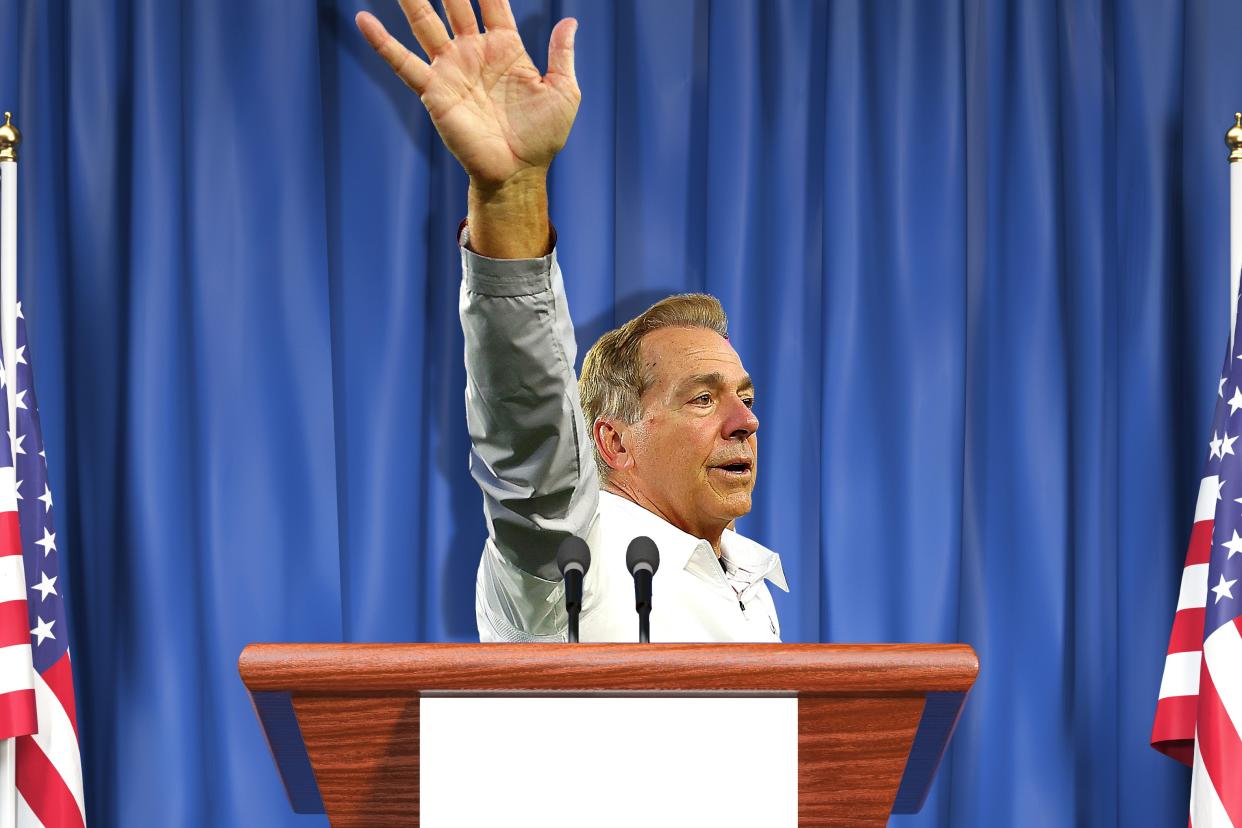

If Democrats Want to Beat Tommy Tuberville, It’s Clear Who They Have to Recruit

Nick Saban has no apparent reason to run for political office and several reasons not to. But in the next few years, Democrats in Alabama will have no choice but to put relentless pressure on the recently retired University of Alabama football coach to do so. Maybe, they’ll need to hope, he will get bored enough in retirement to consider it, or maybe he can be browbeaten into feeling the insatiable itch of public service.

Over two weeks in late January, pollsters from the market research firm YouGov surveyed 532 registered voters in Alabama and found Saban narrowly leading Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville, himself a former college football coach at Auburn, in a hypothetical matchup for Senate in 2026. The polling group, which shared its data with Slate, found Saban leading with 42 percent of the vote to 39 percent. The poll’s margin of error is plus or minus 4.9 percent, meaning it’s best to think of Saban and Tuberville as tied, the pollster said.

Saban’s competitive posture against Tuberville is in stark contrast to how other Democrats fare. Former Sen. Doug Jones trails Tuberville 52 percent to 27 percent, a more expansive margin than Tuberville’s 60–40 win over Jones in their 2020 race. (Jones was quite popular in Alabama for a Democrat, but to win his seat, he needed to run against an accused sexual abuser, Roy Moore.) YouGov also polled Tuberville against a “generic Democrat” and found the Republican leading with 49 percent of the projected vote to the generic Dem’s 32 percent. Only Saban was competitive. No candidates have yet announced a run to challenge Tuberville.

“Nick Saban looks like an extremely valuable recruit that Democrats should be considering carefully in this race,” John Ray, the polling director of YouGov Blue, the Democratic political research division that set up the survey, told me. “I base that on the clear signs of his strong personal constituency and on his relatively strong performance compared to others who Democrats might be considering.”

The first step, of course, is the unlikely one of getting Saban to do it. When the most accomplished coach in college football history retired in January, he had an eye toward getting a respite from the grueling grind of his profession. But even now, he has plenty on his plate. Saban just joined ESPN, where he’ll get paid well to go on TV a few times a week. A member of multiple exclusive country clubs, Saban plays to a 10.6 handicap index in golf and no doubt would like to get himself into the single digits. He co-owns a Ferrari dealership. Alabama even claims he’ll maintain a presence around the football program, ostensibly to smooth the transition to new coach Kalen DeBoer. What’s more, Saban has sometimes tried to paint himself as the opposite of politically engaged. The day after the 2016 election, he said he “didn’t even know yesterday was Election Day.” After that caused a stir, Saban said that he’d voted absentee.

But Saban has indicated over the years that he does care about professional politics and is at least a little bit—emphasis on “a little bit”—of a Democrat. The former coach, a native West Virginian, is a longtime friend of retiring Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin and endorsed him in his 2018 reelection. In 2022 Saban signed a letter urging Manchin to help pass voting rights protections, though Saban later clarified by way of a media leak that he did not support going around the filibuster. Saban said last year that college football players should be unionized and explained to an interviewer, “General Motors and the automotive industries had unions for a long time and they survived fairly well.” Saban is a registered voter in Alabama, but the secretary of state’s office doesn’t list a party affiliation. Saban’s agent, Jimmy Sexton, did not reply to emailed questions about whether Saban would have any interest in running or under which party affiliation.

However slight, Saban’s leanings were enough that his retirement prompted immediate Democratic wondering and wish-casting, including from the state party: Could the seven-time national champion be persuaded to challenge Tuberville, turning the 2026 Senate race into a coaching rematch of the Iron Bowl? Probably not. As Manchin put it: “You can put that out of your mind, because Nick won’t run. He would never run.”

Still: Democrats should make the pitch anyway, then make it again. When Tuberville ran, he demonstrated that a Republican in Alabama could win a Senate seat with two things: some name recognition from a coaching career and an endorsement from Donald Trump. Saban wouldn’t have the latter, but he built up striking popularity via the former. YouGov found that 81 percent of Alabamian registered voters have a favorable view of Saban, with 58 percent describing their view of him as “very favorable.” Trump’s overall favorability is 58 percent, Tuberville’s is 49 percent, and Joe Biden’s is 33 percent. Current Auburn head coach Hugh Freeze is at 30 percent. Auburn legend Charles Barkley is at 62 percent.

Saban is comfortably the most popular figure in Alabama public life. For now, that makes up for his status as a Democrat in a state full of Republicans. He leads Tuberville 75 percent to 6 percent among Democrats. Saban also has a 41–25 lead among independents. Tuberville’s lead among Republicans is 65 percent to 23 percent. That kind of crossover vote for Saban is consistent with a finding that 17 percent of Tuberville voters in his 2020 race against Jones say they’d pick Saban over Tuberville today.

That Saban would enjoy a personal advantage over Tuberville, notwithstanding their political parties, is unsurprising. Just about everyone in Alabama roots for either Saban’s Crimson Tide or Tuberville’s Tigers. But by the time of his Senate election, Tuberville hadn’t been the coach at Auburn for 12 years, and even during his career on the sidelines, he was unspectacular. Tuberville went 13–0 in 2004, a year when Auburn would’ve played for a national championship if USC and Oklahoma had not also had unbeaten seasons. But nearly every Auburn coach, including his two immediate successors, has had a year like that, and Tuberville found himself out of a job after a few years of mediocrity. He then coached and lived out of state before returning for his Senate campaign. Saban has loomed large in the state every day since Tuberville left. (Saban did recently buy beachfront property in Florida, though.)

Saban’s 10-point buffer ahead of a hypothetical “generic” Democrat caught Ray’s attention. “Typically, a generic candidate is a pretty good bellwether for the state,” he said, “and the fact that he overperforms to the degree that he does suggests that he has a strong personal constituency that he could capitalize on should he choose to run.” For some rough napkin math, getting 10 percent more of the vote share in 2020 would’ve put Jones in a dead heat with Tuberville. And that year, Tuberville had Trump on the ballot to boost Republican turnout, something he won’t have in 2026, a midterm cycle.

But the case against Saban is easy to make too. He is neck and neck with Tuberville right now, on the immediate heels of his retirement and at a time when almost nobody is saying anything negative about him. From the moment Saban entered the race, he would find himself bombarded with a Republican effort to tie him to the Democratic Party broadly. The GOP effort would be to get voters to forget about Saban’s national championships and think more about Chuck Schumer.

“If he chose to take on a race of this level of attention, it’s clear his opponents would try to make him seem like just another Democrat to the extent possible,” Ray said. “And the data suggests that if they were successful, that would hurt his candidacy.”

That can’t sound appetizing to Saban, who could (and almost certainly will) instead spend the next two and a half years playing golf, traveling, and doing TV spots. It may not even appeal to Democrats who are exasperated by Manchin’s voting behavior and think Saban would be a redux.

But given the near impossibility of any other Democrat contending for Tuberville’s seat or any other statewide office in Alabama, those in the state party may want to bug Saban about running until he files a restraining order. If they can’t press an altruistic case, they could note that at the very least, being Alabama’s senator can’t be more chaotic than being Alabama’s football coach. If Saban enjoyed beating Auburn coaches in his old industry, there’s one field out there in which he could try to do it again. This one carries more fundraising responsibilities than running the Crimson Tide, but only marginally.