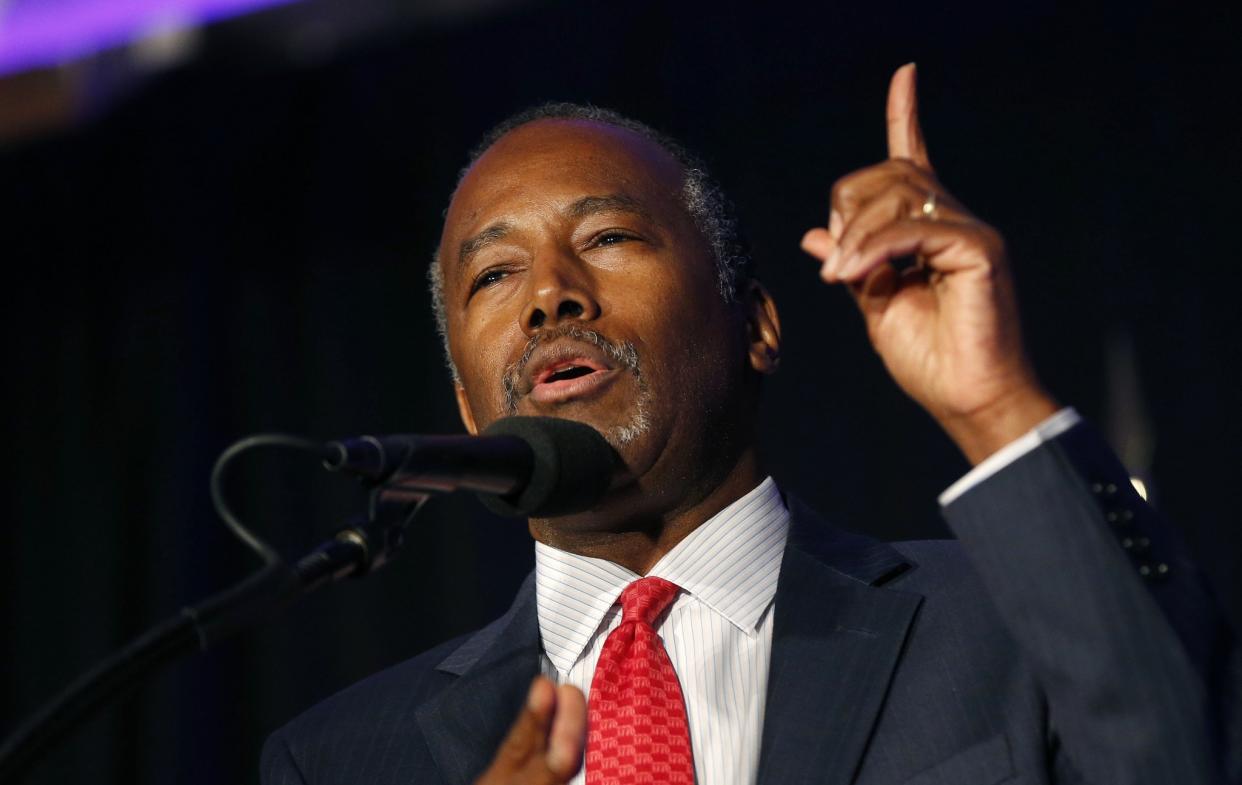

Ben Carson called new housing laws ‘social engineering.’ That worries fair housing advocates.

In one of his few public statements on the subject of affordable housing prior to being picked to run the federal agency in charge of that housing, Dr. Ben Carson called such programs “social engineering.”

It is a view that worries longtime housing advocates who find themselves parsing the limited words Dr. Carson has spoken and written on the subject before the former neurosurgeon was named Monday Donald Trump’s choice for secretary of housing and urban development.

“The fair housing community has been hoping for a HUD appointee that would do no harm,” said Erin Kemple, executive director of the Connecticut Fair Housing Center. “Someone who would not try to dismantle the fair housing laws even if he didn’t actively enforce them. We still hope Ben Carson could be that person, but the few things he has said raise a lot of red flags.”

HUD, with its $47 billion budget, is tasked with helping five million families find rentals they can afford and with helping homeowners who are threatened with foreclosure. Under the Fair Housing Act of 1965, that mission technically includes insuring equal access to housing regardless of race, but the history of the agency is inconsistent in terms of implementing that legislation.

Under some administrations the agency was proactive against discrimination. In 1973, for instance, HUD partnered with the Justice Department to sue Trump’s father, Fred, under the act, charging that blacks who applied to be tenants in his buildings were told no apartments were available, while whites were welcomed.

Seven years later, in contrast, HUD was the defendant in a lawsuit brought by the NAACP, who charged that it allowed the city of Yonkers to discriminate against residents of color by building nearly all its public housing in a ghetto-like cluster.

“Since 1969, HUD has been a vehicle — sometimes ineffectual, sometimes stalled, but still a vehicle — trying haltingly to get toward a vision of housing that is free of discrimination,” says Michael Sussman, the lawyer who successfully represented the NAACP in the Yonkers case. (Coincidentally, Judge Leonard B. Sand, whose ruling required Yonkers to build new housing in the white, middle-class side of town, died on Saturday, less than two days before Carson’s appointment was announced.) “Most recently, it has been a vehicle for good, but this appointment indicates a shift away from whatever optimism I might have felt in the past year.”

The recent progress of which Sussman speaks were two decisions during the summer of 2015 that housing advocates hailed as milestones. The first was from the Supreme Court, affirming “disparate impact” by ruling that municipalities can be found responsible for discrimination if the effects are separation of the races, even if that was not the intent. The second was a HUD decision known as “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing,” which put teeth into existing law by saying that to receive federal housing funds, local governments must prove they are working toward desegregation.

Those two decisions led to one of Carson’s few public stands on housing — an op-ed piece in the Washington Times in June 2015, criticizing both. Carson, then a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, wrote that the new standards would destroy wealthy neighborhoods by requiring they accept low-income housing, and also damage poorer neighborhoods by prohibiting funds from being spent to upgrade housing stock. He compared the policies to school busing plans of the 1970s, which resulted in white flight.

“These government-engineered attempts to legislate racial equality create consequences that often make matters worse,” he wrote. “There are reasonable ways to use housing policy to enhance the opportunities available to lower-income citizens, but based on the history of failed socialist experiments in this country, entrusting the government to get it right can prove downright dangerous.”

Soon after, in an interview with an Iowa radio station, Carson criticized an HUD agreement with the city of Dubuque that would provide more housing vouchers for African-Americans moving to the area from cities like Chicago. “This is just an example of what happens when we allow the government to infiltrate every part of our lives,” Carson said. “This is what you see in communist countries, where they have so many regulations encircling every aspect of your life that if you don’t agree with them, all they have to do is pull the noose. And this is what we’ve got now. Every month, dozens of regulations — business, industry, academia, every aspect of our lives — so that they can control you.”

Housing advocates yesterday said that Carson’s public statements reflect a misunderstanding of housing law. There is no requirement that affordable housing be placed in wealthy residential neighborhoods, they said, and most of what has been built has been aimed at mixed-income urban areas, where services like transportation and access to public health clinics already exist. Similarly, the history of housing policy shows that publicly sanctioned private “social engineering” efforts have been with America for as long as the country has existed. In the past century, that included efforts to steer people of color to certain neighborhoods, to allow for restrictive covenants on property deeds and to refuse mortgage loans and therefore home ownership to those in the inner cities.

As for the comparison to the white flight caused by school busing, Sussman responded: “Everyone doesn’t leave. We saw that in Yonkers; existing homeowners didn’t leave.” Carson’s seeming lack of knowledge of this history has deepened concerns about his lack of background in the housing sphere. On Monday, House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi called him a “disconcerting and disturbingly unqualified choice” with no “relevant experience” beside the fact that he lived in public housing during part of his childhood.

Sussman, for one, thinks the fact that Carson is a stranger to the field is his very appeal to the Trump administration. “At Education, at HHS, even the presidency itself, we’re in a world where the fact that you have no experience doing something is a great qualification. That’s really the message, especially when it comes to domestic policy.

“There’s no history that needs to be known,” he continued. “No institutional history that matters. What you are saying to people who spent their whole lives in those areas is, ‘Your whole life, what you know, what you’ve learned, means nothing.’ They would like to undo 40 years of social policy.”