Biden's COVID-19 relief bill includes an expansion of Obamacare. Here's how it would work

WASHINGTON – A 64-year-old woman whose $58,000 income puts her out of range for subsidized health insurance through the Affordable Care Act could see her premium drop from $12,900 to $4,950 under President Joe Biden's pandemic relief bill that passed the House on Saturday.

A 21-year-old man earning just above the poverty line could purchase a premium-free marketplace plan with a much lower deductible than he qualifies for now.

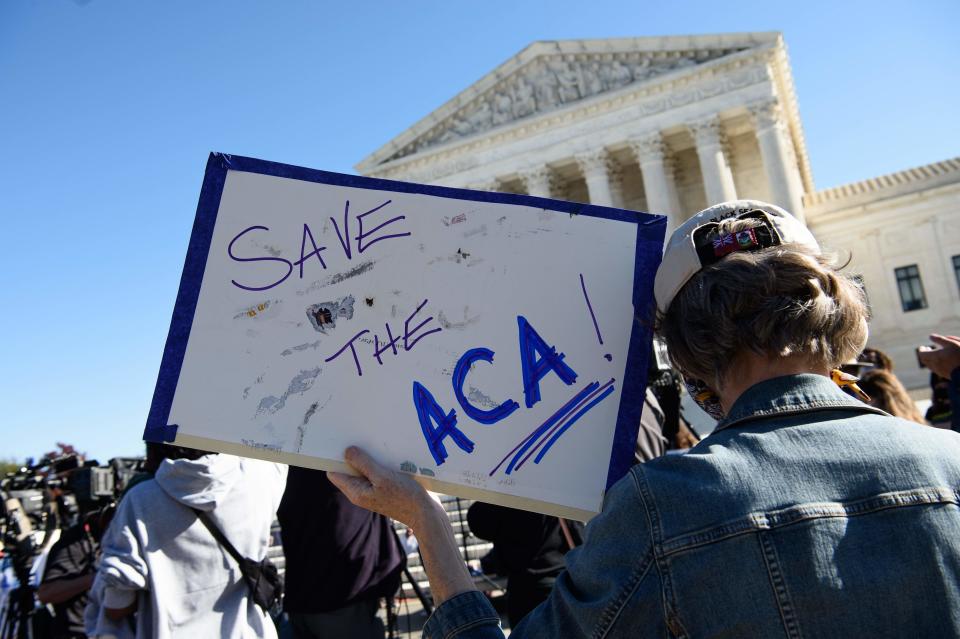

That potential boost in insurance help for millions of people would be the first significant expansion of the Affordable Care Act, also known as "Obamacare," since its passage in 2010. The Senate takes up the $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package this week, and Democrats hope it could be sent to Biden’s desk for his signature as early as next week.

In addition to the insurance subsidies, the pandemic aid bill would provide checks of $1,400 to millions of Americans, ramp up vaccine distribution and extend unemployment aid through the summer.

Though temporary, the more generous ACA provisions could lead to permanent – and even bigger – changes to the law that prompted a GOP-led government shutdown in 2013 and that President Donald Trump and Republicans failed to repeal when they controlled the White House and both chambers of Congress.

Republicans haven’t made the insurance subsidies a focus of their opposition to the bill they’ve dismissed as a “far-left wish list.”

Controversial when it passed, Obamacare has become more popular, and the pandemic increased the importance of access to health care.

Biden faces major challenges in building off this down payment to enact all of his proposed changes, including lowering the enrollment age for Medicare and creating a public insurance option. A public option was already a compromise from the more expansive “Medicare for All” system favored by liberals.

The billions of dollars the more generous premium subsidies would cost to enact permanently raises pressure on lawmakers to take much bigger steps than they've been able to do to lower how much providers charge for health care services by creating a public option or through other actions.

If private insurers paid hospitals and other providers at the same rate that Medicare does, health care spending for people with private insurance would be 41% lower than projected this year, according to an analysis released Monday by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan health research organization.

“In the U.S., we have done very little to address the underlying cost of health care, which is why health insurance is so expensive,” said Cynthia Cox, vice president of foundation.

Who would benefit

House Republicans call the expanded insurance subsidies “expensive and ineffective health coverage policies” that ignore the income of some enrollees to give them free coverage.

“While limiting these increases to two years masks the full cost of these expansions, lawmakers will feel tremendous political pressure to extend them, pushing the final cost still higher,” Doug Badger, a visiting fellow at the Heritage Foundation, wrote in an opinion piece for the Washington Times.

Under the COVID-19 relief bill, the insurance subsidies for people not covered through an employer or government plan such as Medicare or Medicaid would become more generous. They would be newly available to people earning more than four times the federal poverty rate. That's about $51,520 for a single person and $106,000 for a family of four.

The changes would provide the most savings to people at that income level who are older or live in areas with particularly high premiums.

A 60-year-old person making $55,000 per year living in Wyoming, West Virginia, South Dakota, Nebraska, Connecticut or Alabama could save more than 70% on a midrange plan, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The bill would guarantee that people with incomes up to 150% of poverty wouldn’t have to pay any premium for a benchmark midlevel plan, a step up from the higher-deductible plans they can buy with the current subsidies. That could mean the difference between having a $177 deductible instead of a $6,900 deductible plan.

“The increase in the generosity of the premium subsidies is quite significant and would make a very substantial difference both in terms of enrollment and in terms of lowering financial burdens on the population already enrolled,” said Linda Blumberg, an expert on health insurance at the Urban Institute. “I think of it as the first step in a broader agenda for improving the law.”

Democrats' efforts to hold down the overall cost of the ACA kept them from making the subsides as large as they wanted in 2010, leaving some lower- and middle-income earners to struggle to pay premiums and deductibles.

Two-thirds of the estimated $34.2 billion cost of temporarily expanding the subsidies would benefit people who have insurance. Additional subsidies to cover 85% of the premiums for workers who have been laid off or had their hours cut and premium assistance for people receiving unemployment insurance would bump taxpayers' bill up to more than $46 billion, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

Advocates and some analysts said that would buy much-needed help when many household budgets are strained. About 9 million people who are uninsured already qualify for a subsidy but aren’t taking one. Their top reason is cost, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“We’ve been talking about premiums and deductibles on the ACA markets being too high since it started,” Cox said.

Critics said that’s too big a price tag to cover the 1.9 million people that the CBO estimates would no longer be uninsured in 2022 if the bill becomes law.

Medicaid expansion incentives

The COVID-19 relief bill would increase pressure on the 12 states that have not moved to take the funding created by the ACA to expand Medicaid eligibility, leaving millions of people who are below the poverty line ineligible for government assistance.

“The Medicaid gap is the really greatest inequity in our current health insurance system, and it really needs to be addressed,” Blumberg said.

If those states increase eligibility, they would temporarily receive more federal funding than what it would cost to expand Medicaid. That may not be enough of an inducement “for conservative politicians reluctant to be seen as getting in bed with Obamacare,” said Greg Shaw, a political science professor at Illinois Wesleyan University who has written about the political debate over health care.

Some GOP-led states that rejected expansion didn’t do so largely for financial reasons, he said. “It’s because of the political optics,” Shaw said.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey “intends to keep an open mind” about what the new options might be, press secretary Gina Maiola told USA TODAY.

“Ensuring access to quality health care for all Alabamians has long been a priority for Governor Ivey,” Maiola said in an email. “Finding a way to pay for it has always been the challenge.”

In Tennessee, Gov. Bill Lee’s spokeswoman said the state is focused on revamping the traditional Medicaid program through a change in the financing system approved in January by Trump. The outgoing president gave the state more authority to run its program in exchange for capping the federal government’s annual share of the cost.

First actions: Biden signs executive action to reopen Obamacare enrollment amid COVID-19, end gag rule

Going beyond the relief bill

Health care was a top issue for Democrats in the past two elections, both as a potent political cudgel against Republicans as well as a defining force in the presidential primary.

Because so much of Democrats’ internal debate revolved around Medicare for All, which Biden opposes, it was “somewhat lost on people how sweeping his health proposal really was,” Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said on former Sen. Bill Frist’s health care podcast.

Efforts to make permanent the temporary provisions in the COVID-19 relief bill are underway.

Sens. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and Tim Kaine, D-Va., introduced legislation that they described as the closest match to the changes Biden promised as a candidate to build upon Obamacare.

Even though millions of people gained coverage through the Affordable Care Act, Bennet said, health care is the subject that most commonly drives people to tears at his town hall meetings.

The public option in their legislation would get momentum from expanding subsidies, Cox said, because it would increase the government’s need to hold down health care provider costs to keep premiums lower. A public option is a difficult lift because of pushback from the health care industry, and there are many technical issues to work out.

“We still have a long way to go before the U.S. has a good working model of a public option,” she said.

A public option has the advantage of being popular because people like the idea of having more choice, said Chris Jennings, a Democratic health strategist and veteran of political battles over health care. But it unifies health insurers and providers in opposition.

“It's got to be considered in the overall context of what you need in terms of savings and what you can pass,” Jennings said. “And I think that's still yet to be determined.”

More: Senate Democrats seek alternatives to $15 minimum wage in Joe Biden's COVID-19 relief bill

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID-19 relief package includes major expansion of Obamacare