What did Memphis kids think of the 2024 solar eclipse? We asked this MSCS science class

The third graders at Memphis-based Scenic Hills Elementary were ready for the solar eclipse.

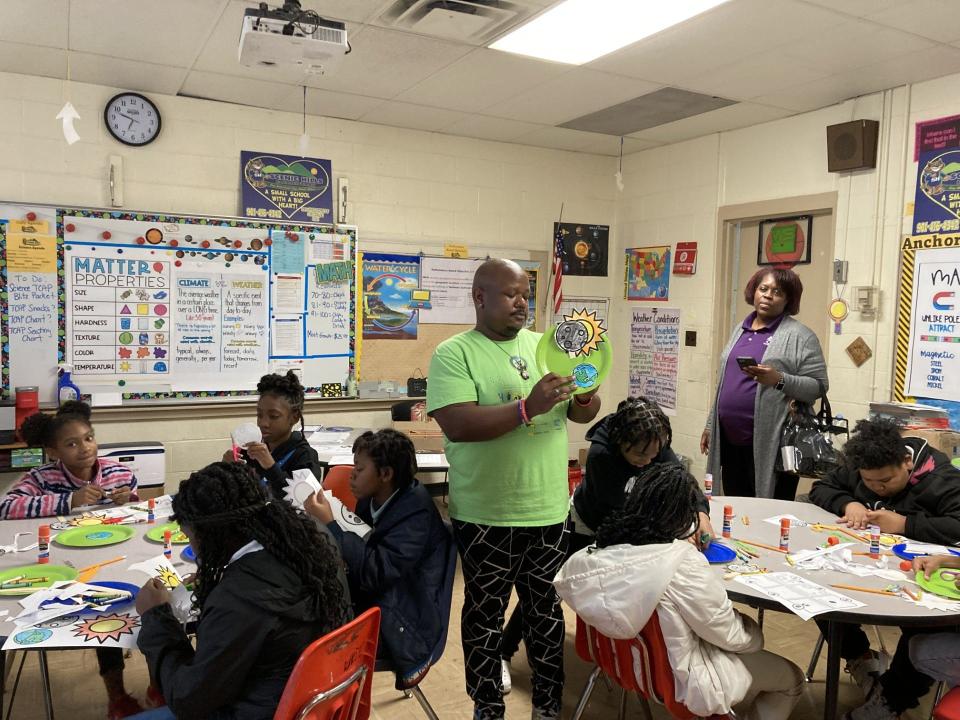

In the classroom of science teacher Kael Moore, around 11:30 a.m., his students were coloring moons, Earths, and suns, which they cut out of paper. The moons and suns were then glued to popsicle sticks and inserted into slits in a paper plate. The earths were also glued onto the plate, and the students were able to use the sticks to move the moons in front of the suns.

The art project was meant to help the students better understand the heralded solar eclipse that they would start to witness in the next hour. But even before then, most of them seemed to have a firm understanding of the science behind it.

Students knew it was caused by the moon passing in front of the sun. Several noted that though the sun was dramatically larger than the moon, the moon would still appear to cover it because it was so much closer to the Earth.

They knew the danger of looking at the eclipse without the specially designed glasses that had been provided for every student. The fear of going blind was real. One boy also made sure a Commercial Appeal reporter understood that, in Memphis, we wouldn’t see the moon completely block off the sun, only most of it.

Still, even though they had learned about the eclipse, few remembered seeing one. A total solar eclipse hadn’t passed through the country since 2017 when they were toddlers. And as they finished their art projects, they wondered just what it would be like.

One student spoke about the possibility of nocturnal animals waking up as the sky darkened. Birds, he said, could start singing. Bats might fly through the sky. Crickets could chirp. Another student entertained the possibility, however remote, that he might gain superpowers ― specifically superhuman strength and durability.

In any case, they were excited ― and so was their teacher.

“This is almost like a dream, to me, in a way, just to share this moment with them,” Moore said. “It’s a part of history, really. “We’re just looking to go outside, enjoy the sunshine, and witness the eclipse together.”

A bite out of a cookie

Just after 12:30, the students headed outside, spread blankets onto the ground, donned their glasses, and stared into the sky.

“I see it! I see it!” some cried.

Others laid out like they were sunbathing and gazed upward.

The moon was slowly starting to come into view, and it covered just a tiny part of the sun. Armani and Malik, two students in another third-grade class at Scenic Hills, looked at it keenly.

“It’s like somebody took a bite out of a cookie,” Armani observed.

This led to a host of other food-related eclipse descriptions from his nearby classmates:

“It’s like a little piece of pizza [was] cut off.”

“It’s like a circle ice cream sandwich that somebody took a bite out of.”

“It looks like someone took a bite out of something and just left it there.”

“It’s like a baby took a bite out of a honey bun.”

As time passed, some students’ interest in the eclipse waned. The sluggish moon didn’t seem to be in any particular hurry to cover up the sun, and many of the elementary schoolers weren’t going to monitor it continuously ― especially when they were outside on a gorgeous day.

“I’m trying to go hoop,” a boy told The CA.

“But what about the eclipse?”

He shrugged. “I’ve seen it already.”

Many started to run around and play. Teachers passed out popcorn, chips, and Kool-Aid. Still, the students didn’t forget the purpose of the afternoon, and they checked in on the progress of the moon intermittently.

A treasure chest

Around 1:30, with the moon covering much of the sun, Armani and Malik noted that it looked “like a banana.”

They were enjoying the afternoon; it had been their favorite experience of the school year thus far. They understood that this was a rare moment, and one they likely wouldn’t get to experience again for several decades.

Another solar eclipse of this magnitude isn't expected in the contiguous United States again until 2044 ― at which point Armani and Malik would be adults. By that point, Armani was hoping to professionally cut hair, and Malik wanted to feed the homeless.

Armani donned his glasses and looked back up at the sky. During the eclipse in 2017, when he was just a few years old, he had watched the astronomical event with his father, Floyd. But Floyd had since passed away, and Armani had been thinking of him as he watched the moon slowly come between the Earth and sun.

He intended to put his eclipse viewing glasses from the day in his “treasure chest,” where he kept mementos of his father.

How hot is the sun?

Once the moon covered nearly all the sun ― about 95% of it ― and the city grew slightly darker, the eclipse recaptured the attention of just about everyone it had lost.

Two boys who were running around by the playground glanced into the sky with their glasses, yelled “Oh my God,” and sprinted back to their classmates so they could view it with them. Armani, Malik, and several others wondered how hot the sun was ― at the surface, 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and at its center, it reached 27 million degrees Fahrenheit.

“Twenty-seven million degrees!” they cried.

The CA asked Armani, one more time, what the eclipse looked like, now that only a sliver of the sun was showing. He took a close look and returned to his “cookie analogy.” But this time, it didn’t just look like one bite had been taken out of a cookie.

“It looks like somebody bit it, bit it, bit it, and the ends right there,” he said, pointing upwards. “One more bite and it’s over.”

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: What MSCS students thought of 2024 solar eclipse in Memphis, Tennessee