Arizona Republic, news outlets win in fight over unconstitutional police video ban

Arizona has agreed to pay news organizations, including The Arizona Republic, and the ACLU of Arizona $69,000 in attorneys fees, according to files in a pending settlement from a First Amendment lawsuit over an attempt to restrict public access to police actions.

The proposed settlement shows that Kris Mayes will, as attorney general, pay Arizona news outlets $46,000 and the ACLU $23,000 for attorney fees and costs. Proceeds to the news outlets will be divided.

This all comes out of a controversial state law last year that banned people from filming police from within 8 feet. The law, House Bill 2319, was challenged by media organizations, including The Republic, arguing that it violates the First Amendment. Passage of the bill pitted concerns for protecting free speech against a desire to preserve the safety of police on duty.

A proposed order filed in court this week would, if approved as expected, prohibit enforcement of the police video ban and declare it unconstitutional. U.S. District Court Judge John Tuchi still has to approve these orders for them to become final, and the decision will be made on his schedule.

The filings this week were a win for news media organizations and anyone who might want to record police officers while they are on duty.

"We're certainly grateful that the Attorney General's Office has recognized that this law was unconstitutional on its face and should be struck down by the court," said Matthew Kelley, the attorney for the news media plaintiffs.

He said they are also happy that the office has agreed to a settlement for a portion of the attorney's fees because of the cost of having to bring on the lawsuit. But Kelley said there is a bigger picture of what the outcome will mean if the judge sides with them.

"The real-world bottom line is that for journalists in particular, this law was dangerous because it would allow police officers to essentially create the crime, give a warning, and then arrest somebody even if they didn't have an opportunity or ability to move beyond eight feet away from officers," he said.

Kelley went on to say that the law, particularly for journalists, "chilled" their ability to report the news about what police are doing, and it would do the same to any other person who simply wanted to film police for whatever reason.

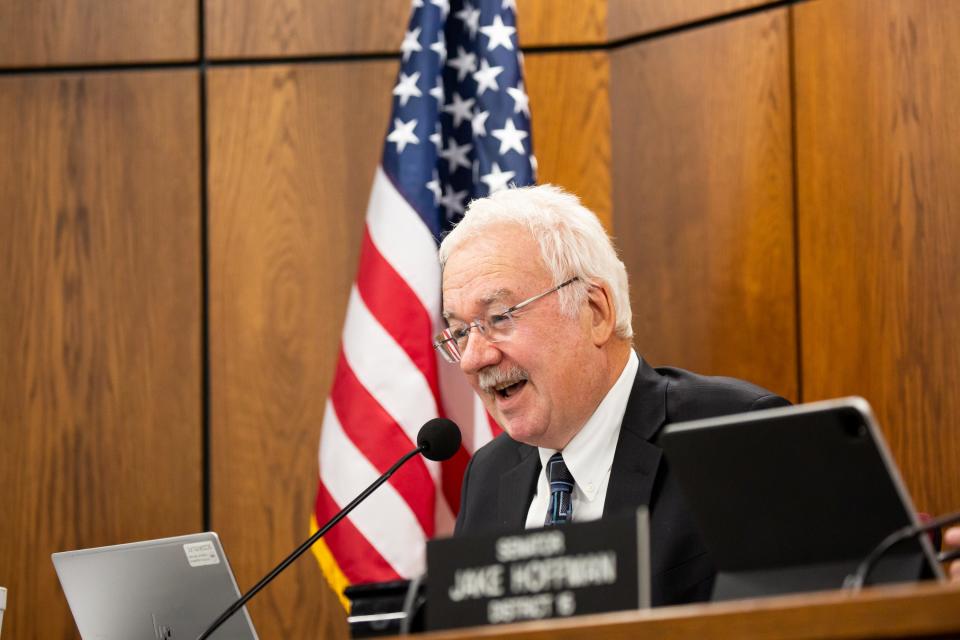

State Sen. John Kavanagh, the Fountain Hills Republican who sponsored the bill when he was a state representative, told The Republic on Thursday that he was unaware of the proposed order to prohibit enforcement of the ban and it being declared unconstitutional. Nonetheless, he said he opposes what the outcome will mean for his bill if Tuchi approves it.

"This is a case where the attorney general didn't defend it," Kavanaugh said. "Clearly, this outcome is not unexpected. But I am certainly not happy with it."

The police video ban bill was crafted in the wake of a string of high-profile recordings of police misconduct, often taken by protesters. Opponents of the measure had said the bill was going to interfere with holding police accountable. But Kavanagh, a former police officer, drafted the bill to create a buffer around police interactions so officers can do their work.

Kavanagh said he hoped that Mark Brnovich, who was attorney general at the time when the lawsuit was filed, was going to defend the law so if the court laid out the issues with the law he could correct them.

"I only hope that whatever the judge comes out with this time contains such an explanation so that I could recraft it (the law) to be constitutional because I believe that police need to be protected from people who would stand 1 foot behind them" during intense encounters.

In one of the court filings this week, the media organizations and the Attorney General's Office listed reasons why the law was unconstitutional and violated the First Amendment — one of them being that there is a "clearly established right" to record law enforcement officers while they are engaged in their official duties.

Last summer, Gov. Doug Ducey signed the police video ban bill, making it illegal for anyone to film police activity from within 8 feet. Violators would face a misdemeanor charge. The law was supposed to go into effect last September but before it could, Tuchi halted the ban and sided with media organizations who raised the First Amendment concerns.

At that time, Tuchi determined that the media groups were "likely to succeed on the merits," and noted that the law represents a content-based restriction on speech that fails strict scrutiny, Kelley told The Republic at the time. Content-based laws are usually considered unconstitutional and subject to the highest form of judicial review, which is strict scrutiny.

Tuchi then set a one-week deadline to give agency officials to defend the law if they choose to.

Last year, the Attorney General's Office declined to defend the new law, saying it was not "the appropriate" agency to do so, according to the AZ Mirror. The AZ Mirror also reported that the other defendants in the initial case, the Maricopa County Attorney and Maricopa County Sheriff's Office, declined to defend the law for the same reason.

“Having this matter settled and this law permanently off the books is a victory for all people to exercise their First Amendment rights to record government officials from a public place,” said Greg Burton, Republic executive editor.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona Republic, news outlets win in fight over police video ban