'Those most alone': The street children of Melilla, risking all to get to Spain

After crossing 130 miles on ferry from southern Spain to the tiny Spanish enclave of Melilla, a finger of Africa curling into the Mediterranean, travelers are greeted with the sight of a 16th century fortress, whose stone ramparts overlook a steep cliff.

Hiding along the cliffs and in woods, runaway children are watching the ferry as it docks, and the line of trucks waiting to board it for the return voyage to Spain, seeing them as their tickets to riches.

Held by the Spanish since 1495, Melilla, a small port city once famous for its bustling trade in beeswax and goat skins, shares a seven-mile border with Morocco, defended by a 20-foot-high triple-reinforced fence threaded with barbed wire and topped with blades. It’s meant to keep out migrants from sub-Saharan countries who don’t have passports to enter legally. Despite mesh so fine that fingers can’t grab hold of it, thousands of foreigners successfully scale the barrier annually, using hooks to hoist themselves up and jump across it, though many are injured in the process.

Moroccans can enter legally, and tens of thousands do each day through the one pedestrian control point along the border. Most are workers and shoppers who return at day’s end, but some are hoping to make their way from Melilla to the European continent. Among those entering alone, and not leaving, are boys as young as 8, many of whom make the trip with their parents’ blessing.

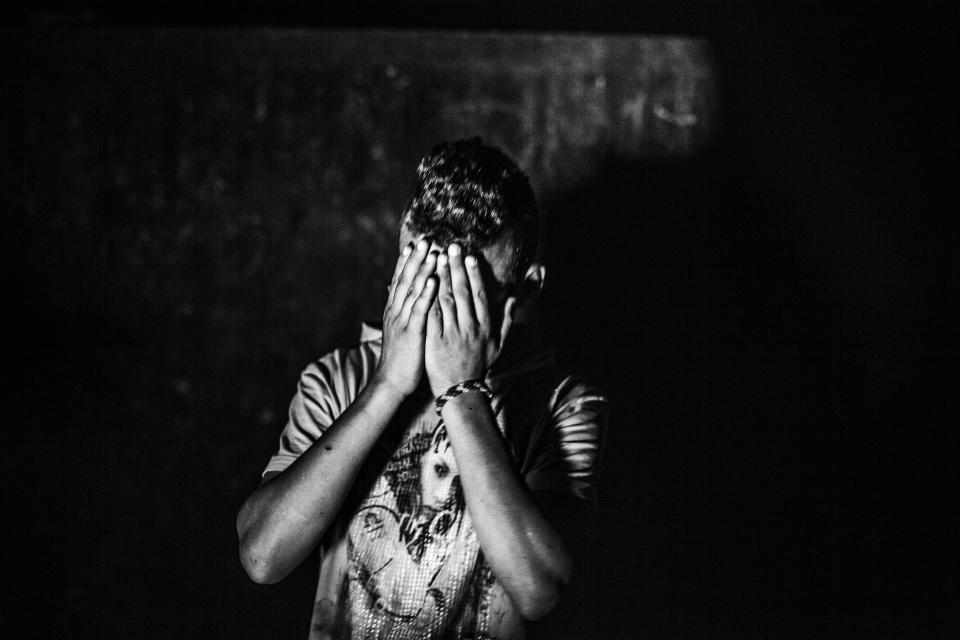

“They want to go to work and help their family, especially their mother and siblings in Morocco,” says Spanish photojournalist José Colón, who for the past 15 years has been photographing street kids in Melilla and Ceuta, another Spanish enclave 250 miles away, across from Gibraltar. Some, he says, “want to be footballers” — playing for famous soccer teams.

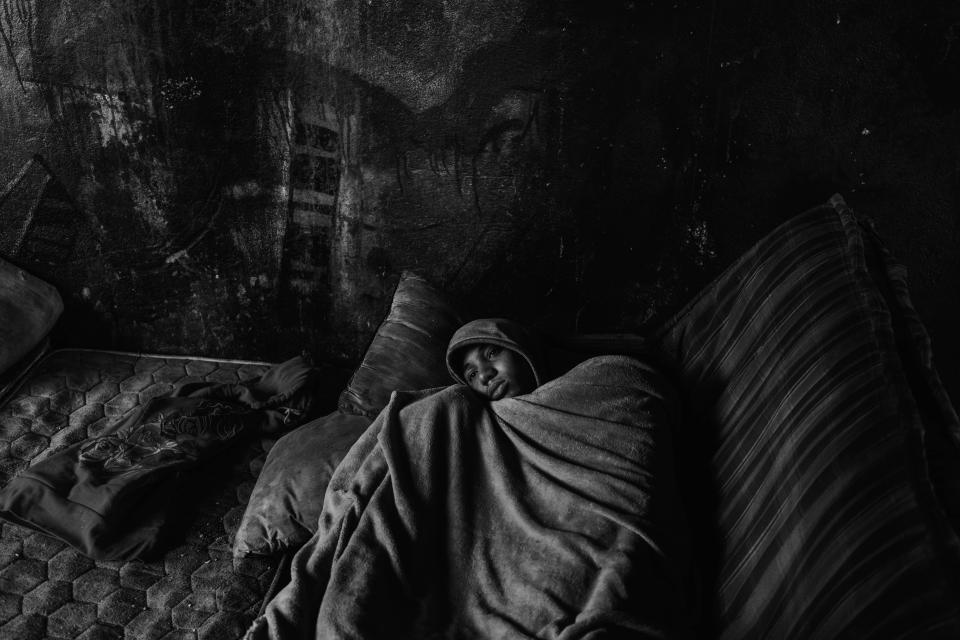

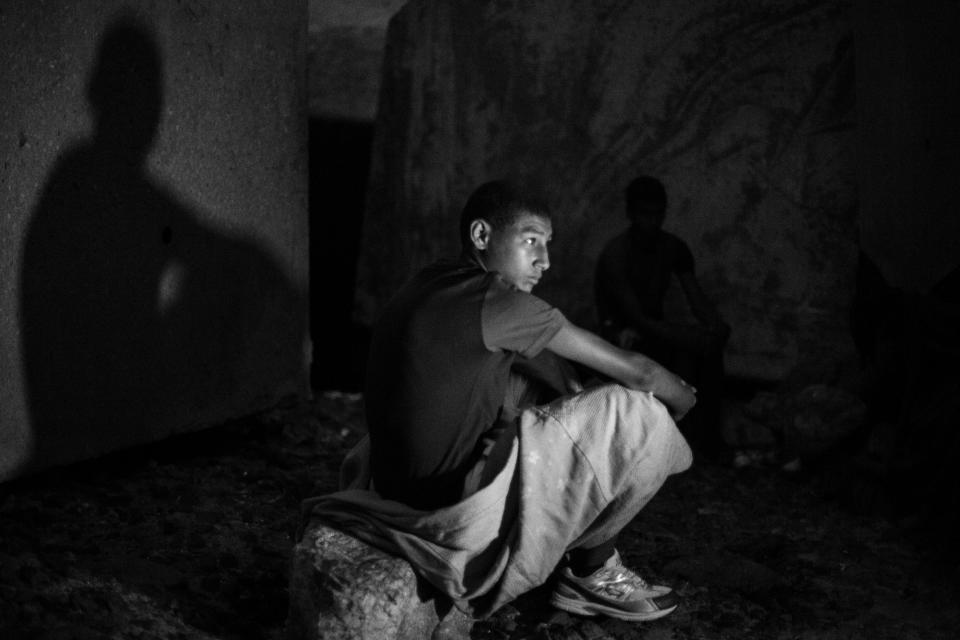

And hundreds of these kids are camping on concrete slabs along the docks at night, under bridges or in nearby caves: Street kids are hiding out in abandoned cars, even sleeping in trash cans and foraging through dumpsters and the municipal dump to survive and make good on their dream of a better life on the mainland.

According to Save the Children, last year more than a thousand unaccompanied foreign minors, mostly from Morocco, arrived in Melilla and Ceuta. By law, as unaccompanied foreign minors — known as menas — these kids can’t be returned to Morocco once they’ve entered these Spanish territories in Africa. Instead, when discovered, they’re locked up in overcrowded juvenile centers, such as La Purísima, that NGO groups criticize as being substandard and rife with maltreatment and violence; last week, a teacher there was arrested for stabbing a pupil. Many of the students escape to live in the streets.

But life on their own is more dangerous — and not only because they’re dealing with the basics of survival and always hiding from the police. It’s because they do “the risky” as they call their only hope of getting to the mainland by stowing away on a ferry for the five-hour trip across the Mediterranean to the Spain. The usual way to do this is to crawl under ferry-bound trucks and hide between the axles. Sometimes they get trapped; recently one teen traveled on the underside of a tour bus for 160 miles in blazing heat before passengers heard his cries. Other have been fatally run over while attempting the maneuver.

Truck drivers are now wise to their ploys: At the sight of the boys, they floor it. Thus even finding a vehicle for clandestine transport onto ferries may take weeks, months, sometimes years of trying while camping out in Melilla, where human traffickers are reportedly now on the prowl for the street kids, sometimes getting them addicted to sniffing glue in hopes of taking control of their lives.

Upon the ferries’ arrival back in southern Spain, police search arriving vehicles with dogs, and migrants they discover are sent back to Melilla. Nevertheless, it’s estimated that some 10 percent of the 20,000 illegal migrants, including adults, who attempt to leave Melilla and Ceuta do eventually make it to mainland Spain; they’re aboard nearly every ferry that leaves. Last year, when a ferry crashed into the port in Malaga, police discovered that of the 150 on board, seven were stowaways.

And the number of kids entering Spain by themselves — whether by hiding on ferries or trying to cross the Mediterranean from Libya in flimsy vessels — is increasing. According to Save the Children in its report “Los Más Solos” (Those Most Alone), 6,414 unaccompanied foreign minors showed up there in 2017 — a 60 percent jump over the nearly 4,000 who arrived in 2016.

Some stay near where they arrive, but many head north — to Madrid and Barcelona, seeking work. And if they can’t find it, many of these kids — who, according to photographer Colón, largely avoid crime while in Melilla — may end up in the infamous brigades of purse snatchers who target unsuspecting tourists. And, if caught, they may be deported and start the risky cycle all over again in Melilla, where the official government motto speaks a grim truth: “Non Plus Ultra” — Latin for “Nothing More beyond.”

The work of award winning photojournalist José Colón has been shown in Spain, Italy, USA, Germany, France and Brazil as well as in various international magazines. He has artistically collaborated with the Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, the Museum of History of Barcelona and the Museum of History of Zaragoza. He is currently based between Barcelona and Seville, where he works with several international newspapers and photo agencies.

Melissa Rossi, a writer based in Barcelona, is the author of the geopolitical book series “What Every American Should Know.” (Plume/Penguin).

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: