In blue-turned-red West Virginia, voters on both sides head to the polls with a sense of dread

HUNTINGTON, W. Va. – In a worn union office next to an Ohio River steel plant, Damion Elkins pointed to a framed photo of John F. Kennedy’s visit to the plant decades ago – a reminder that Democrats, powered by coal and steel unions, once held sway.

On Election Day today, Elkins and many of his fellow steelworkers plan to vote Republican, he said.

It's a vote cast not just out of allegiance. It's also, in part, out of fear.

Fear that more inflation will cost jobs. A stance in favor of new abortion restrictions. And a sense that President Biden’s 2020 election was "fishy.” Things won't change, he said, until Democrats no longer control Congress.

“We need to get the majority,” said Elkins, 50, who leads a steelworkers union.

In another neighborhood of this rust-belt city of 46,000, Pam and Ted Keesee have their own fears. Inflation and gas prices have meant tighter budgets and fewer meals out for the married couple, but that's not the biggest worry.

Instead, they're concerned about the disappearing access to abortion – West Virginia's near-total ban on the procedure took effect after this year's high-court ruling. And they worry about Republican election deniers subverting democracy, which Pam Keesee called “scary.”

“It feels like we’re going backward,” said Ted Keesee, a 51-year-old military veteran, shaking his head.

Across the country, voters head to the polls today to pick the candidates of their preference and the ballot measures of their choice. But many do so riddled with anxiety and a profound sense of dread.

Voters are worried about inflation, abortion, a raging culture war and clashing views over the future of U.S. democracy.

When voters in Huntington, West Virginia, talk about the election – Republicans and Democrats alike – they use words like "doomed" and frame the opposing party as going "off the deep end."

More: Poll monitoring raises specter of election violence, but experts focus on what happens afterward

More: Arizona becomes epicenter of concerns about voter intimidation

Democrats' fall from power

In West Virginia, there is no race this year that could shift the balance of power in Washington. There's hardly much question left about the state balance.

Just 14 years ago, Democrats held a legislative supermajority. Today, Republicans hold the governor’s seat and a state legislative supermajority. Twenty-one state legislative races fielded no Democratic challengers.

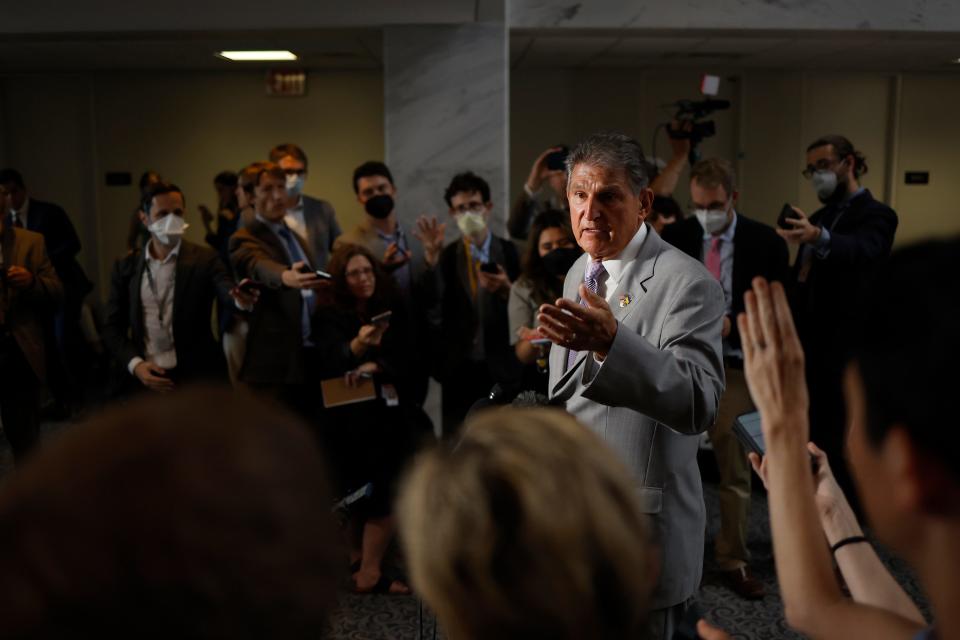

The state's congressional delegation is almost entirely Republican. Its one Democratic senator, Joe Manchin, is an outlier in his party – on Saturday he publicly slammed Biden for highlighting the push to retire coal-fired power plants.

Power had been shifting to the right as the strength of unions waned. Then national Democratic efforts to cut carbon emissions fueled support for Trump.

He won every single county in West Virginia in 2016 and 2020.

So a sense of dread may be particularly acute here for Democrats.

“It is easy for the Democrats to be discouraged,” said Marybeth Beller, a political science professor at Marshall University. The few remaining precincts that lean heavily Democratic are concentrated in a few larger cities, in the capital of Charleston, and around Marshall, in Huntington.

“West Virginia has a lot of very socially conservative people who have felt threatened as the nation has adopted more progressive policies,” Beller said.

She cited gay marriage as one such shift. West Virginia had passed a gay-marriage ban in 2000, but it was overturned in the courts, and the U.S. Supreme Court later affirmed a right to gay marriage nationwide.

Gay marriage isn't on the ballot, but another current political battleground is. Public schools nationwide have become the flashpoint of debates about race issues and pandemic policies.

West Virginians will vote on a constitutional amendment that would give the Republican-controlled legislature more control over the state Board of Education.

That’s just one change the state needs, according to Republican voter Connie Smith, 54.

Her pickup truck sports a window sticker of former President Donald Trump. In the back, there's a Trump-themed teddy bear in the back for her grandchild.

She said she's anti-abortion and afraid of Democratic policies and priorities. The current stance on immigration, gender identity and race issues, she believes, will take the country down a path from which it will be difficult to return.

“If we don’t take it back, then we really are doomed,” she said of Congressional control.

Huntington therapist Gene Surber, a Democrat who took advantage of early voting, said he is not optimistic of the chances of reversing Republican legislative control and repealing the abortion ban.

He felt the same way about challengers to incumbent Republican U.S. Reps. Alex Mooney and Carol Miller. Miller, whose district includes Huntington, voted on Jan. 6, 2021 to object to certifying elections in two states, calling into question the idea that Biden had won the election.

Surber said Democrats have been “too concerned about what pronouns you use” instead of focusing on economic issues. While the mid-terms are “incredibly crucial,” he said, “I don’t feel that hopeful, honestly.”

More: Is inflation swaying voters in battleground states? Here’s what we know

A vote on the economy

Few of the voters who spoke with USA TODAY saw positives in Democrats’ Inflation Reduction Act, which expanded Medicare benefits and increased home energy tax credits and rebates for Americans who purchase certain clean-energy appliances among other measures. No Republican lawmaker in the House or Senate voted for it – and many claimed it would only worsen inflation.

But most cited the need for more economic growth in Huntington, a city that has seen its share of economic struggles since the 1980s and has faced fallout from a state coal industry that has declined by 50% over the last decade, a West Virginia University study found last year.

In Huntington, that’s left 32% of residents living in poverty, creating an outsized impact from inflation that a Congressional report found cost households nearly $500 more per month compared to January of 2021.

Andy Fugeman, 62, sitting outside an apartment in Marcum Terrace, a subsidized apartment complex, said he hopes the election will bring more higher-paying jobs, help with child care and drug treatment in a state where overdose death rates have ranked among the nation’s highest.

Not far away, several students at a community college perched on an Appalachian hillside said they’d been turned off by the nation’s political divides and weren’t certain they would vote.

Brody Boykin, 19, who is studying multimedia design, said he hadn’t kept up with the issues. He and a friend said many young people believe their votes won’t make a difference.

Back at the steel mill, Elkins said the plant’s business had been helped by Trump’s tariffs – and hurt when they went away. At the same time, they have seen steel contracts for wind generators and solar farms increase.

But inflation and gas prices were still hammering workers, some of whom commute long distances to the plant. The jobs start at $19 an hour. Elkins blamed Biden’s pandemic spending for fueling inflation.

But like others in a state where many former Democrats were of a more conservative bent, Elkins’ political views aren’t monolithic. He thinks Democrats’ immigration policies allow for “an invasion,” but favors some state candidates who are Democrats because they support unions.

He said he’s turned off by both extreme ends of both parties and by what he sees as partisan media that has left him suspect of political news.

“Who do you believe? When you watch Fox News, they're saying one thing and you turn it over on MSNBC, and they're saying something totally different,” he said.

Elkins added: “We need a third party. We need a working-class party that falls somewhere in the middle.”

His fellow union steelworker Edward Clonch, 43, who has worked at the plant since 2006, also complained that politics had devolved into an “all-out war.” That has stained friendships and families, he said.

“We had two best friends who worked together. They went three months and never spoke a word to each other after Trump got elected,” he said.

Clonch said he views fears that Democrats will confiscate guns or that Republicans will subvert democracy as “scare tactics.” Whether the 2020 election was stolen? He’s not sure.

“You’ve got to hope it wasn’t, he said, that sense of dread appearing again, "or you can’t have any faith in anything that happens from here on out.”

More from USA TODAY

Abortion: Amid growing 'abortion deserts,' a haven in small-town Illinois takes shape

Climate change: Can Appalachia blunt the devastating impacts of more flooding?

Immigration: Inside the dire situation facing migrants bused across U.S.

Shootings: Texas DPS chief spent a career focused on protection. Now questions about Uvalde are looming

Chris Kenning is a national news writer. Reach him at [email protected] and on Twitter @chris_kenning.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Why once-blue West Virginia turned red, and what voters fear today