Ecstasy-assisted psychotherapy is bringing peace to people with PTSD

Ed Thompson’s first experience with MDMA — better known by its street name, Ecstasy — was in an old house that had been converted into a peaceful therapist’s office with skylights. A far cry from the Dionysian abandon of a rave, the environment mimicked a comfortable living room, but for the cameras and microphones recording his session for a study that holds the promise of a treatment for the often-intractable condition known as post-traumatic stress disorder.

After swallowing a capsule of MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), Thompson lay down on a futon, put on an eye mask and felt a wave of empathy and forgiveness wash over him. He opened up to a psychoanalyst about traumatic experiences in his career as a firefighter that he had suppressed. Those topics had been simply too painful to broach before. Not anymore.

“I remember calling my wife and telling her — for the first time in years at that point — I had hope that I could be myself again. I had ‘re-witnessed’ the person I am, the person she married, and thought I might be able to come back. All hope wasn’t lost as we had expected at that point,” Thompson, 32, told Yahoo News.

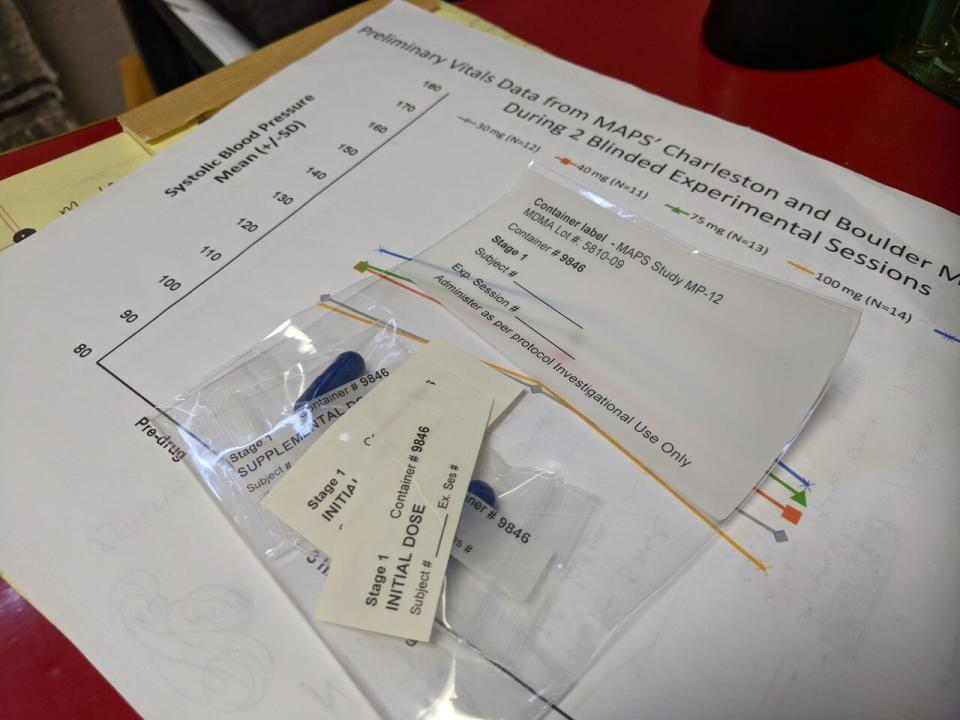

He was participating in a phase 2 clinical trial to see if MDMA-assisted psychotherapy could help military veterans, firefighters and police officers with severe PTSD. The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), a nonprofit based in Santa Cruz, Calif., sponsored the randomized double-blind pilot study for 26 patients with PTSD. Thompson said the process brought a sense of grace and understanding: “It was a world-opening experience.”

The participants were separated into two groups: one that received full MDMA doses and one that received “active-placebo” low doses. Both received 13.5 hours of non-drug psychotherapy and two day-long experimental sessions (totaling 16 hours) of MDMA-assisted therapy. The study found that 68 percent from the full-dose MDMA group did not qualify for a PTSD diagnosis one month after their second MDMA session, compared to only 29 percent in the low-dose group. The results were published in the peer-reviewed Lancet Psychiatry journal in May.

Brad Burge, a spokesman for MAPS, said the research nonprofit has also completed five other phase-2 clinical trials of comparable size. Most of the series’ 107 participants were women who survived sexual assault and abuse. The positive results appear consistent regardless of whether the PTSD stems from military service, childhood sexual assault, violent crimes or natural disasters.

“It’s not just the MDMA that’s doing this. It’s the MDMA plus psychotherapy,” Burge told Yahoo News. “A lot of the times, psychotherapy is especially difficult for people with PTSD because there’s been a terrifying event that feels like a threat to life. It may be a perceived threat or real threat. In the case of combat, it’s usually a real threat. That creates a lot of feelings of distrust, fear and paranoia. That causes people to shut down and not think about that difficult memory.”

Because of this barrier, psychotherapy might take months or years to start working for someone with PTSD — if it ever does. Every time a trauma comes up, someone might change the subject or walk out of the room. For these patients, psychotherapy without MDMA was tantamount to surgery without anesthesia — not just something unpleasant but something to be avoided at all costs.

Before receiving MDMA, Thompson could not discuss certain terrifying moments from his years as a firefighter in Charleston, S.C. He was able to compartmentalize the pain for a time but it finally caught up to him when nine of his peers died in a warehouse fire.

Compounding the trauma, Thompson’s twin daughters developed a medical issue that’s so rare there isn’t a name for it yet, in which their brains fired off signals that caused their breathing to stop. For about a year, each would turn blue and go limp in their parents’ arms about 15 times a day. Occasionally, they’d lose consciousness long enough to require emergency response — with Thompson sometimes driving the firetruck to his own house. (Both girls, now 5, are healthy today.)

“At the end of that, I was beginning to lose it. Everything started to pile up. I would sit at the fire station waiting for my address to come up again. I was a nervous wreck all the time. I was no longer functioning as I should,” Thompson said.

He started to numb his anxiety with alcohol and prescription drugs and almost killed himself accidentally about 10 times before his family intervened. He tried to go to talk therapy but nothing worked. He took administrative leave from the fire department. He wasn’t himself. He even left his wife while she was in labor to drink at a bar.

“I became a complete piece of trash as a human being. I may as well have been dead. I was losing my family,” said Thompson of this time in his life, which was dominated by nightmares, flashbacks and fits of rage. No matter where he was, Thompson had the combat veterans’ proverbial thousand-yard stare — a form of detachment to keep at bay an enveloping feeling of horror.

He tried to check into a psychiatric hospital but they wouldn’t admit him because, despite suicidal thoughts, he wasn’t actually trying to kill himself. While he was in the lobby, his therapist called and told him about a program through MAPS for combat veterans, firefighters and cops. There were only a few spots left in the study and she thought he would make a good candidate. Desperate, he jumped at the opportunity even though he didn’t have much faith things would get better. Dr. Michael Mithoefer, who led the trial, called Thompson on the phone to tell him more about the project.

MAPS assists scientists seeking funding and regulatory permission to study the potential of controlled substances for people with psychological disorders. In many ways, MAPS is continuing the work of clinicians from the mid-20th century who saw remarkable therapeutic potential for drugs like LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) and psilocybin, the psychoactive component in magic mushrooms. But when recreational drug use became part of a youth culture that frightened middle Americans, the resulting moral panic stigmatized research into this area for decades. Since its founding in 1986, MAPS has raised more than $47 million for research into psychedelic therapy and medical marijuana.

After a few sessions of preparation, Thompson had his first of three extensive medication-assisted therapy sessions on March 27, 2015, when he was 28. This was the first time he ever tried MDMA. As a firefighter since the age of 18, he was subject to random drug testing and steered clear of illegal substances.

The researchers had explained what kind of experience Thompson could expect and he had seen video of other participants’ sessions. But he was still apprehensive about confronting his painful experiences again.

He was surprised by how sober he felt throughout the process. He could access deeply suppressed memories and felt in control of his thoughts.

Mithoefer and co-therapist Annie Mithoefer, his wife, were artful in the way they guided the therapy. They didn’t pressure Thompson to talk about anything in particular and told him he didn’t need to delve into his painful memories. Then, within five minutes, he was talking about and processing previously harrowing memories. But it was painless.

“It was an intense experience but I was able to go into my most traumatic stuff without sending me a million miles away or into a panic,” he said. “This allowed me to process those emotions, have a little bit of reverence and understanding towards them, realize they were there, take them as they were.”

The other medicated sessions took place on April 24 and May 27. Afterward, Thompson and his wife worried that his newfound peace and confidence would fade, but it didn’t. It only got stronger, just as the therapists said it would.

“Within 24 hours, my eyes were opened and I was above water partially for a few minutes for the first time in a long time. The process continued to grow. By the end of my third session, my wife was celebrating. I was back to being myself.”

MDMA creates feelings of pleasure and emotional warmth by increasing the activities of three neurochemicals: dopamine, which reinforces behaviors in the reward system; norepinephrine, which raises blood pressure and heart rate; and serotonin, which fosters compassion and can help users recall memories they have suppressed. MDMA also increases hormones that occur naturally in the body, including oxytocin (“the cuddle hormone”) and prolactin, which are associated with bonding and intimacy. These same hormones are released post-orgasm and by lactating mothers.

These feelings of trust might not be safe for all environments, but they can be beneficial in the psychotherapeutic context.

“With MDMA, these feelings of connection and intimacy are really the opposite of PTSD,” Burge said. “In the context of therapy, you feel love and trust and that can help people open up more. Of course, those feelings are also reflected inward and they have more trust for themselves.”

The amygdala, an almond-shaped mass of gray matter commonly called the reptilian brain, which is associated with fear and anxiety, is hyperactivated in people with PTSD. When the amygdala is turned way up, otherwise mundane things that remind someone of their trauma can be terrifying.

“MDMA directly turns down the volume of the amygdala, even if you don’t have PTSD,” Burge said. “So scary things just aren’t as scary. In an uncontrolled setting, you might not want to get so close to the edge. But in a controlled setting, that’s great.”

The FDA granted MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD the designation of “breakthrough therapy” based on the results of phase two trials in August 2017. The change of administration in Washington did not affect the process.

“We don’t have any administration issues there. In fact, Trump’s hands-off policy towards the FDA and drug development seems to be helping us,” Burge said.

The phase three clinical trials are scheduled to begin in July with 200 to 300 participants at 16 locations in the United States, Canada and Israel. This is the last phase of research the FDA needs to evaluate before deciding whether to approve MDMA as a prescription drug. If the trials demonstrate effectiveness and acceptable safety levels, the FDA could approve MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for widespread use as early as 2021.

Support for this research isn’t coming exclusively from the political left. The Mercer Family Foundation, founded by the family of Robert Mercer, who played a major role in the Brexit campaign and funds right-wing projects in the United States, including Breitbart News and Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, donated $1 million to MAPS to help fund phase three trials enlisting military veterans.

“America’s veterans deserve the very best care,” his daughter Rebekah Mercer said in a statement at the time. “Current treatments for PTSD are helpful for many veterans but leave too many still suffering. MAPS is on the cutting edge of scientific research with their decades-long campaign to make MDMA-assisted psychotherapy a legal treatment for PTSD. We hope that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy will soon be widely available to veterans and millions of others suffering from PTSD.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ most extensive study on veteran suicide, which analyzed more than 55 million veteran records from 1979 to 2014, found that an average of 20 veterans killed themselves every day.

Ken Falke, a 21-year veteran of U.S. Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal, said the country’s current strategies for helping veterans with PTSD do not work and that mental health support needs to be destigmatized, especially for men. He said many therapists aren’t trained to understand the values and attitudes of military culture. He would like to see more efforts focused on helping veterans transition to civilian life. And he thinks there’s a place for medication, as long as it’s not a first resort.

“I think we need to research everything in the space,” Falke told Yahoo News. “There’s no organization in the world that does research as well as the VA, so why not at least research these things? But at the same time, let’s look at everything and not just more drugs.”

MDMA was first classified as a schedule one drug in 1985. This designation — which also covers heroin, LSD, cocaine and marijuana — indicates a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use. Critics of the war on drugs say this designation has more to do with politics than science.

From the early 1980s until the present, Burge said, the National Institute on Drug Abuse has sponsored tens of millions of dollars in studies on how harmful MDMA can be. MAPS was able to draw on all that research when it started its phase two trials around 2000 to show that MDMA is safe to administer in controlled settings, in moderate doses, for a limited number of times. In other words, research intended to demonstrate harm was used to show its relative safety.

The public is rightly suspicious of new drugs. Not only did pharmaceutical companies play a major role in driving the nation’s crippling opioid epidemic, but they routinely invent diseases to sell more drugs and broaden the diagnostic boundaries through a process called “disease mongering.” But the administration of MDMA for PTSD is much different than other drugs that have been foisted on veterans. Unlike antidepressants, for instance, patients will not need to take MDMA for the rest of their lives while dealing with side effects and lining Big Pharma’s pockets. MDMA is only administered two or three times for significant and lasting reductions in PTSD symptoms and only within the context of psychotherapy. At no point would patients take the MDMA home or pick up a bottle at the pharmacy.

One benefit of legalizing the consumption of MDMA in this context is that people interested in the drug’s therapeutic properties will know what they are getting. According to surveys, when people buy Ecstasy (sometimes called “Molly”) on the streets, the tablet might not contain much MDMA at all. The pills are often diluted with other substances like caffeine, ketamine or Adderall, that can mimic some of the effects of MDMA, such as an energy boost. Pure MDMA is less like amphetamines than what’s available on the streets. In the clinical trials, patients are given a comparable dose to what someone might take recreationally — between 80 mgs and 120 mgs.

It can be difficult to talk about drugs like MDMA honestly because the dual social phenomena of the psychedelic era and the war on drugs has left a lasting impact on the national psyche. Both had gaping blind spots. Many ’60s free spirits failed to appreciate just how dangerous certain substances could be and many ’80s conservatives failed to appreciate their potential when handled appropriately.

There are clear-cut examples of fear-mongering that have tarnished our understanding of MDMA, such as the debunked allegation that it creates holes in the brain, popularized on infamous episodes of “The Phil Donahue Show” and “The Oprah Winfrey Show.” They showed pictures from a late 1990s research study that showed holes in the brains of monkeys who received massive doses of MDMA. But the researchers accidentally used huge doses of methamphetamine instead of MDMA.

No one was surprised that massive doses of methamphetamine created holes in the brain. Though the scientists’ retraction was covered in the media, it didn’t get the same traction as the horrifying first report, and the misperception stuck.

According to MAPS, a pharmaceutical company would not be able to obtain exclusive rights to profit off MDMA because the patent has long since expired. If approved, MDMA would be taken only two or three times for a lasting solution to a condition that drug companies would prefer to treat with daily doses of medication for a lifetime.

There’s still a lot of misunderstanding around PTSD. Many people who have it don’t even realize they do or don’t feel “entitled” to have it. Domestic-violence victims might think that it only affects people who protect and serve. Cops might think it only affects soldiers. And soldiers might think it only affects special forces in intensive combat.

“You’re not going to tell someone with cancer that they’re a weak person because they got cancer,” Thompson said, “but people feel like when they have PTSD, it makes them weak, despite whatever happened or caused it.”

He hopes that sharing his story will help to destigmatize PTSD.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The inside story of Obama’s birth certificate and the birth of fake news

California’s Gavin Newsom wants to lead the way to a post-Bernie, post-Hillary party

The Eighth Circuit strategy: How abortion foes are lining up cases to challenge Roe

Photos: Rescue ship Aquarius docks in Valencia after a weeklong odyssey at sea