America's 'nasty disease': At 90, civil rights icon Myrlie Evers still marches against racism

CLAREMONT, Calif. – Myrlie Evers felt her temper rising as she sat in the White House theater behind President Joe Biden last month, watching a screening of the award-winning movie “Till.”

She appreciated the invitation and had no complaints about the film’s portrayal of her as the young wife of civil rights organizer Medgar Evers. What riled her was the reminder of the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955, the reminder of what the violence of the civil rights struggle had cost his family and hers. And of the unfinished business that remains.

“The Till case – all of that takes me right back to the time when the love of my life, the father of my children, my husband was shot down dead at our doorstep June the 12th, 1963,” she told USA TODAY, her anger still fresh six decades later. Medgar Evers was targeted by white supremacists for his work as the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, including his investigation of the kidnapping and torture of Till after he was accused of whistling at a white woman.

In 1963, as their three children were waiting for their father to arrive home, she heard gunshots and opened the door to find him in a pool of blood, shot in the back.

“I believe in prayer, and I have prayed so hard: ‘As my God, please release that from me,'" release her rage. "I’ve been carrying it all these years…and I ask the question, Will I ever be free? Will I ever be free?

“Then I look at our system now, I look at America today, and still see so much prejudice and racism," she says. "Who else has to give a life or lives to get us to realize that that is such a nasty disease in this United States of America?"

Myrlie Louise Evers-Williams turned 90 on Friday, a milestone being celebrated Wednesday at her alma mater, Pomona College, where she recently donated her archives. In June, the Medgar & Myrlie Evers Institute in Jackson, Mississippi, will commemorate the 60th anniversary of her husband's assassination with speeches, a gala, and a leadership training summit for members of Gen Z.

Her own life story is a study of persistence.

She fought to bring her husband's killer, Byron De La Beckwith, to justice after two all-white juries declined to convict him. In 1994, he was finally convicted and sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 2001. She took charge of the NAACP in 1995, elected as its chair at a time it was mired in controversy. She waged a quixotic campaign for Congress against a John Birch Society official who had ties to segregationists.

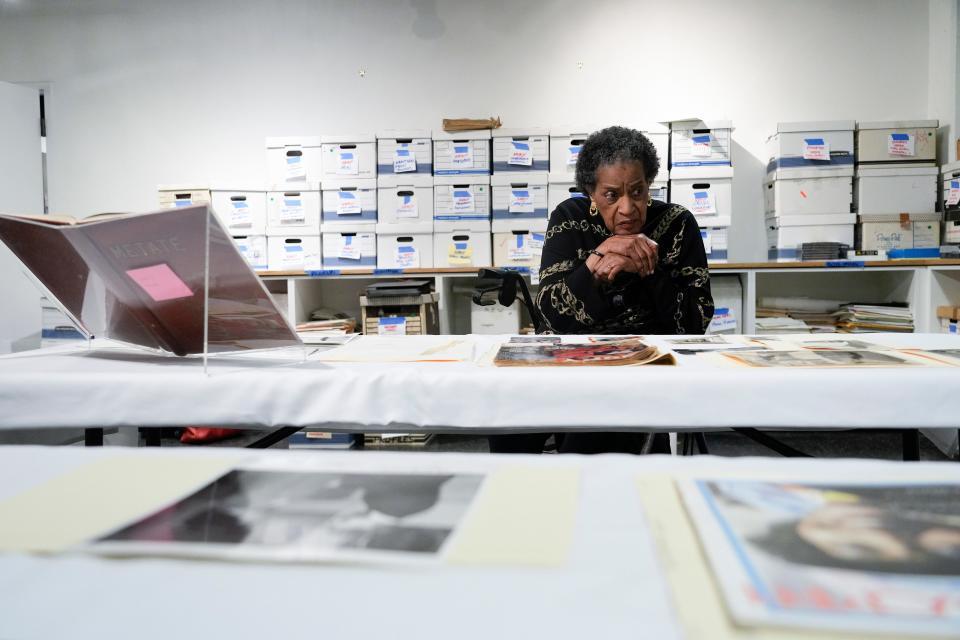

Now her papers and memorabilia are stacked in a windowless basement room at Pomona's Bridges Auditorium, where archivists and students are processing them. The Evers' story is told in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. Their modest house at 2332 Margaret W. Alexander Drive in Jackson was designated a national historic landmark in 2017.

History is all around her, yes. The present too.

Protesting George Floyd's murder

Things are immensely better in the United States now for people of color than they were when her husband was pushing county registrars to allow Black residents to vote and school districts to teach Black and white children in the same classrooms, she says.

But she bristles at the argument by some that the election of the first man of color as president, and now the first woman of color as vice president, means the nation has finished addressing racial injustice.

After George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police in May 2020, she organized a small demonstration, one of the hundreds across the country, protesting police brutality toward unarmed Black men. At her retirement home near Claremont, California, about two dozen residents lined up to march behind her, some carrying signs, many using wheelchairs and walkers.

That November, she was determined to vote in person.

At the time, her seniors' complex was under a COVID-19 lockdown, and the residents were barred from leaving. Then 87 and using a cane, she defied the rules and managed to sneak out, walking down the street to the local polling place just as it was about to close. The workers helped her cast her ballot and then escorted her home, triumphant.

She voted for Democrat Joe Biden, and against Republican Donald Trump. She had rejected the entreaties of her brother-in-law, Charles Evers, to join him when he endorsed Trump in 2016. She responded by endorsing Hillary Clinton, urging voters to "take sides" against what she saw as a rising tide of racism.

As president, Trump offended her when he spoke at the opening of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum and casually referred to her as “Myrlie." To her, that reflected an unbidden familiarity reminiscent of the days when racists would refuse to give a Black person the respect of an honorific – a practice of putdown illustrated in “Till.”

"I just want to say hello to Myrlie," Trump had said in his speech. "Myrlie. Where is Myrlie? How are you, Myrlie?"

“To those people who don’t know me, and I’m being introduced to, respect me with ‘Mrs. Medgar Evers’ or ‘Mrs. Myrlie Evers,’” she said. “For someone to call me by my first name, I don’t care who it is, if this is my first time meeting you, it’s unacceptable to me.”

The offense was presumably unintentional, but it cut nevertheless. She heard it as a reminder of the Jim Crow era and a sign that racism had begun to "bud and bloom" again. She found herself in tears and fury afterward.

'This meant we were going to be OK'

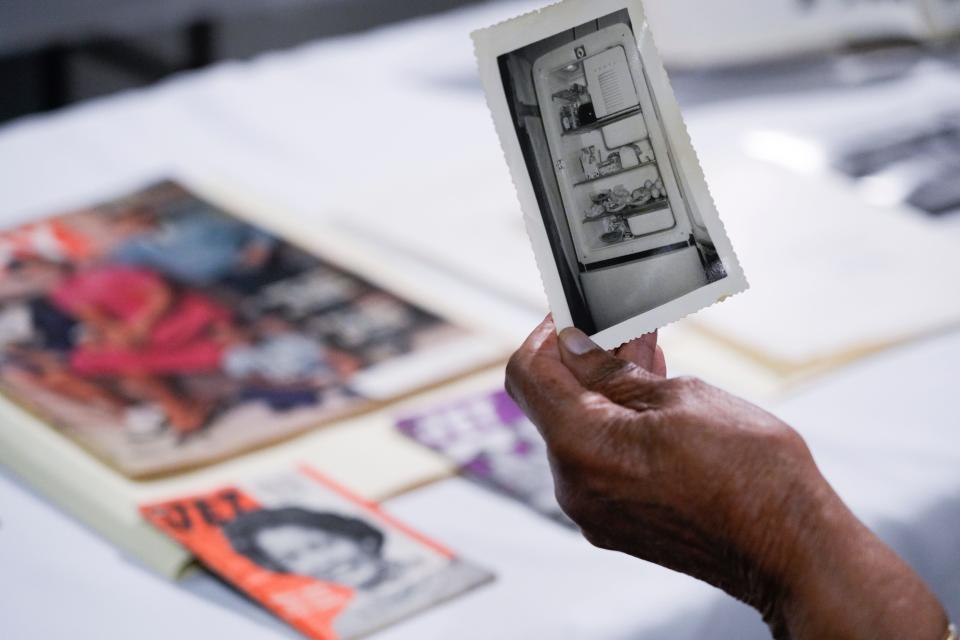

On a worktable spread with the papers and pictures of a lifetime, she picks up a fading black-and-white photo of a refrigerator, its door open to show the food inside. The vintage appliance was in the first apartment she and Medgar rented as newlyweds, she thinks, and something they felt worth capturing in a snapshot.

"A refrigerator that had food in it – this meant we were going to be OK," she says. At the time, she said, Black people in Mississippi belonged to one of two classes: "Poor" and "poor." "Any time you could have a refrigerator, you were considered 'poor,'" meaning you could at least count on having something to eat.

These days, she struggles with mobility and memory. The details from years ago are clearer in her mind than those of last month. The handwritten labels on the boxes in her archives chronicle her own passage from being the widow of a civil rights pioneer to becoming one herself.

"Trials Materials," some of them say. "NAACP," say others. There are papers from her congressional campaign and photos of her with former Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. In 2013, when Obama was sworn in for a second term, she became the first woman and first layperson to deliver the invocation at a presidential inauguration.

Her second husband, Walter Williams, died in 1995.

"She's been one of those matriarchs of the civil rights movement," Mississippi Rep. Bennie Thompson said in an interview. "She was the supportive wife" of Medgar Evers who after his murder "channeled that loss into continuing his legacy."

In 2016, Thompson and every other member of the Mississippi congressional delegation nominated Medgar Evers for the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Now Thompson, the dean of the state's delegation and its only Democrat, thinks it would be "altogether fitting and proper" for the honor to go jointly to Medgar and Myrlie. "A capstone for the two of them," he said.

More: Miss. lawmakers say Medgar Evers deserves Presidential Medal of Freedom

How does she hope to be remembered?

Myrlie Evers suggests the inscription on her tombstone might read, simply, "She was something else." There might be a difference of opinion about what it should say, she notes, with some descriptions more positive than others. "I like the idea of that controversy," she says.

"If there were any ... that would be negative toward my spirit, I think I'd rock in my casket and say, 'Bring them on!'" she declares with a laugh. Then she adds: "I don't run from battles."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Myrlie Evers, civil-rights pioneer, still marches against racism at 90