Can Ben Jealous win in Maryland and point the way forward for Democrats?

BALTIMORE — On a cloudy summer evening in the Park Heights neighborhood in West Baltimore, about 100 people mill about an elementary school yard. They are drawn by free food, raffles and the presence of community groups who have set up shop as part of National Night Out, a nationwide series of events designed to promote public safety and violence prevention.

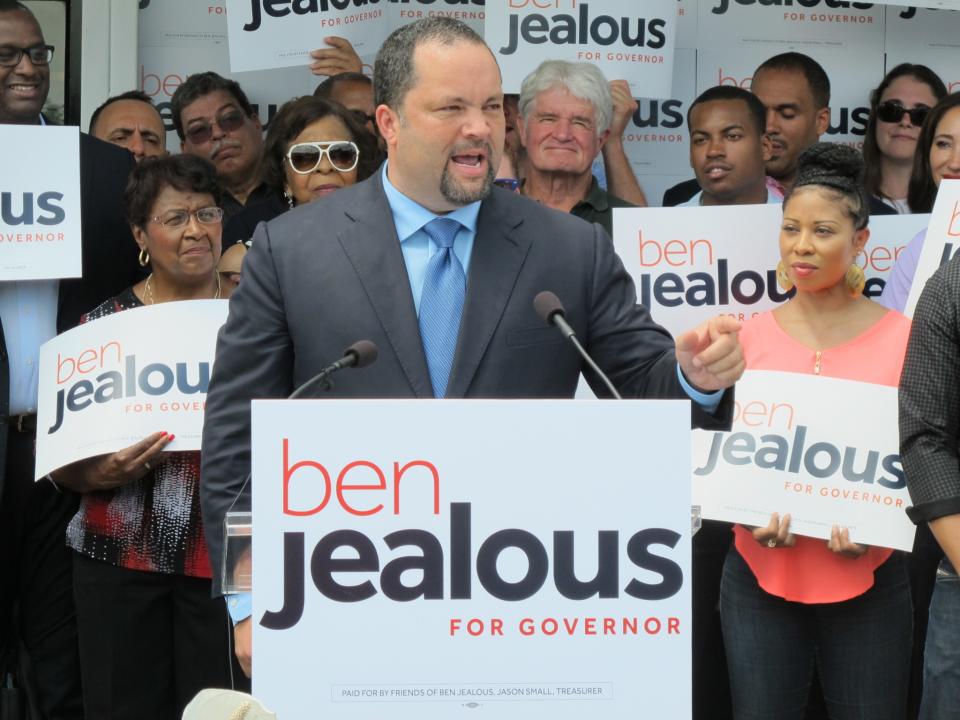

They are not there for politics, but Ben Jealous is here anyway.

The former NAACP president turned Maryland gubernatorial candidate makes his way through the crowd, shaking hands in a city that his family has lived in for more than 80 years. His presence brings a jolt of energy to a rainy evening and his banter with residents feels less like that of a politician schmoozing voters than of old friends reuniting.

“I know what it takes for a family to go, in a generation, from raising a child in the projects in West Baltimore, to saying goodbye to a child going off to Oxford University [on a Rhodes Scholarship],” he said. “You have to create a context where hard work is enough.”

In the car to the next National Night Out event located a few miles away, Jealous describes visiting family in the area growing up, when the houses had a fresher coat of paint and their original marble steps were still in place. Those days have long since passed, and West Baltimore has only nudged its way into the national consciousness through reruns of The Wire or when an article appears on the anniversary of protests sparked by Freddie Gray’s 2015 death in police custody, which occurred in the Gilmor Homes housing project just blocks away from Park Heights.

Residents say they appreciate Jealous’ visit to their community, which tends to be ignored by the state’s political machine.

“On a very basic level, it shows a level of interest and affirming … that Baltimore is an important part of the state overall,” said Monica Watkins, president of the Baltimore alumnae chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority, which helped organize the event in Park Heights.

But the race he entered has the potential to turn messy. A half dozen Democrats have already thrown their hats in the ring, and other prominent state figures are weighing a run, enticed by a political climate favorable to Democrats, especially in true-blue Maryland.

But there’s also the matter of incumbent Republican Gov. Larry Hogan, who enjoys a 65 percent approval rating, according to a March Washington Post-University of Maryland poll. This despite the fact that Hogan was elected in a state where Republicans are outnumbered two to one and Democrats control the state Legislature with a supermajority.

Hogan has preserved his popularity in the Old Line State by focusing on job creation and steering clear of President Trump, who he declined to endorse last year. He also avoids litigating social issues, such as abortion, something that made his 2014 campaign different from those of previous Republicans in the state.

Jealous’ campaign is undaunted by Hogan’s approval ratings, noting that voters respond less favorably to the idea of reelecting the Republican, and polls show a generic Democrat within striking distance of the 61-year-old incumbent. But there is little doubt among observers that Hogan is a formidable opponent, even in a year in which other Republicans may struggle.

The message Jealous is taking to voters, including those in West Baltimore, is unabashedly progressive. That’s not exactly a shock, considering he was the co-chair of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign in Maryland.

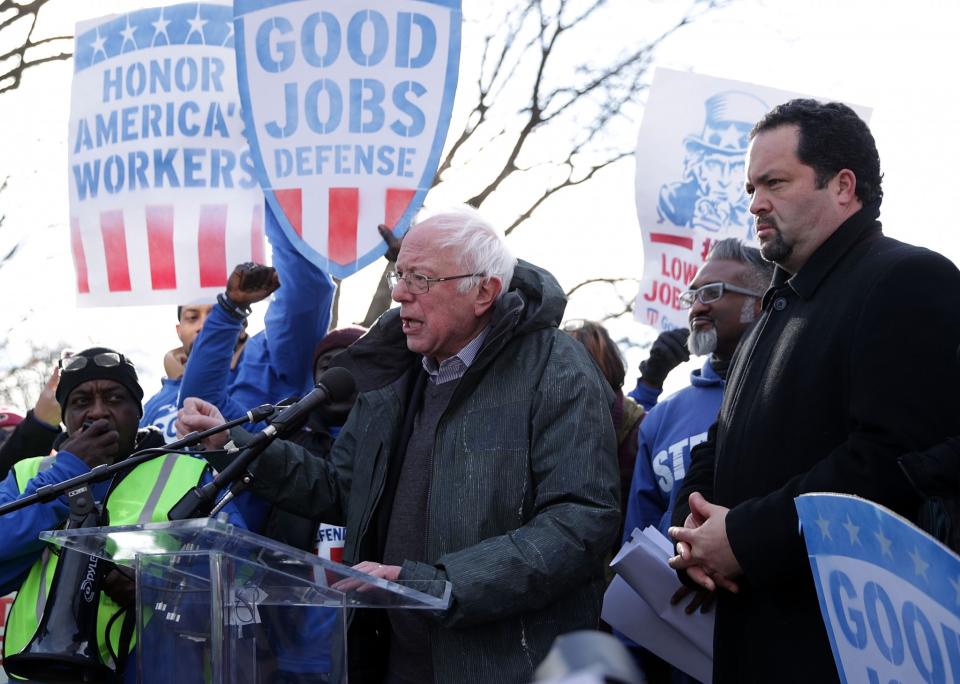

Sanders himself even endorsed Jealous in July, making him only the second candidate that the Vermont senator and his Our Revolution organization have backed in a 2018 race.

“[Jealous is] one of the great progressive leaders, not only in the state of Maryland, but in the United States of America,” Sanders said at a rally in Silver Spring last month.

Aides for Jealous’ campaign say this endorsement is major boost, pointing to internal data showing that Sanders is the most popular political figure in the state, especially among African American voters, who give the Vermont senator an approval rating of 82 percent.

Jealous stresses that his campaign is unique but also doesn’t deny his ties to Sanders and the progressive movement.

“I’m running as Ben Jealous … I’m blessed to have been both president of the NAACP and co-chair of Bernie Sanders’ campaign in the state,” he said. “And that gives us a strong foundation for building a multiracial coalition of working families.”

Jealous’ record of activism is undeniably impressive. While he has never held elected office, he is the youngest president of the NAACP and his leadership turned that organization from one struggling to maintain relevance into a political force. When he stepped down in 2013, Jealous’ leadership had helped turn the Baltimore-based group into a financially solvent and modern organization, buoyed by the victory of President Barack Obama and a number of state and national victories.

In Maryland, Jealous was successful in mobilizing members in efforts to ban the death penalty, legalize same-sex marriage and approve a state version of the DREAM Act. All of those measures passed the state legislature.

Jealous got his start organizing as a student at Columbia University. Suspended for a semester for his role in a protest against the destruction of the historic Audubon Ballroom, the site where Malcolm X was assassinated, Jealous also spent time as a community organizer in neighboring Harlem and interned for the NAACP’s legal defense fund, a precursor of things to come.

All of these factors, Jealous and his supporters argue, put him in a favorable position compared with past progressive candidates. But others in the state are skeptical that an unabashedly liberal message will help Maryland Democrats take back the governor’s mansion.

Todd Eberly, an associate professor of political science at St. Mary’s College, said that Hogan’s win in 2014 was a product of his appeal to moderate Democrats and independent voters. He argues that moving to scoop up those centrists, not shifting to the left, should be the strategy of both state and national Democrats.

“If they run against Hogan with a dyed-in-the-wool, Bernie Sanders-style progressive Democrat, then I think they make Hogan’s reelection almost inevitable,” Eberly said. “So they have a problem. The candidate who is going to win in the primary is probably exactly what they don’t need in the general election.”

Jealous’ progressive message may indeed win him the primary, Eberly notes, and a similar platform could well lift other leftist candidates nationwide. But raising the minimum wage and securing free public higher education and single payer health care, all tenets of Jealous’ platform, may struggle to attract more moderate voters, Eberly added.

“I think [Jealous] has a hard time with a broader appeal, he has a hard time bringing independents and moderate and conservative Dems back in the fold,” he said.

But Jealous disagrees, arguing that the party will rally around a liberal candidate in a way they would not with a more moderate politician.

“There are other folks in the party who believe you beat Republicans by being Republican-lite. Republican-lite doesn’t inspire anybody, it doesn’t inspire Republicans, it doesn’t inspire Democrats,” Jealous said. “This notion that the pathway to victory is mediocrity is laughable, and we are at our best when … we are on fire about defending Americans’ basic freedoms and dignity and ending poverty and expanding opportunity. And that’s what this campaign will be about.”

Jealous and those like him argue that progressive Democrats, especially in states like Maryland, where the party has slipped in recent years, are necessary to regaining prominence.

“You can never out-Republican a Republican, right?” he continued. “But you can beat a Republican as a Democrat in a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans two to one.”

Nina Turner, an Ohio state senator and president of Our Revolution, agrees with Jealous’ assessment.

“We’re asking people at a very critical time in our nation’s history to just settle,” Turner said. “Why should we dream a better dream, why should we try make things better for ourselves and future generations, let’s just settle. Why reach high? And I just don’t believe that, in this atmosphere that people should just settle.”

But the win-loss record for candidates supported by Sanders and Our Revolution has not, to say the least, been sterling. Although progressives have notched some key victories in local races, those running for statewide and federal offices have had less success.

Tom Perriello, a former congressman and progressive supported by Our Revolution, lost the race to replace Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe to the more moderate lieutenant governor, Ralph Northam.

In Montana, Rob Quist, who campaigned on multiple occasions with Sanders, likewise lost his bid to fill the congressional seat vacated by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke by five points. This was despite his opponent, Greg Gianforte, infamously assaulting a reporter in the waning days of the race.

This lack of success has given rise to debate within the Democratic Party not dissimilar from the one playing out in Maryland. Those on the left say that the path to victory in 2018 and beyond is to embrace the progressive wing. Others within the party say that a more moderate approach is the key to winning back Republican seats and voters who have slipped through their fingers in recent elections.

“It has to be … bold,” Turner said of the message Democrats need to take to their constituents. “Not just half measure kind of stuff and tailoring the message based off what kind of district you’re running in. There are some things that are just basically fundamental and these things are not radical ideas.”

No matter the race, the messaging issue boils down to the same central question: How does the Democratic Party regain voters it has lost? While past Maryland elections may have been decided by voters along the I-90 corridor in the Baltimore-Washington area, Eberly said that the goal for state Democrats should be to find a candidate who can appeal to voters in the more conservative Baltimore suburbs, as well as cutting into Republican support in rural areas.

“It’s a party that, at the moment doesn’t have broad geographical appeal. And running more to the left, reinventing more to the left, isn’t going to be what gets them that broad appeal,” Eberly said.

Jealous’ message to voters, however, is plain and simple: He is that candidate who can get that broad appeal and unite Marylanders of all stripes behind his progressive message. And his stature within the African-American community, a demographic which Sanders’ candidacy struggled to win over, could serve as a playbook for future candidates of color who embrace a progressive platform.

As Turner notes, the traditional Democratic playbook has not found success in recent election cycles either.

“It boggles my mind … the whole criticism of the progressive movement in terms of the win column,” Turner said. “When over the last 10 years … they’ve lost 1,100 seats over all levels of government, particularly the state level that Democrats turned their backs on.”

Jealous said that if Democrats stick to their party’s roots they can find success in Maryland and beyond. Part of that is moving beyond what he called the “temporary divisions” of the last election.

“This is not about the state of our party in 2016, it’s about the state of our children in 2036,” he said. “And from Bernie [Sanders] to [Cory] Booker, we are seeing our party’s leadership realize that we have an opportunity here to show the country that when Democrats run as Democrats we win and we win big.”

Read more from Yahoo News: