In Congress, time — again — for soul searching over abortion

Rep. Tim Murphy, R-Penn., a member of the House Pro-Life Caucus, said on Thursday he would resign his seat over reports that he had recommended an abortion to a woman with whom he was having an extramarital affair. It’s not clear why he thought he had to quit, however, since just three years ago an equally ardent opponent of abortion for other people, Rep. Scott DesJarlais, R-Tenn., a physician-turned politician, won reelection after it came out that he had paid for two abortions for his wife, and suggested an abortion to his mistress, one of his former patients. Pro-life voters are extremely forgiving toward those who agree with them. Family Research Council President Tony Perkins, who has described the work of Planned Parenthood as “the murder of tiny children,” chided Murphy for — what would you think? Gross immorality? Criminal solicitation? No, “inappropriate personal behavior” and its “public ramifications.”

Here’s a thought experiment: What would Perkins have said about a congressman who asked his lover to kill her husband? Would pro-life voters reelect an official who drowned his children, instead of aborting them? I recognize the difference, as I believe most Americans would, but by the terms of the pro-life argument, these amount to the same thing. I respect the right of abortion opponents to take a moral stand, but as a matter of policy and law, the pro-life movement keeps getting tangled up in its own contradictions, exemplified by one of the last votes Murphy cast in Congress, in favor of the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act.

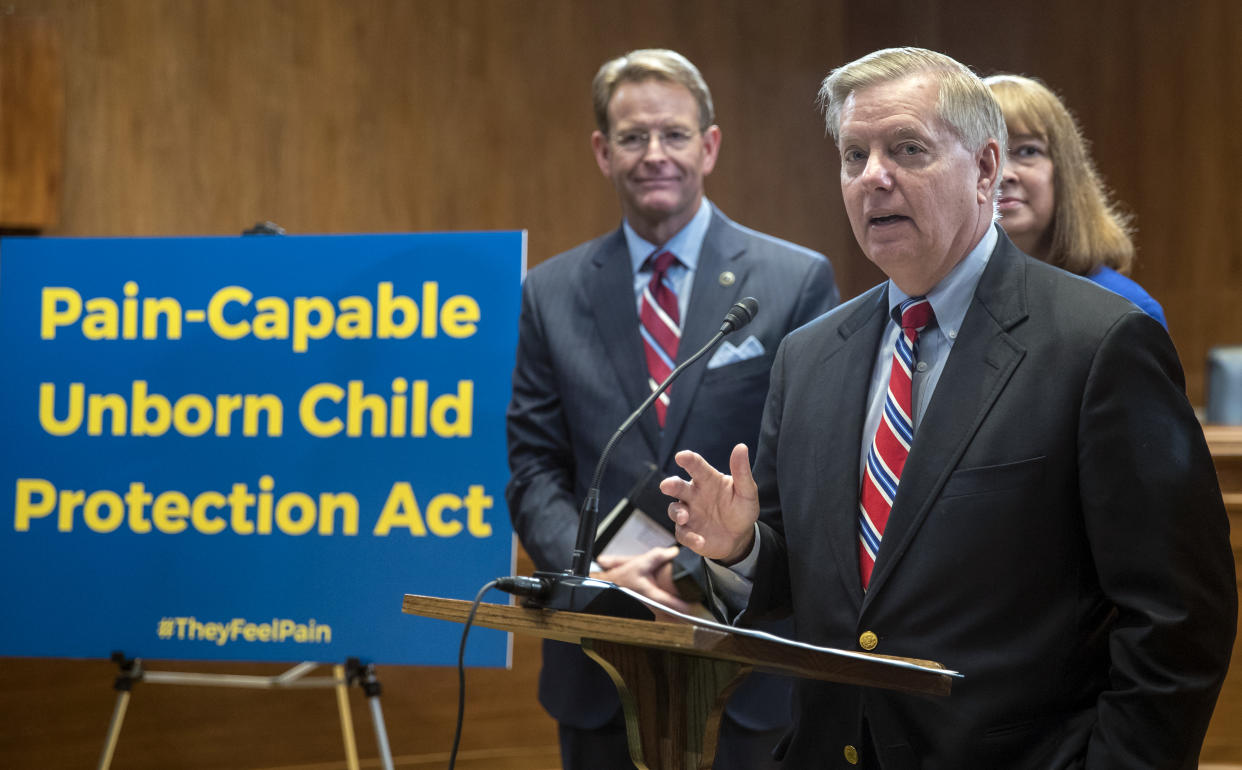

The bill, the latest attempt to impose a federal ban on abortion (with limited exceptions) after 20 weeks, passed on Tuesday on a party-line vote. On the very day Murphy turned in his resignation, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., introduced the bill in the Senate, and President Trump has said he would sign it. But two years ago, Senate Democrats blocked an almost identical bill, which is still considered the most likely outcome this time.

The bill is a vehicle for demonstrating the compassion that their opponents say Republicans lack, since it puts the emphasis on the fetus’s subjective pain, rather than its absolute right to life, based on its possession of a soul. The latter is, in fact, the position of many, probably the majority, of right-to-lifers, notably including Alabama’s former Chief Judge Roy Moore, the Republican nominee to replace Jeff Sessions, who in 2014 wrote:

“Legal recognition of the unborn as members of the human family derives ultimately from the laws of nature and of nature’s God, Who created human life in His image and protected it with the commandment: ‘Thou shalt not kill.’”

But as a political or legal proposition, that argument is lacking. It won’t persuade unbelievers, or people who construe their faith’s teachings differently, or a majority of the Supreme Court on any reasonable reading of the First Amendment, except Moore’s. Hence the bill’s emphasis on setting an objective, utilitarian standard for outlawing abortion, based on the age at which “pain receptors are present throughout the unborn child’s entire body and nerves link these receptors to the brain’s thalamus and subcortical plate.”

But even the bill’s sponsors admit this is a subterfuge. The people championing a 20-week ban don’t think abortion is OK at 19 weeks, or at 19 days or 19 minutes. They acknowledge that abortions after 20 weeks are so rare — 1.3 percent of all abortions, according to a 2009 government study — that it’s not going to save a lot of “babies.” They look on it as an exercise in consciousness-raising, in getting the public to think about abortion in their preferred light. “To encourage others to consider or support further legal protection for the unborn, one is almost required to make the case that at 20 weeks, an unborn person is able to feel pain,” Kimberly Ross wrote on the conservative website Red State. “Only then does abortion somehow seem worse.”

More cynically, it’s an effort to force Democrats facing election next year to take a vote that might hurt them. “We are preparing for 2018 Senate elections,” Marjorie Dannenfelser, head of the anti-abortion Susan B. Anthony List, has explained. “If we come up short, which is likely … what we’re doing is we’re building that Senate up to a 60-vote margin.”

The premise that a fetus can experience pain at 20 weeks is controversial in its own right. The bill incorporates in its “findings” medical data to support that claim, but the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists disagrees, asserting as settled fact that the ability to perceive pain as pain (distinguished from mere touch) begins at the start of the third trimester. You could argue that this is a philosophical argument as much as it is a scientific one. No moral person seeks to inflict pain, but whatever sensation the fetus experiences is momentary and leaves no memory because it is, afterward, dead. The mother, on the other hand, still has most of her life ahead of her, and the purpose of an abortion is to allow her to live it without the obligation to carry, deliver and raise a child she does not want. Looked at that way, stripped of the religious component, I think it’s clear which way the balance of human happiness tilts. As long as they don’t try to write it into law, anti-abortion advocates can argue, and their opponents can disagree, that nothing justifies the pain inflicted on the fetus, or that the mother would later regret an abortion, or she would in time learn to love the child, or that an abortion poses a hypothetical risk to her future health. But it should be clear by now that their real agenda is stopping a practice that offends their religious beliefs.

Twenty weeks, as it happens, has a special significance for the right-to-life movement, which has been focused in recent years on pushing back the nominal threshold of viability, the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb (with intensive medical intervention). The Supreme Court has, broadly speaking, viewed viability as the point at which the state’s interest in keeping the fetus alive can outweigh the mother’s privacy right to an abortion. In the 1970s, when Roe v. Wade was decided, that point was believed to be the start of the third trimester. But by 1992, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Court acknowledged that medical technology had advanced it to about 24 weeks.

The sponsors of the pain-capable bill are trying to plant a marker at 20 weeks — mendaciously, because (as the bill itself acknowledges) the age of viability has nothing to do with the onset of pain sensation. There’s good reason to suspect they are hoping to benefit from the resulting confusion. The last time this bill came up, two years ago, Dannenfelser of the Susan B. Anthony List lobbied for it by bringing around a sprightly 3-year-old named Micah Pickering, and advertising his near-miraculous birth and survival at 22 weeks. This time, Micah, now 5, is back as the “face” of the bill, and in the meantime his reported fetal age at birth has been pushed back to 20 weeks. Who says there are no miracles any more?

Because there are two different ways of calculating fetal age, both may be technically correct, but there is a reason why 20 weeks might serve Dannenfelser’s purposes better. The conventional method of calculating “gestational age” is to date it from the mother’s last menstrual period. But, of course, the embryo only begins to develop after fertilization — typically, although not invariably, about two weeks later. Until the advent of fetal ultrasound there was no easy way for doctors to determine this “post-fertilization” age. But the bill stipulates 20 weeks “post-fertilization,” a nuance that might well escape many women, and even their doctors. A woman at 20 weeks, measured the usual way from her last period, might believe she was past the window for an abortion, when in fact her fetus is only 18 weeks post-fertilization and still eligible under the law.

Like other social causes — gun control comes to mind, from the other side of the aisle — the movement to end abortion has been swallowed up by process, turned into a livelihood for lobbyists and political professionals who measure progress by seizing tiny tactical advantages and scoring symbolic victories. The fetal-pain bill is in that sense the mirror image of proposed legislation that has seized the imagination of Democrats: a bill to ban the sale of the “bump stocks” that turn semi-automatic rifles into functional machine guns. The bill, which even its advocates admit wouldn’t make more than a tiny difference in the statistics on gun deaths, was inspired by the massacre last week in Las Vegas. As it happens, Republicans were also sensitive to the implications of that tragedy. They, of course, drew the lesson that we have to ban abortion.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: