Despite political pressure, US teachers lead complex history lessons on race and slavery

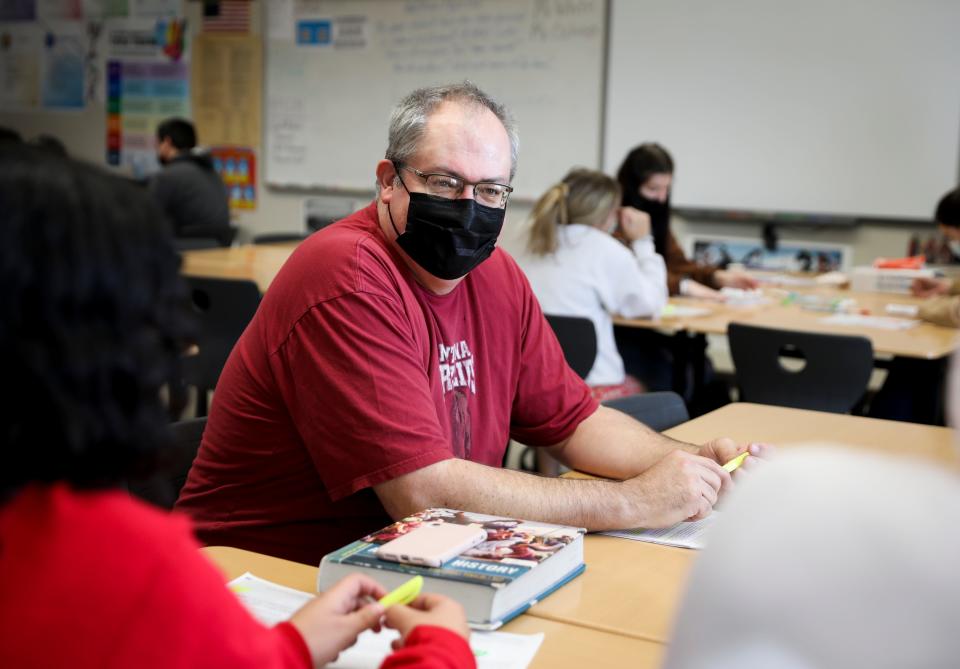

INDEPENDENCE, Ore. – History teacher Frank White starts every year by asking students to observe a painting of a tree above his desk.

"What color is the tree?" he asks.

Students on one side of the room always say green. Those on the other side say white.

They're both right – it's a holographic image. Before explaining, White goads the teenagers, asking them why their peers on the other side are lying.

The annual exercise sets the tone for White's history classes at Central High School, signaling different opinions aren't necessarily malicious or wrong. It lays the foundation for sensitive topics, such as race and identity, which White's advanced placement U.S. history class and traditional history classes address each year.

Such classes – and history teachers themselves – are under intense scrutiny as the country clashes over race, identity and culture and the specifics of how schools should teach those issues in American history.

Republicans in 42 states have moved to limit discussions about whether the United States has a racist history, along with the teaching of unconscious bias, white privilege and discrimination, according to a tally by Education Week magazine. Fourteen states approved bans or restrictions on how schools discuss racism or sexism.

'Walking a tightrope': Critical race theory bans heap additional stress on teachers

Critical race theory, which examines how racism permeates institutions, isn't traditionally taught in public schools, but the legacy of slavery is. Should teachers sanitize otherwise historically accurate lessons? Or defy the new orders? What do lessons on such topics even look like?

To answer that, USA TODAY Network reporters sought to observe middle and high school history classes this year during units on slavery, race and racism. We asked schools in big cities, small towns and dense suburbs – requests that were frequently denied.

In Ohio, Columbus Dispatch reporters reached out to 48 districts seeking advanced placement U.S. history curricula and an opportunity to shadow classes. Four sent back course syllabi; the others declined to participate or never responded.

In New York City, Education Department officials didn't answer repeated requests to shadow a willing teacher, eventually citing COVID-19 safety concerns. The department did allow USA TODAY to watch one class on slavery via Zoom.

Privately, some teachers said they feared reprisal from parents, school boards or local elected officials. When teachers said yes, reporters observed robust debates, critical thinking and texts from diverse sources – all features of high-quality lessons, according to education scholars and history teaching groups.

Students grappled with the ambition and reality of the Declaration of Independence. They discussed their own identity and politics. Lessons we observed did not include anything resembling indoctrination, the shaming of white students for the sins of their ancestors or talk of critical race theory.

Most history teachers strive to teach the values and tenets of living in a democratic society, said Maurice Blackmon, a social studies teacher at Essex Street Academy high school in New York City

"To grasp the full scope of that, you have to understand where you came from and how society got on its feet," he said. "It’s about looking at different aspects of what has sustained our country and the forces that have worked to uproot it."

Reviewing lessons in face of new law in Tennessee

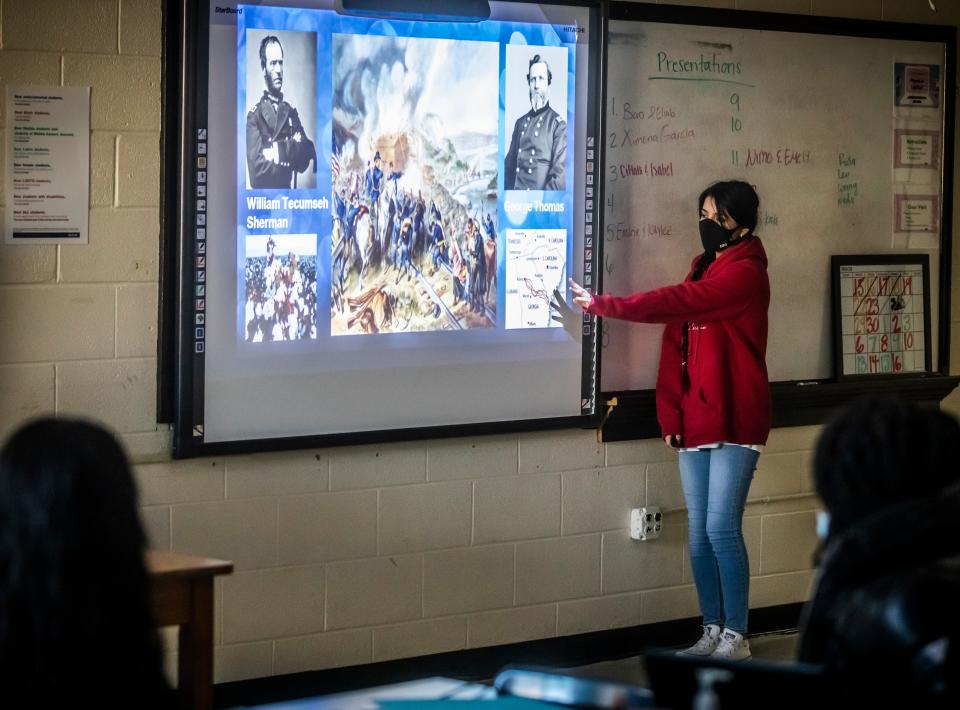

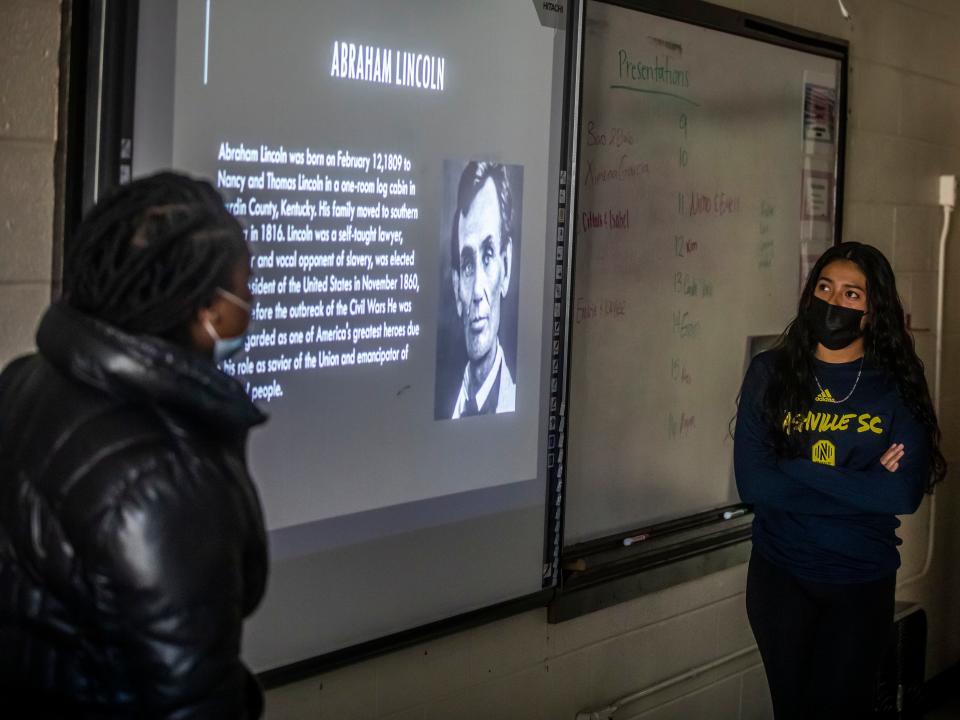

At Glencliff High School in southwest Nashville, students in AP U.S. history this fall could pick from a list of 16 Civil War topics to research and present. The list included famous battles, military movements and figures such as Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis – controversial in part because they both enslaved people and publicly espoused racist views.

No students chose Lee or Davis. Many worried that they couldn't neutrally present "all sides" of those men's lives or that they'd need to defend their actions, teacher Mary-Owen Holmes said. Part of that trepidation stems from a law passed by Tennessee's Republican-led Legislature last year, which prohibits public schools from teaching 14 concepts related to race, systemic racism and white privilege.

Lawmakers argued the law ensures students learn a complete history that presents both sides. They want to make sure that nobody feels what the law calls "discomfort or other psychological distress because of their race or sex" and that nobody is forced to "bear responsibility for past actions by other members of their race or sex."

Junior Emarie Hill said she didn't understand how teachers were supposed to present "both sides" of slavery.

"There aren’t two sides," she said. "At least not a positive and a negative."

Holmes aims to prod students toward a more nuanced understanding of people's thinking and actions at the time of the country's founding and early development. She rethought topics this year because of the law, she said.

"I try to say, 'Well, why do you think Jefferson Davis is bad? What evidence can you give me?’ and try to draw out some of their comments a little bit more," Holmes said. "And when they have shared a little bit, in the case of something like Jefferson Davis, I can say, ‘Well, historians typically would agree with you.’”

More than 60% of Glencliff's students are Latino, and many are new immigrants learning for the first time about the complex racial dynamics in state and national history. Many had not learned about the civil rights movement or Reconstruction.

The classroom doesn’t shy away from disagreements, said Nimo Hassen, a junior, who wears a hijab. This year, students heatedly discussed their views on a religious community in Oneida, New York, founded in 1848 on free love and polygamy.

“A lot of us have different backgrounds, so we don’t always agree on things, so it can be uncomfortable sometimes,” Hassen said.

Hill said most school curriculum is biased. Lessons on the Civil War rarely focus on the accomplishments of Black people, she said, and Hispanic and African American history and culture are discussed more in music class than social studies.

"We spend a lot of time looking at negative things instead of the positives,” Hill said. “It makes me uncomfortable” as a young, Black woman, she said. “We are more than just slavery.”

A lesson on slavery and the economy in New York

In New York state, Republican lawmakers introduced a bill last year that would ban critical race theory courses, as well as teaching that individuals should bear collective responsibility or guilt for the racial acts of their ancestors.

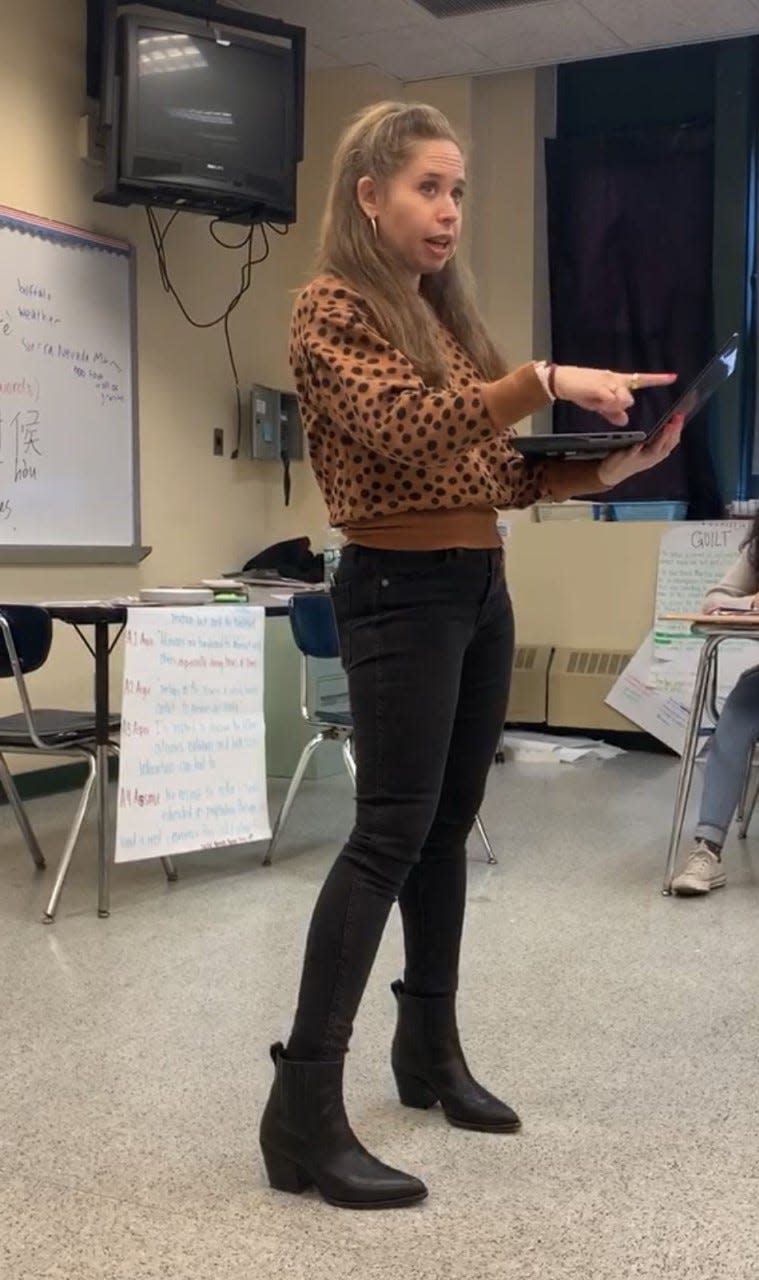

The bill, which is unlikely to become law, hasn't slowed longtime AP U.S. history teacher Sari Beth Rosenberg at the High School for Environmental Studies in Manhattan. She shapes her classes around student discussion and debate, featuring provocative questions about the interplay of race, economics and politics.

Rosenberg began one class on slavery and the Civil War in November by posing a question:

“If only 25% of Southerners owned enslaved people, why did many more people in the South defend and support it?”

Hands shot up.

"Because it was bringing in a lot of money for the economy," one girl said.

The discussion turned to the value of human labor at the time and to the psychological and social implications of slavery.

"When you have slave labor in America, it devalues paid labor," Rosenberg explained. "But that actually makes it more confusing, right? Why would someone who doesn’t have slave labor, and probably never will, take up arms to defend slavery, when it actually undermines the work they may be doing?"

There was a long pause. Then another girl spoke.

"Because they’re not on the bottom of society anymore," she said. "And they feel better because enslaved people are on the bottom."

A lawsuit over critical race theory at Democracy Prep

Though traditional public schools have denied accusations of teaching critical race theory, one charter school network unabashedly embraces a platform of anti-racism. Democracy Prep schools focus on preparing students for active citizenship; discussions about equity and race permeate many classes. After launching in New York City, the network enrolls more than 7,000 students in schools in five cities.

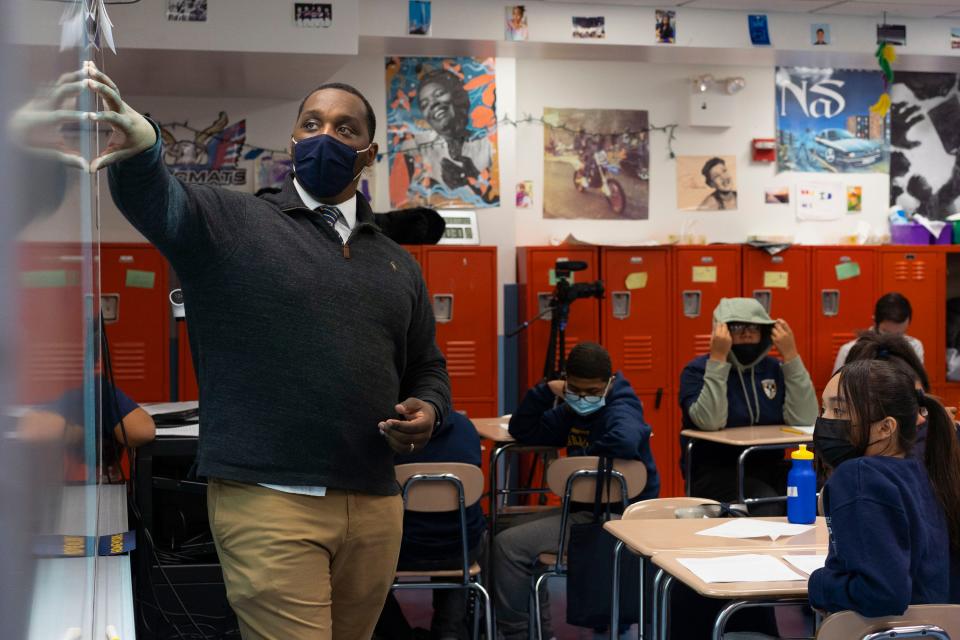

At Democracy Prep Harlem Middle School this fall, a lesson on the Revolutionary War challenged a class of seventh graders with two tough questions:

Should African Americans have sided with the British or the colonists? Was the Declaration of Independence a sign of progress or a contradiction?

“This isn’t about what Mr. Joyce thinks. This is about what you honestly feel,” teacher Joshua Joyce told the class.

Students debated, basing their arguments on facts and their analysis of texts and primary sources they'd studied.

Most students called the Declaration of Independence a contradiction. They split on whether African Americans should have sided with the British or the rebelling colonists.

The British promised enslaved people their freedom if they fought for England, and the loudest voices calling for a break from Britain were enslavers, students argued.

The British treated enslaved people poorly, too, others countered. The economic incentives of cash crops in the colonies fostered some of the poor conditions.

Joyce interjected only when a student needed to more fully support an assertion.

“I wanted students to take away the importance of looking at history from multiple perspectives,” Joyce said after class.

Ghazi Gibbs, 12, said he feels comfortable talking about challenging topics such as slavery because of the respectful and research-based forum his teacher created. Most of the students in class were Black or Latino.

"I feel like Black people should talk about it," said Gibbs, who is Black.

Democracy Prep is not immune to controversy. In late 2020, a Las Vegas parent sued the network on grounds that a class exercise on racism, identity and privilege violated her son's First Amendment rights when he refused to participate and was given a low grade.

The school defended its curriculum. The lawsuit is pending.

White privilege in a rural school in Oregon

At Central High School in Oregon, administrators said they haven't experienced pushback on how educators such as Frank White teach about race and identity.

Communities have different thresholds for tolerance. Less than an hour away, Newberg School District board members banned Black Lives Matter and gay pride signage in classrooms last year. A Newberg teacher came to school in blackface to protest vaccine mandates, and administrators learned of high school students running a mock "slave trade" on Snapchat that degraded classmates with racist and homophobic slurs.

Oregon lawmakers have not sought to restrict discussions of racism and slavery in schools, though one pending bill would require schools to publicly post all course curricula online.

At Central High School, all the teachers are white. Of the more than 1,000 students, almost half identify as Hispanic or Latino. That same ethnic breakdown is reflected in this year's A.P. U.S. history class.

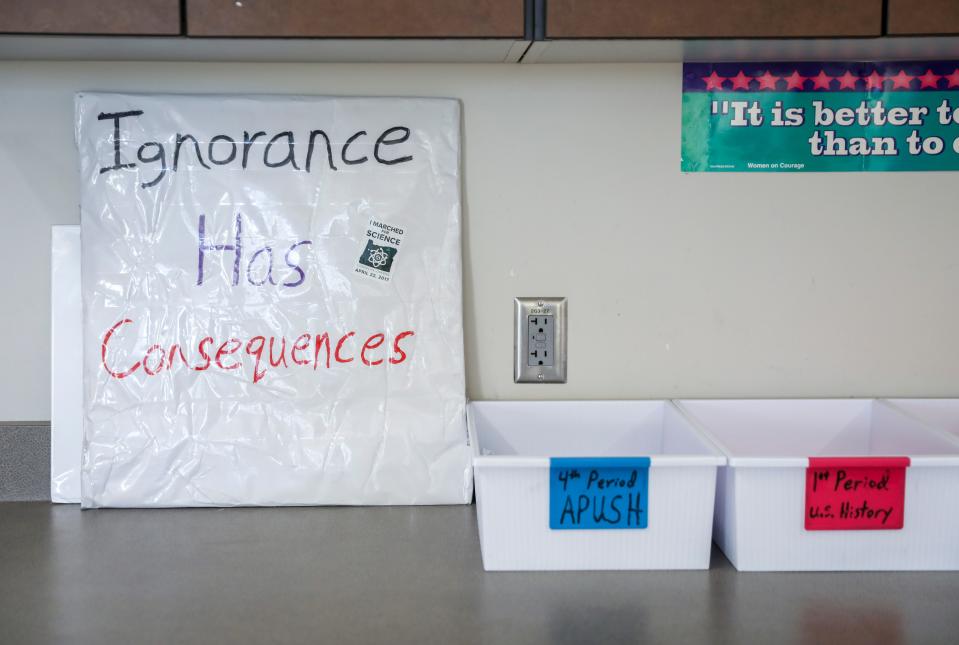

White, the history teacher, presses students to consider how people of different races and cultures experienced historical events. His classroom features a Mexican flag, a book about banned texts and quotes by feminist authors.

He wants students to think critically about what they learn, from the Vietnam War to the civil rights movement. He stresses Oregon's history, he said, including its vote on whether to join the Union as a free or slave state and its vote to exclude Black people from the state's 1857 constitution.

His lectures include jokes, and he narrates historical events like he's telling campfire stories. He encourages students to connect the past to the present.

"When any of us are held back, there are consequences for all of us," he tells them.

Connecting civil rights, Chicano movements to modern times

During a lesson on the civil rights movement this fall, White's students studied Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail" and an excerpt from Ta-Nehisi Coates' nonfiction book, "Between the World and Me."

In the discussion, Riley Young, a junior, recalled a sports fundraiser at school. Despite the school's diversity, nearly everyone at the fundraiser was white, he said.

Young hadn't noticed until someone pointed it out.

"Being white in this type of community is the privilege of not having to think about it," he said. Someone at the event who was not white might have felt out of place, he said.

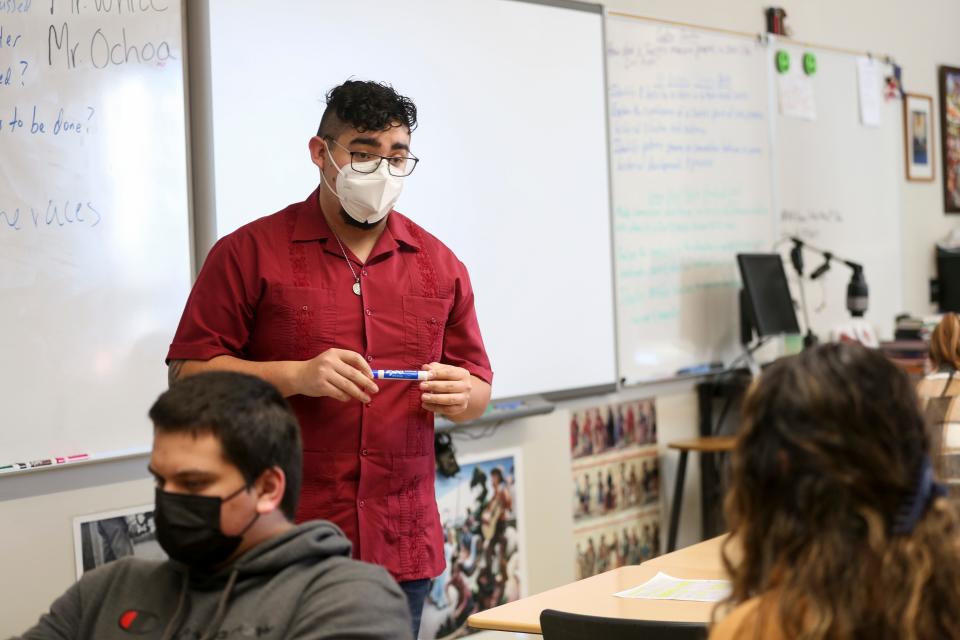

In January, Victor Ochoa, a former Central student training to become a teacher, taught a lesson about Chicano culture. He used a 1970 Los Angeles Times column by pioneering Latino journalist Ruben Salazar.

Ochoa was eager to return to his alma mater as a student-teacher. Growing up, he remembers learning about only one person who looked like him: labor leader Cesar Chavez.

The discussion prompted junior Bryanna Prado to reflect on her own identity.

"I've always labeled myself as a Latina," she said to the class. She realized she could explore what being Chicana means to her.

Understanding more than just "the white" part of U.S. history, she said later, makes her feel more welcome in class.

"Everyone in the U.S. is history," Prado said, recalling words from her teacher. Whatever your background, "you are U.S. history."

Contributing: Megan Henry and Sheridan Hendrix, The Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Critical race theory uproar: How history teachers design key lessons