Born in the USA? Not so fast: Trump takes aim at birthright citizenship

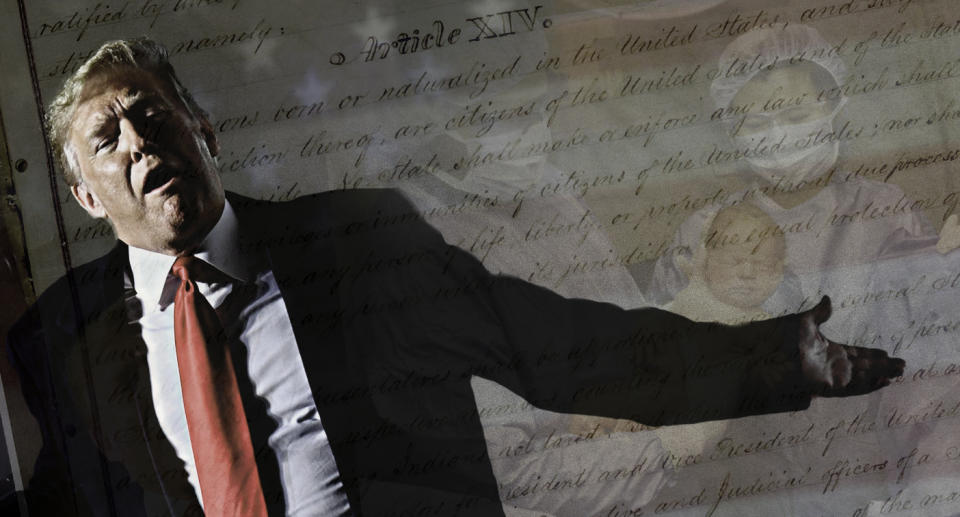

In an interview with “Axios on HBO” scheduled to air Sunday, President Trump said he believes he can end birthright citizenship with an executive order.

“It was always told to me that you needed a constitutional amendment. Guess what? You don’t,” Trump said. “No. 1, no. 1, you don’t need that. You can definitely do it with an act of Congress. But now they’re saying I can do it just with an executive order.”

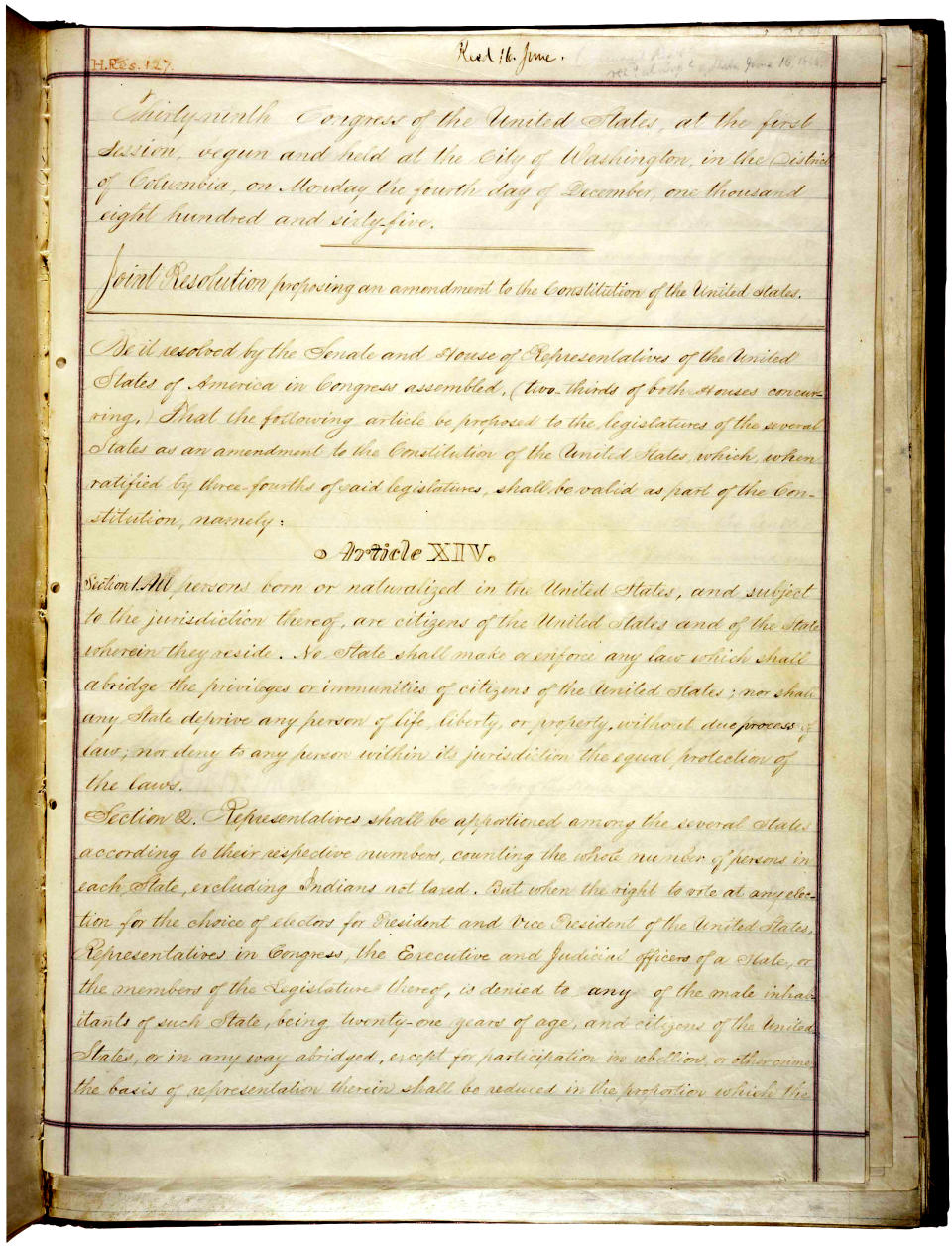

Trump called the concept of birthright citizenship “ridiculous,” even though it is guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States…” He claimed, falsely, “We’re the only country in the world where a person comes in and has a baby, and the baby is essentially a citizen of the United States for 85 years with all of those benefits.”

In fact, more than 30 countries grant citizenship to anyone born within their borders.

With just a week left before the midterm elections, Trump is trying to refocus the nation’s attention on what he sees as winning political issues — including immigration and border security. On Monday, the Pentagon said that on Trump’s orders it was deploying 5,200 troops to America’s southwest border ahead of the arrival of a slow-moving caravan of Central American refugees seeking asylum in the U.S.

Trump’s musings on ending birthright citizenship were viewed by many immigrant and civil rights advocates as part of his campaign to elect Republicans to congress.

“This is a transparent and blatantly unconstitutional attempt to sow division and fan the flames of anti-immigrant hatred in the days ahead of the midterms,” Omar Jadwat, director of the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, said in a statement Tuesday.

Jess Morales Rocketto, chair of Families Belong Together, described Trump’s proposal as “ethnic cleansing” and his plan to implement it by executive order “unconstitutional.”

“Americans will reject this cynical political ploy to stoke hate before the election,” she said.

Legal scholars overwhelmingly agree that Trump has no legal basis for what he intends.

“He can’t do that,” Laura K. Donohue, a senior scholar for the Georgetown Center for the Constitution, told the Wall Street Journal. “It’s basically saying the president is above the Constitution.”

Others scoffed at the idea that the law on the issue is unsettled or ambiguous.

“It’s not ‘unclear,'” University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck tweeted. “He can’t.”

In response to a tweet from NPR that said the constitutionality of Trump’s plan “isn’t settled,” Sarah Turberville, director of the Constitution Project at the Project on Government Oversight, tweeted: “C’mon @NPR… ‘not settled’? It was settled when the 14th Amendment was ratified. [Neither] The President – nor the Congress – can strip away citizenship from those born in the US. #POTUSisnotourking.”

Even House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wisc., said Trump does not have the authority he claims.

“You cannot end birthright citizenship with an executive order,” Ryan said in a radio interview on Tuesday afternoon.

“Obviously, Trump’s statement that he plans to somehow override the constitution by executive order doesn’t make sense,” said the ACLU’s Jadwat, “but it kind of falls into a long history of far right attempts to erase that constitutional guarantee or try to chip away at it.”

The case against birthright citizenship is one that’s long been promoted by anti-immigrant groups who, since the election of Trump, have seen views that were previously considered fringe and extreme embraced by the White House and congressional Republicans.

Among those groups is the Immigration Reform Law institute, or IRLI, the legal arm of FAIR (Federation for American Immigration Reform), a political nonprofit that seeks to reduce both legal and illegal immigration to the United States.

Jadwat pointed to an effort led by IRLI around 2010 to organize a coalition of state lawmakers to try to pass laws or resolutions that could form the basis of a legal challenge to birthright citizenship.

“That effort actually fizzled very quickly, I think both because it was such a fringe position politically … with so little public support and because I think anyone who took a look at it realized it ran into the same problem that the president’s plan runs into — the 14th amendment,” said Jadwat.

More recently, IRLI has continued to try to make its case against birthright citizenship in the courts. This summer, the group submitted an amicus brief in a lawsuit questioning whether people born in American Samoa should have birthright citizenship under the 14th Amendment. In their brief, IRLI stated that it, in fact, takes no position on that narrow question but opposes birthright citizenship in all cases, arguing that “Birthright Citizenship depends on birth in the United States to a United States resident who, at that time, both had permission to be in the United States and owed direct and immediate allegiance to the United States.”

Neil Weare, president and founder of the nonprofit Equally American and the lead attorney for the plaintiffs in the American Samoa case, said there are “certainly some troubling parallels” between the president’s latest proposal and the federal statutes his clients are currently challenging, which say people born in certain U.S. territories, such as Samoa, are not citizens of the United States.

“This discrimination against people born in territories came out of a very racist place,” he said, noting that it’s “not a coincidence that citizenship [was] being denied to residents of overseas territories who were overwhelmingly racial, ethnic minorities.”

“It’s troubling to see some of those same motivations at play today, with this push to deny citizenship to Americans born on U.S. soil simply because their parents have a different status,” Weare continued.

Weare emphasized that it is important to consider the timing and context of the 1868 enactment of the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” including former slaves, who’d previously been ineligible for citizenship under the Supreme Court decision, later nullified, in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford.

“It was enacted after the Civil War to overturn Dred Scott,” said Weare, explaining that the amendment was broadly and clearly written to ensure that citizenship “not be subject to political whims.”

“It’s a dangerous path to go down to be playing with something so fundamental as who are citizens of this country, who are ‘We the People,’” said Weare, warning that if an executive order eliminating birthright citizenship “were to be upheld in the courts, it would really be Dred Scott Part Two.”

In a statement on Tuesday, Dale Wilcox, the executive director and general counsel at IRLI, praised the president’s call for an end to birthright citizenship, arguing that the “Supreme Court precedent on birthright citizenship has been ignored or misstated for 120 years,” referring to the 1898 Supreme Court decision that upheld the constitutional guarantee of citizenship for anyone born on U.S. soil.

“The rule clearly excludes the children of both illegal aliens and tourists,” Wilcox’s statement continued, reciting a narrow interpretation of the 14th Amendment that has long been rejected by both liberal and conservative legal scholars. “The faulty interpretation of this rule has served as a magnet for large-scale illegal entry into the country and caused great harm to our sovereignty. The Trump administration is right to correct this error.”

Prior to Trump’s comments on Tuesday, some immigration law experts had pointed to the American Samoa citizenship case as a sign that birthright citizenship may be among the immigration issues considered by the Supreme Court in the coming year.

However, Weare and Jadwat dismissed concerns that Trump’s support for such a proposal might make ending birthright citizenship politically viable, citing long-standing bipartisan agreement on the meaning of the 14th Amendment.

“It’s a bedrock principle and one that has served the United States extremely well for over a century,” said Jadwat. “I don’t think there’s any real political support for trying to take citizenship away from people who are currently entitled to it.”

“Even the notion of doing that is just so repugnant and divisive that I think it would fail extremely quickly if put to a political test,” he added.

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham, however, suggested that he may be willing to put Trump’s proposal to such a test. On Twitter on Tuesday afternoon, Graham praised the president for his willingness to “take on this absurd policy of birthright citizenship,” promising to “introduce legislation along the same lines as the proposed executive order from President @realDonaldTrump.”

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ex-Obama official: U.S. ‘very vulnerable’ to power grid cyberattack from Russia

Leading for-profit prison and immigration detention medical company sued at least 1,395 times

Over nearly a century, Rose Mallinger saw the best and worst of America. Until Saturday.

Photos: Mourning the victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue attack