Can rescue animals change the way we grieve?

Psychologist and grief counselor Joanne Cacciatore is walking across the sprawling land of her Selah House Respite Center and Care Farm, on the outskirts of Sedona, Ariz., toward the high metal fence of the horse pen. There’s a fall heat wave, and her deeply tanned arms — tattooed with an artful array of black-ink images that range from St. Francis of Assisi communing with birds to the Psalms quote “God is nearest the brokenhearted” — glow in the blazing sun.

Four mellow horses stand grazing in various shady corners, but we’re headed for one in particular: Chemakoh, who is a beautiful reddish-brown with patches of white.

“He’s my soulmate,” says Cacciatore, and calls out his name as we get closer. He’s waiting for her at the gate, and she leans right into his broad face, cooing, “How are you? How’s my baby?” He shudders and flicks his tail and looks back at her intently through fist-size eyes.

The horse is healthy and beautiful — a far cry from when Cacciatore just happened to come upon him two years ago, hiking with friends on a trail along the Grand Canyon’s south rim. Then, he was starving and abused and bleeding, packing 150 pounds of gear for a hiking group, and he had fallen down out of exhaustion. When his handler began to yell at him and hit him, the deeply empathetic Cacciatore stopped in her tracks and sat down in the dusty dirt with him, crying.

That split-second decision brought an abrupt end to her backpacking journey deep into the remote Havasu Canyon, a trip she’d been planning for decades. But suddenly she had a new goal — to rescue the horse — and three determined days and nearly 100 calls and emails later, Cacciatore made it happen.

“I had to fight for him,” she says now, feeding him carrots out of her open palm. “I made a lot of noise. I took a lot of pictures and videos of the abuse. And when I was not allowed to take him on sight I said to him when I was leaving, ‘You’ve got to remember me, because I’m going to come back for you.’ I promised I was going to get him out.”

Volunteers soon delivered him to Cacciatore’s house in Sedona. “There were about eight people there that day, but he got off the trailer and whinnied and walked right over to me,” she recalls. “It’s like he was saying, ‘Hey, you came back for me.’”

She named him Chemakoh, a Pima (Native American) term that refers to two souls that come together in destiny, and though she’d had zero experience with horses before his arrival, she began to love and nourish him back to health. And so did her clients, bereaved parents who would come to see Cacciatore for intense private sessions, and soon find themselves drawn to the rescued horse in her backyard.

“They would go out to his paddock, and they would stand at his fence and just cry. Bring him carrots and just cry. And I could see this connection,” Cacciatore’s says. “People said, ‘Look what he looks like now. Look at what love can do, look what compassion can do — and they started seeing themselves in this horse. And I’m like, ‘Oh, there’s something really important happening here.’”

Seeing those connections, fostered between grieving humans and the badly abused horse, was ultimately what led Cacciatore to the idea of opening Selah, on land embraced by canyons and pine thickets and the iconic red rock mountains. Just five months in and not yet fully up and running, the care farm is already home to a fast-growing menagerie of rescued horses, sheep, dogs, and (so far just one) pig. And it is a unicorn of a place, where people can come and find solace after suffering the death of a loved one, often through bonding with an animal, such as Chemakoh, who truly seems to understand.

Because while the idea of care farming in general is rare enough outside of Europe and Australia —where the “green” approach to therapy utilizes the natural healing power of land and animals to help people deal with issues from spectrum disorders to PTSD and addictions — Selah is rarer still. That’s due to it being the first care farm ever to focus on treating the traumatically bereaved.

“This farm is a place where people can go in their trauma and grief and get some space, and just be with their authentic emotions,” Cacciatore says, adding that the name comes from the Hebrew selah, meaning an interlude during which to pause and reflect. “There aren’t very many places like that in the world, where you can have that space and freedom to just be.”

Selah is still in its infancy, actively fundraising so that the actual brick-and-mortar therapy residence center, for weeklong stays, can be built. But it’s already bringing deep comfort to pretty much anyone who spends any time here, either for daytime visits or to volunteer on the land — people like Roger and Jennifer Huberty, whose daughter Raine was stillborn in 2011; Beth DuPree, a breast cancer surgeon whose brother was killed by a drunk driver when she was in high school; Diane Keller, whose 18-year-old daughter was murdered at college in 2010; Rachel Tso, whose 3-year-old son Zaadii was run down in 2015 by a distracted driver in a Best Buy parking lot; and even this writer, grateful to find a place at which to plumb the depths of grief, no matter how old or frozen over, decades after surviving the drunk driving accident that killed her brother and best friend.

Selah’s comforts are simple but immense, gained by caring acts like brushing a pig, feeding a baby sheep its bottle, putting one’s hands into the warm earth to plant flowers, or just sitting and crying under an almond tree.

“Animals just have this innate ability to connect with us humans in a completely nonjudgmental way,” says Joel Bacon of Connecticut. He and his wife, JoAnn, lost their 6-year-old daughter, Charlotte, in the Sandy Hook school shooting five years ago this week, and have made many trips to Sedona for both counseling sessions and retreats with Cacciatore. When their son Guy, now 15, returned to classes after his sister’s murder, it was the presence of therapy dogs brought in by the school that made it bearable; the family has since created a program called Charlotte’s Litter, which advocates for the use of therapy and comfort dogs. “They help us to feel,” Joel says of animals, “which is so important, especially when it comes to grief.”

It’s this cycle of compassion — from human to animal and earth and back again — that Cacciatore hopes will be the heartbeat here.

“I believe that the people who have suffered are the peacemakers in this world,” she says. “If we can stay with our pain and stay with our grief, we can know a compassion that is boundless, and we can enact that in the world. It doesn’t make it OK that that person we loved most in the world died, and it shouldn’t. And yet we still can bring that love to the world in an amazing way.”

Or as Tso, who owns horses, says, “I sometimes find myself more able to relate to animals than people. We’re all these sentient, living beings, and to be able to look into the eyes of an animal who has been through trauma and is learning how to live day by day, just like me? It’s powerful.”

“Being a warrior is learning how to cry.” — Nathan Chasing Horse

The practice of care farming has gained a toehold in countries including the Netherlands, Australia, and the U.K., where there are currently 250 care farms operating and another 100 in formation, according to a recent report from the nonprofit Care Farming UK. In the U.S., besides Selah, there are only three known setups — two in Oregon, Fawn Hills and Sanctuary One, and another in California called Kindred Spirits — mostly serving the youth and the elderly through informal volunteer offerings that involve rescue animals.

And there are similar types of “green,” outdoor-based therapy programs, including Operation: Tohidu in Maryland. In the program, clinical psychologist Mary Vieten treats veterans with PTSD through outdoor group retreats involving ropes courses, ziplines, yoga, and equine therapy, which “helps them manage their own healing naturally,” notes the website.

Still, Cacciatore’s vision for the care farm and her approach to grief in general is exceedingly rare. That’s even as public discussion of the oft-avoided topic of grief has begun to blossom, the result of both a steady clip of mass-scale American tragedies and the willingness of those with major platforms — Joe Biden, Sheryl Sandberg, Prince Harry, Jennifer Hudson, and Joan Didion among them — to speak and write with heartbreaking honesty on what it feels like to be bereaved.

But the role of animals in helping to soothe grief was something Cacciatore has had a sense of for many years: In 1994, she gave birth to her fourth child, a girl named Cheyenne, who was stillborn. It was a life-altering moment that catapulted her into her current role of renowned expert on the topic of traumatic grief, defined as the emotional reaction to a loss that is sudden, unexpected, or violent, or any death of a child. Now she counsels the bereaved and trains other therapists to do the same, runs her national MISS Foundation (a support organization for parents who have lost children), and researches grief in her role as a PhD and tenured professor of social work at Arizona State University.

Earlier this year, she released her fourth book, Bearing the Unbearable: Love, Loss, and the Heartbreaking Path of Grief, to much acclaim. And despite spending an inordinate amount of time talking, thinking, and hearing about death, Cacciatore exudes a deep, glowing joy and a fierce, unwavering presence.

But, she says, for a while, after Cheyenne died, she remained in shock and immobile. She wept frequently.

“I had dogs at the time, and I used to say my dogs and my 3-year-old were the only beings that could stand to be around me without trying to change how I felt — without trying to cheer me up or make me better,” she recalls. “They just accepted when I cried and just accepted my grief… when none of the adults around me could.”

When Cacciatore began to notice that same quiet intuition between her horse and her clients, she researched equine therapy programs, and discovered that while the approach was used for combat veterans and children with disabilities, there were no examples of it being applied to bereavement.

Eventually, she came upon the writings of Rich Gorman, an England-based postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Exeter with expertise in care farming.

Gorman had been looking at how care farming could be more compassionate, as the “therapy” animals in most such settings are part of the existing agricultural system and are eventually sent off to slaughter. So he was intrigued when Cacciatore, a longtime vegan and a Zen Buddhist priest, reached out to him with her vision, which included the compassionate twist that every animal be a rescue.

“It’s an area no one has really looked at before, so I was fascinated,” Gorman says, referring to the pairing of care farming and grief. “The most exciting thing for me was her story about Chemakoh, and this use of bringing human and animal care together.”

Gorman headed to Sedona, where the two set to work creating a blueprint for this rare respite center and writing a meticulous review on their vision, publishing it in the journal Health & Place.

Components of the farm, once it is up and running in early 2018, are to include group and individual counseling with Cacciatore and a small staff of therapists, animal-based therapies, contemplative practices such as yoga and meditation, and space for other activities, such as kayaking along a narrow offshoot of the Verde River, which snakes along the 10-acre property. The aim is to have costs for a stay here be on a sliding scale based on ability, with no one turned away for lack of funds.

For now, nature is the center of the action. Small boulders artfully edge the crimson-dirt paths, and the land is alive with grapevines, weeping willows, and pomegranate trees. Benches dot the property, along with signs that Cacciatore has had made up, bearing quotes about grief from Wendell Berry, Margaret Brownley, and the Book of Psalms. There is a swimming pond near the entrance, a raised yoga platform, and a metal “memorial tree,” onto which mourners can affix round copper tags bearing the metal-stamped names of those they’ve loved and lost. (I take part in the ritual, hammering “Adam” and “Kristin” into shiny discs, letter by tiny letter, and the effect is startlingly, physically profound.)

Chemakoh remains the original mascot, but he’s since been joined by a steadily growing army of beings, from abandoned dogs and formerly slaughter-bound sheep to other abused horses and a sensitive pig named Wilbur, who was left alone in an empty house for one month before he was found, and now has an insatiable appetite for oatmeal with brown sugar.

The actual “house” of the Selah House, which will have room enough to shelter several families at a time, has yet to be constructed, as land was only just purchased in August by Cacciatore and her engineer husband, a “superduper private dude” who prefers to remain in the background. (For now, visitors either live in the area or stay at a small guesthouse adjacent to Cacciatore’s own, just a few miles away.)

Fundraising toward a goal of $585,000 has been a painstaking process.

“I think people don’t want to fundraise to be part of a grief process,” posits Nancy Borreani, a Massachusetts mom who lost two children within five years — a son, 25, in a 2010 drunk driving accident, and a daughter, 23, to cancer in 2015 — and credits Cacciatore, and the care farm, with saving her life. “People want to talk about happy things, or they want to fundraise for something to have a cure, like cancer or MS,” she says. “There isn’t a cure for this.”

Still, contractors have built a barn for Chemakoh and his cohorts, and there is a steady sound here of hammering and digging, as groups of volunteers come together to take on tasks from irrigating the land to hacking down overgrown bamboo thickets and planting flowers around what already feels like a magical corner of the world.

“You cannot rush your way through grief.” — Margaret Brownley

An essential part of Selah is the community of support and understanding among fellow mourners that the programs aim to build. It’s something those who are grieving say they cherish when found, though it’s often difficult to find in a society that desperately wants them to keep busy and move on — and when they don’t, that often moves on instead.

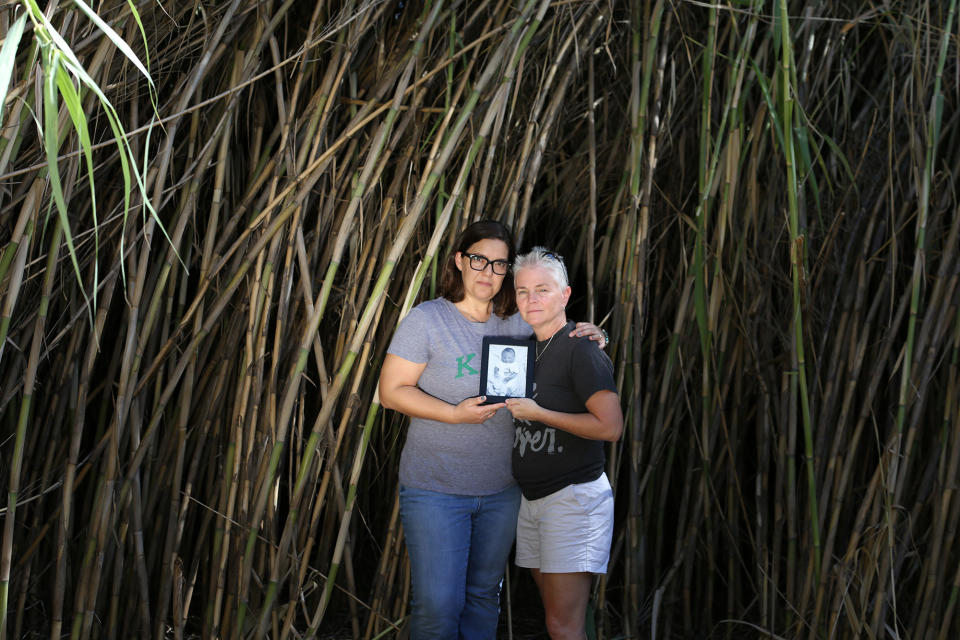

“We lost a lot of friends,” recalls Rae-Ann Wood. She and her wife, Sarah Toig, began working with Cacciatore after their son, Noah, was stillborn in 2010. “They couldn’t handle the grief, they couldn’t handle our pain, they didn’t know how to respond. I think they wanted us to be better, to get over it.”

Billie Freiwald, whose 3-year-old son Braden died from complications after a routine tonsillectomy in 2008, reports that after some initial offerings of comfort, people kept their distance. “My best friend who was there when he was born disappeared,” she tells me, sitting with her husband, Jason, in the fading orange glow of a sunset one evening at the care farm. “I think people are scared. I mean, you go to the grocery store… and people would see you, and you see them out of the corner of your eye, and they run — I mean run — the opposite way.”

Similarly, says a weepy Maya Thompson, whose son Ronan died of the childhood cancer neuroblastoma just before his 4th birthday in 2010, “I walk into my daughter’s preschool, and I’m like every parent’s worst nightmare.” She’s visits Selah regularly, and talks with me here while sitting on a bench beneath a mulberry tree trimmed with a rainbow peace flag and various wind chimes made by bereaved parents. “I think it’s too much reality [for others], because this could happen to anybody — anybody can lose a child, and a lot of people don’t want that reminder.”

Thompson, who now helms the Ronan Thompson Foundation, is writing a memoir of her loss, and has a large and loyal social media following, spent time during Ronan’s treatment meting out heartbreaking updates through her blog, Rockstar Ronan. It went viral after attracting the attention of Taylor Swift, and the pop star eventually wrote a song about the blue-eyed boy using one of Thompson’s posts as lyrics.

But in the early days of her son’s treatment, a well-meaning friend suggested to Thompson, who was sobbing, that she get herself on antidepressant medication — not a rare suggestion for the bereaved — which she did.

“I didn’t know what I was doing,” she recalls, as Wilbur the pig rubs up against her ankle as if he were a cat. “I thought it would help, so I saw someone and they put me on a cocktail of so many different things, and I went through Ronan’s treatment very numb.” But instead of providing comfort, she now knows, the drugs simply pushed away the inevitable.

“Once I was off those medications, I feel like I was able to start the healing process a bit,” says Thompson. “I know I was suicidal when I was on them. I didn’t ever want to be numb to my pain.” Though her grief shifted in a life-altering way after she started working with Cacciatore, she says, “There’s never a second that I’m not carrying the grief with me. It never goes away.”

The idea of fighting grief by pushing it away or deadening it with psychotropic medications or other substances is a distinctly Western one, Cacciatore says. And she ardently believes it needs to change.

“There’s so much we [in society] get wrong about grief,” she says. “I think all this striving for feeling good is really doing us quite a lot of harm. The fact is that life is hard sometimes, and that means we have to feel painful feelings and learn how to bear the unbearable. All of this happiness-chasing doesn’t do us any good, because what we wind up feeling is, if we’re not happy all the time then we’re not doing something right.”

Furthering that dilemma, notes Cacciatore, is a systemic problem among caregivers, because “we’re no longer teaching therapists or psychiatrists how to be with people who are suffering,” she says. “We want to fix people rather than just be with them.”

A striking example of this was the controversy that erupted among mental-health professionals when the latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) came out in 2013. Published by the American Psychiatric Association and used by mental-health providers to diagnose patients and clear them for treatments and medications with insurers, this new edition, the DSM-5, included a change allowing the newly bereaved to be diagnosed with major depression. To qualify, a patient need only have experienced at least five symptoms on a checklist — including sadness, sleep disturbance, loss of concentration, and decreased appetite — for at least two weeks.

Proponents defended the change by noting, as did psychiatrist Ronald Pies in the Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience journal, “DSM-5 recognizes that bereavement does not immunize the patient against major depression, and often precipitates it.”

Cacciatore was a leader in the chorus of critics who spoke out in more than 100 journal articles around the world; she wrote a passionate blog post against the new DSM and its “medicalized approach to human suffering” that went viral in 2012.

“I’ve had so many circumstances where somebody’s baby just died, and before they even leave the hospital they’re being written a prescription for an antidepressant, a sleep aid, and a benzodiazepine [for anxiety]. You mix that with a little bit of alcohol, and you’ve got a really dangerous situation,” she says. “We’re pathologizing what it means to be human and to grieve.”

“God is nearest the brokenhearted.” — Psalms 34:18

There is a Sedona hiking trail — one of countless footpaths in this trekking hot spot — called Brewer Trail, just a few miles east of the care farm. It snakes up through Arizona ash and cottonwood trees, creosote bushes and prickly pears, edging along a steep drop for a dramatic 2-mile climb. It’s one of the spots where Cacciatore takes clients, both alone and in groups, for barefoot hikes — one of her many out-of-the-box therapy methods, which also include exceedingly long talk sessions, guided meditations, grief journaling, and reconnecting with nature through mindfulness exercises.

“One of the defining characteristics [of trauma] is that you sort of leave your body and disconnect,” she explains, “and the idea is to get back in your body, feel safe in it, and start reconnecting with as many things as we can.”

Borreani, the Massachusetts mom who lost two of her children, and who came here to work with Cacciatore over the summer as a last-ditch effort to emerge from her “deepest, darkest place,” says she barely noticed the stunning landscape here upon her arrival, but that she experienced a major shift by the end of her therapeutic week.

“The mindfulness has helped me appreciate the world again,” she says. “When I first got [to Sedona] I was like, ‘whatever.’ By the end, I had to stop and look at every mountain.”

Sedona, known far and wide for its spiritual vortexes and healing energy, is certainly an ideal setting for Selah. That became particularly clear on the afternoon I went with Cacciatore, shoes and socks left in our wake, up the Brewer Trail.

She calls this “metaphorical” work, and it’s no mystery why: On the climb, tiny stones feel jarringly sharp and make my eyes water, while larger lumps hitting a particular spot in my arch make me yelp from pain and wonder if I can even go on. Fine sandy patches are gifts, soothing as baby powder, and I linger through them, taking time to look out into the shockingly alien expanse, remembering the rawness of my own long-receded anguish, which is never hard to conjure.

The lesson, of course, is that you can navigate pain, but not avoid it.

And then there’s the hopeful part of the metaphor: that the longer you keep at the exercise, the more you become accustomed to how it feels.

At the top of the lookout, where the smooth, sun-warmed sandstone soothes your feet with sweet relief before your return to the rock-strewn path, the rolling expanse of orange and brick red formations seems to stretch as far as the sea.

This part is perspective. And connection.

This is what people find here, and back down the path and across town at Selah. It’s what Chemakoh likely glimpsed as he was led up and out of the canyon where he had spent his life suffering. It is the moment when a new, hopeful reality might click for the first time, and when those mired in grief might first begin to understand that it is possible to survive.

“Part of the problem is that when we go through a catastrophic loss, there’s an existential loneliness that comes over us. It’s like, ‘How can anyone possibly know the depth of my pain?’” Cacciatore had explained earlier, on one of our first walks to the horse pen.

“And yet you come to a place like this, and despite these animals being a completely different species and having a completely different experience of trauma and grief, you can feel a connectedness. And it makes that loneliness just a little less salient. It’s one more little piece of connection to something real. And that’s really potent for us as humans.”

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

5-year-old survivor of Texas church massacre just wants Christmas cards for the holidays

Meet the woman who guides parents through their darkest days

Texas students were forced to do ‘bear crawls’ at school, and the internet has a lot of feelings

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.