Beto O’Rourke, on a ‘suicide mission’ against Ted Cruz, is having the time of his life — and might even come out of it alive

HUTCHINS, Texas — Beto O’Rourke was trying hard to play it cool, but finally, he just couldn’t resist.

“I have to show you this,” the Democratic congressman from El Paso, Texas, said, reaching into his pocket to grab his iPhone, where he began scrolling through text messages. “Sorry, I’m so excited about it.”

It was shortly after noon on a recent Saturday, and O’Rourke, or simply “Beto” as voters here have come to know him, had been going since around dawn in what Republicans and even some Democrats here once described as a “suicide mission” to unseat the state’s junior senator, Ted Cruz.

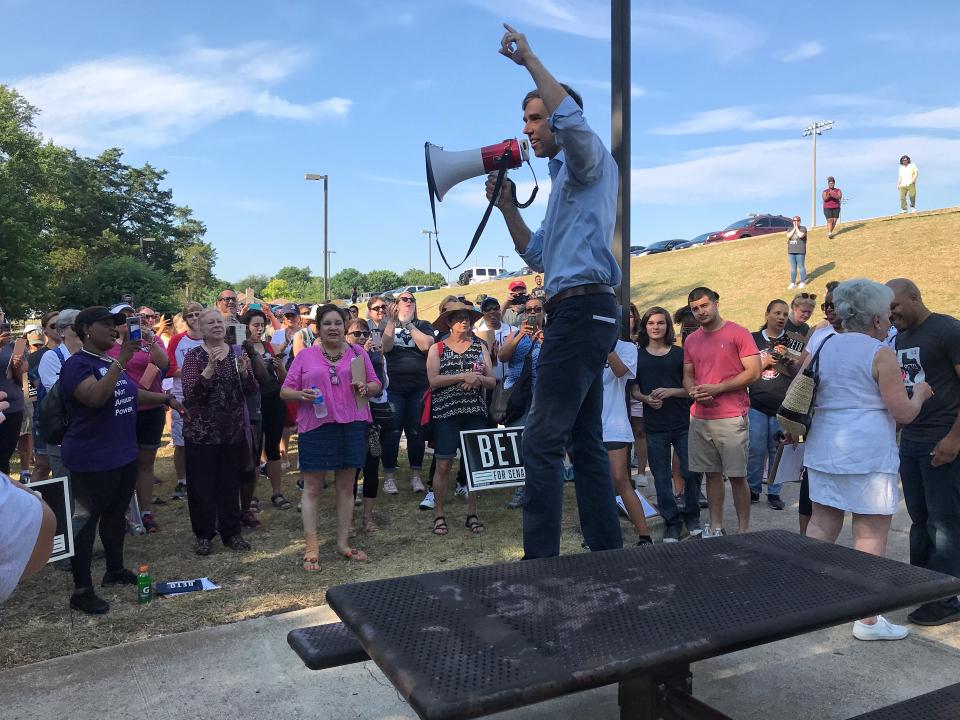

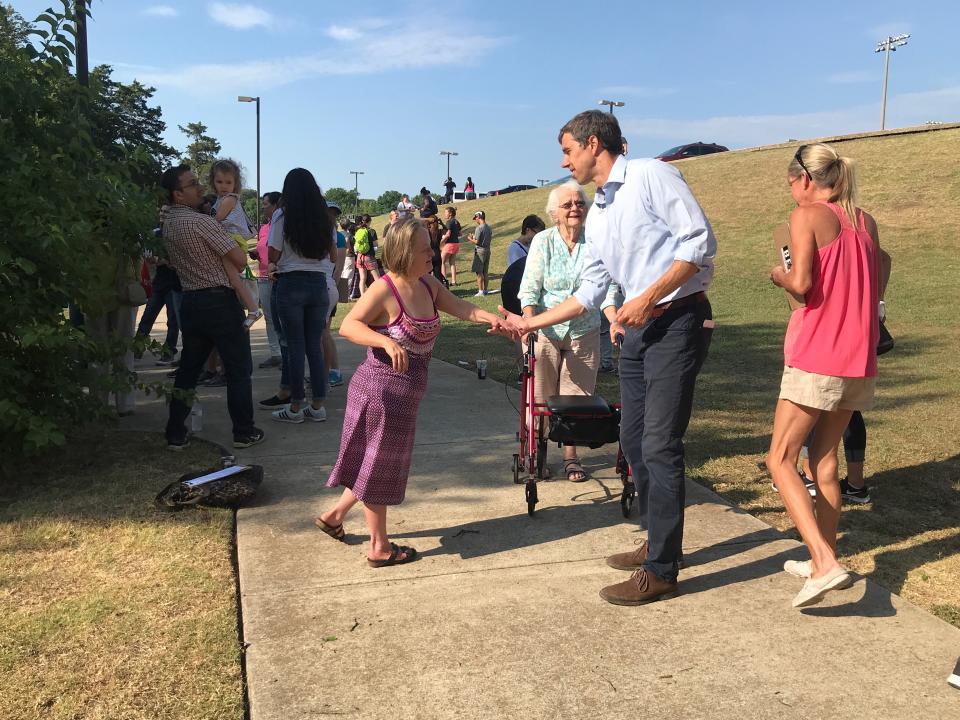

He had just wrapped up his fourth stop of the day — a town hall in this small suburb south of Dallas, where he had addressed about 150 people, including an African-American woman who had stood and invoked Nelson Mandela to describe his unlikely quest as an unabashedly liberal Democrat to replace a Tea Party Republican in Texas. “They always said it was impossible until it got done,” the woman said, paraphrasing the legendary South African leader. Addressing the congressman, she said, “You’re about to do it.”

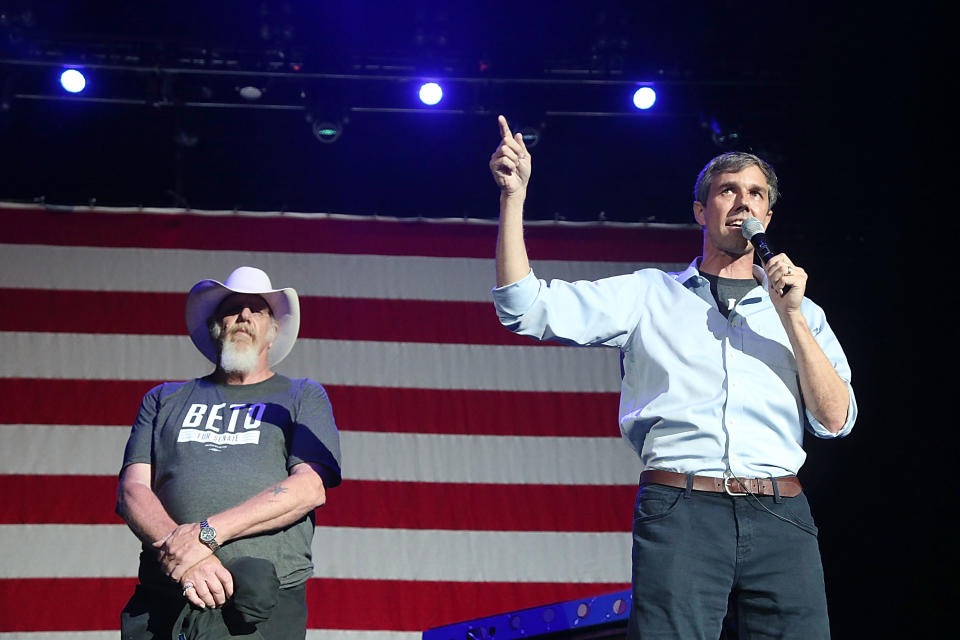

It was the kind of thing that people have been saying to O’Rourke, a lanky 6-foot-4 lawmaker whose undeniable charisma on the stump has invoked steady comparisons to a young Barack Obama by Democrats in search of their next great hope. A year ago, most people here had never heard of the 45-year-old, three-term congressman. But now, he was famous enough that a few days earlier, O’Rourke had found himself onstage strumming a guitar next to Willie Nelson — “THE Willie Nelson,” he said incredulously — at the singer’s annual Fourth of July picnic in Austin.

It was a turn of events that O’Rourke, who once toured the country playing bass in a punk band, still seemed a little stunned by. Showing a reporter a photo of him onstage with Nelson, he almost seemed to be reminding himself that it had really happened. O’Rourke, along with the singer Margo Price and Ray Benson, the legendary frontman from Asleep at the Wheel who had worn a “Beto” shirt onstage, joined Nelson for a medley of hits, including his pro-pot anthem, “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die.” And afterward, he had been given the stage to make his pitch to several thousand fans.

“I mean, that’s just f***ing amazing,” O’Rourke said. In the image, he stood next to Nelson with a look of concentration as he picked at a shiny Fender acoustic. Dressed in well-worn jeans and a gray T-shirt reading “I Love You El Paso,” he looked more like an aging hipster than a political candidate.

“That was so cool,” O’Rourke said, enthusiastically. “I grew up with Willie Nelson in the tape deck. I feel like the luckiest guy in the world.”

O’Rourke’s eagerness to show off his cool cred to a reporter could seem calculating. Any politician in a state full of trucks sporting bumper stickers like “In Willie We Trust” would be smart to saddle up to man considered one of the godfathers of the Texas music scene, even if they didn’t entirely approve of his pot-smoking hippie ways. (O’Rourke and Nelson are kindred spirits in at least one way: They both want to legalize marijuana.) But scrolling through the photos and pointing out Nelson’s bandmates, including Mickey Raphael — “The best harmonica player in the world! Also from El Paso!” — O’Rourke came across as genuine, someone who really was dumbstruck by the moment. That quality is part of what makes him such an effective campaigner: the ease with which he can actually seem human.

That could be a winning asset in a race against Cruz, whose shortcoming as a candidate has been his aloof stiffness — something he has been working mightily this year to overcome.

Nelson didn’t formally endorse O’Rourke that evening, but he didn’t have to: the picture of them together is worth a thousand words, or a thousand TV spots, for a congressman whose reputation as a rising Democratic star has made the race, once considered a lock for Cruz, suddenly competitive in the final stretch before Election Day.

But are that celebrity and attention enough to help O’Rourke win in a state where no Democrat has won statewide office since 1994, and which last elected a Democrat to the Senate — Lloyd Bentsen, one of the most conservative members of the caucus — in 1988. But O’Rourke takes heart from the state’s increasing diversity and growing signs of disenchantment with Donald Trump, even among some Republicans. Trump is still popular, but not as popular as you might expect in a state widely regarded as one of the most conservative. A Quinnipiac poll released earlier this month found 49 percent of likely Texas voters disapproved of his job performance, compared to 46 percent who approved, a statistical tie.

Although Trump isn’t on the ballot, Cruz is — and having bound himself to the president after their bitter fight for the 2016 nomination, he’s battling his own issues with voters, who generally approve of the job he’s doing but don’t necessarily like him. Cruz has seen his lead shrink in recent weeks amid a series of bad headlines for Republicans, including about the Trump administration’s forced separation of migrant kids and their parents. The same Quinnipiac poll found Cruz leading O’Rourke by just 6 points, down from the 11-point lead he held in May, and even though the Cruz campaign insists its internal polling is better than public surveys, the Republican has been openly nervous, acknowledging the race will likely be close and urging supporters not to be complacent heading into Election Day.

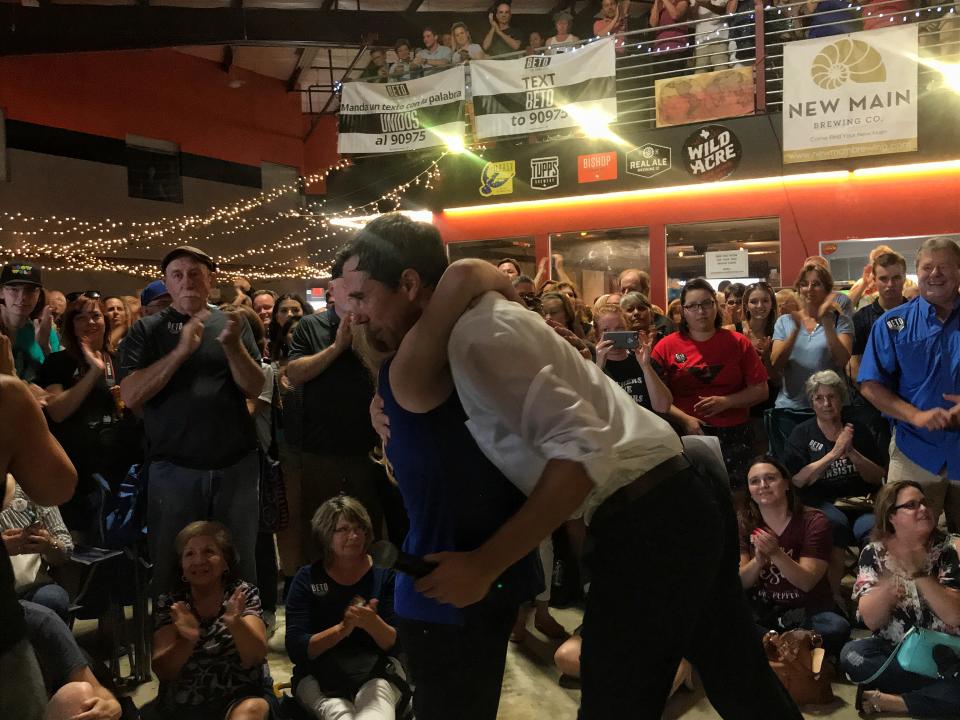

What has Cruz on guard is O’Rourke’s indisputable star power. His town halls, especially in some cities, have some of the qualities of a rock concert. Voters shriek for his attention and shove one another as they rush to grab his hand. At an event in Farmers Branch, a suburb of about 30,000 people north of Dallas, the fire marshal shut the doors on scores of supporters because the room was already at capacity before O’Rourke had arrived, bringing one fan to the point of tears. “But I have a seat,” she pleaded in a near panic. “I signed up online!”

When a woman collapsed at packed town hall near Fort Worth after waiting hours to see O’Rourke in the oppressive heat — something that has happened more than once — the congressman planted himself on the ground next to her, taking her questions and making his pitch as they waited for an ambulance to arrive.

In a post-2016 political environment in which no single figure has emerged to capture the hearts and imaginations of Democrats eager to see their party rise out of the Trumpian wilderness, O’Rourke is increasingly being seen as the party’s next big thing, both in and outside of Texas.

The media has helped. He’s been the subject of at least a dozen national profiles — including in Time, Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone and, most recently, the high society glossy Town & Country. Almost all have commented on the congressman’s uncanny resemblance to Bobby Kennedy — both in his relentlessly hopeful campaign message and his looks, the mop of floppy brown hair streaked with gray and toothy grin. Rep. Joe Kennedy, the Massachusetts Democrat and grandson of Bobby Kennedy who happens to be a close friend, has joked that O’Rourke is the “best looking Kennedy in Washington.”

His uphill campaign to turn Texas blue has also gotten a boost from Hollywood. The comedians Chelsea Handler and Rosie O’Donnell and actress Sophia Bush have championed O’Rourke on social media. Sarah Jessica Parker wore a “Beto” pin to the Tribeca Film Festival, which was duly noted on the O’Rourke campaign website. And a recent campaign swing through Los Angeles netted large checks from the Hollywood glitterati, including “Star Wars” director Rian Johnson and actress Connie Britton.

Earlier this month, Sen. Kamala Harris, the high-profile California Democrat, sent a fundraising appeal on O’Rourke’s behalf, putting Texas on the map for national Democrats. But he was doing fine already. O’Rourke, who has pledged not to take money from political action committees, has raised more this cycle — $23 million — than any other Senate candidate in the country, Democrat or Republican, and nearly twice as much as Cruz.

More than $10 million was raised in the last three months alone, and a little over 40 percent of it was small contributions of $200 or less. As of June 30, O’Rourke had roughly $14 million on hand, compared to Cruz’s $10 million. That’s still not a lot of money for a campaign in Texas, where a statewide television ad buy costs at least $1 million a week. But last weekend, O’Rourke proved he could turn the money spigots on when he needs to — raising nearly $1.3 million in a little over two days, almost all from small donors, to fund his first television ad, which his campaign said will begin airing this week in all 20 of the state’s media markets. The spot is composed entirely of footage that O’Rourke and his staff had recorded on their smartphones last year.

Cruz regularly calls attention to the “millions in free media” his opponent has received. The day after O’Rourke’s appearance with Nelson, the Republican senator mocked his opponent as the darling of “Hollywood celebrities” and “far-left liberals” who have tried for years to turn Texas blue. “National liberals, folks in the media, their hearts go pitter-pat at Congressman O’Rourke because he is running hard left,” Cruz said in an interview. All that attention, he said, was “great for raising lots of money … and for getting onstage and jamming with Willie Nelson. But that doesn’t reflect the common sense values of Texas.”

But O’Rourke’s ability to raise big sums from small donors, who he can tap again before November, has alarmed Texas Republicans who are fighting to retain the party’s hold not just on Cruz’s seat, but also up and down the ballot, including congressional races where Democrats have mounted surprising challenges.

With Gov. Greg Abbott holding a wide lead over his Democratic challenger, former Dallas County Sheriff Lupe Valdez, Republicans are worried that some conservatives might not bother to vote and that Democrats, energized by O’Rourke and the potential of a blue wave election nationally, could turn out in historic numbers.

A veteran Republican strategist in the state described O’Rourke as “the most promising political underdog” he had seen in Texas since, well, Ted Cruz. Six years ago, it was a largely unknown Cruz who rode a wave of grassroots support and money and relentless media attention to defeat David Dewhurst, the state’s millionaire lieutenant governor and establishment favorite, in the GOP primary. O’Rourke, the strategist said, appears to be attracting the same kind of energy that fueled Cruz’s rise. But, he quickly added, “That doesn’t mean he’ll win.”

Indeed, Democrats have been down this road before, getting excited about a would-be party savior who falls short. It happened four years ago when state Sen. Wendy Davis, famous for her 2013 filibuster of an anti-abortion bill and the pink running shoes she wore to stand and speak for 13 hours, ran for governor and drew the same kind of national attention that O’Rourke has been getting, including celebrity endorsements and glowing media profiles.

Despite the hype, Davis lost by 20 points to Abbott, demonstrating the axiom that if all the Texans who identify as conservative turn out, Republicans win. It was one of the state Democratic Party’s worst losses in a gubernatorial race in decades, and many despondent Dems began to wonder if their party would ever recover.

But the party didn’t give up. Political operatives from the Obama campaign banded together as “Battleground Texas” to brainstorm on strategies. They believed they would be helped by the changing demographics, including a growing Hispanic population and an influx of new residents from more liberal locales like California that was turning the biggest cities — Dallas, Houston and Austin — blue.

One focus was turning out new voters, especially Latinos. Texas added 1.5 million Latino residents between 2010 and 2016, fueling an undercurrent of optimism among Democrats. But many of the new residents didn’t vote — turnout averaged around 30 percent among Hispanics in 2012 and 2014 — and those who did vote didn’t necessarily support Democrats. In 2012, Cruz, a Cuban American, won 40 percent of the Hispanic vote in Texas. And though narrowing polls in 2016 sparked hope that Latino turnout might be enough to help Hillary Clinton win Texas, Trump still won, although his margin — 700,000 votes, or about 9 points — was the smallest of any Republican presidential candidate since 1996.

But O’Rourke saw something in the results that others missed. He believed Democrats were so focused on trying to turn out voters in big cities that they had basically ceded wide swaths of rural Texas to Republicans. Sure, most of those counties were bright red, and had been for decades, but what if a Democrat were to campaign in these towns, to appeal to the kind of “forgotten Americans” that Trump often invoked, many of whom had never even been visited by a political candidate, Republican or Democrat, from outside the area.

O’Rourke has not been shy about trashing his own party for “giving up” small-town Texas, repeatedly describing it to reporters and voters as one of the “dumbest” things that Democrats in the state have done. “We Democrats conceded the ground to [Republicans], literally the physical ground, the geography, the Panhandle, north Texas, east Texas, small-town west Texas,” O’Rourke told the Ringer last year. “We just said, it’s yours, take it, we’re not gonna even compete. We won’t even show up … You win by default. I don’t know why.”

But O’Rourke’s diagnosis largely fell on deaf ears — mainly because few people in Texas, even his fellow Democrats, even knew who he was. Though he began his political career more than a decade ago, winning a seat on the El Paso City Council, he was a virtual unknown in Texas and in Washington until he launched his race for Senate last year.

O’Rourke’s life story is not a subject that comes up very often on the campaign trail — perhaps because it’s not an inspirational tale like the one that Cruz tells about his father, who fled Cuba for America with $100 sewn in his underwear, looking for a better life.

He was born Robert Francis O’Rourke and called “Beto,” the Spanish nickname for Robert, from infancy to distinguish him from his grandfather, also named Robert. Though he speaks fluent Spanish, he is Irish-American. His family was well-to-do and politically active with deep roots in El Paso. His father, Pat O’Rourke, who died in 2001, was a lawyer and real estate developer who spent time as a county judge. His mother, Melissa O’Rourke, whom O’Rourke often mentions to voters is a Republican, ran her family’s high-end furniture store and is now in real estate.

As a kid, O’Rourke yearned to escape from El Paso, and soon he did. Though he often mentions to voters that he attended El Paso High, he graduated from an all-male boarding school in Virginia and went to Columbia University, graduating in 1995 with a degree in English literature. But in a piece of biography that he often does mention, O’Rourke spent his school breaks touring the country playing bass with a punk band, Foss, that he founded with El Paso friends.

After college, O’Rourke stayed in New York, living with his band in a factory loft in Brooklyn that they converted themselves. The neighborhood, Williamsburg, was grittier than the polished hipster mecca it has become. He thought he wanted to be a writer or work at a publishing house, but soon, he felt drawn back to El Paso, the city he once rejected but now missed.

El Paso then was trying to reinvent itself after losing thousands of jobs when major employers like Levi Strauss and other manufacturers relocated their plants across the border after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). (An early critic because of the negative impact on his hometown, the congressman now opposes Trump’s efforts undo NAFTA, arguing El Paso and other communities in Texas that have adapted to the new economic reality would have to adjust all over again.)

Back home, O’Rourke launched an online alternative weekly covering the city’s politics and culture, and he founded Stanton Street, an internet services and design company. (The company, which still operates under different ownership, helped design O’Rourke’s minimalist black-and-white campaign signage and web presence.)

In 2005, O’Rourke married Amy Sanders, a charter school administrator, and made his first foray into politics, winning a City Council race in an upset. He served for six years, championing downtown redevelopment and encouraging cross-border relations with Ciudad Juárez, just across the river. Presaging the progressive platform he runs on today, O’Rourke made headlines across Texas in early 2009, when he offered up a purely symbolic measure calling for “an open national debate” on ending the war on drugs, which he said would halt cartel-related violence along the border.

Among those who mocked him for the measure was Rep. Silvestre Reyes, an influential Mexican-American congressman who had represented the El Paso area for more than a decade. In 2012, O’Rourke would defy his own party to challenge Reyes in what became an ugly campaign pitting the young progressive against the state’s Democratic establishment and national Dems like Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. But O’Rourke won the nomination and went on to Congress, where he has served three terms, mostly unremarkably save for his occasional clashes with party leadership.

He was among a handful of Democrats who mounted a failed challenge to replace party leader Nancy Pelosi in 2014 and voted against her two years later. As a Senate candidate, he has criticized both Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer as subservient to wealthy donors. He has called the political system in Washington “rigged” and has introduced legislation to impose congressional term limits, arguing it’s the only way for lawmakers to avoid corruption. Although his views tend to align with those of Bernie Sanders, O’Rourke stayed on the sidelines of the 2016 Democratic primary and waited until late in the campaign to formally back Clinton.

So perhaps it was no surprise that O’Rourke didn’t consult any party leaders in Texas or in Washington last year when he first considered running for Senate. Instead, he began traveling to some of those small towns he believed had been left behind, sounding out voters on whether they thought a Democrat could win.

One of the few Texas Dems he did engage was Davis, whom he quizzed about what she had learned from her own failed campaign. She told him to blow off high-price consultants, especially people not from Texas, and to listen to his gut. Like him, she believed winning would require more than turning out Democrats and flipping some moderate Republicans, but looking beyond party strongholds to appeal to disengaged Texans who had maybe never cast a ballot in their lives.

“Running in Texas is a daunting task because it’s almost like running nationwide. It’s such a big place, and within it, it’s like a lot of little mini-states, each with its own personality, each with its own voting demographic, each with its own unique concerns, and you need to be able to speak all of that,” Davis said.

The congressman has not spent his war chest on the trappings of a traditional campaign. As O’Rourke often points out to reporters, he doesn’t have a pollster and is serving as his own political strategist. And those he has hired are largely fresh faces. His campaign manager, Jody Casey, was hired last year after working nearly 18 years at General Electric in El Paso, mostly in sales. She has never run a statewide political campaign.

O’Rourke has paid $4.7 million to Revolution Messaging, the progressive ad agency behind Sanders’s presidential campaign, for digital ads — the largest area of expenditure of his campaign so far. But he has said he will skip the usual mechanics of statewide campaigns — like fancy mailers and widespread television and radio advertising. Instead, he plans to spend heavily on ground operations in the state to help his campaign connect with and turn out voters. Although the campaign says it already has a robust field operation in place, over 30 offices, his recent campaign finance reports suggest he runs a bare-bones campaign operation staffed largely with volunteers.

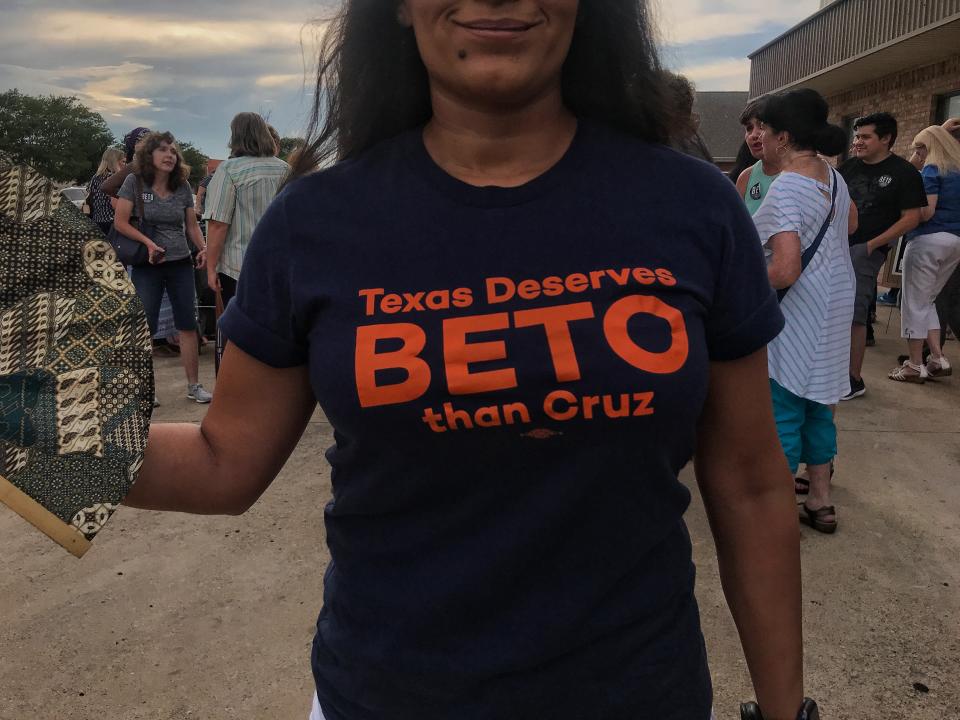

Around the state, some of his supporters have set up field offices entirely on their own, including a woman in Longview, an old oil town in East Texas where Democrats don’t typically compete.The O’Rourke’s campaign pays the rent, and volunteers have found the locations and run the day-to-day outreach to voters. When Cruz campaigned in the city last month, greeting local residents at a burger joint, a handful of O’Rourke backers showed up, wearing “Beto” T-shirts and waving signs in a show of support they said was coordinated locally by volunteers and not O’Rourke’s El Paso campaign office. Earlier this month, when O’Rourke came to Longview for a town hall, more than 700 people showed up, a huge turnout for a town this size.

But Republicans, including Cruz, point out that big crowds don’t necessarily translate into votes. They cite the Democratic primary in March, which O’Rourke won with less than two-thirds of the statewide vote against a handful of even less-well-known opponents. O’Rourke, not unlike Davis in 2014, lost dozens of counties in the Rio Grande Valley near the border, a region dominated by Hispanic voters who should have been an easy win for the congressman who has staked out a position as one of the biggest critics of the Trump administration’s immigration policies.

Republicans have argued it’s a sign of trouble for O’Rourke’s campaign. They have doubled down on their own attempts to flip the region by tailoring appeals to Catholic, anti-abortion Latino voters and to small-business owners who have benefited from the Trump tax cuts backed by Cruz.

But political observers, including at the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas, pointed out that across the state O’Rourke turned out a record number of voters for a Democrat. A Democratic operative told the Texas Observer he suspected the political machine in south Texas, where workers known locally as politiqueras expect to be paid to turn out voters (and have been arrested for election fraud and corruption while doing so), had intentionally tried to drive down O’Rourke’s numbers to teach him a lesson because he hadn’t hired them.

O’Rourke said he needed to do a better job at winning over Hispanics. And he has returned to the region repeatedly in his endless crisscrossing of the state. In a rarity for a Democrat and even a Republican seeking statewide office, O’Rourke has traveled to all 254 counties. Cruz, by contrast, has “barnstormed every county in Iowa,” O’Rourke jibed at a rally outside Arlington, calling attention to the fact that Cruz began running for president just a couple of years into his first term, which didn’t sit well with some Texans.

Davis, who now runs a political nonprofit in Fort Worth, has watched O’Rourke’s rise with interest and thinks he has a better shot than she did four years ago in what turned out to be a Republican-wave election. “He’s running in a far better climate than I was,” Davis said. It’s still going to be hard for a Democrat to win, she added. “But who knows? Lightning might strike.”

With fewer than 90 days to go before Election Day, O’Rourke’s main strategy has been to campaign relentlessly, everywhere. He has visited every corner of the state, and in recent months, has begun looping back. With an average of four or five stops everyday, at least, he sometimes drives hundreds of miles in a single day in a rented minivan, often accompanied by just two young staffers— Chris Evans, a millennial who serves as his communications director, and Cynthia Cano, his events and logistics coordinator who was previously O’Rourke’s congressional district director.

All three are regular characters in O’Rourke’s ongoing social media campaign, on platforms like Facebook Live, which lends his upstart campaign an almost “Truman Show” quality and, more importantly, free, unlimited advertising. He live-streams almost all of his political events, including town halls, small meet-and-greets and even encounters with individual voters as he goes door to door. His Facebook page has more than 100 archived videos of his interactions with voters. He streams even the most mundane events of his day, like the long drives between campaign stops, where the congressman, who is generally behind the wheel, talks to whoever might be watching, occasionally shouting expletives at his GPS, and takes questions.

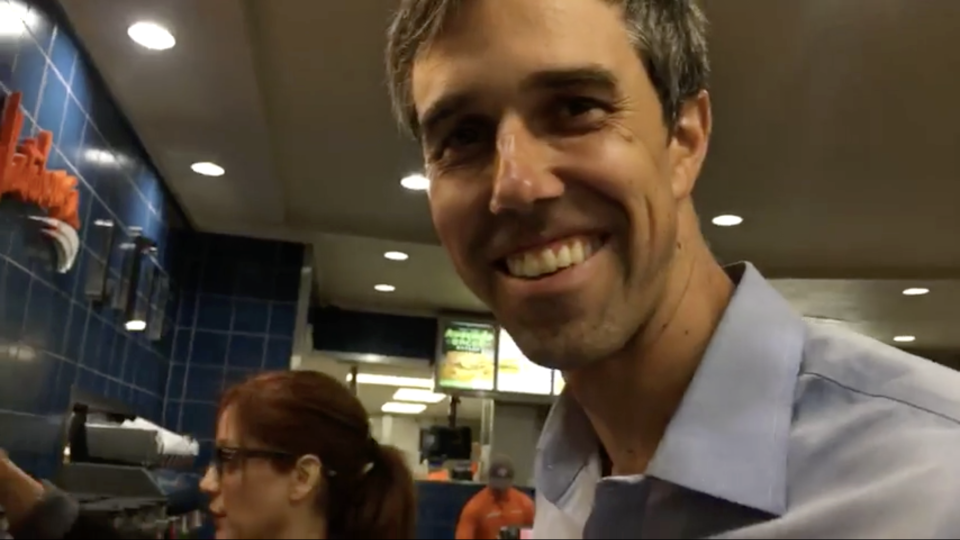

More than 46,000 people watched O’Rourke’s late-night visit to a Whataburger in Corpus Christi a few days ago. Whataburger is a favorite destination for the congressman who, like a certain Republican president, favors greasy fast food on the campaign trail. Although supporters often leave messages on the videos worrying about O’Rourke’s diet and urging him to eat more healthy fare, the rail-thin candidate seems to burn off the calories with his frenetic campaigning.

At an appearance in Arlington, Texas, last month, O’Rourke was mobbed as he bounded through the door of a local brewery, leaping up as if he were making invisible three-pointers to greet the several hundred supporters filling the room. Even when taking questions from the audience, O’Rourke is an attentive listener, but he often struggles to stand still. His campaign recently added a series of political/physical endurance events to his schedule of events, including “Run with Beto,” where he jogs 3 or 4 miles with supporters, pausing in the middle to deliver his campaign spiel and take questions, and “Biking with Beto,” the same thing, except on bikes.

He is charismatic on the stump, delivering speeches more soaring and aspirational than detailed, and in the mainstream of progressive Democratic politics. In Arlington, he said the country needs universal health care. Teachers deserve a living wage. There should be equity in public schools, allowing all kids no matter their skin color to get a good education. Women deserve access to reproductive health services. Assault-style weapons should be banned.

But the controversy over the Trump administration’s handling of migrant parents and their children thrust him into the spotlight and has added a moral clarity to his message that could play well even in even in a state where most voters support tougher immigration laws. Although he has long opposed Trump’s proposed border wall, insisting there shouldn’t be that kind of barrier between two friendly countries, he went further in calling the child separations “torture” and “un-American.”

He has appealed to voters to consider their better angels — because even though this was the policy carried out by Trump administration, the decision was made in the name of United States. “We own this,” O’Rourke told the crowd in Arlington. “This is moment of truth to decide. We know it’s inhumane. We know that it’s cruel. It’s up to us to decide … if this is American or not,” he said.

“Every human life has value. We’ve got to start treating each other like human beings. We’re not animals. We’re not an infestation. We’re not something to be walled off or separated. We are not to be afraid of one another.”

Cruz has attacked O’Rourke for his liberal approach to immigration, accusing his opponent of favoring open borders and supporting the abolition of the Immigration Customs and Enforcement agency, known as ICE. (Under pressure from his own base, O’Rourke said in June that he was open to the idea of abolishing the agency but later dialed it back to suggest he would “abolish the practices” of ICE.) Cruz called it “a radical proposition” and seemed to throw the congressman’s suggestion that child separations were “un-American” back at him. “That may be popular with Democratic voters and radical activists,” he said of O’Rourke’s views. “But that’s not Texas, that’s not America, that’s not what we believe.”

On the stump, O’Rourke treads carefully in discussing Cruz. While he readily brings up Trump, he typically barely mentions Cruz by name unless a voter brings up the senator first. That has disappointed some of his supporters who want to see a more aggressive approach. At recent stops, some backers have pressed O’Rourke about his reluctance to go on attack.

“I’m not running against that guy. I’m not running against the president of the United States,” O’Rourke told voters at the town hall in Hutchins. “I’m running for Texas. I’m running for this country.”

O’Rourke seems intent on staying “focused on the prize — the big, ambitious, aspirational goals.” Another possible reason for holding his fire on Cruz is that he’ll need some Republican votes in the fall. But the congressman insists his talk about trying to rise above political dueling is more than a tactic. He genuinely bemoans the political polarization that has left Washington at a standstill.

“We’ve got to come together for the sake of the country,” he says. “I want to campaign that way. I want to serve in that way. You’ll never hear me badmouth another party. I won’t badmouth the sitting junior U.S. senator. This has got to be what we’re for, not who were are against.”

O’Rourke’s pledge to stay positive and aspirational in the race will undoubtedly be tested as he prepares to meet his opponent on the debate stage, where Cruz has a reputation as a skillful, take-no-prisoners debater. And it will also be tested by the growing interest of national Democrats in the race.

Democrats need just two additional seats to regain majority control of the Senate, and if the Texas race remains as competitive as it is today, party officials are unlikely to remain as hands off as they have been. That has given O’Rourke the freedom to chart his own course and keep his distance from the rest of the party, in the rest of Texas as well as Washington. It has not gone unnoticed that O’Rourke has skipped joint campaign events with Valdez and others on the state ticket, who would love for some of his star power to rub off on them.

O’Rourke comes across as protective of his brand and his independence, well aware that Texans do not react well to advice from outsiders. He is equivocal about his own growing celebrity, welcoming the media attention and the celebrity backers, but wary of seeming to enjoy it too much.

Asked about how he feels about the comparisons to Kennedy and Obama, O’Rourke paused for a few seconds. “I guess on some level, that’s flattering,” he said. But to him, it didn’t “line up.” They were extraordinary politicians who inspired generations of people to public service. He was just a regular guy running for Senate in Texas. “There’s no way I could be like either one of them,” he said.

But some of his supporters have bigger things in mind for him, looking beyond November. In Arlington, O’Rourke wrapped up his stump speech, as he often does, by appealing to people’s sense of virtue. What will you tell your kids you were doing in 2018 “when they were gonna build a 2,000-mile wall, when they were gonna ban all Muslims, when the press were the enemy of the people,” he said. “You want to be able to answer them: We won this f***ing election.”

The crowd erupted in wild applause. O’Rourke took questions. The first came from a man in his 20s. “My question is have you considered running for president?” he said. “Please? Please?”

The crowd erupted again in wild applause.

The man stood less than 4 feet away from the congressman and spoke his question clearly into a microphone. But O’Rourke pointedly dodged the question, pretending not to hear it or deliberately misinterpreting it.

“I think the question is about the consequences of somebody being the junior senator for Texas and running for president,” he said, reminding voters again that Cruz almost immediately began exploring a White House bid after joining the Senate. “With us, with this campaign, you will get a full-time senator for a full six years.”

Supporters clapped again, but not as enthusiastically.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: