Is Cory Booker for real?

NEWARK, N.J. — The old woman walked outside in her bathrobe and curlers to shout at the man who might be president.

“Senator Booker!” she called out to him.

Cory Booker spun around and saw the woman standing on the stoop of her squat three-story apartment building.

“Oh my gosh!” he said. “How are you? I haven’t seen you in the longest time!”

The woman was incredulous.

“What are you doing over here?” she exclaimed.

“Just walking around the neighborhood,” said Booker. “I love that robe. Look at that.”

Her name is Stephanie. They apparently have known each other for a while. With a warm smile, she explained why she rushed out in her early morning finery.

“I just looked out the window and I said, ‘That’s Senator Booker!’”

Booker, who stands six-foot-four, is a hard man to miss. His bald head sits atop the agile, sturdy frame of a former college football player. And he’s a familiar face to anyone with a television. Booker’s been touted as a potential presidential candidate virtually since the day he was elected mayor of Newark in year 2006. It’s a city with about 280,000 largely African-American and Latino residents — and a tough reputation.

“You know, I still live right off Martin Luther King [Boulevard],” Booker told Stephanie.

He named a street about five blocks away. She had heard Booker was her neighbor in Newark’s Central Ward, but hadn’t believed it.

“Somebody told me that and I said, ‘He don’t live down here,’” Stephanie said.

Booker explained that he travels to Washington on Mondays and is usually back in New Jersey three days later. He walked through the neighborhood with Yahoo News late last month to show off the streets that birthed his political philosophy and the “proud things” he did here as mayor.

One of them was right across the street.

“I love our park,” Stephanie said.

“Yes. Isn’t it nice?” Booker replied. “We follow through. That was the promise we made. Remember?”

“I know. I know. I know. I know,” she said before offering him advice for his return to Washington. “Keep on fighting Trump.”

“Amen,” said Booker with a laugh.

Walking through New Jersey with Booker means frequent encounters with his fans. They are clearly aware their former mayor might run for president.

“2020, Mr. Booker! 2020!” shouted one passing driver.

“Our next president right there!” said another, as he pumped his horn in celebration.

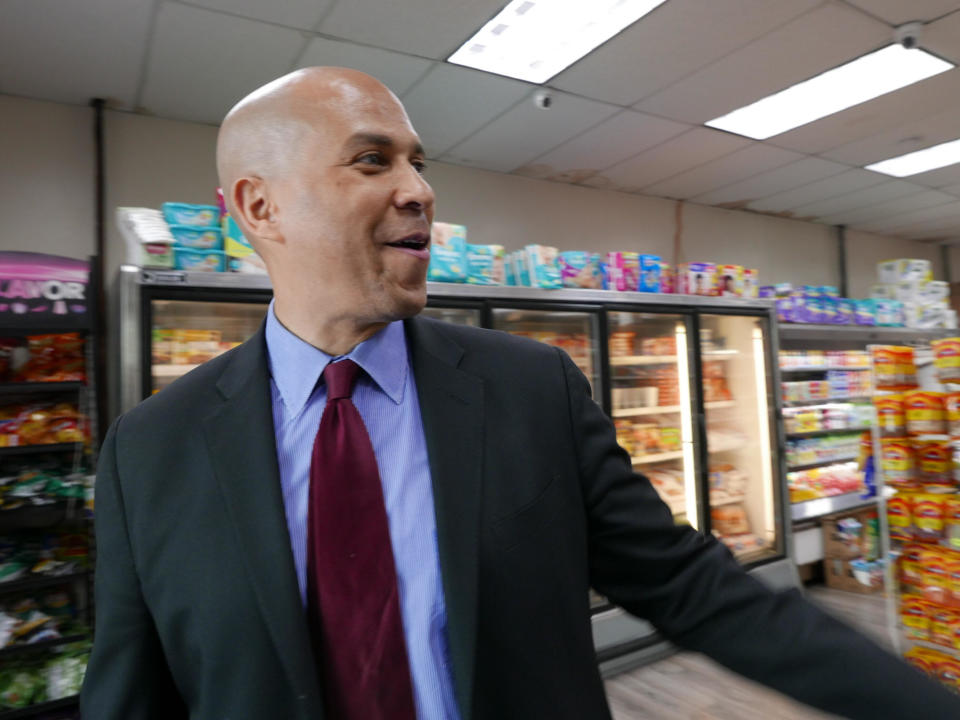

Booker got a similar greeting when he walked into a bodega around the corner from his house.

“Yo! Presidente!” said the man behind the register.

And it’s not just in Newark. In the hallways of Capitol Hill and at the speeches he gives around the country, Booker is regularly urged to mount a White House bid. It happens so often that he’s got something of a standard response.

“Thank you for that encouragement!”

When pressed about a presidential campaign by Yahoo News, Booker admits he’s going to mull the possibility.

“Look, my focus right now is two things; my own reelection and making sure we’re in a strong position for that and the 2018 elections,” Booker said. “I think, that passes, I’ll sit down and give a hard consideration about a lot of folks that are talking to me about doing something else.”

Booker’s term — he was elected in 2013, in a special election after the death of Sen. Frank Lautenberg, and then again in 2014 — ends in 2020. In the meantime, he’s become an in-demand campaign surrogate for other Democrats. In the past year, Booker has traveled to at least 11 states to stump for his colleagues.

So far, Booker has strenuously avoided any key early primary states that would fuel presidential speculation. But in an interview, Booker let slip that he is planning one trip that might raise eyebrows: a “red state farmers tour.” It’s the kind of thing that screams White House run, but Booker insisted “it’s not going to be a public listening tour.”

“We’re going to do it and not tell anybody were doing it,” he explained, adding, “We’re not going to be doing it with lots of media coverage.”

The reasons for the presidential buzz surrounding Booker are clear. Whenever Booker hits the campaign trail, he is a potent weapon. His rise has largely been propelled by his inspiring personal story — and his unique ability to tell it.

Asked about Booker’s future, David Axelrod, the veteran Democratic strategist and former top adviser to President Obama, sees Booker as an “exceptional political talent” who is a real potential 2020 contender.

“I think he is a brilliant guy; big-time personality, interesting thinker, and an at times spellbinding presenter and … obviously, a really good story. So, I take him seriously,” Axelrod said.

Axelrod currently leads the Institute of Politics at the University of Chicago. He recently hosted Booker there, and the strategist left with the impression that Booker’s flair for the dramatic can sometimes go “a bit too far” and reach a place where the senator “sacrifices a sense of authenticity” for “performance.” Axelrod offered up a classic piece of baseball lore from the early days of Dodgers pitching great Sandy Koufax as advice for Booker.

“Some catcher … told him, ‘You know you are a great pitcher … and you throw the ball 100 miles an hour, but if you threw it at 97 and got it over the plate you’d be untouchable,’” recounted Axelrod.

“I think that Booker is a great, great talent. … I think that he’s in public service for the right reasons, but he probably could take three miles off his fastball, and get the ball over the plate, and be even better,” added Axelrod.

Indeed, the captivating narrative and presentation that has inspired support for Booker has also provoked skepticism, including fears from progressives about his close ties to donors from Wall Street and the pharmaceutical industry. There are also substantive questions about his record in Newark and in the Senate.

Booker has in many ways mastered the art of retail politics. He has a boundless energy that he credits to a vegan diet supplemented by iced tea and his newest discovery, intermittent fasting. He knows just when to deploy a dad joke, fist bump, broken Spanish, a lesson from one of the many religions he’s studied, or a warm embrace. Booker is also a gifted orator. His speeches are crafted from what he calls “riffs,” including tales from his own life and anecdotes that have touched him from people he’s met or read about. Working without a script, Booker turns these set pieces into symphonies of rising emotion and soaring inspiration with his voice alternately breaking and booming before rapt audiences.

The Cory Booker origin story is a staple of his oratorical arsenal. His parents were pioneering black executives at IBM who were active in the civil rights movement. They were able to raise Cory and his brother in the wealthy New Jersey suburb of Harrington Park, with the help of housing activists who worked with the family to force unwilling property owners to sell them a home.

When Booker tells it, this isn’t just a tale of defying injustice. Booker calls the story a “conspiracy of love” and paints himself as the “physical manifestation” of the kindness and decency of those who helped his father as a poor young man and later in the face of housing discrimination. Booker sums it up with the words of a man he often quotes, Martin Luther King Jr.

“This was the lesson of my childhood, that we all are connected,” said Booker. “As Martin Luther King said, we are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a common bond of destiny. That injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Booker constantly returns to King’s legacy and teachings to discuss modern problems and his own ideals. But he doesn’t just channel King by echoing his values. Booker’s impassioned delivery has deep echoes of the black church tradition that shaped the civil rights icon. And both Booker and King can provoke a similar reaction from supporters. When we saw Booker present his personal story during a speech at the Parkinson’s Policy Forum on March 20, he left the ballroom full of activists on their feet. Some were in tears.

It’s a typical reaction. But these sermons do leave some wondering whether the emotion could possibly be genuine.

An aide to a senior Senate Democrat told Yahoo News about listening to one of Booker’s speeches. Booker wept on stage and had much of the audience joining him. The staffer was shocked when the senator abruptly left amid the applause.

“I’ve seen him give that speech five times — and each time he cried,” the senator said.

Booker began his community work attending college at Stanford. “I wanted to make a difference in the world. … I felt like I had all of this privilege,” he told a group of high school students.. “I was working in a place called East Palo Alto and found my calling. I wanted to do big things.”

Booker went on to earn a law degree at Yale and then to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship for an honors degree in American history. At Oxford, the decidedly non-Jewish Booker helped run a chapter of Chabad House and picked up biblical wisdom and Yiddish witticisms that still pepper his speeches.

Then comes the final chapter in the Cory Booker origin story.

“Before I even graduated from law school, I decided that I was going to move to the most dangerous neighborhood I could find in the city I loved,” Booker told the students.

In 1997, his final year of law school, he began working — and living — as a tenants’ rights advocate in Newark, about nine miles from Manhattan. The once-thriving city had seen steep drops in population and wealth, especially after the notorious riots in 1967.

Through his work in Newark, Booker met Virginia Jones, who led the Brick Towers tenants’ association in one of the city’s most troubled public housing complexes. Booker eventually moved in to an apartment there and, he says, Jones pushed him to run for city council.

This story is one of Booker’s main speech riffs. “I always say I got my BA from Stanford but my PhD on the streets of Newark,” Booker likes to say.

Booker also regularly recounts lessons and maxims passed down from Jones. She taught him that “hope is the active conviction that despair will never have the last word.”

In 1998, Booker, who was then 29, won a seat on Newark’s municipal council. He quickly began displaying the media savvy that would become a hallmark of his career, earning attention far beyond the city by moving into a tent and going on a hunger strike to protest crime.

Booker had a film crew by his side when he first ran for mayor in 2002. The subsequent documentary, “Street Fight,” captured his ultimately unsuccessful bid to unseat Mayor Sharpe James, who led a local political machine for two decades. Booker gained exposure as a crusader against corruption, but also saw some people questioning his authenticity.

James and his allies attacked Booker with a series of wild allegations, including that he was Jewish and a Republican. There were also insinuations Booker, a bachelor, was gay. That last accusation would stick with Booker through his ascent to the Senate.

Booker has addressed the gay rumors by saying, “So what if I am?” But he has dated women, most recently the poet Cleo Wade. When asked about Wade, Booker declined to comment. Wade did the same in a recent interview with the New York Times.

Booker made it to City Hall on his second attempt in 2006. After becoming mayor, he quickly became a national figure with an early presence on Twitter, where he promoted his own hands-on do-gooding: shoveling snow, delivering diapers, welcoming people into his home during a hurricane, and even helping to rescue a woman from a burning building.

The heroics led to fantastic press. However, the outsized characterization brought a unique political problem. As one of his many national headlines in the Washington Post put it, Booker was “almost too good to be true.” Advisers knew people could be skeptical.

“It can be frustrating when you’re working for him because, with any politician, people are cynical,” one former Booker campaign staffer said. “They believe that there’s a difference between your private self and your public self. But he is who he is. It’s almost unbelievable, but he is.”

Booker’s soaring speechmaking added to the implausibility.

Van Parish, who managed the first mayoral campaign, explained how the lofty rhetoric could be a “challenge” for Booker.

“I would say he’s for real,” Parish said. “What people are going to be skeptical about is, Where is the proof in the pudding? What has he done? Where is the manifestation of all of the rainbows and unicorns? He’s so good talking about the challenges that we face, but what has he done?”

Booker is aware of his doubters, but says his record speaks for itself.

“This is the beautiful thing about this point in my career … and folk in this community know it,” said Booker as he walked through the city. “Stuff I hear, ‘Everything I say is sizzle and no whatever.’ And I’m like, Wait a minute. Now you have a 20-year career to analyze.”

His seven years leading Newark had highlights and lowlights.

As mayor, Booker’s burgeoning brand as a “social media superhero” coupled with his charisma and connections from his elite education brought support from celebrities and business leaders including Oprah, Bon Jovi, hedge funder Bill Ackman, and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. The star power helped Booker attract an influx of donations and development to Newark.

Booker wooed major businesses, including Panasonic and Prudential, to the city. Newark saw its first major new grocery stores and hotels in years, new office towers, a $150 million real estate and educational complex. Booker notes all of this occurred against the backdrop of the national recession and a fiscal crisis that saw a quarter of the city’s employees laid off. After years of decline, Newark’s population grew. And along with the corporate donations and development, after inheriting a deficit Booker found savings in the city budget and left it balanced for the first time in a decade.

Not all of the change during Booker’s tenure was positive. While the crime rate initially dropped sharply, it ticked back up in 2010, a situation Booker attributes to widespread police layoffs that he blames on New Jersey’s former Republican Gov. Chris Christie. And the new real estate developments and revitalized downtown have raised the specter of gentrification with Newark even getting dubbed a “new Brooklyn.”

While walking through the city with a correspondent from Yahoo News, Booker acknowledged rising rents are a concern that comes with growth. Booker said he tried to address this by requiring affordable housing, educational facilities and jobs for locals to be part of new projects in Newark. Booker doubled the number of affordable housing units in the city during his tenure. He described his philosophy as “inclusive development.”

Nevertheless, for a progressive Democrat stepping onto the national stage, Booker’s past reliance on corporate development and philanthropy could be a liability. But Booker is unapologetic.

“I would challenge any of those people to be mayor of a city in a recession. … Your job is to help people and by any means necessary,” said Booker, adding, “Live where I live for a year and tell me you wouldn’t do whatever it took.”

One of Booker’s grandest gestures caused the biggest controversy of his mayoralty. In 2010, Booker teamed with Christie and Facebook billionaire Mark Zuckerberg to launch a $200 million plan to overhaul the Newark’s school system. The effort, which Booker dubbed a “bold new paradigm,” was backed by donations and launched on an episode of Oprah Winfrey’s talk show. It included a new teacher-evaluation system aimed at increasing accountability and an expansion of charter schools in the city. But with students being moved to charters, many district schools were closed, which angered many residents.

Booker’s $200 million school reform effort was chronicled in a 2015 book by journalist Dale Russakoff called “The Prize: Who’s in Charge of America’s Schools.” While she depicted Booker as well-intentioned, Russakoff was sharply critical of the way changes were communicated to city residents and how much of the money went to highly paid consultants. The book led to a spate of negative headlines questioning whether Newark’s schools really improved after the influx of cash.

Last October, Harvard’s Center For Education Policy Research released a detailed report analyzing Booker’s schools overhaul. The assessment found that, “on net, by the 2015–2016 academic year, Newark students had seen a significant improvement in the rate of growth in English and no significant change in math.”

Booker believes the effort was judged too quickly and feels vindicated by the new research.

“It was a success!” he said of the school reform push.

Booker has won over some of his critics in recent years, notably Newark’s current mayor, Ras Baraka, who has developed what allies of both men characterize as a strong partnership with Booker.

During Booker’s time in Newark, Baraka represented the South Ward on the council. It was Sharpe James’s base and a hotbed of anti-Booker sentiment. Baraka was a prominent opponent of the schools plan.

Baraka and Booker’s improved relationship was on full display in February, when the former mayor appeared alongside his successor as he filed petitions for reelection.

In a phone call with Yahoo News, Baraka said Booker has done “an outstanding job as United States senator” in opposing Trump administration appointments and in advocating for Newark in Washington. He cited Booker’s successful push to include “opportunity zones” in the tax reform bill last year. The program, which evolved from a proposal by Booker and South Carolina Republican Tim Scott, provides tax benefits for businesses that invest in census tracts designated by governors as areas in need of growth. Baraka even has kind words for his former foe’s tenure as mayor.

“He laid the foundation for a lot of things. People began to look at our city differently because of Cory’s presence here,” Baraka said.

Baraka’s campaign has conducted polling for his reelection bid that found Booker currently has a 78 percent approval rating in Newark. Booker even has the backing of John Sharpe James, the current South Ward councilman and son of Booker’s fiercest rival.

Not everyone is on board. Donna Jackson, a current council candidate and longtime Booker critic, calls the relationship between Booker and Baraka an “unholy alliance.”

Jackson was a Baraka supporter and staunch opponent of Booker’s school reform effort. During a phone call last week, she described the expansion of charters as an “onslaught” and argued the focus should have been on improving existing district schools rather than opening new ones.

When Booker ran for Senate in 2013, Jackson worked with his Republican opponent, Steve Lonegan, to raise more questions about Booker. She appeared alongside Lonegan at an event where he made the false claim Booker does not live in his house in Newark’s Central Ward. Lonegan and his campaign also revived the gay rumors about Booker, saying it was “kind of weird” Booker never refuted the allegations.

Booker defeated Lonegan, but more serious questions emerged during the Senate race. In 2013, the National Review published a piece that accused Booker of making up some of the dramatic anecdotes he deployed in his speeches.

Specifically, the magazine questioned whether Booker made up a man named “T-Bone” who featured in many of his trademark riffs. Booker regularly described T-Bone as a young man who threatened his life when he first moved to the Central Ward, but later became a friend. The National Review talked to a Booker ally who said the future senator once privately admitted that T-Bone was a “composite.”

Questions about T-Bone first popped up in 2007 when Newark’s Star-Ledger newspaper tried to find the man behind the riffs. The local reporters could find no evidence the nicknamed city resident was real. At the time, Booker said T-Bone was “1,000 percent a real person.” And there are multiple veterans of Newark’s police force who are willing to back Booker up on this point.

Anthony Ambrose, the city’s current public safety director, has worked in local law enforcement for more than two decades. He was a police officer in Newark and served as the city’s top cop under James, a position he lost when Booker took office. When asked by Yahoo News, Ambrose said multiple criminals in the city used the “T-Bone” alias so he “never doubted” the senator’s tale.

Jimmy Wright, who recently retired after a long career that included stints as a beat cop and homicide investigator, lived in Brick Towers at the time and witnessed an incident where Booker was threatened by local drug dealers. Wright said the men were angry over the increased police presence Booker brought to the neighborhood.

“I know for a fact that there were some guys that threatened Cory one day in front of the building. They were selling drugs. Basically, when Cory moved in, he messed up [their business],” said Wright.

Wright also said Booker worked to befriend the young dealers and “they ended up loving him.”

And Booker definitely does have relationships with some colorful characters in his Newark neighborhood. As he walked with Yahoo News, a man named Earl Best ran up to say hello. Best is a current city worker and former convicted bank robber who became known as the “Street Doctor” by delivering blankets, food and supplies to Newark’s homeless.

“This is a legend in Newark. The Street Doctor,” Booker said as the two men embraced.

“That’s my buddy!” Best said pointing at the senator.

The Street Doctor had some bad news for Booker.

“Your buddy died. Binky,” said Best.

He explained that Robin “Binky” Brown, a retired detective and longshoreman who helped produce a 2009 Sundance Channel documentary that featured Booker, had died the night before. Booker exchanged numbers with Best and asked to be apprised about Brown’s funeral.

“Keep taking care of the kids, man,” Booker said as the two men parted. “They look up to you.”

Booker says his connections with the people in his Newark neighborhood are vital to him on Capitol Hill, where a map of the Central Ward hangs over his desk.

“I just feel like, if I ever lose that, like the connections in my neighborhood, the connections in my city, the connections to urban spaces in New Jersey, I feel like I’m rudderless and rootless,” Booker explained.

Newark provides Booker with firsthand experience about the challenges facing the poor and people of color. But these issues aren’t unique to urban areas, Booker repeatedly stresses “whether you’re in Appalachia or Newark,” people around the country are dealing with “common pain,” including economic insecurity, water and air quality issues, gun violence and the opioid crisis.

“I’m the only United States senator that lives in what could be characterized as an inner city,” Booker said. “I’ve stayed rooted in the community. If all of our senators lived in pockets where there’s poverty and … the struggle for America was going on, I think it might be better for our country.”

These beliefs have led Booker to focus on justice in three areas — criminal justice reform, environmental issues and economic inequality.

But opponents question his legislative record.

“Before he launches his 2020 presidential bid, Booker might want to accomplish something in the Senate,” Republican National Committee spokesman Michael Ahrens said of Booker.

But as a member of the minority party, he has a steep hill to climb towards passing legislation. Besides adding the opportunity zone amendment to the tax bill, Booker also authored provisions including a ban on solitary confinement for juveniles in the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, a criminal justice package that has passed out of committee and has bipartisan support.

Booker has also worked with state and city politicians to help them implement versions of proposals that may be unable to pass Congress. Specifically, since he introduced the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act last year, a dozen state houses have introduced similar legislation. The act includes steps designed to improve conditions for women in prison, including giving them mentors and greater access to health care products. Three weeks after Booker introduced the act, the Federal Bureau of Prisons issued a memo calling for female inmates to have free access to tampons and pads, which was a key component of Booker’s legislation.

Even on matters where Booker has no chance of getting a law passed, he and his team believe he can play a valuable role raising the issue. Booker has become a leading advocate for marijuana legalization, and has proposed legislation to expunge federal marijuana convictions and penalize states where minorities have faced disproportionate rates of marijuana arrest and incarceration. He’s also behind legislation for a pilot guaranteed-jobs program and a package designed to address environmental issues in poor communities.

Having a conversation with Booker means hearing an endless stream of data points he’s picked up, including anecdotes from people he’s met and facts absorbed through what is clearly a voracious reading habit. The health issues facing people dealing with poor environmental conditions are a favorite topic. He rattles off details about lead exposure, the health risks of refineries and tropical diseases in the United States. Booker said his concept of environmental justice was informed by things he’s seen in Newark as well as fact-finding trips to Southern states.

Some observers think Booker’s Senate agenda is meant to win over wary progressives, who are suspicious of the way he has courted campaign contributions from Wall Street and the pharmaceutical industry. Last January, Booker provoked outrage from the left when he joined a bipartisan group that included Republicans in opposing a proposal from Sen. Bernie Sanders designed to lower drug prices. After adding steps to address safety concerns, Booker joined Sanders and worked with him to announce a new bill that would legalize drug imports from Canada.

Ahrens, the Republican Party spokesman, predicts that tacking left could kill any chance Booker has to be a viable presidential candidate.

“Given how much the base dislikes him, Booker’s going to keep adopting radical policies that will destroy his presidential aspirations, like his massively expensive and totally impractical plan for the government to provide jobs for everyone,” Ahrens said.

Booker certainly has friends in the two major wings of the divided Democratic Party. A source familiar with Sanders’s thinking said the former presidential candidate clearly “enjoys working with Cory on the issues.” The source pointed to a chummy joint appearance the pair made on Facebook Live last month to discuss marijuana legalization. “Booker has come around on some good progressive policies,” the source said, mentioning his support for Medicare-for-all universal health care. And Sanders, whose socialist brand of politics was dismissed by some Democratic moderates, also appreciates Booker’s large platform.

“There is value to having someone who is perceived by the Beltway as more ‘mainstream’ supporting these ideas,” the source said.

Sanders’s presidential primary rival, Hillary Clinton, also has a positive relationship with Booker. A top Clinton campaign source said Booker was her second choice for a running mate, and multiple sources confirmed it was a tight decision.

Booker’s chance of successfully leading a presidential ticket of his own hinges on his ability convince a cynical electorate that he’s more than just an incredible speechmaker. And he’ll have to prove the stories in those speeches — and perhaps more important, the emotions behind them — are real.

Amid that challenge, Booker has an unofficial validator in the form of Ruby Quocko, a Newark woman in her 70s. Quocko is the daughter of Virginia Jones, the tenant activist who inspired Booker’s political career. In a phone call with Yahoo News, Quocko defended Booker’s sincerity.

“If you don’t know the man, you can’t judge him,” Quocko said of Booker. “What you might think is insincere is because you don’t know him.”

Quocko said she jokingly calls Booker her “little brother” because he was like an “other son” to Jones. Booker has stayed in touch with the family since her mother’s passing.

“Being mayor never stopped him from being around my mother,” Quocko added. “When my mother became ill, Cory was there to visit her quite often.”

Quocko said Booker was with Jones when she died, “just like a family.” He also took care of Jones in her final days.

“When my mother was in the hospital he saw to it that she had her own private room and was well taken care of,” said Quocko.

Amid the grief, Cory Booker was still being Cory Booker. Quocko said he walked around the hospital and visited with other patients.

“He stopped into their rooms and asked them how they felt,” she said. “He didn’t care who it was.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump admits he reimbursed Cohen for Stormy Daniels ‘hush money’ payment

Anti-Semites on the ballot: GOP ‘condemns’ three contenders with racist views

As House wraps up Russia inquiry, top Dem on Senate probe says there’s no end in sight

After relief debacle, Puerto Rico’s governor looks for political revenge in Florida