Report says Chicago police violated civil rights for years

CHICAGO (AP) — The Justice Department on Friday laid bare years of civil rights violations by Chicago police, blasting the nation's second-largest department for using excessive force that included shooting at people who did not pose a threat and using stun guns on others only because they refused to follow commands.

The report was issued after a yearlong investigation sparked by the 2014 death of a black teenager who was shot 16 times by a white officer. The federal investigation looked broadly at policing and concluded that officers were not sufficiently trained or supported and that many who were accused of misconduct were rarely investigated or disciplined.

The findings come just a week before a change in administration that could reorder priorities at the Justice Department. Under President Barack Obama, the government has conducted 25 civil rights investigations of police departments, including those in Cleveland, Baltimore and Seattle. President-elect Donald Trump's position on the federal review process is unclear. His nominee for attorney general has expressed reservations about the system, especially the reliance on courts to bring about changes.

Asked about the investigation's future, outgoing Attorney General Loretta Lynch said talks between Chicago and the government would go on regardless "of who is at the top of the Justice Department."

The federal government's recommendations follow an especially bloody year on Chicago streets. The city logged 762 homicides in 2016, the highest tally in 20 years and more than the combined total of the two largest U.S. cities — New York and Los Angeles.

The Chicago department, with 12,000 officers, has long had a reputation for brutality, particularly in minority communities. The most notorious example was Jon Burge, commander of a detective unit on the South Side. Burge and his men beat, suffocated and used electric shock for decades starting in the 1970s to get black men to confess to crimes they did not commit.

Chicago officers endangered civilians, caused avoidable injuries and deaths and eroded community trust that is "the cornerstone of public safety," said Vanita Gupta, head of the Justice Department's civil rights division.

The investigation began in December 2015 after the release of dashcam video showing the fatal shooting of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, who was walking away from police holding a small folded knife. The video, which the city fought to keep secret, inspired large protests and cost the city's police commissioner his job.

Friday's report "confirms what civil rights lawyers have been saying for decades," said attorney Matt Topic, who helped lead the legal fight for the release of the McDonald footage. "It is momentous and pretty rewarding to see that finally confirmed by the U.S. government."

Investigators described a class for officers on the use of force that showed a video made 35 years ago — before key U.S. Supreme Court rulings that affected police practices nationwide. When instructors spoke further on the topic, several recruits did not appear to be paying attention and at least one was sleeping, the report said.

Justice Department agents who questioned Chicago officers found that only 1 out of 6 who were in training or who just completed the police academy "came close to properly articulating the legal standard for use of force," the report said.

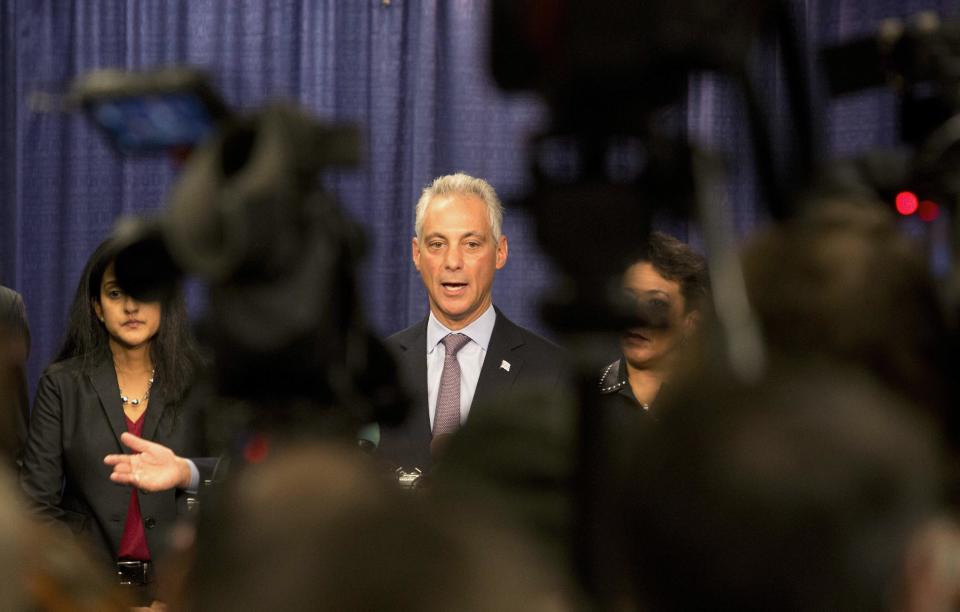

Mayor Rahm Emanuel said the results of the investigation were "sobering" and pledged to make changes beyond those already adopted. Federal authorities and city officials have signed an agreement that offers a broad outline for reform, including commitments to improved transparency, training and accountability for bad officers.

The report alluded to racial bias but did not center on it. A Department of Justice statement issued with the report said investigators "identified serious concerns about the prevalence of racially discriminatory conduct by some CPD officers and the degree to which that conduct is tolerated."

Black Lives Matter activists said they do not trust Emanuel to make real changes.

"I don't believe him any more than I believed him when he said that he never saw the Laquan McDonald video before the public saw it," said Arewa Karen Winters, who said she was the great-aunt of 16-year-old Pierre Loury, who was fatally shot by police last year.

Kofi Ademola said he was heartened by many of the government's conclusions. But with the Trump administration taking over, "we have no idea how this is going to play out."

Chicago has spent more than half a billion dollars to settle claims of police misconduct since 2004. But in half of those cases, police did not conduct disciplinary investigations, according to the federal report. Of 409 police shootings that happened over a five-year period, police found only two were unjustified.

The Justice Department criticized the city for failing to investigate anonymous complaints or those submitted without a supporting affidavit and for having a "pervasive cover-up culture."

Investigators said that witnesses and accused officers were frequently never interviewed, that evidence went uncollected and that witnesses were routinely coached by union lawyers.

"The procedures surrounding investigations allow for ample opportunity for collusion among officers and are devoid of any rules prohibiting such coordination," the report said.

Misconduct investigations are "glacially slow," with discipline often "unpredictable and ineffective," said Gupta, who described how police used stun guns on people for no other reason than they did not obey officers' verbal commands.

She also said officers do not get enough support to help them deal with the trauma of their jobs.

Trump's pick for attorney general, Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, expressed concerns at his confirmation hearing this week about the process favored under Obama that relies on intense scrutiny by federal courts. He said he was concerned that such legal action risks smearing entire police departments and harming officer morale.

The head of Chicago's police union said the Justice Department hurried the investigation to release its findings before Trump takes office. Fraternal Order of Police President Dean Angelo questioned whether the investigation was compromised because of its timing.

The mayor said Friday that the city has already made some of the recommended changes, citing de-escalation training and stricter use-of-force polices. Emanuel also addressed the Justice Department's concern that officers do not have nearly enough supervision. He pointed to his decision to increase the number of lieutenants and other supervisors.

The McDonald video showed officer Jason Van Dyke shooting the teen even after he slumped to the ground. Not until the video was released more than a year later was Van Dyke charged with murder. He has pleaded not guilty. Police reports suggested a possible cover-up by other officers who were at the scene.

___

This story has been corrected to show that McDonald was 17, not 18.

___

Associated Press writers Carla K. Johnson in Chicago and Eric Tucker in Washington contributed to this report.