Curtis Hill was a rising GOP star before the groping allegations. Can the grassroots save him?

Editor's note: This is part of a series of profiles on each of the six Republican candidates for governor.

Read our profiles on Mike Braun, Brad Chambers, Suzanne Crouch, Eric Doden and Jamie Reitenour.

Update: Curtis Hill's jury trial in the civil lawsuit regarding the 2018 groping allegations, originally scheduled for the week of April 8, was canceled.

Corrections and clarifications: A previous version of this article misstated the nature of the Indiana Supreme Court's finding in its attorney discipline case against Hill. The court found he committed criminal battery.

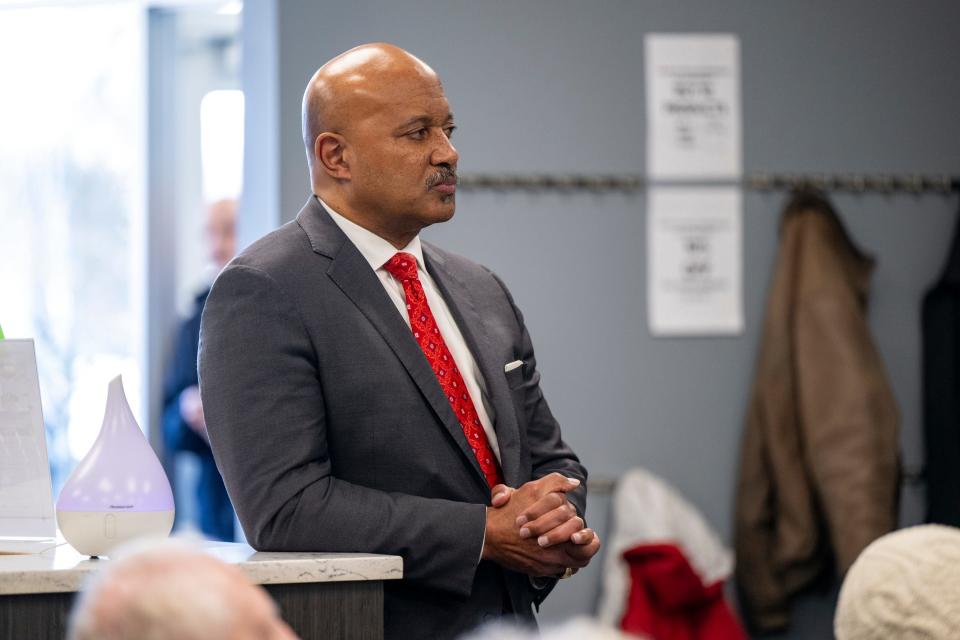

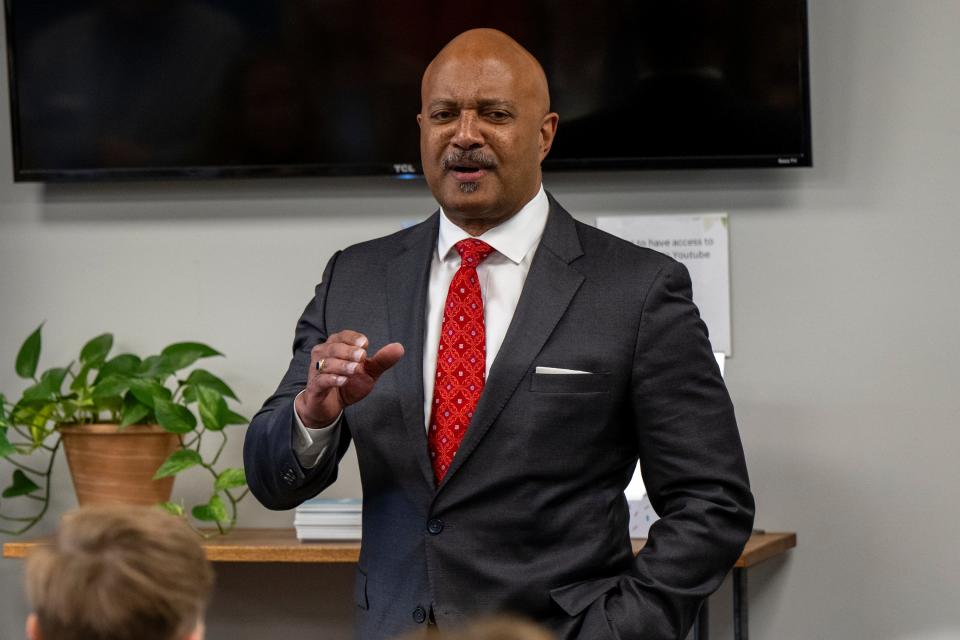

A seasoned public speaker, Curtis Hill opens with a hook.

"How many of you have given your consent to the state of Indiana to sell your personal data?" he asks a crowd of about 50 squeezed into an Indianapolis chiropractic clinic on a recent Tuesday evening, before even mentioning his own name. There's some reluctant hand raising and mumbling infused with laughter ― they know what the answer should be, but they want to see where Hill is going with this.

Hill hits them with the reveal: The Bureau of Motor Vehicles made $26 million last year from selling Hoosiers' personal data to third-party companies like insurers and auto dealers. (A new state law requires the BMV report its sales after a WRTV investigation drew attention to the issue.)

"You cool with that?" he asks, to a smattering of emphatic "no" answers.

The people are rapt and Hill is in his element. He gives a 30-minute speech peppered with jokes, impressions, interactive questions, and anecdotes solidifying his image as the fighter who, running for governor of Indiana, will stand up to his own Republican party and defend freedom and transparency. As he talks about lost faith in institutions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the crowd ― mostly white and middle-aged or older ― nods slowly and silently.

The former attorney general, tough-on-crime Elkhart County prosecutor and son of a trailblazing civil rights activist could always command an audience. Nearly a decade ago, he was the rising star of the Indiana GOP, someone widely envisioned as potentially Indiana's first Black governor one day. Groping allegations by four women who worked at the Indiana Statehouse severely dampened those prospects: His own party condemned him, and as the MeToo movement raged, so did much of the public.

But Hill's star power today is recognized among a new crowd: a grassroots base that awakened in 2020, provoked by their outrage at mask and vaccine mandates and perceived government overreach. Hill put himself at odds with the rest of the Gov. Eric Holcomb administration during that time, issuing a legal opinion that Holcomb didn't have the authority to mandate mask-wearing. And for several earnest attendees at Hill's meet-and-greet at the chiropractic clinic in northern Indianapolis, hosted by Stand For Health Freedom, that very action was the spark that ignited their support for him.

He's largely running from behind in a field of six Republicans, including U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, former Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers, Fort Wayne entrepreneur Eric Doden and political newcomer Jamie Reitenour. In a winner-take-all race with so many undecided voters, Hill hopes to capture just enough voters dissatisfied with the status quo of the party machine.

"Republicans are supposed to be about limited government and about freedom," Hill says, arriving at his core pitch. "I don't like what my party does. I'm here to tell you about it because it's not about me fixing it, it's about you fixing it. And you can't fix it unless you know about it."

Indiana Governor candidate Q&A: Former Attorney General Curtis Hill on the issues

'The chosen one'

Hill's first electoral victory was a resounding one, and other victories would follow.

In 2002, Hill was a deputy prosecutor in Elkhart County running for the top job. His competition in the Republican primary was the chief deputy, who had the support of the outgoing prosecutor. But Hill campaigned aggressively, called for changes at the prosecutor's office and spent tens of thousands on billboards all over the county, the South Bend Tribune reported at the time. In what most observers expected to be a tight race, Hill won the primary with 60% of the vote, partly due to a remarkable voter turnout.

Curtis Hill prosecutor election

Article from May 8, 2002 The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana)

Elkhart City Council President Arvis Dawson, who was a councilor at the time, remembers a significant chunk of that turnout being Black voters who usually vote for Democrats.

"The African American community made the difference for him," Dawson said.

Hill's law-and-order message prevailed over the restorative-justice message of his Democratic opponent in the general election. He won the election with 78% of the vote, becoming the county's first new prosecutor in 28 years.

As prosecutor, he made good on multiple campaign promises. He turned the prosecutor job from a part-time gig to a full-time one and moved the office from its small home within a private firm to a new, shiny building on Main Street ― a necessary improvement to some, a vanity project to others. He spearheaded a multi-jurisdictional drug task force, and later, a homicide unit, which persist today. And he would continue to get reelected for three more terms.

Being tough on crime wasn't just a campaign slogan for Hill. In a case that gained international attention, he filed felony murder charges against the "Elkhart Four," a group of four young men held accountable for the death of their friend who was killed by a homeowner acting in self-defense during a botched burglary. The Indiana Supreme Court later overturned their convictions.

Hill was the type of prosecutor to handle the high-profile cases, like murders, himself, rather than treat the prosecutor's office like a managerial role, said Brad Rogers, an Elkhart County commissioner who was sheriff during part of Hill's tenure.

"Curtis was right in there in the trenches fighting for the people," Rogers said. "I wouldn’t want to be on the end of his interrogation."

At the 2016 Republican Party convention, Hill edged out two other serious competitors, including a former attorney general, to win the nomination after three rounds of voting.

Mike Murphy, a former state representative, remembers Hill's commanding presence at the convention, assigning his speech an almost Martin-Luther-King-Jr-like quality. It also helped, in this new Trump era, that he was a bit more of an "outsider" than his opponents, who also included a state senator and an assistant attorney general.

"He had a very impressive convention showing against a pretty talented group of people," Murphy said. "People were enthusiastic about him."

In the 2016 general election where Hill won 62% of the vote, 1.6 million Hoosiers turned out to vote for him ― about 90,000 more people than who voted for former President Donald Trump that year, and at the time, it was a record number of votes for any race in Indiana history.

Even before he was attorney general, many circles in Elkhart talked about him as a future superstar, Dawson said.

"He was their chosen one at one time," he said. "And then the thing happened."

Record as AG marred by groping allegations

Far more than his predecessors, Hill earned headlines as attorney general from day one.

While in office, he built a socially conservative national profile ― a trend Todd Rokita has continued ― weighing in on issues like national anthem protests and visiting the White House to meet with Trump on school safety issues. He caught flak for spending on office renovations and a new mobile office van emblazoned with his name. He took an oppositional stance to his own party on multiple issues, from the efficacy of needle exchange programs ― Holcomb signed a bill allowing local governments to establish them, and Hill thinks they are "bullshit" ― to CBD oil, which Hill declared illegal.

Midway through his term, in June 2018, an IndyStar investigation unveiled allegations from four women, including a state representative, who said Hill groped them at a post-legislative session gathering at an Indianapolis bar. A federal judge dismissed the subsequent lawsuit and a special prosecutor declined to file criminal charges, but the state Supreme Court Disciplinary Commission launched its own investigation. In 2020, that court decided Hill violated professional rules of conduct and committed criminal battery, and suspended Hill's law license for a month. Hill, then as now, vehemently denies the allegations.

That decision came down shortly before the 2020 Republican convention. Many leaders from his own party, including Holcomb and the party chair, called for his resignation, but Hill didn't budge. Hill narrowly lost the Republican nomination by state delegates for a second term.

"He was fatally damaged," Murphy said. "Nobody took him seriously anymore."

After the federal judge dismissed their civil lawsuit, the women filed in Marion County court; a jury trial was scheduled to take place beginning April 8, but the judge canceled the trial, indicating the case may be settled out of court. Former State Rep. Mara Candelaria Reardon declined to comment for this story; IndyStar's attempts to reach the other women were unsuccessful.

The damage to his reputation shows in his fundraising. Hill raised about $375,000 in 2023, a large chunk of that coming from individual donors, but trailing behind the multi-million-dollar coffers of his opponents like Braun, Chambers, Crouch and Doden.

Unlike these opponents, Hill hasn't made the airwaves with any ads of his own, nor has he been the subject of attack ads. And in the first independent poll of the governor's race, Hill polls next-to-last. As a result, he didn't qualify for one of the three gubernatorial debates held so far.

To a grassroots base, though, these can be selling points: These television ads are D.C. templates full of nationalized talking points, and he's here to cut through the B.S.

"The danger that we have in this whole process is that you've got these multimillionaires who are in the race buying this election," he told IndyStar while sipping a strawberry milkshake at the Sugar Factory in downtown Indianapolis ― a lunch spot he chose for its "impressive" menu and atmosphere, "except their choice of commercials is not very good," he said as a Chambers ad played on a large screen.

"They get on television, they saturate the market with ads that present a narrative that is contrary to the narrative of who they really are, and then the public, who only gets the opportunity to be exposed to our ideas through television, they get swamped with this stuff over and over. More commercial, more commercials. And so what are you going to vote for? Oh, I like this guy on the commercial."

His supporters, he says, seem to have moved on from the groping allegations. It simply doesn't come up.

"I think most people see that for what it was from a political nature and have moved on beyond it," he told IndyStar in December.

This certainly isn't unprecedented in today's era of politics. Republican primary voters, after all, have continued to throw their support behind Trump, despite a jury having found him liable for sexual abuse in the civil case of writer E. Jean Carroll.

"It’s kind of like a scar when you get a cut: It’s healed, but there’s always that remembrance that you’ve cut yourself," Rogers, the county commissioner, said. "I think people are willing to say it’s healed, but there’s probably a remembrance of the scar. He’s going to make sure he doesn’t put himself in that kind of situation again."

Jane Herin, 63, who attended Hill's meet-and-greet, said she wasn't sure what ended up happening in the case. What sticks in her mind is when Hill called out Holcomb for the mask mandates.

"I said, 'Hey this guy's got a spine,'" she said.

Many people at his meet-and-greet became interested in politics only as recently as the pandemic. Tammy Alexander, a 61-year-old hairdresser, wasn't allowed to work for seven weeks because her profession was not considered "essential," and she's been "paying attention ever since."

The role of race

One of Hill's earliest memories is the night white neighbors threw a molotov cocktail onto the roof of his family's house in Elkhart.

His father, Curtis Hill Sr., a postal service worker who also led the Elkhart NAACP and Urban League, was the first to integrate the northeast side of Elkhart, a white neighborhood. Curtis Hill Jr. followed certain rules growing up that he didn't realize the significance of until he was older: If he hit a ball into the neighbor's yard, that ball belonged to the neighbor. He wasn't allowed to walk the three blocks to school by himself; his mother drove him.

"When you are Black person living in America, there’s not a day that goes by, a moment that goes by that you’re not aware of your Blackness," Hill said. "Being aware of it doesn’t mean that it controls you. It’s just a part of the unfortunate dynamic that we have in this country."

The way through it, Hill believes, is by acknowledging the painful past out loud, forgiving one another for it and moving forward, together, even as it, he says, "sounds pollyannaish." To illustrate his point, he often tells a joke about a fictional math contest with a $25,000-prize. He asks, if you had the choice between three Asian people or three white people to be on your team, whom would you choose?

It's a hit with the crowd at the chiropractic clinic, who laughs knowingly.

"We need to be able to go through exercises like that, openly and boldly," he said. "We all judge people by race. Once we start understanding that, we can be a little bit more empathetic and start the process of healing. What we don't want to do is have this check-the-box mentality."

On the debate stage, he'll incorporate the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion acronym into a talking point: He's alright with diversity, but not over excellence; inclusion, but not over competence; equity, but not over fairness.

He wants to abolish Holcomb's DEI office because he sees the modern movement as one that promotes racial preferences. What some might see as a stark contrast from the views of his activist father, Hill sees as a more honest interpretation of the aims of the 1960s movement.

"My father was fighting for freedom and equality. He wasn’t fighting for preference," Hill told IndyStar. "There’s nothing by virtue of my father’s activism that was intended to divide us."

The Curtis Hill we don't see

Hill knows he comes off as stern, serious, perhaps intimidating.

But he's actually a jokester: His impressions at the meet-and-greet included Donald Trump (a decent one), P90X creator Tony Horton, even caricatures of familiar scenes in political ads: a guy in a hard hat walking through a factory (Braun, minus the hard hat, and a little bit of Chambers), a narrator saying he got his start mowing grass while the screen shows a generic lawnmower (Chambers).

Indiana governor's race: Many candidates, little time to grab voters' interest

The first time he and his wife, Teresa, met at Indiana University was at a Halloween party, where Hill dressed as a literal bag of trash: He stuffed a trash bag with newspaper, tried it at the top and stuck his head through.

"He was a poor college kid just like I was, and what was the cheapest?" she laughed. "He’s always been fiscally conservative, what can I tell you."

Many people know he's an Elvis impersonator on the side. He'll still do one off the cuff on demand; the last time he did the full ensemble, outfit and all was in 2017, Hill said.

He can rattle off the very first play he acted in, in the second grade: He played Timmy the Turtle in a play based on the tortoise-and-the-hare fable. The Hill family of 7 would act and sing in dozens of community theater productions together as the kids grew up.

It's been years since Hill traded community theater for political theater. The political stage held its own plot twists. When the groping allegations surfaced, strangers appeared in their driveway and harassed their children online, Teresa Hill said. As far as how it impacted Hill's career, Teresa Hill said they simply don't think that way ― Hill's career is in their God's hands, she said.

"We truly do not dwell on things like this," she said. "We don’t get our instruction from the world; we get our instruction from the Lord."

About Curtis Hill

Age: 63

Home: Elkhart

Education: Business and law degree from Indiana University.

Family: Wife, Teresa, and five children.

Previous experience: Indiana attorney general 2017-20; Elkhart County prosecutor 2002-2016

Support from outside groups: Hill has endorsements from Stand for Health Freedom, Hoosier Conservative Voices, Young Conservatives of America and former national security adviser General Michael Flynn.

Contact IndyStar state government and politics reporter Kayla Dwyer at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @kayla_dwyer17.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Curtis Hill, stained by groping allegations, captures new grassroots base