On anniversary of rally, how Charlottesville changed us

The following is part two of our project Charlottesville: One Year Later. For part one, click here.

The senator

In the weeks after the violence in Charlottesville, Sen. Tim Kaine traveled around Virginia, trying to wrap his mind around how something so horrific could have happened in his adopted home state.

It was personal. The Democratic senator knew both of the Virginia state troopers who had been killed in a helicopter crash while monitoring the deadly rally. One of them, Jay Cullen, had flown him all over the state when Kaine was governor. The other officer, Berke Bates, was friendly with Kaine’s wife, Anne Holton, who had worked as Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s education secretary. But it was more than his human connection to the tragedy that shook him.

A mayor of Richmond before his rise in state and national politics (including his stint as Hillary Clinton’s 2016 running mate), Kaine could not grasp how this could have taken place in Virginia, a state that, in his mind, had worked hard to overcome its ugly history of racial division. The first state to enshrine legalized slavery, home of the old capital of the Confederacy, Virginia had seen blood spilled by generations of people over the question of racial equality, but he had been convinced that the state had genuinely turned the page.

“I’m so proud of the arc that Virginia has been on, because I mean bluntly, our state knows hate pretty well. We know division pretty well,” Kaine says. “I really feel like we’ve turned a corner from facing backwards, and still clinging to bad old practices, to facing forward and really trying to be about equality, trying be that state for lovers, trying to be a commonwealth, i.e., a community.”

What happened in Charlottesville, Kaine says, was “very painful … personally painful” for that very reason. This was simply not the Virginia he knew and loved.

“My first thought last August was that we have some people trying to drag us back,” he says. “There are people who want to drag us back, sadly even including the president, who stokes division and hatred, who couldn’t tell who was on the right side and wrong side in a white-supremacy rally in Charlottesville, which demonstrates a level of moral confusion that almost certainly is intentional rather than accidental.”

Touring the state for a series of previously scheduled town halls in the weeks following that deadly weekend, Kaine found himself standing before other Virginians who were as shocked as he was. “This is not who Virginia is,” he told constituents again and again.

But a year later, tensions between the old Virginia and the new remain.

Take Corey Stewart, a Republican official in Prince William County with a history of making racially divisive remarks and ties to the white nationalist movement, including the organizers of the Charlottesville rally. Kaine is running for reelection against Stewart, who denies that slavery caused the Civil War, has been a staunch defender of Confederate monuments and symbols and has made “taking back our heritage” a major talking point of his campaign. Many Republicans have shunned Stewart — including a state Republican Party official who resigned his post when Stewart won the GOP nomination. But other Republicans have not — including President Trump, who endorsed him.

Sitting in his Senate office, where he could not talk about his opponent without running afoul of ethics rules, Kaine declined to speak about Stewart specifically. But a year after Charlottesville, he acknowledged that the same kind of racial tensions and political polarization that led to last year’s rally are still prevalent — not only in his state but in the rest of the country.

“We’re in a battle between love and hate right now,” Kaine says. “It’s a battle about whether we still believe in the two words at the end of the Pledge of Allegiance — are we ‘for all’ or not? And it’s sad that we have to be in that battle in some ways, but in other ways it’s incredibly energizing, and I see evidence of it everywhere.”

He pointed to the large-scale marches — including the Women’s March and the March for Our Lives — and voter turnout in Virginia’s state elections last November, when Democrats captured several key seats, including the governor’s office, surprising political pundits who believed Republicans would be boosted by rural voters, who strongly supported Trump in 2016.

“There was a huge uptick in turnout for an odd-year, traditionally somewhat low-turnout election, and I think some of it was because of Charlottesville,” Kaine says. “Some of it was people wanting to stand up loudly in their own way, say, ‘This is not who we are.’ The president can pretend this is who we are as a nation, but we’re going to stand up and say, ‘This is not who we are.’ And I see that kind of energy out there all the time now.”

Aug. 12, 2017 was “one of the worst days in our history in Charlottesville,” Kaine adds. “Around the state, I think people are standing up even stronger, with a stronger backbone to say, ‘That may have been who we were in the past, but we put all that away and we’re moving to a better future now.’ And if anything, what happened last year has made people even redouble their efforts to make progress.”

— Holly Bailey

The photographer

On July 31, 2017, Ryan Kelly, a photographer for the Charlottesville Daily Progress, gave his two-week notice, announcing that he would be leaving the newspaper for a job as a social media coordinator at a brewery in Richmond.

“Bittersweet news, gang,” Kelly wrote. “After four years as a photojournalist for The Daily Progress, my last day will be August 12.”

That was Saturday, the day violence erupted at a white supremacist rally in downtown Charlottesville, and Kelly, on his last assignment, captured what would become the iconic image of the chaos: the moment when a car slammed into a group of counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer and leaving several others injured.

“They were just marching together, singing, chanting,” Kelly recalls. “It sort of looked like any other march that I would see for any other demonstration or event over the last couple of years in Charlottesville. They weren’t being antagonized; there weren’t any other white nationalists or anything like that. So it actually felt the calmest that Charlottesville had felt all day. I just wanted to get some pictures of them — just standard stuff, people walking, just showing the size of the crowd.”

A few seconds later, Kelly says, he “felt” a car speed past him.

“It was just my one instinct to pick up the camera and follow the car, and just mash down the shutter and take as many photos as I could,” he says. “And so that was the moment.”

Kelly’s photo shows several victims in mid-air as the car, a Dodge Charger, slams into the crowd, and shoes flying as people try to flee.

“The one that everybody knows now [is] the one of the moment of the attack, with people flipping over the car,” he says. “I knew pretty quickly that that was the photo that we needed to put out. We had to clear it with management and lawyers briefly, just over the span of a couple of phone calls, but it was decided pretty quickly that we were going to publish it. So that was up on our website and on the wire pretty quickly. And the response to that, just spreading immediately, was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. It was incredible the way people responded to that photo.”

Slideshow: Violent clashes erupt at ‘Unite the Right’ rally in Charlottesville, Va. >>>

Kelly spent Sunday helping the Daily Progress newsroom, responding to a social media messages and driving himself “crazy” reading news coverage of the car attack. On Monday, 36 hours after he took that heart-stopping photo, he was at his new job at the brewery.

“I decided that going to work and starting something new, and having something else to focus on instead of focusing on all of that, would be the best thing for me,” Kelly says.

His connection to Charlottesville, though, was far from over. In April, his photo won the Pulitzer Prize for outstanding news photography. Kelly and his wife were on a plane returning from Europe when the winners were announced, and found out when they landed.

“I looked up to the Pulitzer forever, even before I was involved in journalism myself,” he says. “I’ve always been very aware and sort of in awe of a lot of those winners. I still don’t know what to think of it, honestly. I don’t know that I’ve really wrapped my head around it fully — it’s just bizarre.”

Kelly still freelances as a photographer, and in May he was hired by the New York Times to photograph the wedding of Marcus Martin, who was captured in his Pulitzer prize-winning photograph.

“He’s the one in the red shoes getting flipped over the car,” Kelly says. “He was engaged at the time; he had pushed his fiancée, Marissa, out of the way, and that was sort of why he took the brunt of the hit of the car. So I was able to be at their wedding, able to meet them for the first time because we’d never actually met. I was able to meet [Heyer’s mother] Susan Bro for the first time too. We all kind of had this shared experience of Aug. 12 in different ways. And being able to connect with them, and to talk about our experiences and what happened then, what had happened since then was really, really nice. And being able to see a happy kind of joyous occasion after all of that hate and violence was a really, really nice opportunity that I’m really grateful to have had.”

Still, it’s an opportunity Kelly would gladly give back — along with the Pulitzer — if he could go back in time and save Heyer’s life.

“I’m still very aware of the fact that it came at the loss of somebody’s life, and dozens of other people were injured [and] two police officers lost their lives,” Kelly says. (The officers were monitoring the events from the air and died in a helicopter crash.) “Like, it was a tragic day, and I was spared most of it. You know, I wasn’t injured; I was just a witness, but I’m very aware that a lot of people had their lives altered forever on that day. So it’s hard to just take joy in something like a Pulitzer when you know that it came because of such a tragic event. Like, if I, in some alternative universe, was given a choice, every time I would prefer that day not happen at all.”

— Dylan Stableford

The governor

Between the funerals for Virginia state troopers Lt. H. Jay Cullen and Berke M.M. Bates, Gov. Terry McAuliffe gathered with members of the state police at a Richmond bar favored by Bates for “an Irish wake for the two Irishmen,” toasting the fallen troopers with Jameson Irish whiskey.

Cullen was McAuliffe’s pilot, and Bates was a longtime member of his security detail.

“They were part of the family,” McAuliffe says. “It was very painful. I cannot tell you how close we were. These folks live with you all day, 24/7. It was like losing a family member.”

McAuliffe had just landed in Charlottesville when he learned their helicopter had crashed.

“They were doing surveillance the whole day. They started early, at 7, 8 in the morning. And they really were in the air,” McAuliffe says. “In fact, that’s why they didn’t come get me. The northern Virginia folks actually brought me down in their helicopter, because they really were all day doing surveillance. And they did. They had footage of the car going into the crowd.”

That footage is expected to be used in the case against James Alex Fields Jr., who is charged with a federal hate crime in the death of Heather Heyer and 28 related counts stemming from injuries to others in the car attack.

Earlier in the day, McAuliffe briefed President Trump on the escalating situation in Charlottesville.

“I had told him we have white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and alt-right screaming vulgarities and all types of things against fellow citizens down there,” McAuliffe says.

Trump, though, did not unequivocally condemn the neo-Nazis. His statement blamed the violence on “both sides.”

“I was astounded, because in my conversation with him, I had briefed him on the situation, told him about these horrible people,” McAuliffe recalls. “They are hateful people. I won’t even mention to you what they were screaming at the African-American members of the community as well as members of the Jewish community. I just wondered to myself, ‘How did we get to this place in America?’ These folks used to wear hoods to disguise themselves. But here they were in Charlottesville. They didn’t feel like they needed to wear hoods. They could just walk down this beautiful little town and scream obscenities and telling members of the Jewish faith that we should burn you like we did in Auschwitz. Things you just really found just hard to comprehend.”

At his press conference, McAuliffe sharply condemned the violence.

“I basically told these folks to go home,” he says. “They’re not wanted. They pretend they’re patriots. They’re not patriots. They’re a bunch of cowards. And to get the hell out of America.”

From McAuliffe’s perspective, some things have changed since that fateful weekend.

“We now have a thing called Incident Command,” McAuliffe says. “Now the State Police is in charge, which is very good. I don’t want to be overly critical of the [local police], but the law, how it was done in Virginia, is that locality … even though I sent down most of the National Guard, locality is in charge. Now, it’s in Incident Command. One person is in charge to do a better job of coordinating all the different entities that are involved.”

Still, McAuliffe knows the violence in Charlottesville was “a very painful, vivid reminder that although we’ve really made significant progress in Virginia, around the country, we still have a lot of work to do going forward.

“It was just a disgusting, unabashed display of white supremacy and neo-Nazism,” he says. “It shocked us, and I think it shocked people around the world.”

— Dylan Stableford

The journalist

By the time she got to Charlottesville, Elle Reeve, correspondent for “Vice News Tonight on HBO,” was already pretty well known among the white supremacist groups gathered there. And with her oversize glasses, she was hard to miss.

“I had been covering these guys for a while and so everywhere I went, they knew who I was,” Reeve says. “There was no slipping into the crowd as anonymous reporter. And they knew who I’ve dated; they knew my boyfriend’s Jewish, so they would yell things about that to me.”

If they didn’t know her before, they do now. Reeve’s breathtaking documentary, “Charlottesville: Race and Terror,” captures white nationalist leaders — including David Duke, Matthew Heimbach and Christopher Cantwell — from the torch march on Friday night to their tense clashes with counterprotesters on Saturday morning, as well as the frantic moments after the deadly car attack in downtown Charlottesville early Saturday afternoon.

Slideshow: White nationalists march with torches in Charlottesville, Va. >>>

Cantwell, a self-described white nationalist and podcast host, was recruited to be a speaker at the rally by Jason Kessler, the event’s organizer.

Reeve, who embedded with Cantwell that weekend, says she did not feel physically threatened — even when she hopped in a van with Cantwell and other neo-Nazis as they raced away from a park.

“I mean, you just make these really quick calculations about the spot, like, ‘Well, I’m not gonna get out unless they drag me out,’” she says.

There was one moment that unnerved Reeve and her crew: when they visited Cantwell in his hotel room.

“This isn’t in the piece, but he started screaming at me,” Reeve says. “He was very, very angry and did start reloading the AR-15 by the end of the interview. Everybody was just like, ‘Alright, this is great, great talking to you and we’re going to go now.’”

Reeve has kept in touch with Cantwell since the documentary aired.

“He called me after it and said that I had represented him fairly,” she says, “But as the consequences from Charlottesville sort of snowballed over time, he started to feel a lot more antagonistic.”

After Charlottesville, Cantwell a posted a video online that shows him fighting back tears after learning a warrant was issued for his arrest. It went viral, and he was dubbed the “Crying Nazi.” Cantwell later turned himself in, and wound up serving more than five months in jail on assault and weapons charges stemming from his use of pepper spray during a clash with counterprotesters.

“I’ve only texted with him since he’s gotten out,” Reeve says. “I did talk to him for like an hour and a half a few weeks ago. Just to sort of see, I don’t know, what he was thinking. I was also just kind of curious whether he’d had any doubts about — I mean, it’s not just white nationalism. He believes in eugenics. We sort of raised science theories. I wanted to push on that and see if he still believes it. He still believes it.”

While most people who recognize the bespectacled Vice News correspondent in public now are friendly, there was one particularly creepy encounter for Reeve in the past year.

“I was going through the security line at the airport for Christmas and the TSA guy recognized me,” she recalls. “And I’m like, ‘Oh, thank you, thank you, thank you.’ And I go through the whole rape-y scan machine, and I get out and I’m putting on my shoes, and he comes over and he tells me this little joke that lets me know that he’s a Nazi. It’s not like he specifically saw my scan or whatever, but it was just really creepy. It was just like this sense of, ‘Oh, they’re everywhere.’”

“I mean, we saw that in Charlottesville the torch night,” Reeve says. “There were hundreds of white nationalists, very well organized. They had a security team. They had vans bringing the protestors. They also did not look like the people upper-middle-class white people in the East Coast think of when they think of racists or white supremacists.

“And I think that’s a really hard reality for people to accept that a lot of these white nationalists are from New Jersey, they went to prep school, they live in nice neighborhoods, they look like people you know. So, I think it’s really important to show that.“

Capturing the harsh reality of Charlottesville was just as important.

“One reason why the documentary got so much attention that it was used to fact-check the president’s statements,” Reeve says. “There are people who wanted to give the idea that this was just like history buffs or, like, people who were civil war reenactors, people who love that Confederate statue — and that’s not what it was about.”

— Dylan Stableford

The reverend

It was a week after the violence in Charlottesville, and Rev. Peter Moon was feeling overwhelmed. He had just officiated at a funeral service in nearby Chesterfield for Virginia State Police Lt. H. Jay Cullen, one of two state troopers who died in a helicopter crash while monitoring the violence.

Moon was in the procession of cars traveling from the church to a private ceremony at Woodlake United Methodist Church, where the Cullen family were members and where Moon had been the lead pastor for many years. What he saw brought tears to his eyes.

“All the cars were pulled over,” Moon recalls. “People had got out of their cars and lined the street as the procession went by with their hands over their hearts, taking their hats off. It was just a very moving, uplifting representation for which I was thankful in the midst of so much ugliness that was represented by a small fragment of our nation.”

“There was this sort of redemptive moment when everybody spontaneously stopped their cars, lined the street and offered their respects when we went by,” he says. “It was overwhelming to be in the midst of such love and support.”

More than 1,200 people attended the service for Cullen, who was remembered as a “silent giant,” loving husband, father of two teenage sons.

“He listened more than he talked,” Virginia Col. W. Steven Flaherty said in his eulogy at the funeral. “And when he said something, it was because he had something relevant to say.”

“He was just a great guy,” Moon says. “He was a guy who was funny, always interested, seeking. He was a man who was passionately in love with his wife and his family and he was an athlete. He just had this consistent glimmer in his eye. He’s the kind of guy you always want to be around.”

Moon says Cullen’s legacy will live on with the ones he left behind.

“When you have somebody of his caliber and character you still see it in his wife and his children and the bonds they have as a family,” he says.

“It won’t be the same when I step into that helicopter without Jay in the right front seat, with ‘Cullen’ on the back of his helmet,” Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe told mourners at the service.

During the service, police helicopters from nine states flew over the church one by one, repeating the tribute conducted for Trooper-Pilot Berke M.M. Bates’s funeral the day before.

McAuliffe gave the eulogy there too.

“He was a real character,” McAuliffe said before relaying his favorite story about Bates.

“My son had been deployed to Iraq,” McAuliffe says. “He’s a Marine. I remember it like it was yesterday. I was in the lobby of the governor’s mansion, about to go out for the day, and I was talking to Berke. And he said, ‘I want you to know I just sent a care package to your son.’ I thought razor, cigar, that sort of stuff. I said, ‘How nice of you, Berke.’ And he said, ‘I sent him a bottle of Irish whiskey.’ And I said, ‘Burke, it’s a Muslim country. You can’t have alcohol in a Muslim country.’ And he said, ‘Oh no, no, no, don’t you worry about that, governor. I put it in a Listerine bottle. They’ll never figure it out.’” The care package was delivered, McAuliffe adds, but the bottle never quite made it.

According to McAuliffe, Bates had left his detail about two months earlier for the aviation unit.

“His dream had always been to fly,” McAuliffe says. “And he went and with his own money bought the manuals to learn how to fly a helicopter. He’d only been in the air probably a month. But he died doing exactly what he loved to do.”

In April, a helipad was dedicated in Bates’s honor. In February, a hangar at the Virginia State Police Aviation Base in Chesterfield was named for Cullen.

Such gestures help the healing process, but they’re also a reminder of the healing that’s still to come.

“To lose their lives because of an incident, because people came in to spew hatred — it has to be a learning moment,” McAuliffe says. “How do we go on? How do we go forward from here?”

“We need to prayerfully seek healing,” says Moon. “Racism does not go away easily nor has it gone away. It’s a continuing battle. One of the lessons of Charlottesville is there’s still a lot of work to be done.”

— Michael Walsh

The historian

Edward Ayers, historian and former University of Richmond president, had no way of knowing what would come of his talk at the Virginia Festival of the Book in March 2013.

“It was a talk about memory,” Ayers says, “and how we remember some things and not others.”

He adds: “I wasn’t there on a crusade.”

Near the end of the talk, Ayers was asked about Charlottesville’s Confederate statues by Kristin Szakos, then a member of the City Council, and whether they should consider removing them.

“You would have thought I had asked if it was OK to torture puppies,” Szakos recalled in a podcast, hosted by Ayers, a few months later.

“I’d been talking about the monuments for a long time,” Ayers says. “Nobody remembered how they got there or what they were for and what they meant. And so I just called people’s attention to them because they’re there.”

But the talk sparked Szakos and others to take up the cause. In 2015, as clashes over Confederate symbols raged in several Southern states, the debate over what to do with Charlottesville’s boiled to the surface.

In 2016, Charlottesville’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials and Public Spaces was formed to address the city’s Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson statues.

Ayers was familiar with the task force but wasn’t necessarily attuned to what was brewing in the small college town.

“I was a lot more focused on Richmond, which has some legacy of the Civil War,” he says.

Yet Ayers found himself back in Charlottesville just as the Unite the Right marchers descended upon the city to oppose the statues’ removal.

The University of Virginia had scheduled a series of “teach-ins,” alternative activities that would be focused on progressive causes while the alt-right was in town. On Aug. 12, Ayers was scheduled to teach a class about voting rights.

As Ayers and his wife got ready to head to the school, five miles away, they followed the clashes on television. “We just watched it unravel before our eyes,” Ayers says.

“I think we lost our innocence,” he says. “White people lost their innocence that weekend and now can’t imagine that the statues just don’t mean anything, that all they are were testimonials to good faith to the past. Now they see that they are politically charged and that public spaces matter and that everybody has a claim to the public spaces in the cities where they live. I think it was an eye-opening experience for a lot of people.”

Ayers sits on Richmond’s Monument Avenue Commission, which has been responsible for what the city will do with its own Confederate statues — whether that is removing them, erecting statues commemorating those outside of the Confederate past or explaining what they truly stand for.

“Sometimes people say that this is like the Taliban removing statues,” Ayers says. “No, this is a deeply democratic process for the first time. For the first time, elected officers, city councils and general assemblies are reckoning with the fact that these were put up when black people had no vote and no political power. If the statues are going to be among us, they need to be educational. They need to tell their story, their full story.”

— Kadia Tubman

The city councilman

In the months leading up to Charlottesville, Wes Bellamy had a target on his back.

The city council member’s efforts to remove the Confederate statues in town and his defense of Black Lives Matter had drawn the ire of Jason Kessler, the organizer of the Unite the Right rally.

“I know what it’s like to be attacked by him and his minions,” Bellamy says.

Bellamy, 31, is an Atlanta native who moved to Charlottesville after graduating from South Carolina State University in 2009. He became the youngest person ever elected to the city council when he won a four-year term in 2015 and was the only African-American on the council before Nikuyah Walker’s election. He said early on in his campaign community members suggested taking down the statues, which garnered death threats and hate mail. It also drew the ire and attention of Kessler.

In late 2016 Kessler published old tweets from Bellamy that included vulgar language, and Kessler filed a petition for a recall election. Bellamy apologized and resigned from the state board of education, but he retained his seat on the city council after a judge dismissed the petition.

A year after the rally, Bellamy says he doesn’t pay much attention to Kessler but that the alt-right organizer serves a purpose.

“Maybe he didn’t want to, but he brought a lot of people in our community together because we had to denounce hate,” Bellamy says.

One of Kessler’s supporters in the movement to remove Bellamy was Corey Stewart, who is currently the Republican candidate for U.S. Senate in Virginia. Stewart has aligned himself with white supremacist groups and has been an outspoken supporter of preserving Confederate monuments. Bellamy says that Stewart’s prominence makes it harder for people to ignore white supremacy.

“This is not about a statue,” he says. “This is about the covert and overt racism and the systemic issues we’ve had in our country for generations.”

Bellamy said that in the wake of the violence in Charlottesville there are still a number of issues to address but that there has been “beauty” in the awakening of citizens. He added that community members who had been apathetic about taking down statues and addressing issues in the city have come forward with their support.

“There have been people saying, ‘Wes, sorry we didn’t support you initially’ or ‘Sorry we didn’t quite get it initially,’” Bellamy says. “But now they’re going to use their privilege or voice or platform, whether it’s big and small, to actually address these issues of white supremacy.”

A judge on the Charlottesville Circuit Court will rule on the future of the statues later this year. Bellamy expects that whatever the court decides there will be an appeal, so a final decision would likely come from the state supreme court in early 2019.

Bellamy says there has been pushback from some who would prefer things just return to the pre-rally normal, but that the city is pushing forward.

“I don’t want for people to think of Charlottesville as just a hashtag, this place where white supremacy reigns supreme,” Bellamy says. “There’s still a lot of great things in Charlottesville, and we’re no different than many other communities throughout the South. We may have took a punch in the face, but we weren’t knocked down — we came back stronger.”

— Christopher Wilson

The white supremacist

Last August, Christopher Cantwell traveled from his home in Keene, N.H., to speak at an alt-right rally in Charlottesville. Nearly a year later, he’s finally left Virginia for good — or at least for a court-ordered five years.

The host of a white nationalist internet radio show, Cantwell became more or less the face of the ill-fated Unite the Right rally thanks in large part to a Vice News documentary in which he was featured prominently. His own tearful YouTube video, posted in the aftermath of the violent clashes, earned Cantwell the nickname “Cryin’ Nazi.”

Cantwell later surrendered to police and was charged with felony assault stemming from his use of illegal tear gas during a clash with counterprotesters on the torch-lit march through the University of Virginia the night before the rally. He wound up serving 107 days in a Charlottesville jail and more than seven months under house arrest. Last month, he pleaded guilty to two counts of assault and battery and to violating the terms of his bond by referring to his victims on social media and during his radio show — which he hosted from jail. In exchange for his guilty plea, Cantwell was released from jail — and banned from Virginia for five years.

“It feels good to be home,” says Cantwell, who insists he was framed and coerced into pleading guilty. “It feels good to be done with this whole mess.”

Cantwell’s Charlottesville-related legal woes aren’t exactly behind him; he is the target of an ongoing civil lawsuit by two counterprotesters, including activist Emily Gorcenski, who was pepper-sprayed during the march. (As part of his guilty plea, Cantwell admitted to violating the terms of his bond by talking about Gorcenski and another victim on social media and his radio show. He was fined $250.)

In the closing scene of the now-infamous Vice documentary, Cantwell — sitting in a hotel room amid an arsenal of weapons — reflects on the violent clashes that resulted in one death and several injuries, telling correspondent Elle Reeve that he considers the weekend a victory for his side.

Looking back on it, the 37-year-old former libertarian now says he would have “done a lot of things different.”

“I wouldn’t have gone to that thing if I’d realized what a f***ing catastrophe the people who were putting it together were,” he says, referring to Unite the Right organizer Jason Kessler as “a literal f***ing mental patient.”

To be clear, Cantwell’s regrets about his participation in Unite the Right have little to do with the views espoused by its participants, but rather are based on what he sees as Kessler’s poor planning and his failure to properly prepare for the potential blowback against a gathering of hundreds of white supremacists and neo-Nazis in a city “run by communists.”

“The idea that anybody would follow him into something as dangerous as what we walked into down there is absolutely insane,” Cantwell says.

Despite repeatedly referring to himself as “an entertainer,” Cantwell is unrepentant about his racist and anti-Semitic worldview. In fact, it seems to have only become further solidified in the past year.

“My new favorite catch phrase on the show is, ‘Keep on calling everybody a Nazi, and eventually you’re gonna be right,’ because that’s literally what happened,” Cantwell says. “So I’m in jail, held without bond, without probable cause, facing 60 years in prison because a Jew and a tranny framed me for a crime, and everybody’s calling me a Nazi. Well, you know what? I’m starting to think the Nazis had a f***ing point.” (Cantwell only faced 12 months in prison for his Charlottesville-related charges.)

Though nominally about the preservation of a statue honoring Confederate Gen Robert E. Lee, the underlying objective of the Unite the Right was to bring various factions of the largely internet-based alt-right movement together in real life. For many Americans, the sight of men, most of them young, marching through the University of Virginia campus carrying tiki torches and chanting things like “Jews will not replace us!” served as a shocking realization that such attitudes were still alive in America.

Whatever unity may have existed among the alt-right prior to Charlottesville was largely fractured in its aftermath as efforts to ban some of the movement’s most vitriolic members from social media and crowdfunding platforms drove them further into the darkest corners of the internet. Fears of losing their job and being labeled a Nazi discouraged many from publicly affiliating themselves with the alt-right, while others who sought to channel the momentum of Charlottesville into a real-life political and social movement proved to be full of hot air. Big-name figures in the world of white supremacy, including Cantwell, have discouraged their followers from attending Kessler’s Unite the Right 2, slated to take place in Washington, D.C., this coming weekend.

Likewise, Cantwell disputes the notion that, post-Charlottesville, many people who might have previously held racist views in secret are now more comfortable expressing them.

“I think it had the exact opposite impact of that,” he says. “However, what I will say is that the people who were comfortable voicing them, they’re fanatics now.”

— Caitlin Dickson

The activist

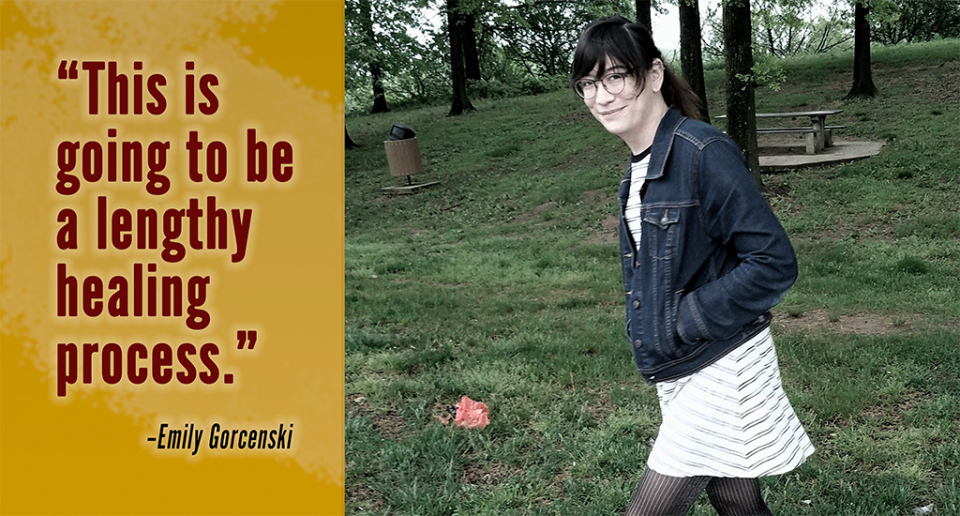

Emily Gorcenski lived in Charlottesville for nearly a decade before she first got involved with local activism, in March 2017.

A few months later, when she heard there was going to be a rally of white supremacists and neo-Nazis in her adopted hometown, Gorcenski felt obligated to protest.

“It would be unconscionable to not go to oppose their messages of hate,” Gorcenski says. “When the Nazis come you don’t run away.”

Gorcenski, a data scientist who identifies as transgender and whose activism had largely focused on transgender rights, accused white nationalist Christopher Cantwell of using pepper spray against her and other counterprotesters at a torch-lit march through the University of Virginia campus the night before the Unite the Right rally was slated to take place. Cantwell recently pleaded guilty to those charges.

Though Gorcenski is currently embroiled in a separate civil dispute with Cantwell, she said she’s “relieved that he’s admitted his responsibility and taken some measure of accountability for his actions and his violence at UVA that night.” Still, she considers the torch march to be among the most disturbing moments from that weekend.

“In the scope of things, the 300 men with torches surrounding some 20 or 30 students and intimidating them, and shouting slurs at them, and then doing violence to them, and to all of us, is the kind of gross mob violence that we were afraid of,” Gorcenski says. “To me, I think that sticks out as one of those traumatic memories that will never go away.”

For Gorcenski, the trauma of Unite the Right lasted well after the weekend was over. Over the past year, she says she’s experienced continuous harassment — both online and in person — as a result of the criminal case against Cantwell.

“I’ve had my personal details leaked on the internet. I’ve received death threats,” Gorcenski says, adding that strangers even showed up at her house in Charlottesville with guns. “There’s multiple times when I’ve felt … threatened for my physical safety.”

Ultimately, she says the harassment drove her to look for jobs outside the country. In late May, she moved to Berlin, where she will soon begin work as a data scientist for a consulting firm.

“It’s a night and day difference being in Germany versus being in Charlottesville, or really just being anywhere outside of Charlottesville,” she says. “It’s a huge impact on mental health and well-being, and I’ve talked to many people in the Charlottesville community, activists and non-activists, who have echoed similar sentiments that just being out of town is like a breath of fresh air.”

Of course, she notes, “the online harassment knows no borders, but I have less risk of physical threat.”

Gorcenski says she’s “still actively working against the white supremacist movements,” though she’s had to take a more remote approach to activism since moving overseas. “I can’t be out there with my friends and comrades on the streets if I’m in Berlin.”

One day, she would like to return to Charlottesville.

“It is my home,” she says. “I still own a home there. My wife is still there, and it’s a place that I’ve come to love, and I would love to be able to return someday when everything has settled.”

For at least the next few years, however, Gorcenski says she thinks it’s best to stay away.

“This is going to be a lengthy healing process,” she says.

— Caitlin Dickson

The victim

A few weeks ago, Marcus Martin was flipping through a magazine in the checkout line at Walmart with his new wife, Marissa Blair, when he looked down to see the photo, and became overwhelmed with emotion.

“That picture that was taken … it speaks volumes,” Martin says.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning photo, taken by Ryan Kelly, captured Martin suspended in the air seconds after he pushed Blair out the way of a Dodge Charger that plowed into a crowd of demonstrators protesting the white supremacist rally.

The night before that photo was taken, the couple had watched the clashes between protesters and white nationalists on Facebook Live. “We were like, ‘Wow, this is really happening in Charlottesville.’”

The next day, they joined their friends, including Heather Heyer, for the counterprotests in the city. When they arrived, they saw the Vice News camera crew recording.

“They walked right past us,” Martin recalls. “We were looking at them, staring. Marissa got scared and said, ‘Babe, I don’t think this is a good idea.’ And I was like ‘Baby, we’re here now.’”

Martin held onto Blair and told her, “Don’t let my hand go.”

It was then, not long their arrival, when James Alex Fields Jr. allegedly drove his car into the crowd where Martin, his fiancée and their friends stood, hitting Martin and killing Heyer.

“I wish we would’ve listened [to Marissa],” said Martin. “But then it still would’ve happened to somebody else. You can’t stop stupid; you can only try to prevent it.”

“What happened was painful because Heather was right there in front of me,” adds Martin, who suffered a twisted tibia, broken ankle and three destroyed ligaments. “Her life was taken that day, and nothing can ever ever fix that.”

Nine months after the rally and the death of their friend, the newlyweds honored Heyer at their wedding by adorning almost everything with Heyer’s favorite color, purple. The couple also remembered Blair’s father, who passed away two months before the wedding.

“We were still grieving from Aug. 12, and that right there was another deep cut,” Martin says. “It was like she lost her best friend.”

Despite so much loss, the Martins were grateful to see the community rally together for their wedding, which was completely organized and run by volunteer vendors.

And while the Martins have a new anniversary, May 12, to mark on their calendars, they will also be saving a place three months after that date. “Aug. 12 wouldn’t be Aug. 12 without Heather,” Martin says. “We got to keep her alive. We can’t forget about her.”

For Martin, forgetting isn’t even a possibility.

“It’s something that you would never ever forget,” he says. “You really try hard not to think about it … even down to that car. I would be riding through town, me and Marissa, and that car would just appear — and it looks exactly like the car that hit us. It’s the same make, same color and everything. It makes my body cringe.”

The Martins live 20 minutes from Charlottesville, but Marissa actually works downtown, three streets from where they got hit.

“She has to reopen that scar every day,” Martin says.

“What happened last year wasn’t about a statue,” he says. “You don’t need walk around with ARs and AKs and guns if you were coming for a peaceful rally. It was to cause intimidation, to scare people, to strike fear.”

This year, Martin and his wife are hosting a family reunion the day before the Charlottesville anniversary to “take that energy into the next day, into the community,” and “make this Aug.12 better.”

“I know I can’t change the world,” Martin says. “But if you start by making that little step every single day, eventually change is going to happen. We’ve got to start somewhere.”

— Kadia Tubman

Additional photo credits:

Photo credits for image insets above: (Bro) Brian Snyder/Reuters, (Walker) Eze Amos, (Kaine) Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call, (Kelly) Steve Helber/AP, (McAuliffe) Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images, (Reeve) Vice News Tonight/HBO, (Moon) Scott P. Yates/progress-index.com, (Ayers) courtesy of Edward Ayers, (Bellamy) Steve Helber/AP, (Cantwell) Vice News Tonight/HBO, (Gorcenski) Jayce Slaughter, (Martin & Blair) Andrew Shurtleff/The Daily Progress via AP.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News on Charlottesville, one year later:

New Charlottesville mayor vows to keep pushing ‘until it’s done right’

Vice News journalist on what it’s like to be recognized by Nazis

‘Cryin’ Nazi’ blames rally organizer for Charlottesville ‘catastrophe’

Charlottesville photographer would return Pulitzer if he could save Heather

Former Virginia governor remembers troopers who died in Charlottesville

Trump’s ‘both sides’ response to Charlottesville still elicits anger