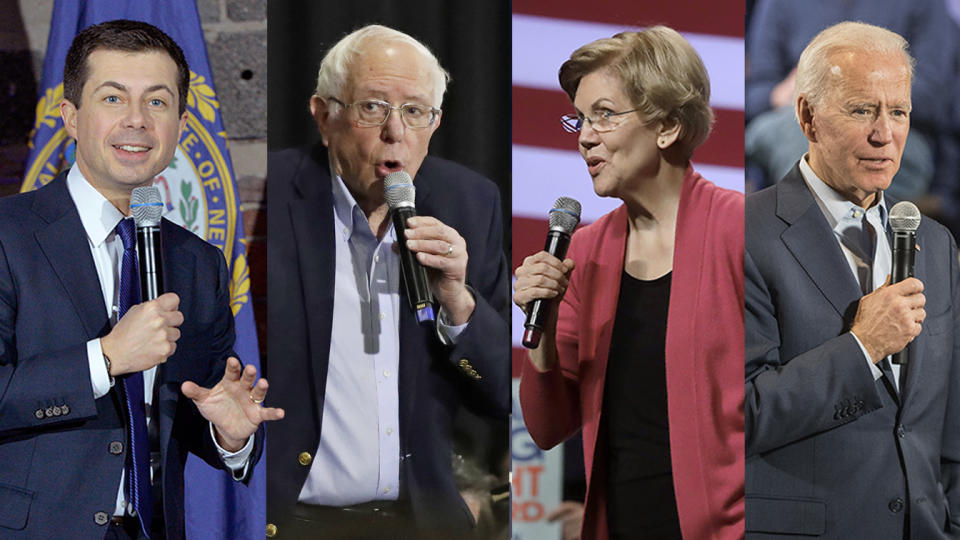

And after all that, what is shaping up to be the most evenly divided delegate haul in history, with Pete Buttigieg, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden — perhaps in that order, or any of several other permutations — all likely earning between 15 and 30 percent of the vote.

On a normal caucus night. Sanders’s strong showing, Buttigieg’s late surge and Biden’s anemic performance would have been the big news. But instead Iowa’s disastrous implosion has overshadowed and nearly nullified the results.

“Iowa is about the momentum you gain — or lose — much more than the delegates,” tweeted Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign manager, David Plouffe. “Likely the winner and the surprisingly strong showings get muted and those that did poorly do not pay the full price. It is what it is.”

Which means that what happens next could matter more than ever.

Before Iowa, Sanders was the heavy favorite to win New Hampshire. On the eve of the caucuses, the most carefully calibrated Iowa polling average (courtesy FiveThirtyEight) showed Sanders leading Biden by a mere 1.5 percentage points. In New Hampshire, however, the same site shows Sanders ahead of Biden by more than 8 points (25.2 percent to 17.1 percent) — and clobbering both Warren (13.9 percent) and Buttigieg (12.2 percent).

Last time around, Sanders, who has represented the neighboring state of Vermont in the Senate since 2007, defeated Hillary Clinton in New Hampshire by more than 22 percentage points — nearly twice his average lead in the final pre-primary polls. He did so by dominating among independents, who are expected to make up 40 percent of this year’s primary electorate. In 2016, Sanders’s margin among Democrats was 4 percentage points. His margin among independents was 48 percentage points. If it turns out he did win in Iowa, a New Hampshire victory would make him the candidate to beat going forward.

Yet New Hampshire also has a contrarian tradition of bucking expectations and boosting underdogs — and Granite State voters appear to be much more undecided than usual. According to a recent survey by the University of New Hampshire, half the electorate there still hasn’t chosen a horse; another 20 percent say they’re leaning one way but could still change their minds. The mess in Iowa is unlikely to have its usual effect of narrowing New Hampshire’s options and reducing such indecision.

Two candidates in particular may be best positioned to capitalize on this odd dynamic: Biden and Buttigieg. They’d each be following in the footsteps of a different Clinton.

In 1992, the young, previously little-known moderate Bill Clinton, damaged by reports of extramarital affairs, fell behind in the New Hampshire polls — then pulled off a surprise second-place finish after appearing with his wife, Hillary, on “60 Minutes” to rebuff the charges. Clinton called himself “the Comeback Kid,” and the rest is history.

A first- or even second-place finish from Buttigieg in New Hampshire might be seen in a similar light: as a kind of comeback after the Iowa debacle, and a further validation of his candidacy. If Buttigieg (who raised more money in New Hampshire in 2019 than any of his rivals) beats Biden twice in a row, it will bolster his claim to be the more electable moderate alternative to Sanders — a good position to be in heading into states such as Nevada, South Carolina and California, where Buttigieg has struggled to attract support from voters of color.

It’s also possible that Biden could be the new Hillary. After losing to Obama in Iowa in 2008, Clinton — the longtime frontrunner and establishment favorite — looked certain to lose in New Hampshire as well; some polls showed her trailing by double-digit margins. But when a voter in Portsmouth asked, “How did you get out the door every day? I mean, as a woman,” Clinton teared up. “This is very personal for me,” the candidate replied. “Not just political.” That rare tender moment redirected the narrative, and New Hampshire voters gave Clinton a second chance. On primary night, she defeated Obama by 2.6 percentage points. Is Biden New Hampshire’s latest establishment underdog?

Time will tell, as the pundits like to say. For now, we know that Iowa has not winnowed the sprawling field, which is another unprecedented side effect of Monday’s fiasco. Warren, who represents the neighboring state of Massachusetts, has a significant presence in New Hampshire, and her team flew in Tuesday for a morning town hall in Keene, claiming Iowa was a “very close race among the top three candidates (Warren, Sanders, Buttigieg)” with Biden “a distant fourth.” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who likely finished a disappointing fifth in Iowa, arrived Tuesday for events in Concord, Portsmouth and Nashua, touting endorsements from top members of the New Hampshire Legislature as well as the editorial boards of the state’s three biggest newspapers. Andrew Yang is holding town halls Tuesday in New London, Laconia and Lebanon; Biden is hosting community events in Nashua and Concord; Buttigieg has five “Meet Pete” gatherings on his schedule. Michael Bennet, Tulsi Gabbard and Deval Patrick are campaigning in New Hampshire as well.

And then there’s Mike Bloomberg to consider. The multibillionaire former New York mayor isn’t competing in New Hampshire, but he has spent hundreds of millions of dollars positioning himself for March’s delegate-rich primaries, starting with Super Tuesday. He has passed Buttigieg for fourth place in the national polls, with the latest surveys showing him above 10 percent. And the better Sanders performs in places like Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada (where he’s tied for first) and California (where he leads by 5 points), the better Bloomberg’s chances of eventually emerging as the establishment’s 11th-hour white knight — which is likely why, after Iowa, Bloomberg leapfrogged Biden for the nomination on the betting site Predictit.

It’s also why on Tuesday, Bloomberg authorized his campaign to double its ad spending and expand its staff to 2,000 people.

Never before has Iowa ever delivered so muddled a verdict — let alone in a manner so disorganized that it’s already triggering calls to strip the Hawkeye State of its treasured first-in-the-nation status.

But the truth is, Iowa is no stranger to fraught caucus outcomes. In 1976, “uncommitted” defeated Jimmy Carter. In 1988, Paul Simon and Dick Gephardt were still deadlocked at bedtime. In 2012, Mitt Romney seemed to have edged out Rick Santorum on caucus night — until Santorum was named the winner three weeks later. And in 2016, runner-up Bernie Sanders claimed he’d earned more raw votes than Hillary Clinton, who didn’t release her victory statement until the wee hours of the morning.

Which is where New Hampshire traditionally comes in.

Look at a list of previous Iowa winners and you’ll notice a number of campaigns that never went anywhere: Santorum, Gephardt, Mike Huckabee, Tom Harkin.

But the one-two punch of Iowa and New Hampshire has been far more predictive. In fact, since the start of the modern primary era in 1976, every candidate who has won both states has also gone on to win his party’s nomination. Only one nominee — Bill Clinton — won neither. In competitive races, New Hampshire Democrats have picked their party’s eventual nominee on five separate occasions: Carter (twice), Michael Dukakis in 1988, Al Gore in 2000 and John Kerry in 2004. New Hampshire Republicans, meanwhile, have done it six times: Gerald Ford in 1976, Ronald Reagan in 1980, George H.W. Bush in 1988, John McCain in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016.

The question now is who New Hampshire will elevate next — a decision that may weigh even more heavily on this primary contest than it has in the past.

Read more from Yahoo News: