After Trump speaks on criminal justice reform, Dem candidates will push their own plans. Here's what they're discussing.

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

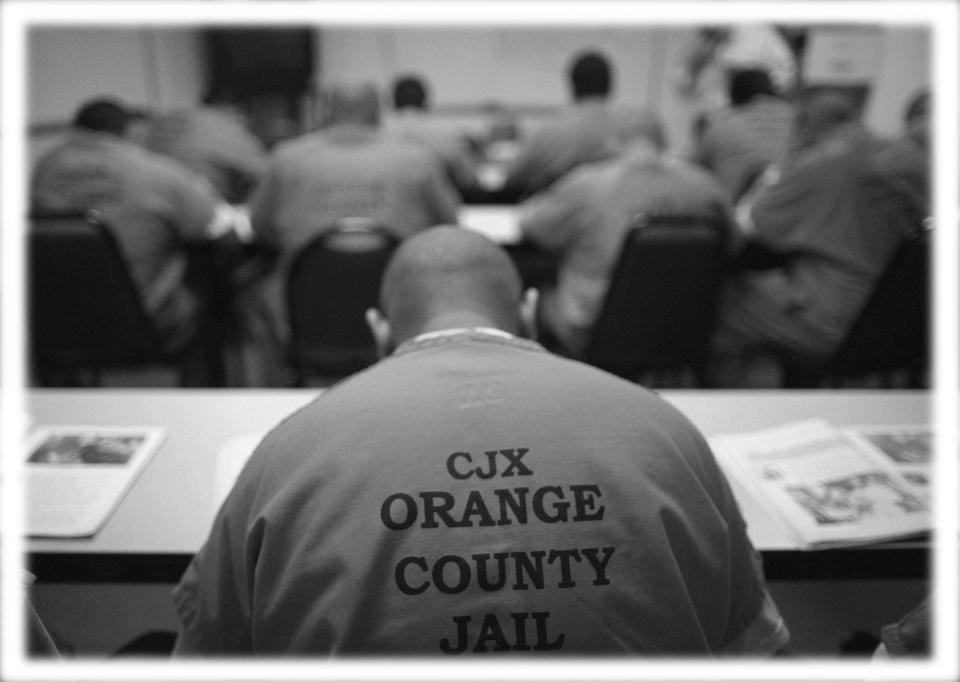

The United States, the richest country in the world, also incarcerates more people than any other nation, almost 2.2 million as of the end of 2016. But the criminal justice system touches many more people than the number actually behind bars at any one time. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, “over 600,000 people enter prison gates, but people go to jail 10.6 million times” annually, and nearly half a million people are “locked up on nonviolent drug offenses on any given day.”

And the effect of a prison sentence can last a lifetime.

In the summer of 1996, Daryl Atkinson began a 10-year prison sentence at the Alabama Department of Corrections for drug trafficking. “When I was released from incarceration, that was only the beginning of the punishment,” Atkinson, who served a mandatory minimum of 40 months on his sentence, told Yahoo News in an interview. “My driver’s license was automatically suspended because of my drug crime. I was denied federal financial student aid because of my drug crime. I was given an over $60,000 civil fine that I still have to pay back because of my drug crime. I couldn’t and still can’t vote in the state of Alabama because of my drug crime. I was denied admittance to several undergraduate schools and law schools because of my drug crime.”

These “collateral consequences,” as Atkinson referred to them, make it difficult to reenter society and more likely that an ex-convict will return to crime.

“Fortunate enough for me, I returned home to a loving family that could provide me food, clothing and shelter,” said Atkinson, now the executive director of Forward Justice, a law and policy advocacy group dedicated to civil rights, racial justice, and social and economic change.

“I went into prison with a high school diploma. I came out with a high school diploma. But I had that stability as far as a family system to return to. I was able to work out a plan. And I went back and I got my associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree and a law degree.”

But many former prisoners aren’t so lucky.

Public and political discourse on criminal justice has shifted dramatically in recent decades across the political spectrum.

The Constitution established protections for individuals in their interaction with three elements of the criminal justice system: law enforcement, courts and corrections. The Fourth through Eighth amendments established procedures for arrests, grand jury indictments, arraignments and trial.

They remain the basis of a criminal justice system that many nations have sought to copy, and remain, in principle, as fair as any in the world.

But the system was not always fair to the disadvantaged or oppressed. It wasn’t until 1963, in Gideon v. Wainwright, that the U.S. Supreme Court would rule that states under the Sixth Amendment were required to provide an attorney to defendants in criminal cases who are unable to afford their own attorneys.

Then, amid rising crime, a drug epidemic and fears about public safety in the 1980s, changes in the law led to more pretrial detention for suspects, mandatory minimum sentences, an increase in the use of solitary confinement to punish and control inmates — and an explosion of prison populations.

The Bail Reform Act of 1984 changed the practice, mandated by Congress in 1966, of releasing suspects on their own recognizance if their appearance for trial was assured. It allowed a judge in a federal court to detain suspects as potential flight risks or if considered a serious threat to public safety. Many states followed suit, adopting similar statutes. In 2016, 450,000 people were locked up without a conviction or sentencing, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

By the time the crack epidemic began to ravage African-American communities, “law and order” had become a popular rhetoric among conservative politicians. President Ronald Reagan’s “tough on crime” stance merged with the “war on drugs,” resulting in harsh penalties for drug offenses.

“When Reagan took office in 1980, the total prison population was 329,000, and when he left office eight years later, the prison population had essentially doubled, to 627,000. This staggering rise in incarceration hit communities of color the hardest,” the Brennan Center for Justice points out.

But Republicans weren’t alone in their crusade against crime. Democrats, afraid of being labeled “soft on crime,” also supported legislation such as the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which was signed by Reagan and introduced mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses.

Infamously, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, a bipartisan crime bill that then-Sen. Joe BIden helped write, stiffened penalties for drug crimes, especially those involving crack cocaine. The law has been blamed for putting hundreds of thousands of black men in prison. It wouldn't be until after 2010, when Barack Obama's administration passed the Fair Sentencing Act to reduce the disparity in sentences between crack (most prevalent in minority communities) and powder cocaine (more commonly used by whites), that the number of federal prosecutions of offenders decreased by half.

But even before America elected its first black president, public attitudes toward crime and punishment had begun to change. “Increasingly, Republicans are talking about helping ex-prisoners find housing, drug treatment, mental-health counseling, job training and education,” reported the New York Times in 2006.

“The nation’s incarceration rate peaked at 1,000 inmates per 100,000 adults during the three-year period between 2006 and 2008,” according to the Pew Research Center.

In his final year in office, President George W. Bush signed the Second Chance Act, allocating $362 million to prisons for various reentry programs, to “help give prisoners across America a second chance for a better life,” he said before the signing.

The legislation paved the way for President Trump’s First Step Act, which Congress passed last December, reauthorizing and building on the Second Chance Act. It aims to reduce recidivism, shorten mandatory minimum sentences for some drug offenses, and support people currently in the criminal justice system. Over 3,100 people were released from federal prison as parts of the First Step Act went into effect. But the law benefits only a fraction of imprisoned people, since most of them aren’t held in federal prisons, where nearly half of all inmates are locked up for drug charges, but held in state prisons and local jails. Additionally, those convicted of violent crimes and abortion-related offenses are ineligible for early release programs under the law, along with 11,000 prisoners convicted of violating immigration laws.

The past few years have seen additional progress for reform advocates, including the election of progressive prosecutors, an overhaul of cash bail for suspects awaiting trial and voting rights restoration to ex-felons. The prison population has been steadily, if slowly, declining from its peak in 2009, according to a recent Bureau of Justice Statistics report. And the disparity between African-Americans and whites in prison is shrinking.

Democratic candidates are now capitalizing on the rare bipartisan support on Capitol HIll and in the White House to propose major structural reform to the U.S. criminal justice system.

Democratic contenders, who along with Trump head to South Carolina this weekend for a criminal justice forum at the historically black Benedict College, have been touting ambitious plans that aim to end laws and practices that they say contribute to mass incarceration and threaten public safety.

In recent months, they have proposed big ideas — releasing prisoners who’ve faced harsh sentencing, decriminalizing or legalizing marijuana, banning for-profit prisons and improving police-community relations, eliminating solitary confinement and capital punishment, ending money bail and mandatory minimum sentences, and restoring rights, including voting, to released inmates.

The leading progressives in the race unveiled comprehensive criminal justice proposals at about the same time in August. Bernie Sanders’s plan includes all of the above points and an overall rethinking of criminal justice. His plan approaches disparities in the criminal justice system by addressing underlying societal issues that contribute to crime such as mental illness, addiction, underfunded schools, homelessness or poverty.

“We must move away from an overly punitive approach to public safety and start focusing on how to safeguard our communities, prevent the conditions that lead to arrests, and rehabilitate people who have made mistakes,” he wrote.

Days after Sanders put forth his plan, Elizabeth Warren released her own comprehensive criminal justice proposal, saying “real reform requires examining every step of this system.”

“We cannot achieve this by nibbling around the edges — we need to tackle the problem at its roots. That means implementing a set of bold, structural changes at all levels of government.”

Warren called for increased law enforcement oversight, improved resources for public defenders and holding prosecutors accountable for abuses, all elements Sanders addresses. She also called for repealing the 1994 crime bill.

Biden has also unveiled a plan to remedy the negative impacts of the bill he helped pass, as a part of his decarceration initiative, which includes ending cash bail and addressing racial disparities in education spending, policing and sentencing.

As a senator, Cory Booker has championed criminal justice reform and has a long history of crafting and supporting bills that aim to reverse mass incarceration.

Earlier this year, he introduced a Senate version of the Second Look Act of 2019, building on Trump’s First Step Act to give more federal prisoners a chance at early release. The legislation would allow federal judges to consider petitions for sentence reduction after a person has served at least 10 years and is considered not to be a danger to public safety, regardless of the crime.

Booker has also proposed using the president’s clemency power to bypass Congress and provide early release to as many as tens of thousands of federal inmates serving excessive sentences.

His aggressive proposals call for scaling back mass incarceration, ending the war on drugs and, similar to Sanders, reinstating the right for formerly incarcerated individuals to vote in federal elections. Booker’s stance on criminal justice reform has helped overcome doubts about his record as mayor of Newark, N.J., when he supported police “stop and frisk” tactics that targeted African-Americans.

The same hasn’t been said for Sen. Kamala Harris, whose record as California’s top cop continues to bring her under scrutiny from the progressive Democratic base.

Harris, the self-proclaimed “progressive prosecutor,” “pushed for higher cash bails for certain crimes in 2004 as San Francisco’s district attorney, declined to support marijuana legalization in 2010 and, as California’s attorney general, refused to back independent investigations for police shootings as recently as 2014,” said the New York Times.

But as the Times reported, she backs a plan to “fundamentally transform our criminal justice system.”

“I was swimming against the current, and thankfully the currents have changed,” she told the Times in defense of her new public stance on criminal justice reform. “The winds are in our sails. And I’m riding that just like everybody else is — because it’s long overdue.”

The plan, which was crafted with the help of racial and social justice advocates, including black progressives who have criticized her record, mirrors the plans of Booker, Sanders and Warren in that it centers around disrupting a system that profits from a prison population, tackles social issues that lead to incarceration and ensures prisoners are treated humanely during and after their time served. But her plan also aims to create a national police systems review board and establish a National Criminal Justice Commission to study criminal justice systems and provide recommendations on major structural reforms.

While there was a point when Democrats were hesitant to rally against the criminal justice system in fear of being considered “soft on crime,” today’s political climate has a platform for ideas promoting big, structural reform.

Increasingly, research has unearthed inequities embedded in how America addresses issues of crime and punishment. Public opinion has followed. Polls have found that a majority of Americans, around 91 percent in 2017, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, support criminal justice reform.

“The conversation today is unrecognizable from where it was just 10 years ago, let alone 30,” Adam Gelb, president of the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan research organization, told Yahoo News. “What we have now is candidates competing to see who can be the most aggressively progressive, rather than who can thump their chest the loudest.”

“There used to be almost an article of faith that to drive crime down, prisons had to go up,” he continued, “and starting about 10 years ago now, people started to see that it was possible to reduce crime and imprisonment at the same time.”

Still, Gelb pointed out that crime is not a priority issue among voters.

“Crime isn’t the dominant issue that it was in the early ’90s, and so there’s a lot less pressure on political leaders to offer headline-grabbing solutions,” he said, adding that “it’s not a top tier issue for the general public, but it is a top priority for a very vocal group of activists in the [Democratic] Party.”

Therefore, “the thrust of most of the proposals is to undo what are viewed as many of the excesses of criminal justice policy over the past quarter century,” said Gelb. The far-reaching plans that focus on underlying issues like improving health care and education could have an effect on crime and incarceration rates, he acknowledged, but only over the long term, while “strategies in policing, pretrial detention and sentencing and reentry can have substantial impact now. We can’t overlook those in favor of longer-term societal restructuring.”

But as a formerly incarcerated American, Atkinson believes the best approach to fixing the criminal justice system is a “very holistic” one.

“Criminal justice reform has in some ways become en vogue,” he said, challenging “Democrats who want to curry people’s vote and particularly communities of color” to consider all the ways in which millions of Americans interact with the criminal justice system before they put forth “policy prescriptions.”

“The 2.2 million people who are in a cage, the other 5 million folks that are on probation or parole and the over 70 million Americans in this country — one in three adults that have a criminal record or a criminal background in some kind of database — all of these people have families, many of them are voters, many of them are actively civically engaged. And as a result, candidates need to be responsive to that constituent base,” Atkinson said.

Michael Tanner, a senior fellow at the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, told Yahoo News that across the board politically, approaches to criminal justice have changed not only “because crime is down, the public doesn’t feel like everybody needs to run for sheriff anymore,” but also in part due to race.

“African-Americans are a key constituency,” Tanner told Yahoo News. “And one way to appeal to that constituency has been on the criminal justice reform issue, so you’re seeing even Kamala Harris, who was as strict a prosecutor as you could ever find in California, now suddenly championing criminal justice reform issues.”

Considering that African-Americans make up about 12 percent of the U.S. population but 33 percent of the federal and state prison population, according to the Pew Research Center, proposals from Democratic candidates demonstrate the party’s commitment to black voters.

As for Republicans, Tanner argues that on a state level, GOP governors like Rick Perry of Texas championed criminal justice issues in part because of cost.

“Prisons are expensive,” he said, adding that Republican leaders may have seen criminal justice reform “as a way to reach out to minority constituencies that didn’t involve money.”

Tanner added: “Then there’s just a reaction generally to government overreach. If you’re kind of against big government and you don’t trust the government, the criminal justice system is an obvious target.”

As with many policy proposals by Democratic candidates, criminal justice reform platforms are aspirational, and the next president will be limited in what he or she can accomplish. Most criminal justice issues are at the state or local level, and any changes to the law have to go through Congress.

“Not only do these candidates need to get elected, but Congress also has to break down in the right way so that they can get a veto-proof majority, which is essentially what they’re likely going to need to sort of push some of the proposals,” said Rafael Mangual, a fellow and deputy director of legal policy at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research and a proponent for prioritizing public safety within criminal justice reform. “While federal reforms may help move the needle a bit at the margins, the reality is that criminal justice is and always will be a state-based endeavor. The vast majority of prisoners are held at the state level, where the vast majority of enforcement happens.”

Mangual perceives the leftward shift in the debate around the criminal justice system as a result of a “false narrative” that “basically states that the U.S. can actually be described as a draconian carceral state in which millions of people are wrongfully in prison for low-level and nonviolent offenses for long stretches of time.”

“You start to feel invincible the further removed from a crime epidemic that you get,” he said. “And sometimes some of the lessons that were learned in fighting that crime get lost.”

Mangual expressed concerns that vulnerable, low-income minority communities will face increased crime in light of ambitious decarceration plans, not communities made up of white, high-income citizens. He advises that candidates approach their reform proposals with caution to make sure “we’re doing things incrementally so that we get it right.”

“Because real people are going to have to pay the price for these things,” he said. “And that price is not going to be borne equally by people across the country. It is going to be disproportionately borne by people living in communities that are already vulnerable and likely already suffering from violent crime problems.”

But Atkinson argued that the “conversation around safety is always absent the people in communities who experience crime in violence at the highest levels.”

“When we think about safety, we usually think about police, prosecution, probation. But when you look at the communities that produce the lowest indexes of rapes, robberies, murders per capita in the country, those communities have green space. They have thriving schools and economic opportunity and housing.”

In contrast, he said, “When you look at the least advantaged communities, the communities that produce the highest index with the rapes, robberies, homicides, those communities only have a police presence. They only have a prosecutorial presence. They don’t have thriving schools and economic opportunity and safe and affordable housing — those other social economic indicators of health that produce safety.”

Cover thumbnail photo: Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren and Cory Booker. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP, Getty Images, AP [2], Getty Images, AP)

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: