Confederate names are being scrubbed from US military bases. The list of ideas to replace them is 30,000 deep.

WASHINGTON – For decades, the Pentagon has venerated Confederate officers who betrayed their oaths and waged war against their country to uphold slavery by placing their names on property from military bases to ships.

The effort to scrub the Confederacy's legacy from bases, streets, barracks, gyms and ships gained momentum during the racial justice movement that sprung from the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020. It survived a veto from then-President Donald Trump, who wanted to retain the honors in the name of "history."

Federal law, enacted Jan. 1 after Congress overrode Trump's veto, now requires that change by 2024.

A federal commission, led by retired Adm. Michelle Howard, has been surveying the military's vast holdings to determine the scope of change needed. It's likely that hundreds of names of those who voluntarily served the Confederacy attached to bases, streets and other facilities will be changed. Commissioners have held public meetings and solicited recommendations for new honorees – and nearly 30,000 suggestions have poured in.

For many, the change is as welcome as it is overdue.

Retired Army Maj. Gen. Dana Pittard, who is Black, recalls choosing his Army assignments to avoid posts that bore the names of Confederate officers who had committed treason.

"There's a reason we don't have a Fort Benedict Arnold," Pittard said, referring to the Revolutionary War officer who sold out to British forces and whose name has become synonymous with treachery.

"They acted against their oath as officers, the United States Army, against our country. I appreciate the fact that we're moving in a direction where we're really looking at the honor and what that means as far as our values as a nation, and the values of the U.S. Army. And I like where it's going as far as alignment."

The most visible changes

Some of the famed Army posts Pittard sought to avoid will be among those whose names will change. They include Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, N.C., known as "Home of the Airborne and Special Operations." It was named in 1918 for Braxton Bragg, a West Point graduate and Army soldier who went on to lead Confederate troops.

The other forts that honor Confederate officers are A.P. Hill, Lee and Pickett in Virginia, Benning and Gordon in Georgia, Polk in Louisiana and the Army's largest post, Fort Hood in Texas. Fort Belvoir, just outside Washington in Virginia, may also have a name change. It does not honor a Confederate general but bears the name of a plantation where enslaved people were forced to work.

The Navy likely will be included. The Maury, an oceanographic survey ship named for Navy Cdr. Matthew Fontaine Maury, probably will receive a new name, Howard recently told reporters. Maury left the U.S. Navy for the Confederacy.

Some names, however, are outside the commission's charge and won't be changed. Camp Beauregard, named for a Confederate general, is an Army National Guard installation and belongs to the state of Louisiana. The Navy's aircraft carriers USS Carl Vinson and John Stennis bear the names of lawmakers who backed segregation.

The commission will have other judgments to make. Howard indicated that a portrait of Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee that hangs at West Point honors his service there as superintendent before the Civil War and would be outside its mission. A portrait of Lee in his Confederate uniform, unveiled at the U.S. Military Academy in 1952, would be better hung in a museum than in a federal building, she said.

Whom could bases be named for instead of Confederate leaders? List of heroes

The commission has received nearly 30,000 recommendations for name changes, spokesman Stephen Baker said. The deadline for submission is Dec. 1.

Commissioners will decide names based on merit, not popularity. Howard did note that some candidates for commemoration have been repeatedly suggested. They include:

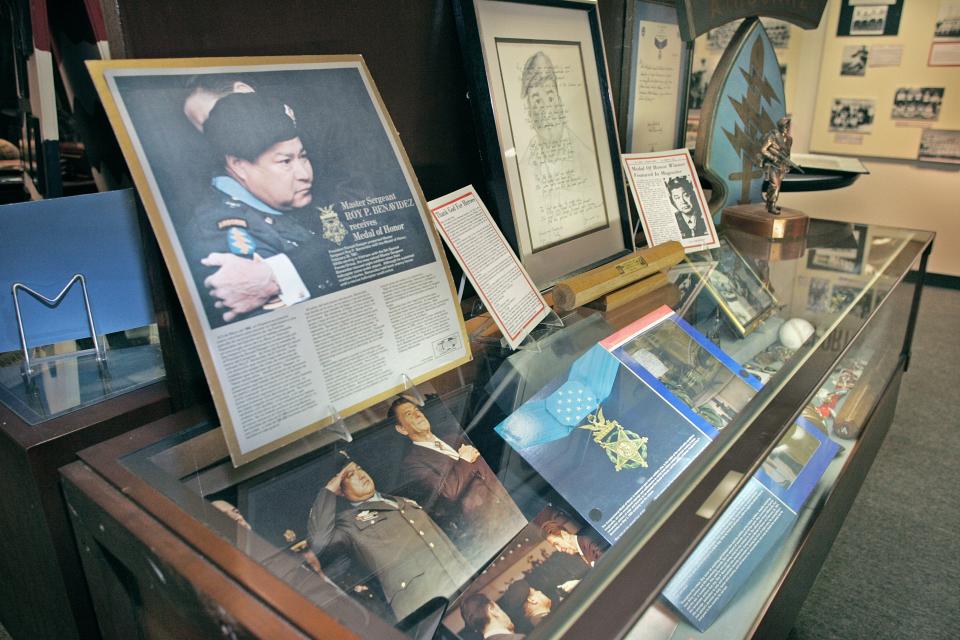

Army Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez. On May 2, 1968, Benavidez volunteered to rescue a 12-man team trapped in dense jungle in Vietnam. Dropped by helicopter, he ran to the men through gunfire and took wounds to his right leg, face and head. He rallied the surviving soldiers, dragging and carrying the wounded and dead to the aircraft. The helicopter crashed after its pilot was killed. Benavidez, who had been recovering the body of the team's leader and secret papers, was wounded again, taking bullets to his abdomen and grenade fragments to his back. He is credited with saving the lives of at least eight men.

"During the six hours of continuous operations, Benavidez suffered a broken jaw and 37 bullet and bayonet puncture wounds," according to the Army narrative of his action. "He was so mauled that his commanding officer did not believe he would live long enough to receive the Medal of Honor, so he nominated him for the Distinguished Service Cross instead, because the No. 2 award would take less time to process."

Years later, the Army nominated Benavidez for an upgrade. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest award for bravery. Benavidez died in 1998.

Troy Mosley, a retired Army lieutenant colonel and author, supports replacing Hood's name with that of Benavidez.

Gen. Roscoe Robinson. Robinson was the Army's first Black officer to be promoted to four-star general, and his name could replace Fort Bragg, Mosley suggested, where he commanded the 82nd Airborne Division.

Hal and Julia Moore. Lt. Gen. Hal Moore has been memorialized in a book and film for his leadership during the battle of Ia Drang in 1965, the first major battle between U.S. and North Vietnamese troops. Moore received the Distinguished Service Cross for his battlefield heroism, which was detailed in the book "We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young" and was made into a film starring Mel Gibson.

Julia Moore's efforts to support the families of troops killed in that battle prompted the Army to change the way it makes death notifications. The Army replaced the telegrams delivered by taxi drivers with a team of soldiers who notify family in person.

Code Talkers. At Fort Gordon, home of the Army's Signal Corps, Mosley suggested honoring Native Americans who delivered messages enemies could not decipher. Army Private Joseph Oklahombi was a World War I Choctaw "Code Talker" was one such soldier.

"I'm proud of the military's recognition that merit and willingness to serve are what matters most," Mosley said. "We have an opportunity to reflect that, not just talk it. This is a base named after a Native American who did some outstanding things, or this is a base that's named after a woman or a Black American and the struggles they had to go to serve their country."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Confederate officers' treason to be scrubbed from military base names