Americans shared a powerful moment during 2024 solar eclipse. This is what they saw.

EAGLE PASS, Texas – It was noon, and the cloud cover had been looming all morning. Alejandra Martinez, a seventh-grade science teacher from this city in south Texas, peered up at the gauzy gray sky.

She was sitting at the corner of the county airport just outside Eagle Pass, just a couple of miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. Beside her stood a special telescope for a citizen-driven NASA science project to capture views of the sun during the eclipse – if they could see it.

“We’re going to stay positive,” Martinez said, turning to the team gathered around the scope. “The sun will come out, eventually.”

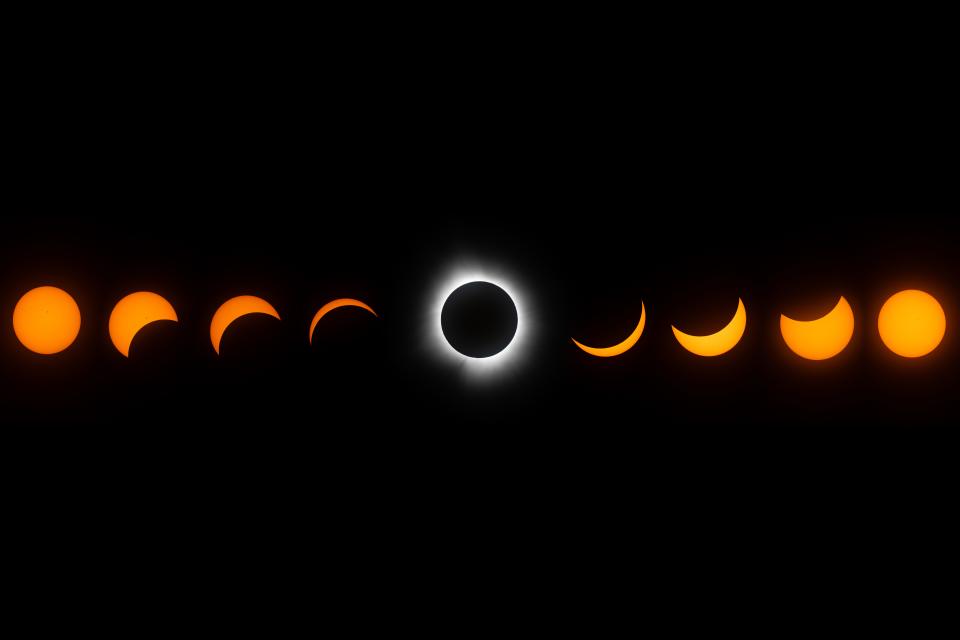

In just a few moments, the orb of the moon was set to cross the face of the sun – the rare phenomenon that has captivated human observers since the dawn of time: a total solar eclipse.

That celestial alignment would be both precisely predictable and undeniably mysterious.

Over the course of several hours, millions of people would fall beneath the moon’s shadow as it swept across the continent at some 1,500 mph. At the center of that path, however briefly, the midday sun would vanish entirely – the period of an eclipse known as “totality.”

The arc of the event was plotted by astronomers years in advance. It would begin over the blue depths of the tropical Pacific and end on the gray swells of the North Atlantic. The longest moments of totality would arrive in western Mexico.

Far more of the route, though, stretched from the flats of the Rio Grande Valley to the woods of northern Maine. Gauged by shared experience, this solar eclipse would be almost singularly American.

And that American eclipse would begin right here, for a small crowd at a small airport in a small town in south Texas, at 10 minutes past noon local time. If only the clouds would part.

Then, as if guided by some cosmic schedule, they did.

Martinez – dressed in a T-shirt that proclaimed “This Totality Rocks” – donned her dark eclipse glasses and peered upward. The haze in Eagle Pass had cleared and now, degree by imperceptible degree, the disc of the sun began to shift to a crescent.

“There it is! There it is!” she yelled. “First contact. It’s begun!”

Graphics: How the solar eclipse crossed the US

Chasing mysteries of science

At age 41, Martinez already has pursued research around the world. She has been aboard a deep-sea drilling ship in the Indian Ocean as it tried to poke into the earth’s mantle. She studied climate change’s impact on plants in the Arctic. She photographed the night sky aboard a ship in the Atlantic with the man who found the wreckage of the Titanic.

But few of those things compared to the hushed darkness that fell across Maverick County International Airport.

Last year, when Martinez heard NASA was looking for volunteers to help with the effort known as Citizen CATE 2024 (the Continental-America Telescope Eclipse), she jumped at the chance. Her team was one of more than 30 recruited by NASA to capture and record the eclipse.

She had been eagerly awaiting the eclipse that would pass directly over her hometown. Eagle Pass, the backdrop for months of a standoff between state and federal officials over the treatment of asylum seekers, could use the positive headlines, she said.

“We’ve been in the news for so much bad stuff lately,” Martinez said. “It’s super cool I get to share this with my students and get them excited about science.”

She and other scientists practiced for months leading up to the event, learning how to focus the three-foot refractor telescope and bracing for challenges, such as a malfunctioning lens, or cumulus clouds blocking their view.

As word spread that the airport was near the middle of the path of totality, other people began to plan their own arrivals.

They came from across the U.S. and as far away as Canada, Germany and Norway. Some chartered buses or drove rental cars halfway across the country. Others flew in on small planes, camping overnight on the airport’s tarmac.

Brandon Beck, 43, arrived from San Diego aboard his friend’s single-prop four-seater.

“We’re so lucky to be on a planet where the sun is the perfect size and perfect distance to create that effect,” he said. “It’s obligatory. We have to see it.” He spent the night in a sleeping bag next to the plane – built by the aircraft manufacturer Mooney.

Matt Lucas, 59, drove a rented car from San Diego to the Eagle Pass airport, hoping to replicate the solar eclipse experience he had in Cabo San Lucas in 1991. Eclipses, he said, remind us of our place in a larger world.

“In the scale of the universe, we’re here for milliseconds,” said Lucas, wearing a “United Federation of Planets” T-shirt, a nod to the Star Trek television series. “There’s more that binds us together than divides us.”

As the partial eclipse grew darker, Martinez pointed the telescope with a solar filter toward the sky.

“Amazing,” she said. “We’re all going to have this in common for the rest of our lives.”

About 1:27 p.m., the sky shifted from gray to brown. Then darkness draped the airport grounds. The sun was blotted out by the moon.

Martinez peered up through paper glasses, a hand over her heart. Tears welled in her eyes.

Life's moments of joy: Babies born and couples tie the knot during total eclipse of 2024

Into the path of totality

As the two orbs – one light, one shadow – passed each other in time and space, the shapes and colors shifted along the path below.

Eyes turned upward both inside and outside the path of totality, from ranches in the Texas hill country and blankets spread out in Washington on the National Mall.

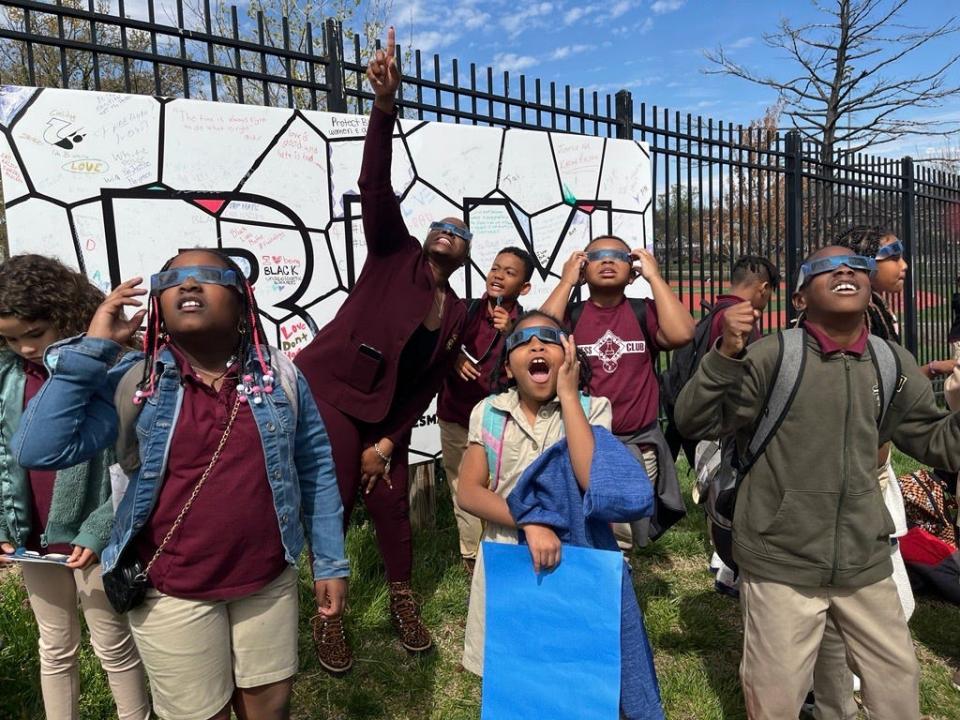

Dozens of students spilled out of Ida B. Wells Middle School in Washington, D.C., gripping cardboard solar eclipse glasses and chatting with excitement. “Why is the sun shaped as a moon?” one student asked after looking toward the sun. “Why is it not getting dark?’’ asked another.

Teacher Troy Mangum, who the students called “Mr. Mango,’’ slowly explained the science behind the experience as he cautioned others to put on their glasses. Steps away at Whittier Elementary School, younger students put on their glasses and tilted their heads up toward the sun behind their school.

Off the coast of Mazatlan, Mexico, chartered ships of various sizes carried eclipse-chasers along the seas. Whereas landlocked observers could only travel where roads would take them, ship captains faced no such constraints.

Passengers aboard Holland America's Koningsdam cruise gathered on the top decks at 10 a.m. local time. The crew, guided by an astronomer onboard, was set to adjust the ship's position meticulously to ensure the best possible view.

Mexico had become the go-to spot for the eclipse’s most dedicated chasers, some of whom have witnessed dozens of events around the globe. Each moment of totality was a notch in a lifetime scorecard, another moment in that otherworldly shadow that provokes strong reactions among so many who see it.

“I've seen people cry,” said Paul Maley, a few weeks before the moment – at 76 years old and 30 total eclipses viewed, he is one of America’s most accomplished umbraphiles. “I’ve seen them scream. I’ve seen them run around and just make wild exclamations.” Maley organized two trips to Mexico so more viewers could do the same.

Throughout history, those strange reactions have built both myths and memories among humanity. Various cultures imagined the sun was being devoured by a celestial animal, or that the darkness was an omen of doom. But not always. Historians say one recorded eclipse prompted an end to combat during an ancient Greek war. Some aboriginal cultures saw the eclipse as an amorous encounter between the sun and the moon.

Modern times brought modern scenes. Outside Little Rock and Cincinnati, couples gathered Monday to marry in mass ceremonies as the eclipse turned wedding day to wedding night.

In Indianapolis, crowds filled the famous motor speedway for a viewing event, and the freeways outside as well. State police warned that interstate rest stops were at or near capacity, and would be shut down once full, for the duration of the eclipse.

In Carbondale, Illinois, officials at Southern Illinois University were joined by teams from NASA and Chicago's Adler Planetarium for an event that would host thousands. NASA would send up a pair of balloons to study the sun’s corona. Below, on the field of the university’s Saluki Stadium, a dance troupe performed between end zones painted deep maroon. The music: The 5th Dimension’s “Let the Sunshine In.”

In Evansville, Indiana, Amber and Cody Stallings had driven all the way from Atlanta with their infant daughter, Sadie. Amber said she had seen the 2017 eclipse, but nothing compared to what they saw on the banks of the Ohio River.

“It’s breathtaking and moving,” she said. “It brought tears to my eyes.”

Sadie was strapped in a stroller as her parents shielded her eyes from the spectacle. She won’t remember it, they said, but at least she can say she was here.

The young family had already prepared themselves for the 400-mile drive home. Were they worried about the traffic? “Come on,” Amber scoffed. “We’re from Atlanta.”

Just after 3 p.m. local time, the total eclipse crossed a hayfield about 10 miles north of the small town of Spencer, Indiana, where dozens camped overnight near a tiny fishing lake ringed by hills.

Some had driven from Wisconsin, Michigan or Minnesota, looking to be near the center of the path and away from big cities. Still more arrived after changing plans, swapping out destinations in cloudy Texas for what turned out to be largely clear blue skies in Indiana.

They set up cameras and telescopes in the shade of lifted tailgates. They waited in folding chairs. Fishermen, retirees and college students from nearby Bloomington made fast friends, sharing special binoculars and passing out popsicles.

As the sun became a crescent, the temperatures dropped from more than 80 degrees to just over 70. An American flag that had been fluttering across the rural road hung limp as the wind died down. “Thirty seconds!” someone yelled.

Among the redbuds and silver maples that fringed the hillsides, the light turned the color of ash. Circling turkey vultures took to the trees. Crickets and frogs began to chirp.

People whooped, gasped and yelled as they took off their eclipse glasses to see a black sun ringed with gold. Along the hills around the lake, the sky turned the orange-yellow of sunset in every direction at the same time.

“Oh my God. Oh my God. This is so cool,” said Tim Watson, 60, a retired IT worker who drove from Madison, Wisconsin, with his brother, Chris, 64, for their first total eclipse.

When the sun came back out nearly four minutes later, another gasp went up.

A moment of complexity

A wired world that could place the word “totality” into the collective vocabulary could just as easily track its darker reverberations.

Hotel rooms and vacation rentals along the path were sold out or listed at astronomical prices – good news perhaps for owners, challenges for travelers. Cities and counties declared states of emergency as they braced for floods of visitors, and for weather conditions that might or might not harmonize.

The Texas Eclipse Festival in Burnet County, 50 miles northwest of Austin, included bands and other events to begin Sunday and wrap up Tuesday. Instead, it was canceled Monday over weather concerns including high winds, tornadic activity, large hail and thunderstorms. “Your safety is our top priority,” festival organizers said on their website.

In Oklahoma, a crash around 7:30 a.m. local time squeezed eastbound lanes on I-40, the major transcontinental highway, not far from several state parks that were hosting eclipse events. Multiple crashes were reported along I-35 around Waco, Texas, too, in the path of totality.

Across the country, last-minute watchers scrambled to drug-store counters in hopes of finding a pair of protective eclipse glasses, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology issued warnings about the signs of retina damage in those who viewed without precautions.

And even as the shadow could create a shared experience in fractious times, it could not blunt the many struggles of a nation.

In Las Vegas (where the shadow reached 51% of totality), a gunman in a high rise shot two people to death before taking his own life. In Kansas City (89% shadow), a collegiate athletics body grappled with the politics of who, exactly, may play men’s and women’s sports. In the nation’s capital (87%), lawmakers wrestled with the patchwork of rules for social media, struggling with the privacy rights of Americans in an online world where their eclipse photos and divisive disinformation live side-by-side.

Despite such national shadows, for many on Monday, American divides could not cleave one common, powerful experience.

The end of the path

In Maine, in the eclipse’s last moments in the U.S., Fred Grant watched the moon’s shadow darken his hometown of Houlton.

In the historic logging town near the Canadian border, 6,000 residents had braced for cloudy weather. Instead, they awoke Monday to the thrill of flawless blue skies.

Grant, who owns a local radio station, a pizza place and a movie theater, had been helping plan for this eclipse since 2017, when he watched the last total eclipse in the U.S. on his computer and discovered the next one would pass right through Houlton.

“You’ve got to be kidding,” he recalled thinking.

On Monday, visitors came from as far away as Hawaii and Europe. The town’s hotels were booked, and some visitors parked RVs at a decommissioned Air Force base. The town square filled with music and food trucks. NASA officials set up to broadcast live from Houlton during a three-hour video stream of the eclipse across the country.

Grant said that watching it from the square, surrounded by family and feeling blessed by rare good weather, made the experience as powerful as he could have imagined.

“I had pictured this moment for a long time, and I didn’t really know how I’d feel,” he said. “It was very emotional. I really got choked up. It was overwhelming.”

For a moment, far outside any human control, two celestial lines had intersected. All the experiences beneath them had been part of a shared path.

Then the two orbs in the sky parted ways, each again tracing its own separate arc through space. The darkness ended, leaving each person below to contemplate what remained in the light.

Contributing: Josh Rivera, Deborah Berry and Chris Cann of USA TODAY; Dave Eminian of the Peoria Journal Star, Jon Webb of the (Evansville) Courier & Press.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: The 2024 total eclipse: This is what Americans saw in the shadows