As president, Biden wants more 'civility.' His rivals want more power.

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Democrats want to accomplish some very big things in 2021. Extending Medicare to every American. Mobilizing the entire U.S. economy to combat the existential threat of global warming. Creating a pathway to citizenship for 12 million undocumented immigrants. The list goes on.

But how?

By giving the next president more power — at least in the view of a growing number of Democrats running to be the next president.

Consider next November’s likeliest outcome. Based on current polling, one of the Democratic candidates — perhaps Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg or Kamala Harris — could well be the next president. The odds also favor a Democratic House. But while Democrats can dream of recapturing the Senate, the best they can hope for is 52 or 53 seats — nowhere near a filibuster-proof supermajority of 60.

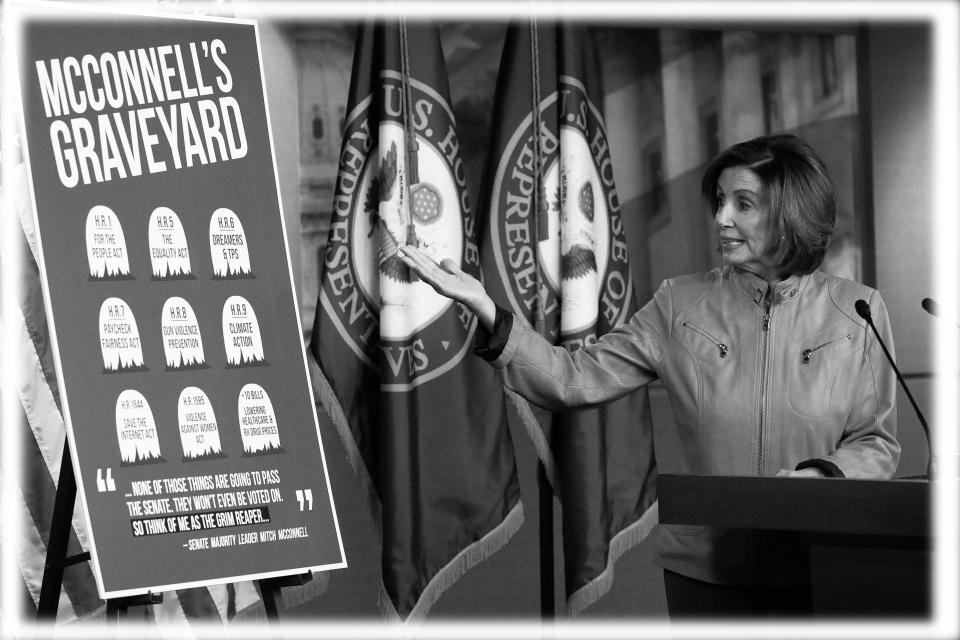

As a result, Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell will still have the power to block most, if not all, Democratic legislation. And so the most important question of the 2020 presidential race, at least for Democrats, isn’t “What will you do as president?”

It’s “How will you do anything at all?”

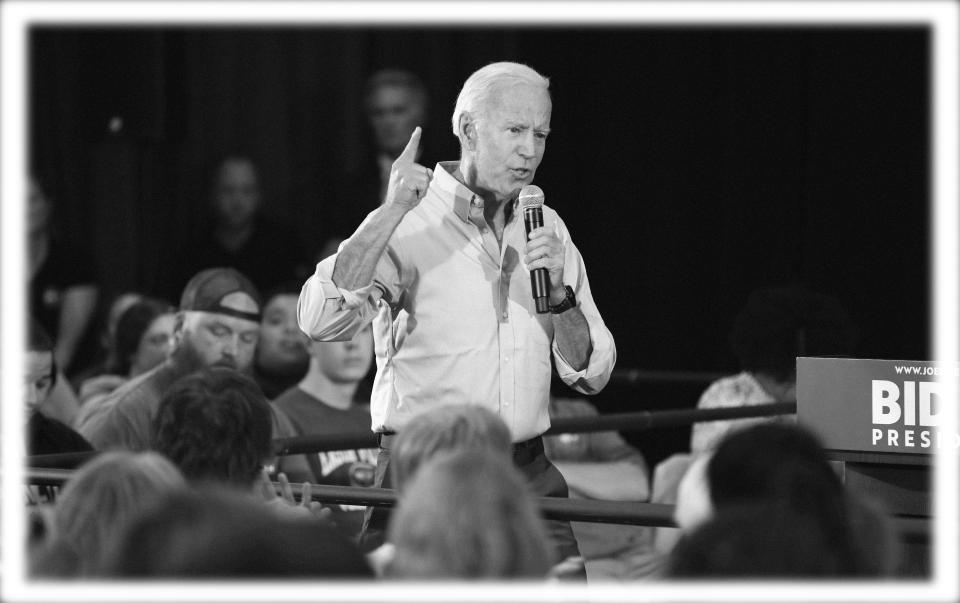

Biden, the early frontrunner, recently offered his answer to that question. For months the former vice president has been predicting that if he wins the presidency in 2020, Republicans will stop stonewalling and start cooperating.

“With Trump gone you’re going to begin to see things change,” Biden said in early June. “Because these folks know better. They know this isn’t what they’re supposed to be doing.”

Asked by the Washington Post’s Dave Weigel why Republicans would want to work with Biden after making it their mission for eight years to obstruct his old boss, Barack Obama, the former Delaware senator insisted that he could persuade them. How? By showing that cooperation is “in their own self-interest” — then threatening to “go out and campaign against [them]” if they refuse. He even went so far as to cite his history of working with segregationist senators as an example of how he would “get things done.”

“The system is not broken; the politics are broken,” Biden told Weigel. “The system’s worked pretty damn well. It’s called the Constitution. It says you have to get a consensus to get anything done.”

Yet Biden’s conviction isn’t shared by some of his leading rivals for the Democratic nomination, who describe it as wishful thinking (or worse, in the case of working with segregationists). For them, the only immediate solution to Republican obstruction isn’t, as Biden put it, for the president to “be a lot more civil.”

It’s for the president to be a lot more powerful.

“This business that Democrats play by one set of rules and Republicans play by a different set of rules — those days are over when I’m president,” Elizabeth Warren recently told Vox’s Ezra Klein. “We’re not doing that anymore.”

Experts, meanwhile, are worried about the escalating political conflict that could ensue.

“We should not be happy about this,” says Norm Ornstein, the author of “It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the Politics of Extremism.” “We’re approaching a fundamental breakdown of the system.”

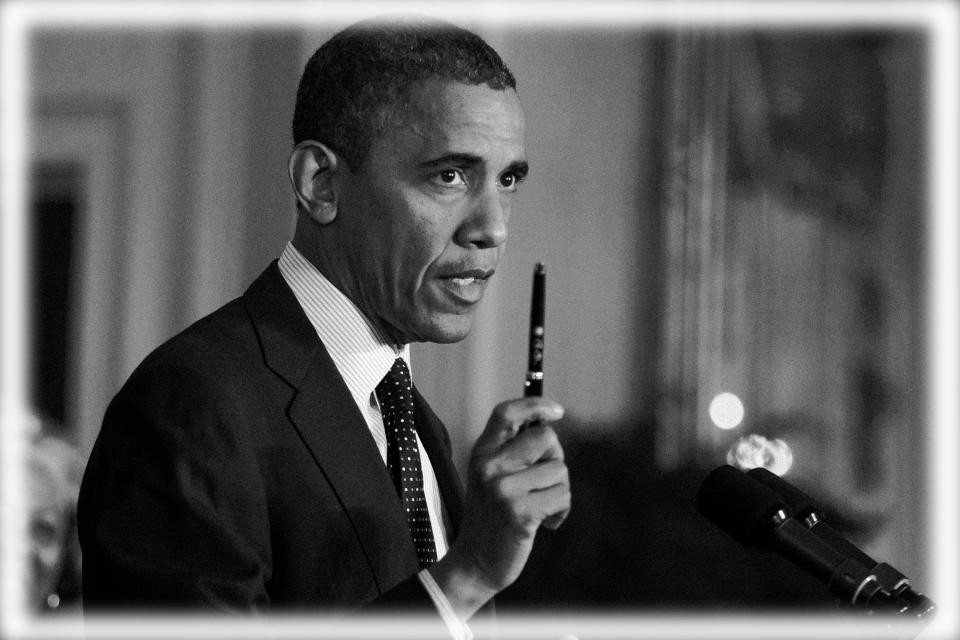

The growing Democratic push for more presidential power has its roots in a U-turn Obama made about halfway through his presidency — and a lingering sense of regret among progressives about how much more he could have accomplished if he’d reversed course earlier.

Presidents have always strained against — and stretched — the limits of their power. Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus during the Civil War. FDR invented the modern administrative state during the Great Depression. George W. Bush pushed the boundaries of intelligence-gathering and law enforcement after Sept. 11.

But something changed during the Obama administration.

In 2009, the young Illinois senator took office vowing to implement an era of bipartisan cooperation. He spent the first two and a half years of his tenure trying to meet the opposition halfway.

What he didn’t realize is that Republicans had already decided not to budge. On inauguration night, as Obama celebrated at various balls, a group of 15 top GOP lawmakers met with former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and messaging maven Frank Luntz at Washington’s Caucus Room restaurant to plot their comeback.

“If you act like you’re the minority, you’re going to stay in the minority,” said California Rep. Kevin McCarthy. “We’ve got to challenge them on every single bill.” As Robert Draper later reported in his book “Do Not Ask What Good We Do: Inside the U.S. House of Representatives,” the group agreed to “show united and unyielding opposition to the president’s economic policies.”

The obstruction began immediately. When Obama’s stimulus package came up for a vote that February, the entire House Republican caucus voted against it. Under Carter, Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Clinton and George W. Bush, the Senate confirmed between 79 and 93 percent of the judicial nominees put forward during each administration's first 18 months. The confirmation rate during Obama’s first year and a half was 43 percent, or roughly half the historical norm. In 1981, 37 Senate Democrats voted for Ronald Reagan's tax cuts; 20 years later, 12 Senate Democrats voted for George W. Bush’s. In contrast, Obama pushed seven major bills before Republicans captured the House in 2011. Those proposals, combined, received a total of 15 Republican votes in the Senate.

Things only became less collegial thereafter. In the 2010 midterms, Republicans gained 63 seats in the House and six seats in the Senate — not enough for unified control but more than enough to stifle Obama’s entire agenda. And that’s what they did, breaking all filibuster records by blocking legislation at more than twice the rate of any previous Congress. Over the remaining six years of Obama’s presidency, there were more successful filibuster threats in the Senate (289) than there had been from 1919 to 2006.

And that led Obama to decide he’d had enough (as the author of this article reported in 2012). Under the umbrella of a new governing (and messaging) strategy — “We Can’t Wait” — he began to issue executive orders and administrative directives intended to accomplish what he couldn’t get through Congress. A new program to help homeowners refinance their underwater mortgages. A multipart plan to ease terms on student loans. Waivers from No Child Left Behind education requirements. Waivers from welfare work-participation rules. And finally, in 2012 and 2014, an order deferring the threat of deportation for millions of “Dreamers” who'd been brought to the United States illegally as children — even though he’d previously insisted that the only way to deliver relief was by muscling the long-stalled DREAM Act through Congress.

"We live in a democracy," Obama had said in September 2011. "You have to pass bills through the legislature, and then I can sign it. And if all the attention is focused away from the legislative process, then that is going to lead to a constant dead end."

Not after 2012. By the end of his second term, Obama had added cutting carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants, strengthening gun background checks, requiring insurers to cover birth control and raising labor standards for federal contractors to his go-it-alone list.

Taken individually, none of Obama's unilateral maneuvers was extraordinary, conservative hysteria aside; presidents had been making similar moves for decades. And yet together they represented a break from the past. Unlike most of his predecessors, Obama did not expand presidential power to meet the demands of an external crisis. Instead, he was forced to counteract a new pattern of partisan behavior — nonstop congressional obstruction — with a partisan (and increasingly preemptive) approach of his own.

The result was an extraconstitutional arms race of sorts: a new normal that habitually circumvented the legislative process envisioned by the framers. Republicans provided a blueprint for future congressional minorities, demonstrating the possibilities and advantages of using procedural tricks to incapacitate a president they oppose. For his part, Obama drafted a playbook for future presidents to deploy in response: How to Get What You Want Even If Congress Won't Give It to You.

Now, a few years later, that’s the very playbook many of Obama’s would-be Democratic successors are promising to adopt — and expand. Visit any 2020 campaign website and you’ll see the usual list of utopian legislative proposals. But dig a little deeper, beyond the boilerplate, and you’ll find that when it comes to plans with an actual chance of being implemented, many rely heavily on executive authority.

California Sen. Kamala Harris is perhaps the best example. Last week, Harris announced that as president she will reinstate Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, which Trump has attempted to end. But she won’t stop there. In addition, Harris plans to make it easier for DACA recipients to apply for citizenship while extending the program’s protections to their parents and other law-abiding immigrants with strong community ties. Ultimately, Harris’s campaign estimates that such unilateral maneuvers would give 2 million immigrants a path to citizenship and protect up to 6 million from deportation — many times more than the hundreds of thousands affected by Obama’s order.

This would be the closest America has come in decades to wholesale immigration reform, and it would occur entirely through executive fiat.

“Sen. Harris is focused on tangible, direct action that helps people, especially in this era of congressional dysfunction and Republican obstruction,” campaign press secretary Ian Sams tells Yahoo News. “While she won't stop fighting to pass broad reforms, such as major middle-class tax cuts, rent relief and protection for reproductive rights, she will use every tool within her executive authority to bring about immediate change.”

Harris would take the same approach to gun control and wage equality. If Congress fails to pass gun legislation during her first 100 days in office, she has pledged to sign an executive order mandating background checks for customers of any dealer who sells more than five guns a year. To help close the gender pay gap, Harris would require federal contractors to show that they are paying men and women equally — and bar them from competing for federal contracts over $500,000 if they fall short.

By campaigning in advance on plans meant to circumvent future obstruction — as opposed to just responding to existing obstruction with executive workarounds — Harris is taking Obama’s “We Can’t Wait” strategy more literally than Obama himself did, building a popular mandate for an approach to presidential power that at least partially writes off congressional engagement from the get-go.

And she’s hardly alone. Julián Castro, the former mayor of San Antonio and secretary of housing and urban development, would get the government out of the business of routine immigration enforcement; likewise, former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke says he will issue a barrage of executive orders to radically restrict immigration enforcement. O’Rourke’s plans on LGBTQ rights and climate change also lean heavily on executive actions. Warren has pledged on her first day in office to sign an executive order “that says no more drilling — a total moratorium on all new fossil fuel leases, including for drilling offshore and on public lands.” New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker announced last month that he would “affirmatively advance reproductive rights and expand access to reproductive care” through executive actions, creating a White House Office of Reproductive Freedom in the process. And on Tuesday, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar went even further, unveiling a list of 100 executive actions she would take during her first 100 days in office — essentially transforming the president’s traditional “First 100 Days” legislative agenda into a wholly one-sided affair.

“After four years of Donald Trump, a new president can’t wait for a bunch of congressional hearings to act,” Klobuchar explained.

For now, the politics of presidential power are straightforward. Signaling that you expect Mitch McConnell to block your agenda and promising that you will amass as much power as possible to fight back is a popular position in the eyes of Democratic primary voters scarred by the unprecedented obstruction of the Obama era — which is why such pledges are playing a bigger role in the 2020 presidential campaign than ever before.

The issue of presidential power probably won’t hurt Democrats in the general election, either. Though Trump tweeted in 2014 that “Repubs must not allow Pres Obama to subvert the Constitution of the US for his own benefit & because he is unable to negotiate w/ Congress,” he has embraced executive action while in office, boasting on his 100th day that no president since World War II had signed as many executive orders by that point (even if many were essentially meaningless) and leaving acting secretaries in charge of major agencies to skirt the Senate confirmation process (even though his own party is in charge of the chamber).

But if a Democrat wins in 2020 — and starts to govern by going solo — all of that will change. Trump should serve as a warning here. During discussions about executive authority, Obama was known to worry about "leav[ing] a loaded weapon lying around”; his successor has since picked up that weapon and used it to blast holes in his legacy. Legislation may be difficult to pass, but it’s also difficult to overturn. Executive maneuvers are the opposite. All it takes to undo them is a president who disagrees with your politics, and Trump has taken advantage, using executive actions and cabinet-level agency decisions to reverse fragile Obama accomplishments on climate change, LGBTQ rights, labor standards, health care and immigration. Even where he’s been stymied by the courts, as with DACA, the resulting uncertainty still serves to undermine the protections Obama unilaterally put in place.

Beyond the absurdity of reducing America’s entire governing process to successive presidents simply erasing each other’s achievements with the stroke of a pen, Democrats should also worry where escalation could lead. Imagine that Warren wins the presidency. The Massachusetts senator hasn’t made executive action a centerpiece of her campaign the way her counterpart from California has. But as the only candidate who has created a federal agency from scratch (the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau), she is unusually familiar with the inner workings of the regulatory state; as president, her campaign tells Yahoo News, she would aggressively advance her agenda on education, the environment and the economy by appointing like-minded regulators and enforcing regulations that previous administrations have overlooked. At the same time, Warren has vowed to push her party to end the legislative filibuster if Democrats win control of the Senate and McConnell continues to “block things the way he did during the Obama administration.”

If that scenario does come to pass — a big if, given how many Senate Democrats still publicly support the filibuster, but one worth considering — Washington would descend into the unknown. Accompanied by regulatory changes, the president’s legislative agenda might sail through on a series of party-line, simple-majority votes, but the increasingly conservative judiciary could push back, leaving the country rudderless. “I can imagine a lot of these judges — most of whom are favorably disposed toward executive power — deciding things are a little different with a Democratic president in charge,” says Norm Ornstein. “So you could start to see these actions and laws being reversed by the Supreme Court.”

Democrats, in turn, could respond by pushing some of the big, self-serving structural reforms they’ve been floating this year on the trail: abolishing the Electoral College; granting statehood to Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.; adding justices to the Supreme Court.

It would be a constitutional clash of epic proportions.

“Once you start down the path of expanding presidential authority — or continue down that path, or pave new lanes for that path — you're creating more opportunities for imbalances of power and abuses of power,” Ornstein says. “We’d be in a place dark enough that it would not be at all clear we'd be able to avoid serious unintended consequences. It would be a transformation of the system in a fundamental way.”

Which is exactly what Biden, for one, has worried about all along. Back in 2011, as various White House advisers grumbled about congressional obstruction, the 36-year Senate veteran suddenly piped up to remind Obama's team that whatever they did next, they had to do it in a way that preserved the integrity of the White House, Congress and the relationship between them.

"My concern is about the American people losing faith in government," Biden said. "We have to avoid that possibility at all costs."

He’s still saying the same thing today.

“If you can’t get a consensus, guess what?” Biden fumed last week. “Power flows to the president. An abuse of power takes place. … We’ve got to put the guardrails back up. … The idea that we’re going to come along and do the same thing [Trump] did? Not on my watch! We just fight it out, man. … That’s not who we are. That’s not America.”

Democrats aren’t wrong when they say Republicans started this fight. But in figuring out how to respond in 2020, they may have decide which is riskier: a president who spins his or her wheels trying to work with Senate Republicans — or one who veers off into uncharted territory, leaving Congress behind.

Read more from Yahoo News: