A college LGBTQ center disappeared. It wasn’t the only one.

As grief consumed the University of Houston last year, one place on campus became a sanctuary.

Staff at the LGBTQ resource center, a cozy second-floor office furnished with a red sofa and a shelf full of comfort food, sprang into action after the unexpected death of Corey Sanders, a 23-year-old who helped lead a club for queer and transgender undergrads.

Sanders loved to sing, said Jamie Gonzales, the center’s former interim director, but he was shy about it. She urged him to step out of his comfort zone and perform at his lavender graduation, a special ceremony for LGBTQ seniors.

She never got the chance to hear him. Sanders died suddenly from a diabetic coma last October, according to the medical examiner. The university couldn't confirm whether students were officially notified about his passing.

But at a memorial outside the LGBTQ resource center a few days later, a crowd spilled into the hallway. The center was Sanders’ “second home,” his friend Kaitie Tolman said.

A year later, that haven of safety and acceptance is gone, too.

As the first anniversary of Sanders’ death approached, the letters L, G, B, T and Q – which adorned the wall outside the door for years – were stripped from the entrance. They came off at the direction of university administrators, who indicated the center would be disbanded after Texas’ Republican governor signed a law banning offices dedicated to “diversity, equity, and inclusion” – or DEI – at the state’s public colleges and universities.

Earlier this year, Texas and Florida’s conservative governors signed two of the most sweeping anti-DEI bills nationwide into law. The bills, brainchildren of two influential conservative think tanks, were part of a flurry of recent legislation that was shuttled through numerous statehouses in tandem. The effort entrenched college DEI programs as a culture-war issue in American politics.

Unlike the efforts in Texas and Florida, many of the anti-DEI bills introduced across the country didn’t succeed. In other states – including North Carolina, North Dakota and Tennessee – less stringent bans, applying only to mandatory diversity training, passed.

Yet even those laws are raising questions about how they could affect the lives of vulnerable college students. In the meantime, LGBTQ centers at several colleges across Texas and Florida are being shuttered, with little clarification from college leaders.

Caught in the crosshairs of it all is a generation of young people, for many of whom getting to college – and staying there – is already a miracle.

Fighting for LGBTQ+ rights: How a Christian transgender man increased his faith by taking on religious schools

'Page not found': LGBTQ centers disappear

Two years ago, the Office of LGBTQ+ Initiatives and Allyship at Florida Atlantic University was going strong. Its staff were hard at work for their students, helping some figure out how to change their legal names during an April 2021 panel.

A professor at Florida Atlantic University, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, told USA TODAY that in recent months, the university’s resource center “just disappeared.” A web search for the school’s LGBTQ resource center now yields a “page not found” error.

FAU’s communications office did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

In April, Texas Tech’s Office of LGBTQIA Education & Engagement held a party for Lesbian Visibility Day. Just a few months later, its Twitter and Instagram accounts are inactive. Texas Tech’s communications office did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

There are only about 250 professionally run LGBTQ centers on campuses across the country today, according to the Postsecondary National Policy Institute. That’s just a fraction of the nearly 4,000 colleges and universities in the U.S. The proportion is less than 7%, despite the fact that a fifth of college students surveyed in 2020 by the Association of American Universities said they identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, queer, or questioning.

Institutions in Texas have until January 2024 before the new anti-DEI law can be enforced. Florida’s law, however, took effect in July. The legislation tasked the state’s 17-member Board of Governors, which oversees the public university system, to develop guidelines for implementing it.

USA TODAY obtained a copy of draft regulations recently sent by the board to public universities for comment. The draft rules, first reported by the Chronicle of Higher Education, do little to clear up any confusion. They continue to define DEI programs as those promoting “differential or preferential treatment of individuals,” including on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation.

The draft regulations were not released publicly, yet another indication of how colleges and universities are quietly grappling with the new rule – a strategy that has, so far, obscured the law’s impacts, according to Carlos Guillermo Smith, a senior policy adviser with the LGBTQ advocacy group Equality Florida.

Smith said his group has been monitoring the situation. And they’re alarmed by the silence from colleges.

“These programs exist for a reason,” he told USA TODAY.

Research shows LGBTQ college students face persistent barriers to getting into college and staying there. Family rejections, an increased likelihood of homelessness and a tougher federal student aid process all contribute to an oppressive environment, said Jason Garvey, an education professor at the University of Vermont.

“Legal guardians hold a disproportionate amount of power over the lives of queer students,” says a study he and other researchers published last year in the Journal of College Student Development.

Filling out forms necessary to afford college, such as the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, can pose a major challenge. An analysis of Education Department and survey data indicates that queer and trans students are more likely than their heterosexual peers to have a lower socioeconomic status.

That’s where LGBTQ centers come in.

If queer and trans students get to college, LGBTQ centers make those students feel safer, according to a 2016 article in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence. And when they feel safer, they’re more likely to stay in school – and graduate.

“It is through these services and these communities that students are retained academically,” Garvey said. “We need to start treating them for the value that they bring.”

'Completely different from high school:' How colleges are making space for LGBTQ students

A decade in the making

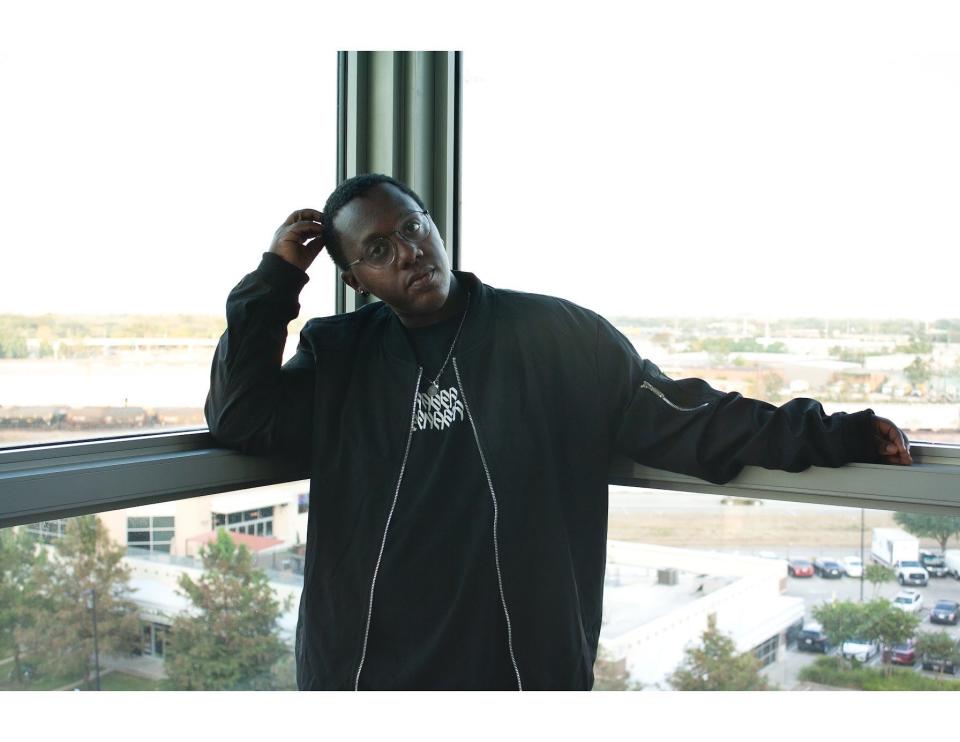

When Dane Ashton first learned about the University of Houston center, he had a Sharpie in his hand.

It was 2016. He was in his freshman dorm room, and his roommate glimpsed him blacking something out from his university ID. The target of his anxious blotting? His legal name. For about a month it had been glaring at him – one of those uncomfortable reminders that can easily become rote, but never stops being painful, for trans people like himself.

Go to the center, he remembered his roommate saying. The staff there would help him make the change.

He took the advice, and by the end of the day, Dane Ashton’s ID said Dane Ashton.

His situation was a classic example of the type of work Lorraine Schroeder did every day. The University of Houston is a big school, with more than 40,000 students, and bit by bit, the challenges queer and trans young people brought into her office weighed on her. She loved her job, but after more than a decade leading the center, the burden of that work got heavier. She retired in 2021.

“I just emotionally couldn’t take on anymore,” she said.

Schroeder, who has a master’s degree in clinical psychology, started the center at UH in 2010. Back then, her position as director was just half-time. The then-provost agreed to let her share space with the women’s resource center.

She had a small budget then, only about $10,000. As far as staff, it was just her, plus a few federal work-study students.

One of her first ideas was simple. She hosted brown bag lunches on Mondays. They were a way for students to “make connections with other LGBTQ students” or “just hang out with friends,” she wrote in an old funding request.

Ten to 20 students showed up regularly. The lunches were especially important for the freshmen, who often didn’t know any other queer or trans students on campus yet.

Building community – that was priority No. 1. She wanted to create a space where LGBTQ students could “let down their guard.”

“Gender identity, when you’re first trying to figure it out, is a big thing,” Schroeder said.

Regardless of which pronouns her students wanted to use that day, she honored them. Some tried out different names. As they progressed in their journey of self-discovery, some even volunteered to share their stories – “whichever parts they wanted,” in her words – at events put on by the center.

Each time they did, they got “more and more in touch with accepting themselves,” she said.

As her students grew, so did the center’s budget. She fundraised and scraped for more money from administrators. Three years in, she was hired full-time. By fiscal year 2016, she had turned that initial $10,000 budget into a roughly $140,000 one, school records show.

Over the years, the center hosted LGBTQ ally trainings for hundreds of people. Like many other schools, the staff organized a special graduation ceremonies just for queer and trans students. There was even a special library with LGBTQ books.

Then, a few months ago, a decade’s worth of momentum came to a halt.

A flier prompts outcry

“In Accordance with Texas Senate Bill 17, the LGBTQ Resource Center has been disbanded,” read a sign posted outside the center in August.

Outcry rose swiftly. University administrators first said the sign was posted prematurely. Then Daniel Maxwell, the interim vice chancellor for student affairs, confirmed the center would close Aug. 31, along with the university’s Center for Diversity and Inclusion.

In its place would be a new “Center for Student Advocacy and Community.” Part of the new center’s mission, administrators wrote in a Sept. 1 message, would be to “address the wide-ranging needs of our students.” No one appears to have lost their job at the LGBTQ center completely, but five employees were moved into new roles as a result of the change, university spokesperson Shawn Lindsey said in an email.

In a message to students Aug. 23, Maxwell said the university remains committed to supporting students.

Some of them see it differently. Kaitie Tolman, the president of GLOBAL, the student LGBTQ group on campus, said the university seems to be going overboard to comply with the new law. She’s not alone in that sentiment.

“These schools are really jumping the gun,” said Johnathan Gooch, a spokesperson for the LGBTQ rights organization Equality Texas.

Tolman said she and other students met with UH administrators several weeks ago, and she wasn’t satisfied with what she heard. She started a group called “Free U of H,” which is planning a campuswide walkout later this month to protest administrators’ handling of the closure.

Tolman was close friends with Corey Sanders, the student who died last year. After his sudden passing, she remembers sending an email to the LGBTQ center, asking if she could use their space to plan a memorial.

Within 15 minutes came a response. She didn’t need to organize anything, the staff said. Give them three days, and they’d handle it all.

A private college nearby steps in

Weeks earlier, a similar chain of events had played out on a neighboring campus. In the wake of another student’s death, Rice University’s Queer Resource Center held office hours for people to grieve, according to Cole Holladay, a queer junior who uses they/them pronouns and was friends with Ryan Dullea, the 19-year-old student who died.

Both were chemistry majors. Both were LGBTQ. The two bonded instantly.

“Losing someone I think really reminded me how important it is to create that community,” Holladay said.

This summer, when Holladay heard UH’s LGBTQ center was closing, they knew they had to do something. So Holladay, the co-president of the university’s LGBTQ club Rice Pride, offered honorary membership not just to UH students, but to students across Texas whose resource centers might be on the brink of closing.

Unlike at UH, Rice’s center is entirely student-run. And unlike at UH, Rice is a private school, so it’s not affected by the new state law.

Schools mum on their 'game plan' for LGBTQ centers

“I’m not quite sure what the game plan is,” said Shane Windmeyer, the founder of the LGBTQ advocacy group Campus Pride. He’s been in touch with schools across both Florida and Texas, he said, who are wrestling with how to save their centers.

USA TODAY reached out to five public universities in Florida and five in Texas, plus the University of Houston, to ask about the status of their LGBTQ centers. All of them have had designated centers or offices specifically for LGBTQ students. Only a few responded to emailed requests for comment.

A spokesperson for Texas A&M University, Kelly Brown, said the university is “working toward compliance” with the law before January. Administrators are considering how to support all students including those in the LGBTQ community, before taking any action.

Brian Davis, a spokesperson for the University of Texas at Austin, said in an email the school expects to receive more guidance from the UT system on how to implement the law in the coming weeks.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ press secretary, Jeremy Redfern, said in an email the DeSantis administration hasn’t been quiet about its “goal to eliminate DEI from higher education and refocus our institutions on their core mission: pursue truth, promote rigor in academic discourse, and prepare students to be citizens of this republic.”

A spokesperson for Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

LGBTQ centers date back decades

The first LGBTQ center dates back to 1971, according to Campus Pride. More were founded in the ‘90s on the heels of the death of Matthew Shepard, a University of Wyoming student who was tortured and murdered in a hate crime 25 years ago this month. It's one of many reasons why October is the month of LGBTQ Center Awareness Day, a holiday that now falls on the same week as the anniversary of Corey Sanders' death.

Shepard’s murder galvanized the LGBTQ rights movement on college campuses, said Jeff Maliskey, the director of the University of North Dakota’s PRIDE Center. Maliskey wrote his dissertation on the history of LGBTQ student activism at his university.

In North Dakota, queer and trans college students in the 1990s had to organize for their rights, he wrote, “out of necessity,” because his university was failing to protect them from discriminatory laws.

Those circumstances reminded him of the hue and cry across Texas and Florida today. Progress, he said, came only when students pushed for it.

“Students bore that responsibility,” he said. “But where was the institution?”

Zachary Schermele is a breaking news and education reporter for USA TODAY. You can reach him by email at [email protected]. Follow him on X at @ZachSchermele.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: A university LGBTQ center disappeared. It wasn’t the only one.

Solve the daily Crossword