The Biggest Problem On The Red Carpet Is Actually The Smallest

Bryce Dallas Howard revealed she bought her Jenny Packham gown off the rack from Neiman Marcus for the 2016 Golden Globe Awards, because she was a size 6, which was larger than the sample sizes offered by designers.

It’s red carpet season and many garments available to stylists for their celebrity clients are in the brand’s sample size, which is almost always a 0, 2 or 4. In most cases, there’s only one sample garment that has to be split between editorial (magazine shoots) and all the celebrity stylists who are requesting it.

“You’re splitting one sample amongst the entire world,” explained stylist Ariana Weisner.

And what if a celebrity isn’t actually a sample size?

In the case of Bryce Dallas Howard at the 2016 Golden Globes, she had to purchase her Jenny Packman gown from Neiman Marcus because, as a size 6, she couldn’t fit into the samples.

Weisner explained that, if this is the case, stylists have to break the news to their clients that their options are limited. While some designers do make “roomier samples,” she tells her clients that they have to be open to buying pieces if they’re a size 6, 8, 10 or above.

The fashion industry also has an annoying lack of any “standard” sizing across brands. While you may be a size 4 in one brand, you could be an 8 in another, which makes for all kinds of fitting room angst.

To understand why fashion works this way and how to deal with it, we talked to industry experts as well as some actors whose jobs require them to attempt to squeeze into these small sample sizes.

The Birth Of ‘Standard Sizing’

Before the Industrial Revolution, everyone from “peasant” to “royal” had clothes made and altered specifically for them, according to Keanan Duffty, an award-winning British fashion designer and educator. People without a lot of money would probably have two outfits: one that they worked in, and one they wore to church.

“But,” said Duffty, “their clothes were still made for them or, at the very least, fitted and altered in a bespoke [made for a specific person] way.”

With the Industrial Revolution came the invention of the sewing machine and the ability to mass-produce garments. That, in turn, birthed the idea (and necessity) of scaling products.

“In America, a lot of the standardized sizing information came from the military, which was the first group of people that garments were mass-produced for,” Gabby Brown, technical designer and apparel consultant, explained. This data set (obviously) only included measurements from this one group of people, not the entire population of the world (which, honestly, how would someone even go about collecting that?) Today, the ASTM, an international standards organization, tracks body measurements and occasionally conducts surveys of the same but, again, these only include small, (compared to the total population), specific groups of people.

“The system today is not that different from what emerged post-Industrial Revolution. And it actually doesn’t really work because every single person on the planet has a different body type and you can’t really standardize things,” Duffty said.

And therein lies the crux of the problem when trying to manufacture garments for as large of a section of the population as possible, or when a label creates what it considers its “sample size.”

How Brands Determine Their Sizing

Brands base their sizing parameters on their customer, which is why there is such a variation across labels. As Duffty explained, “It depends where in the market the brand is.” What he means by this is that a mass brand like Zara that probably has an early to mid-20s target audience will focus on sizing for that demographic while a designer label that does runway, like Gucci, will make samples that look good on tall, willowy models.

“Fit has always been a conundrum for brands: finding the correct fit for their consumer base is a big part of why brands succeed or fail,” Duffty said. Fit is also tied up in sourcing, or where the goods are made. (A size 2 in North America is different than a size 2 in Asia.) What you end up with is the “system” we have today, which basically translates into “every brand for themselves.”

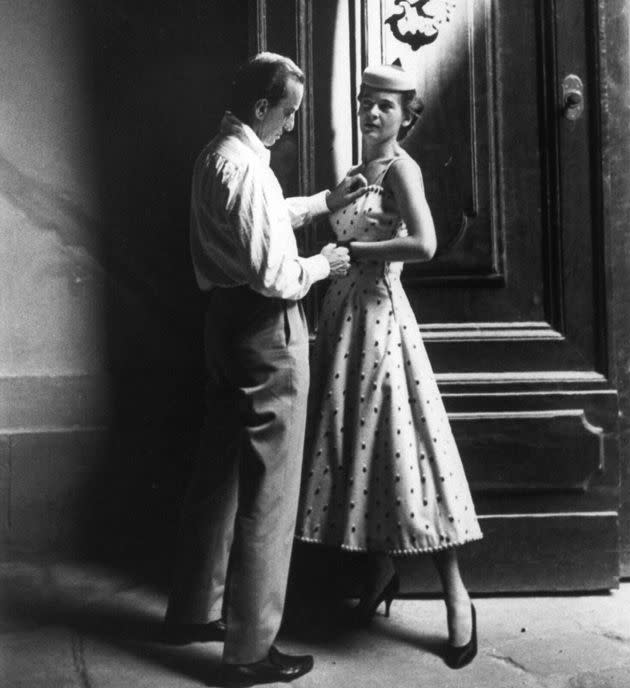

Italian fashion and fabric designer Emilio Pucci works with one of his fit models circa 1954.

Fit Models Help Determine A Brand’s Sample Sizes

Almost all companies use a fit model — someone who they feel embodies their target customer.

“Brands like Ralph Lauren use the same fit models for years,” Duffty explained. “Once they’ve got someone who is appropriate for their fit, they stay with them.”

Brown explained that a sample size in one brand is going to be totally different from a sample size in another. Always.

“They’re all different fabrics, different washes. They came from different factories, they have different fits. You can’t really compare apples to apples because it’s all apples to oranges,” she said.

Ideally, the fit model will fall into the middle of a brand’s size range. For instance, in a range from 00 to 18, the fit model will be an 8 or a 10, Brown told me. The size of a brand’s fit model, though, and their sample size may not be the same. The fashion industry, Brown explained, is filled with “people with very big personalities who want to see a certain look.”

And that “certain” look often means an idealized version of what size a body should be.

Brown explained that some company leaderships only want to see one body type in their meetings: a size 0 or 2. In this scenario, a brand might sample garments in a small size but they won’t use that sample size for their fit model. Instead, they’ll use a separate set of fitting garments that are the actual middle of their range.

“There’s a lot of phobia throughout the industry; people are afraid to see larger people in their showroom,” Brown said. This fear extends past the fashion world and well into the entertainment industry, where actors are often expected to look like the models who wear the sample size runway looks.

“I think, in the past, [actors] were expected to fit into sample sizes. Which is bananas to me and always has been,” actor Jaimie Alexander(of “Blindspot,” “Thor” and “Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.” fame) told HuffPost.

How Sizing Affects Actors Dressing For The Red Carpet

Everybody, including (and sometimes more so) actors, feel some pressure to look a certain way or have a certain body type. Even celebrities can experience inner angst and question their self-worth when in a fitting room.

“There’s a lot of pressure and a lot of fear. It’s tricky because [as an actor] you’re the product, right? For me, I’m curvy, but I’m still pretty small and I can be a size 2 in one dress but then a size 8 that needs alteration in another. And a size 8 sounds scary,” said actor Jo Armeniox.

“The fear is kind of like when you go to the hairdresser and they look at your hair and they say, ‘Oh God, who was doing your hair?’ When you have a fitting; they’re like, ‘Oh God, who was doing your body?’” Armeniox said, laughing. She went on to talk about how, while we (and she) may believe and understand that beauty doesn’t correlate to size, we aren’t told or reminded of that consistently.

And because of this, our inner dialogues often skew to the negative — which is rarely a good thing.

“Self-talk is big. External talk, internal talk, whatever you’re saying or thinking about yourself needs to be positive,” said Mia Holland, assistant professor of psychology at Bridgewater State University.

That’s easier said than done, of course. Most of us feel a certain amount of pressure from society, social media and advertising about how we “should” look.

“We know what it is, but it doesn’t make it necessarily easier,” Armenoix continued.

The Psychological Impact Of Sizing

What happens psychologically when you try on a garment in a size you think will fit and it doesn’t?

“First of all,” said Rachel Goldman, a licensed psychologist and clinical assistant professor at NYU School of Medicine, “emotions, thoughts and behaviors are all linked, which is the basic idea of cognitive behavioral therapy.”

Goldman explained that we have the ability to intervene at any point — at the thought, the emotion or the behavior. But this particular scene tends to go in a negative direction. When we try on something that we thought would fit and it doesn’t, we think things like, “I’ve gained so much weight,” or “I’m fat.” We arrive at the conclusion that something is wrong with us (even when we know that isn’t true). These kinds of thoughts, Goldman told me, are “automatic” thoughts or cognitive distortions.

“And sometimes they’re true and sometimes they’re not,” she continued. “All or nothing thinking is a common type of cognitive distortion, as are ‘should’ statements like, ‘I should fit into this size.’”

Research shows that we have 6,000 thoughts a day. What we need to remember is that they’re not all true. Goldman explained that our brains receive all kinds of external and internal messages throughout the day and it interprets those messages the best it can.

“Unfortunately, we live in this thin, obsessed cultural world so the automatic thought [interpretation] might be, ‘I should fit into this,’” Goldman said. For many of us, the thought that comes after that is usually something along the lines of, “There must be something wrong with my body.”

No one is born with body negativity, though. According to Holland, we learn this language as children. We focus on appearance in the most benign situations. For instance, she explained, if you run into somebody with their child, we commonly say, “Oh my gosh, you look so cute.”

“I think it’s incumbent upon adults to watch what we say to ourselves about ourselves and to others and to children and model better behaviors,” Holland said. Think about social media and all of these filters that everybody’s using — filters or things like bunny ears that people add to photos of their offspring.

“It appears benign, cute and funny, but we’re teaching children that unless you change the way you look, you’re not good enough,” she said. This type of language and thinking can lead to body image issues. “The most important factor in the development of eating disorders which are, by far, the deadliest of the psychological disorders,” Holland said.

Alexander, for one, strives to combat this. “I decided long ago that I would never doctor the images I put on my social media. It’s irresponsible. It’s incredibly damaging to others as well as myself. It’s important to remember that most of what you see in the media isn’t real, and isn’t actually achievable no matter how hard one might try,” Alexander said.

How To Better Navigate Body Issues And The Pressure To Be A Specific Size

First and foremost, Brown said, “Sizes in and of themselves don’t matter.” What she really wishes people knew and could do on their own is take their own measurements. That way they could look at size charts and know how to use those as a tool.

Knowing the arbitrary nature of sizes, though, often isn’t enough to quiet our inner, negative dialogues ― especially when we’re bombarded with images of people on social media with perfect skin, hair and clothes. As Goldman pointed out, social media is something many of us turn to when we’re bored or stressed. But, she continued, we should be mindful of who we follow, the media we consume and the messages we send to ourselves via that consumption.

The wonderful thing is that there are influencers and actors out there pushing back and speaking up about body image and the often unrealistic depictions of celebrities in social media. People like Alexander and Armeniox, for instance.

“I’ve always recognized the irresponsibility the media carries. As a society, for women, we tend to glamourize monetary wealth, flawless skin and being thin. Just know that most people have cellulite, skin blemishes, wobbly bits, scars, and other things they’re insecure about. So, when you see any type of ‘societal perfection’ in the media, it’s more than likely a lie,” Alexander said in an email.

And those stories we hear about a star who’s super voluptuous and got turned down by a designer because she wasn’t a size 8 or something? “Well, I know it’s real in the fashion world, but if that’s the case, then I just don’t want to wear their stuff,” Armenoix said.

As Goldman said, “The language that we use when we speak to ourselves and others is extremely powerful. And the words that we choose matter. When consuming social media, remind yourself that that isn’t real.”

“When I was much younger, there was an expectation that I should be a bit thinner than I already was,” Alexander said. “I no longer let others tell me what I should and shouldn’t look like. I’m too old for that shit.”

As are we all.