Are cicadas dangerous? What makes this double brood so special? We asked an expert.

As the trillions of cicadas are emerging in states across the Midwest and Southeast this year, USA TODAY caught up with Gene Kritsky, a cicada expert and professor in the Department of Biology at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati, Ohio to get your cicada questions answered.

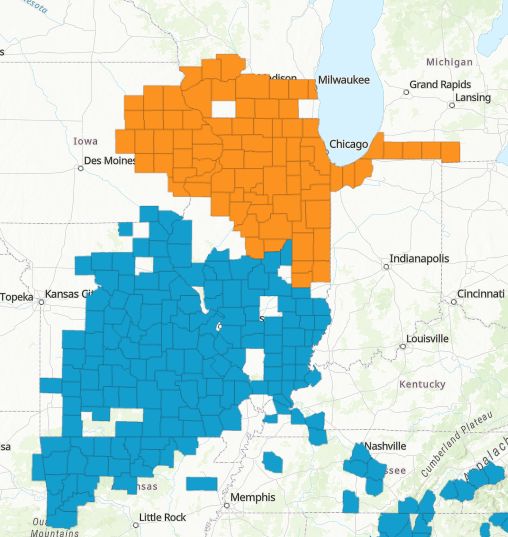

Seventeen states are expected to see cicadas from two separate broods: the 13-year Brood XIX and the 17-year Brood XIII. They have been waiting underground for the right conditions to emerge, feed, mate and die, when the next generation will then head underground to start the cycle all over again.

This double brood event is special because its been 221 years since they emerged at the same time ? in 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was president. They will not emerge together again until 2245.

The cicadas are coming: Frustrated Americans should join them by screaming, too.

Questions and answers have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What makes the double brood this year so special, and different from the broods we’ve seen emerge in previous years?

Kritsky: What’s interesting this year is that we have two different broods emerging: 17-year cicada Brood XIII emerging in the same year as the 13-year cicada Brood XIX. There are 12 distinct 17-year cicada broods in the U.S., and only three 13-year broods.

Every 200-something years, this double emergence will happen about three times. What makes this one special is that the two broods have a potential overlap. We know that they are adjacent to each other; the most recent mapping showed they will be buddying up next to each other. Some of the research I've done in 1998 showed they did overlap, but that was when they came out independently. Some people have gotten excited thinking this overlap will mean double the cicadas, but unfortunately that’s not what’s going to happen.

This will be the extreme southern end of the distribution for Brood XIII, and for Brood XIX, it’s the northern end of its distribution. They’ll be coming close to each other, but cicadas don’t fly up to a mile in an emergence year. We won’t know (if they overlap) for sure because you can't tell the broods apart. We can have cicadas in the overlap zone but we wont know for sure until we go back and map for Brood XIII and Brood XIX in 13 and 17 years.

What makes up a cicada brood? How do they know if they’re part of the 13- or 17-year broods?

Kritsky: The brood is like a class, like a graduating year, and they’ll have a reunion in 17 years. The current numbering system started in 1893 with Charles Marlatt. There were other competing numbering systems prior that was just a number, but it was very complex and difficult to figure out what was what.

For simplicity, Marlatt said every 17 year cicada that emerges in 1893 is Brood I, and so on, with numbers 1-17 reserved for 17-year cicadas. For every 13-year cicada in 1893, that number was Brood XVIII, numbering 18-30. Once that number was in place, they found 15 established broods: 12 17-year broods and three 13-year broods.

It’s very common for cicadas to come out one year early or four years early. They can also come up four years late. We know where these stragglers probably came from, because if there’s only one brood in that area, and we have cicadas coming off-cycle, then they have to be coming from this brood.

Are cicadas coming out earlier than expected or are they right on track?

Kritsky: They all don’t come out on one night, and it requires the right soil temperature. It turns out, if you’re on a hill facing south, that soil will get to 64 degrees Farenheit before the trees on the north will. It takes about two weeks for all the cicadas to emerge. The critical thing is soil temperature and we’ve been getting warmer springs. Cicadas are insects of climate, they respond to climate and are coming out earlier.

The first adult cicada that was reported to Cicada Safari was reported on the evening of April 14. That’s almost more than a week earlier that our data from three years ago. In a lot of places, including Georgia, parts of Tennessee and Alabama, they came out April 14.

The following week, they came out in North Carolina and South Carolina, and that is earlier than they did with Brood X (in 2021). We’re now seeing large numbers emerging in southern Missouri. Brood XIX has not started coming in large numbers in Illinois yet, however there are pockets in southern Illinois where adult cicadas are being reported.

Talk about the Cicada Safari app. Have you noticed that people seem to be excited and are logging cicada sightings in their area?

Kritsky: We’re approaching 18,000 photographs (on the app) this year, and over 218,000 downloads total. Brood XIX is the largest from a geographic perspective, which means a lot of people who had the app from Brood X are now reporting cicadas from XIX. They don’t overlap, but they’re in the same region.

The whole idea is to get parents to go outside with their kids, watch cicadas develop from immaturity to adult and try to trigger an interest in science. I’ve often said that periodical cicadas are the gateway drug to natural history.

What are the environmental impacts? How do periodical cicadas affect the world around them when they come up?

Kritsky: Periodical cicadas do an awful lot of good for the Eastern deciduous forest where they live. Not because they do it every year, but because of these pulses of nutrients. When they emerge from holes in the ground, those holes are like a natural aeration. Those soils have a lot of clay, and those holes are beneficial for the trees. They are a pulse of prey for all sorts of predators: dogs, cats, raccoons, birds, snakes, turtles, deer, etc., because those predators have more food to feed their offspring, we can see a pulse of population the following year.

When the female lays her eggs on the terminal branches of trees, that causes those branches to break and the twig dangles and leaves wither, and that’s a natural pruning. It means there will be more flowers on the tree next year, and there will be a pulse of seeds next year. Lastly, as they finish mating and the female lays her eggs and they die, their carcasses start collecting at the base of trees. As they decay, they’re putting nutrients into the soil around the trees.

Are cicadas dangerous to humans or pets?

Kritsky: No, not at all. Some vets have warned to limit dogs on eating tons of cicadas because it could lead to bowel obstruction. I’ve given my cats the opportunity to have a little cicada treat every once in a while. You shouldn’t be afraid of cicadas. They may be big but they don’t bite, don’t sting, don’t carry disease. If you’re lucky enough to live in an area where they’re emerging, go out at night and watch them transform. It’s an amazing phenomenon to observe.

Where do cicadas spend their time underground?

Kritsky: They only come out below trees. Trees are crucial to their life cycle. Eggs are laid in tree branches, and when those eggs hatch, newly-hatched nymphs fall to the ground and burrow underground quickly. For the first few weeks they’re feeding on grassroots, and cicadas puncture the xylem tissue carrying water to tree leaves. By New Year’s Day they are 8-10 inches below the surface, and that’s where they’ll be for the next 13-17 years. They don’t cause any damage to the trees underground.

When and where will the next 13- or 17-year cicada brood emerge?

Kritsky: The next brood is Brood XIV, which will be in 2025 and parallels a lot of the areas where Brood X was. There will be a pocket out east in Maryland and Virginia, in Pennsylvania and in the Midwest in Northern Kentucky, southern Ohio and southern Indiana.

2024 cicada map: Check out where Broods XIII, XIX projected to emerge

The two cicada broods will emerge in a combined 17 states across the Southeast and Midwest, with Illinois and Iowa expected to see both.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Expert talks 2024 cicadas: Are they dangerous? Did they come early?