Anita Hill’s testimony against Thomas ushered in a Year of the Woman. Will Ford bring about another one?

At first what was clear were the similarities — two nominees to the highest court in the United States, both nominated by Republican presidents, both poised to move the court decidedly to the right. And both seemingly assured of confirmation, then hitting a speed bump when accused of past sexual misconduct by women who said they would prefer to have remained anonymous.

But what became clear along the way were the differences, ones that began with but went far beyond the bright turquoise jacket and steely confidence of Professor Anita Hill set against the muted navy and tremulous demeanor of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, the booming righteous anger of Clarence Thomas and the tearful outrage of Brett Kavanaugh. They are differences that reflect the ways in which the country has and has not changed in the 27 years since “who put pubic hair on my Coke?” became a sour national joke.

What has changed most are women. Back in October 1991, as they clustered around television sets in public and private spaces, listening to Hill describe lewd talk from Thomas when he was her boss, there was a feeling of recognition and realization, giving to a common experience a name many had never heard: sexual harassment.

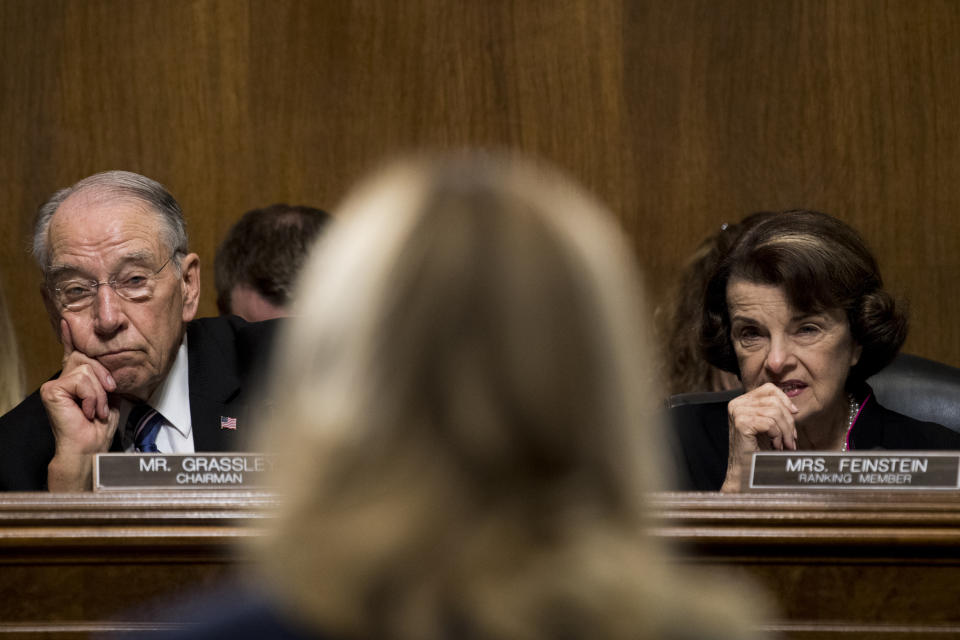

“It happened to you too?” they asked each other, then told their own stories. And, a year after Thomas was confirmed in spite of Hill’s allegations, a record number of women rode the wave of anger to victory in 1992, doubling the number in the House and Senate in what became known as the Year of the Woman. One of those, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, is the senior Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, before which both Ford and Kavanaugh appeared Thursday.

This time, though, there was no slow build. The anger was exposed and waiting, uncorked by the defeat of the first woman with a realistic chance of becoming president by a man with a documented history of sexual misconduct, built to a furor by the Women’s March and the #MeToo movement. Powerful men were toppled by the anger, including two senators — Roy Moore and Al Franken — whose places on the Judiciary Committee were taken by Kamala Harris and Cory Booker. Women didn’t have to get mad, they were already good and mad.

“Every woman I know has been storing anger for years in her body and it’s starting to feel like bees are going to pour out of all of our mouths at the same time,” tweeted Erin Keane, executive editor of the Salon Media Group.

So much about today’s hearing was a response to that decades-old anger. The very fact that it was held at all was in part because one legacy of the Hill/Thomas hearings was to make it politically untenable to refuse to hear testimony from a woman bearing such an accusation. And the particulars — of schedule, of time limits, of who asked the questions — were designed to inoculate the current committee against the same missteps of a generation ago. Like generals fighting the last battle, the all-white, all-male Republican majority on the Judiciary Committee in 2018 understand that the impression left by 11 white men grilling one African-American woman in 1991 were unfortunate at best.

“A little bit nutty and a little bit slutty,” Hill was called in one notable sound bite of the day, and the nascent right-wing media machine suggested that she suffered from erotomania, a sexual obsession with Thomas. Sen. Joe Biden, the Democratic chairman of the Judiciary Committee, left at least one other woman with a similar story waiting offstage, refusing to allow her to testify.

“There is no way to redo 1991, but there are ways to do better,” Hill herself advised in an op-ed in the New York Times 10 days ago, though the ones the committee came up with are not necessarily the ones that she had in mind.

Most notably, the Republican majority hired Rachel Mitchell, an experienced prosecutor of sexual assault cases in Phoenix. She was the only questioner for the first half of the hearing, and while she elicited no new information from Ford, it appeared that she was not hired to. She was there primarily so that a woman could ask another woman about sexual matters, so the men did not have to.

At half-time (the lunch break certainly felt like half-time) TV news anchors, including those on Fox, generally agreed that her testimony was moving and compelling. “This is disaster for the Republicans,” Chris Wallace said on Fox.

But like Thomas, Kavanaugh took the hot seat and came out swinging. Where Thomas called his nomination process “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks,” Kavanaugh called his “a calculated and orchestrated political hit.” In the committee brawl that followed, Mitchell quietly left the stage (she was in the room, it seems, but not on camera and not heard from.)

And that is where the lessons of the Hill-Thomas hearings became most stark. Having learned not to attack the victim, the Republicans of the Judiciary Committee bent over backwards to describe Ford as a victim too. “Dr. Ford and her family have been treated incredibly poorly,” Sen. Ted Cruz said. And Sen. Ben Sasse said “I think Dr. Ford is a victim.”

The nominee had learned the lesson as well. Even while accusing the Democrats on the committee of conspiring to hold off releasing the allegations until the last minute as part of a conspiracy, he stopped short of accusing Ford of being part of it. “I intend no ill will to Dr. Ford and her family,” he said in his statement, his voice breaking as he described his youngest daughter saying a bedtime prayer for “the woman.”

And yet, as Sen. Chuck Grassley gaveled the hearing to a close nearly 10 hours after it began, it was unclear whether the differences from the hearing back in 1991 would lead to a different result. Pundits who were predicting a defeat of Kavanaugh’s nomination in the morning were backing off by evening.

But a change in the makeup of the court was not the only aftereffect of the Thomas hearings. There was also all that anger. It has multiplied and magnified in the years since, and if the outcome of the Kavanaugh hearings are the same as those of the Thomas hearings, the force of that rage is potentially unprecedented, although its direction is predictable.

“If Kavanaugh is confirmed it will be lighter fluid on the midterms for liberal women,” tweeted Danielle Kurtzleben, who covers gender and politics for NPR.

Take the anger that resulted in the Year of the Woman. Add the still simmering fury over Trump’s election a month after the infamous “Access Hollywood” tape. Multiply by “how much #MeToo comes up in my interviews about stuff that is not #MeToo,” Kurtzleben continued, and the likely result is that “this will turn an already energized demographic absolutely furious.”

“Will they turn out?” she asks. “You can bet they will.”

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court:

New Kavanaugh allegations don’t change the fact that it’s all about politics

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: There’s no basis to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

On the calendar with Kavanaugh, a controversial nomination to an appellate court

Whatever happens to Kavanaugh, Trump has already made 2018 the Year of the Woman

Capitol Hill protests mark rising wave of Kavanaugh opposition

Photos: Kavanaugh and Ford testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee