Biden lost big in 2008. Is he a better candidate now?

A lot has changed since 2008. Has Joe Biden?

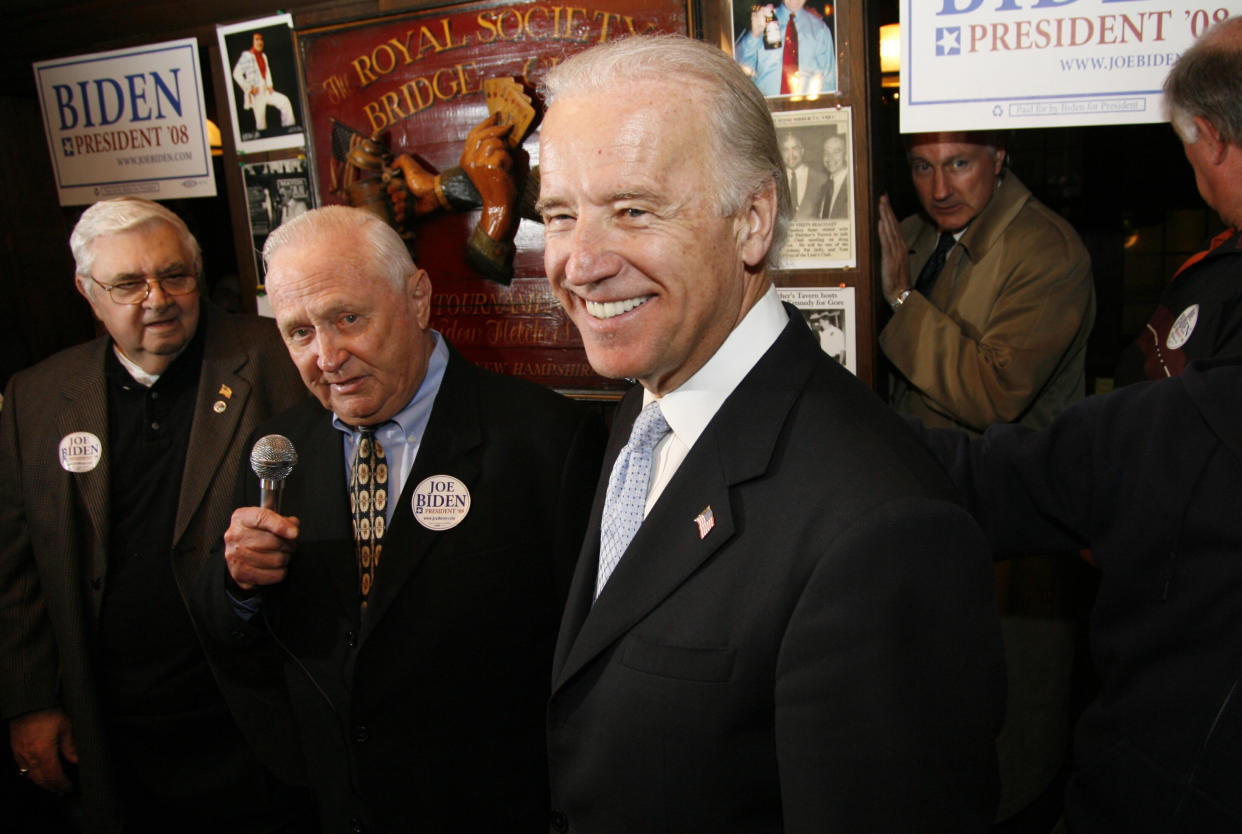

That was the year that Biden, then a six-term senator from Delaware, last ran for president. He launched his exploratory committee on Jan. 31, 2007, during a conference call marred by “loud echoes and a blaring television set.” He started out averaging about 3 percent in the polls; 11 months later, he finished fifth in the Iowa caucuses, with .9 percent of the state’s delegates. He dropped out that night.

“I ain’t going away,” he told supporters in Des Moines, with 14 teary-eyed relatives arrayed behind him.

Biden’s prediction came true. In August, Barack Obama tapped the senator as his running mate; Biden assumed the vice presidency the following January.

And now he’s running for president again.

On Thursday, Biden announced his much-anticipated third White House bid with a three-and-a-half-minute video excoriating President Trump as a “threat to this nation was unlike any I had ever seen in my lifetime.”

“I believe history will look back on four years of this president and all he embraces as an aberrant moment in time,” Biden said. “But if we give Donald Trump eight years in the White House, he will forever and fundamentally alter the character of this nation, who we are, and I cannot stand by and watch that happen.”

The immediate coverage focused on a few familiar episodes from Biden’s long Washington tenure, including his insensitive handling of the Anita Hill hearings and his humiliating first presidential campaign, in 1988, which ended shortly after he was caught borrowing too liberally from the speeches of British Labor Party leader Neil Kinnock, John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy, among others.

But nobody said much about 2008. At first glance, it’s easy to understand why. Today, as a widely admired former vice president, he is the closest thing to a Democratic favorite, with 98 percent name recognition, 75 percent favorability, and a substantial lead in the polls; whatever he says and does from now on will reshape the rest of the race.

Twelve years ago, however, Biden was the senior senator from the second-smallest state in the union — well-known on Capitol Hill, and in Delaware, and pretty much nowhere else. What could the two campaigns — one conducted as afterthought, the other as frontrunner — possibly have in common?

Yet more than any other chapter of his career, Biden’s 2008 bid previews what 2020 has in store for him. The hurdles ahead, it turns out, are surprisingly similar to the ones that tripped him up last time around — even if he’s grown in stature and standing since then. The question for Biden — the factor that will decide whether he finally wins his party’s nomination or again falls short — is whether he’s better prepared now to confront these challenges, or whether he remains the same old Joe.

The first day of Biden’s 2008 bid was also the worst day. If voters remember anything about Biden’s last presidential effort, it’s probably this: his description of Sen. Barack Obama, who had announced his own exploratory committee two weeks earlier, as “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.”

What people don’t remember is that he made the biggest mistake of his campaign before it had even officially begun.

Biden delivered his assessment of Obama in an interview with Jason Horowitz of the New York Observer. The two met over tomato soup in a diner 15 minutes from Biden’s Delaware Senate office, and, as usual, Biden did most of the talking — this time about the shortcomings of Obama, Hillary Clinton, and North Carolina Sen. John Edwards, his three main Democratic rivals.

Electing Clinton, he said, would lead to “nothing but disaster” in Iraq. Edwards doesn’t know “what the heck he is talking about.”

But it was Biden’s remark about Obama that got by far the most attention.

The interview appeared on the Observer’s website the morning of Wed., Jan. 31. By the time of his afternoon announcement call, it was all anybody could talk about. Biden spent the rest of his launch day explaining himself — how he had been “quoted accurately” but also taken “out of context”; how of course he didn’t mean that other African-Americans weren’t “clean” or “articulate”; how he “should have said ‘fresh’” instead.

At first, Obama shrugged it off, saying, “I don’t think he intended to offend,” even if “the way [Biden] constructed the statement was probably a little unfortunate.” But later that day, with Biden coming under fire from some black leaders, Obama issued a statement that approached a condemnation. “I didn’t take Sen. Biden’s comments personally, but obviously they were historically inaccurate,” he said. “African-American presidential candidates like Jesse Jackson, Shirley Chisholm, Carol Moseley Braun and Al Sharpton gave a voice to many important issues through their campaigns, and no one would call them inarticulate.”

“The staging of the kickoff for this presidential candidacy could hardly have gone worse,” wrote Adam Nagourney of the New York Times in a story headlined “Biden Unwraps ’08 Bid With an Oops!” “By the end of the day on Wednesday, Democrats were asking only half-jokingly whether Mr. Biden might be remembered for having the shortest-lived presidential campaign in the history of the Republic.”

Biden avoided that ignominy by continuing to campaign for another 12 months. But his bid never recovered.

In the years since, the Obama incident has come to represent yet another example of Biden’s “politically undisciplined” style (Nagourney’s words). Yet it was also more than that. This time around Biden is unlikely to self-destruct with a gaffe. Fresh off eight years of a Biden vice presidency, the entire country is already accustomed to his loose talk, and in the age of Donald Trump, few voters will dock him points for speaking in an unvarnished manner. It may even help him sound “authentic.”

The problem, in retrospect, is that his comments revealed his generational lack of ease with issues of identity and race. And while such issues used to play a relatively minor part in the nominating process, they’ve now become one of the Democratic electorate’s chief concerns.

As the Associated Press recently reported, white candidates in a Democratic field “celebrated for its historic racial and gender diversity” now face a “woke litmus test” that requires more than just favoring equality and civil rights. Today, the AP continued, white candidates must talk about “systemic racism and white privilege to connect with voters of color and prove that America’s racial divisions aren’t lost on them.”

“All candidates, especially non-ethnic minority candidates, need to be fluent in the issues that matter most to black America — police brutality, criminal justice reform, reparations, social justice,” said Democratic strategist Joel Payne, an alumnus of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

“Wokeness” wasn’t a thing the last time Biden ran for president. Now it is. Biden’s bid has already endured one flap over his well-meaning but occasionally unwelcome touching of women — an issue that wasn’t even mentioned in 2008 but that has led some Democrats to wonder, as New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg put it, whether “he is a product of his time” and “that time is up.” Another fumble could cement that perception.

Shifting mores aren’t the only stumbling block from Biden’s last bid that could vex him again in 2020. His message will continue to be a challenge as well.

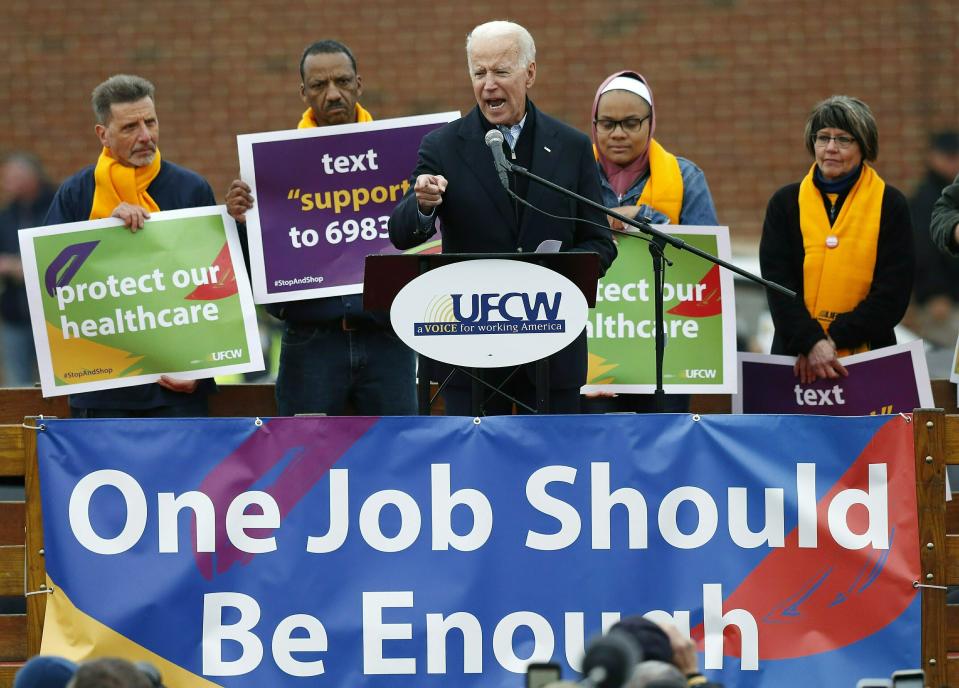

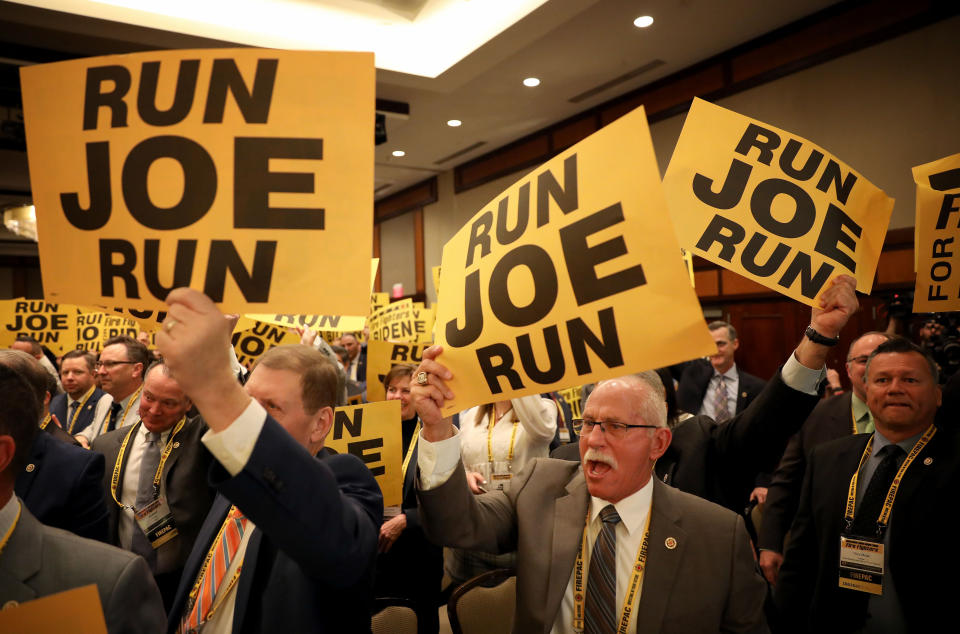

On Monday, Biden will formally kick off his campaign with a rally at a Pittsburgh union hall. His main idea? “Rebuilding an inclusive middle class.” During the 2018 midterms, he frequently recalled his blue-collar roots in Scranton, Pa., branding himself “Middle-Class Joe.” And in recent weeks he has joined a picket line of striking grocery store workers in Massachusetts and spoke to a firefighters union in Washington.

“Wall Street bankers and CEOs did not build America,” he said in Massachusetts. “You built America!”

It is, on the surface, a different theme than the one he chose in 2008. Back then, Biden was all about foreign policy. With wars still raging in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a Republican administration widely believed to have bungled both, Biden bet that his expertise as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was just what Democrats were looking for.

And so, at stop after stop — mostly in Iowa, where he was banking on a surprise fourth-place finish to propel him into later primaries — Biden touted his signature plan to split Iraq into three semiautonomous, entho-religious regions united under a big (if weak) central government: a loose Kurdistan, a loose Shiastan and a loose Sunnistan. “Are we going to be able to leave Iraq” and “leave behind something other than chaos?” he said in the first primary debate. “We have to change the fundamental premise of this engagement” by “decentraliz[ing] Iraq” and giving the regions “control over their own destiny.” He jabbed his rivals for not detailing their own Iraq policies, releasing an inaugural campaign video that declared him “the only candidate with a plan to get us out of Iraq and keep us out”; later ads highlighted all the times his primary opponents said “Joe is right” on foreign policy.

When President George W. Bush launched his surge in Iraq, Biden called soon-to-be Republican nominee John McCain “fundamentally wrong” for supporting it; he later described the surge as a “failed policy.” When the genocide in Darfur (a region in Sudan) led the news, Biden shifted focus, advocating for a no-fly zone over the region and a possible commitment of United States forces; when former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in late 2007, Biden seized on yet another overseas crisis, reminding voters that he had long described Pakistan as “the most dangerous nation on the planet” while strategizing about how to safeguard its nuclear stockpile.

Ultimately, though, Biden is making the same basic argument in 2019 that he made in 2007. His save-the-working-class theme is likely to have more resonance than his foreign policy focus. Yet his plan of attack is the same, tailored for a candidate who can’t compete with younger rivals for the mantle of change: Take the biggest problem we face, whether it’s national security (then) or blue-collar stagnation (now). What we need now isn’t newness. It’s expertise. The president is incompetent. My rivals are untested. Only I have the knowledge and gravitas to deliver.

“I’ll be as straight with you as I can: I think I’m the most qualified person in the country to be president,” Biden said during a book tour stop in Missoula, Mont., last December, according to CNN. “No one should run for the job unless they believe that they would be qualified doing the job. I've been doing this my whole adult life, and the issues that are the most consequential relating to the plight of the middle class and our foreign policy are things that I have — even my critics would acknowledge, I may not be right but I know a great deal about it.”

The problem with this message — perhaps the best one available to a candidate like Biden — is that it rarely works. In a lackluster field, it may be enough to eke out a nomination. (See Hubert Humphrey, Walter Mondale, John Kerry, and Hillary Clinton). But the last six non-incumbent Democrats to actually win the presidency — Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama — all emphasized generational change. Perhaps Biden can buck the trend, even if it didn’t work out so well for him last time. Or perhaps not.

Then there’s cash to consider. Biden has never been a prolific fundraiser, and 2008 was no exception. Over the course of 2007, Biden raked in a mere $8,245,241 — far less than Clinton’s $107 million, Obama’s $102 million, Edwards’s $35 million, former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson’s $22 million, or even former Connecticut Sen. Chris Dodd’s $10 million. In fact, Biden raised less money in all of 2007 than Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders raised in the first week of his 2020 campaign — and less than Sanders, Kamala Harris, or Beto O’Rourke raised in the first quarter of 2019.

All of which only underscores the uphill battle ahead. Biden’s Rolodex has certainly grown since 2008, due in large part to the eight years he spent crisscrossing the country as a top surrogate and fundraising draw for the Obama White House.

But the need attract financial buy-in not only from big donors and corporate interests but also small-dollar online contributors has grown as well. On that front, Biden has a lot of catching up to do. As the New York Times reported earlier this week, the former vice president is launching his campaign with zero dollars in the bank, and his “allies have pointed with concern to the $6 million sums that Mr. Sanders and former Representative Beto O’Rourke generated in their campaigns’ first 24 hours as the high bar against which he will be measured.” The hitch is that, unlike Sanders and O’Rourke — or even Kamala Harris, who raised $1.5 million in her first day — Biden does not have “an at-the-ready list of hundreds of thousands of contributors to ply for small donations,” and observers question whether he can muster the grassroots enthusiasm to build one.

In the meantime, he is relying on Democratic heavy-hitters to bankroll his bid. “The money’s important,” Biden reportedly told a group of top donors Wednesday. “We’re going to be judged by what we can do in the first 24 hours, the first week. People think Iowa and New Hampshire are the first test. It’s not. The first 24 hours. That’s the first test. Those [early states] are way down the road. We’ve got to get through this first.”

The final challenge Biden faced in 2008, meanwhile, was motivation. One of the major reasons Democrats didn’t rally around his presidential campaign at that time is because few believed that he was really, truly, deeply campaigning for president. Everyone seemed to think he was running for secretary of state instead.

“If, as expected, [Biden’s] underfunded and overlooked candidacy tanks in the early primary and caucus states next January, he’ll probably end up seeking — and winning — a seventh term in the United States Senate in the fall of 2008,” Steve Kornacki wrote in the New York Observer in June 2007. “But the job Mr. Biden may really be eyeing is that of Secretary of State. It’s a post for which the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, whose foreign-policy conversance was on full display in the most recent Presidential debate, is impeccably qualified.”

The skepticism about Biden’s intentions was so persistent — and his performance in the presidential sweepstakes so lackluster — that he was repeatedly forced to insist that he wasn’t pursuing a hidden agenda by remaining in the race.

“Absolutely, positively, unequivocally, Shermanesquely, no,” Biden said when Gannett’s Nicole Gaudiano asked in Iowa if he might be angling for the State Department, or even the vice presidency. “No. No. I would not be anybody’s secretary of state in any circumstance I could think of, and I absolutely can say with certainty I would not be anybody’s vice president. Period. End of story. Guaranteed. Will not do it.”

Biden, of course, accepted the veep nomination as soon as Obama offered it, so his motives will be examined in 2020 as well.

Today, the issue isn’t whether Biden’s target is the White House or some other post; he’s already served as senator and VP, so there’s nowhere left to go but up.

But there is some question, as there was in 2008, about whether Biden’s heart is really in this. Is he running because he “regret[s]” not running in 2016 “every day,” as he once put it, and needs to prove that he can succeed where Clinton failed? (“I never thought she was a great candidate,” Biden said in 2017. “I thought I was a great candidate.”) Is he running because he has always considered himself presidential material — he first mulled a run at age 37 — and just wants one more crack at his dream job before he retires? Or is he running because, as he put it in January, “I don’t see [another] candidate who can clearly do what has to be done to win?”

The evidence suggests that even Biden isn’t sure. For months, the former vice president dawdled about entering the race, missing a series of self-imposed deadlines while deliberating with his family in Nantucket and consulting with advisers in Delaware. Potential staffers defected; supporters worried that the delay was hurting his chances.

Yet even after the decision was made, Biden’s indecision didn’t end. A launch video filmed near his childhood home and crafted by his new media consultant, Mark Putnam, was “not favorably received by other advisers,” according to the New York Times, so the former vice president’s longtime aide Mike Donilon devised an alternative video, which was eventually released. Up until the eleventh hour, Biden’s campaign was debating where to rally first: in Charlottesville, Va., or in Delaware, or on the steps the Philadelphia Museum of Art made famous by “Rocky,” or even in Washington, D.C.

“I’ve never seen anything so half-assed,” a former Biden aide told Time’s Philip Elliott. “They’re improvising and doing last-minute planning. The guy has been running for President since 1987 and can’t figure the basics out, like where to stand on his first day? This should make everyone very nervous.”

Make no mistake: Biden can be an electrifying candidate, with a visceral sense of empathy and an uncommon ability to convey honesty and decency in both the largest arenas and smallest rooms. He is popular for a reason.

On the last day of 2007, three days before Iowa caucuses, I drove from an Obama event in Jefferson to a Biden event in Newton (as I reported in Newsweek at the time). The distance, in geographical terms, was about 100 miles, but it felt like light years. As always, the Obama event was clockwork: a hulking black press bus; volunteers asking for contact info at every corner; massive, well-designed banners; a stage filled with seated supporters.

The Biden event seemed smaller — even though it drew roughly the same number of people. The posters were droopy. Biden's family stood, arms crossed, on the periphery, whispering and smiling, and the candidate paced up and down the rows. No stage. No podium. No TV crews.

On the stump, Biden could get a little airy, especially when quoting his “favorite contemporary poet,” Seamus Heaney, on making “hope and history rhyme.” But he came alive, shifting from solemnity to bombast, when answering a question on, say, Pakistan. “I’m the only person running in either party, Democrat or Republican, who three months ago put out a plan for Pakistan,” he began, and 12 minutes later — after discussing the country’s religious demographics and reminiscing about that time Benazir Bhutto worked out of his Washington office, among many other things — he still hadn’t stopped.

At that point, Obama, Clinton and Edwards were well-oiled machines — delivery mechanisms for the “winning” messages their handlers had devised. But because Biden had no shot, he didn’t have to deliver a winning message. He wasn’t handled. He couldn’t afford handlers. Seeing him in person, the overwhelming impression you got was of a guy talking about what mattered to him, for better or worse.

That’s still the impression you get today. But despite his vastly increased prominence and astronomically improved polling, the same challenges that felled Biden in 2008 await him in 2020. And so he can no longer afford to be the candidate he was back then. To finally win, he must figure out how to be better.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump was ‘fighting for his political life,’ his former lawyer says

'It's already begun': Feedback loops will make climate change even worse, scientists say

Revealed: The U.S. military's 36 code-named operations in Africa

Video shows extensive fire damage inside Notre Dame Cathedral

Concerns mount over Jared Kushner's role in GOP money machine