How election misinformation, conspiracies led to felony grand jury indictments in rural AZ

It only took five interviews to unanimously convince a grand jury in Arizona to indict two Cochise County officials on felony election interference charges, according to transcripts obtained by The Arizona Republic.

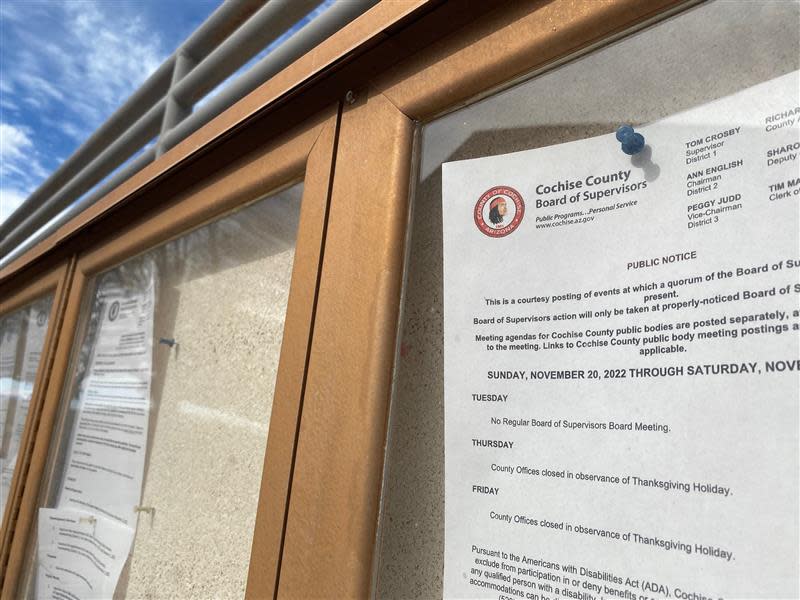

The grand jury proceedings, which lasted two days in Phoenix, ultimately resulted in the indictment of Supervisors Tom Crosby and Peggy Judd in November 2023.

Four witnesses — Crosby, Judd, Cochise County Attorney Brian McIntyre and Special Agent Bill Knuth with the Arizona Attorney General's Office, who appeared twice before the grand jury — testified on the series of events that unfolded leading up to and in the aftermath of the 2022 general election. Judd invoked her right to refuse to answer any questions beyond providing her name during her examination.

Crosby and Judd, both Republicans, voted to delay certification of the vote in 2022. They were quickly sued, including by then-Secretary of State Katie Hobbs. One lawsuit resulted in a court order to certify the result, which the supervisors ultimately convened to do, though Crosby didn't show up. They sent their canvass of election results to state officials on Dec. 1 — three days past the deadline enshrined in state statute.

The documents shed new light on how known election deniers pushed voting conspiracies in Cochise County and offer details of the infighting among government officials that followed.

The transcripts show holes in defense attorneys' arguments to remand the case or return it to a grand jury for a new indictment. And they reveal jurors considered indicting two others in the case — the county recorder and Bryan Blehm, an outside attorney who has previously represented Republican Kari Lake and partisan ballot audit contractor Cyber Ninjas.

Grand juries are tasked with assessing evidence presented by prosecutors to determine if there is probable cause to levy charges against an accused individual. Grand jury transcripts are typically not made public to protect jurors and witness testimony.

The Arizona Republic successfully intervened in the case to unseal the transcripts after Crosby and Judd challenged the grand jury proceedings leading to their indictment. They alleged grand jurors should have been better informed of applicable election laws and that state prosecutors didn’t properly inform jurors of Judd's right to refuse to answer questions.

The Republic's review of the documents found prosecutors read applicable laws to the grand jury numerous times and repeatedly allowed jurors to ask questions. Prosecutors also informed jurors that Crosby and Judd had the right to refuse to answer questions.

Brian Gifford, an attorney representing Crosby, said grand jurors weren't reminded of a law related to state of mind in criminal offenses.

"The law on state of mind was read once to the grand jury, three months prior to any deliberation related to Mr. Crosby," Gifford said, adding that the reading of the statutes was lengthy. "There is no way the grand jury remembered or absorbed the law on state of mind that was read that day."

An attorney for Judd did not immediately respond to The Republic's request for comment on the transcripts.

Crosby and Judd both pleaded not guilty to the charges levied by the grand jury during a December court appearance. They've also filed motions to dismiss the case. A trial is currently scheduled for August, but attorneys said last month that date is likely to move to September because of scheduling conflicts.

How conspiracies took root in Cochise County

In the weeks leading up to Election Day, Crosby was approached by a group of people who convinced him the county's tabulators weren't properly certified.None of the six men — Paul Rice, Michael Shafer, Daniel Wood, Brian Stein, Daniel LaChance and Hoang Quan — had experience or professional credentials in conducting elections.

However, several were known election deniers. Rice, Steiner and Wood had previously petitioned the Arizona Supreme Court to declare 20 elected officials were “alleged usurpers” who were “in office illegally," and to rule that voting systems statewide were “contractually uncertified and illegal," according to court filings.

Crosby told jurors that he considered Rice "a friend" and had met him "well prior" to the 2022 election. He was familiar with Rice's thoughts on voting and ballot counting — in fact, their friendship developed through "mutual interest in elections integrity."

When Rice presented him with a 200-page document that falsely explained that the county's tabulators weren't properly accredited, Crosby trusted him.

About a week before the election, State Elections Director Kori Lorick sent county officials an email warning them of "a conspiracy" regarding "the federal lab testing accreditation process." Her message included documentation from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission showing Cochise County's tabulators remained certified for use.

Crosby wasn't convinced. He told jurors he considered Rice and the others who approached him to be "experts" even though they lacked credentials because "any citizen in here can become an expert on any subject they want, and it doesn't require that anybody have a degree in anything."

"I believed Paul Rice et al. and not Kori Lorick," he told jurors. "Just because Kori Lorick says that such and such is true, does that mean it's true?"

The hand count

With two weeks to go until Election Day, the Cochise County Board of Supervisors met in Bisbee to consider a hand count of ballots.

Two versions of the plan were up for consideration. One agenda item called for a full hand count of all ballots cast in the election. The other instructed Cochise County Recorder David Stevens to perform a hand count audit of all of the county's voting precincts.

Over the course of four hours, dozens of citizens voiced conspiracies of improperly certified tabulators and a stolen 2020 presidential race. Rice and others in his group were among the public speakers.

McIntyre, the county attorney, repeatedly told supervisors hand counting was unlawful. Lorick called into the meeting and told supervisors she would sue if they pursued an expanded hand count. And a spokesperson from the Arizona Counties Insurance Pool warned supervisors that it would not cover any legal costs resulting from the matter.

Crosby and Judd ultimately voted to authorize a hand count audit of voting precincts, over objections from Democratic Supervisor Ann English.

Judd said at the meeting that any legal advice was unlikely to change her mind.

“I'd like to take this chance. My heart and my work has been in it and I don’t want to back down. I might go to jail,” she said about the proposal.

Crosby told jurors he believed that plan was legally sound, despite advice to the contrary. He pointed to an informal opinion from Deputy Solicitor General Michael Catlett stating a hand count audit of all precincts could be permissible as long as the review was limited to five contested statewide and federal races appearing on the ballot.

Catlett left the Attorney General's Office after Democrat Kris Mayes won the election as the state's top prosecutor in 2022. He now sits as a judge on the Arizona Court of Appeals.

His opinion was authored days after the Cochise County meeting on hand counting. McIntyre quickly sent Catlett a response asserting the opinion contained fatal legal errors, and asking Catlett to revoke it until it went through the full vetting process.

"I am particularly concerned with the failure to analyze the issue under well settled principles of statutory interpretation," McIntyre wrote. "As noted by my civil deputy, the opinion eviscerates the hand count audit process provided for in Arizona law."

Trial court judges blocked the hand count on Nov. 7, 2022. That decision was ultimately affirmed by the state appeals court last year.

But Stevens still made preparations to press on with the effort in the days after the election. He said at the time that he was moving ahead on the advice of Blehm, his attorney. Both men were aware of the court order.

“I have to drive on as if it’s going to happen," Stevens said.

Grand jury transcripts show jurors also considered charging Blehm and Stevens for those actions.

"Why aren't Mr. Stevens and Mr. Blehm party to this?" one juror asked lead prosecutor Todd Lawson right before indictment deliberations. "Based on the evidence we've seen, they should be."

Lawson replied that the draft indictment prepared by his office was "a suggestion" and that jurors could decide "who is to be charged."

"It is a draft," he said. "You're free to reject it, amend it however you see fit, or you can adopt it as written."

Stevens and Blehm did not respond to The Republic's request for comment for this story.

A debate or a trial?

Meanwhile, supervisors mulled certifying results.

They first convened to certify the election on Nov. 18, 2022 — a little more than a week before the Nov. 28 statutory deadline. An hourslong meeting ensued.

Rice, Wood and Steiner again spoke on concerns about the certification of the county's tabulators. Lorick also addressed the board. She repeated that a hand count was illegal and the vote tallying machines were sound.

But Crosby and Judd said they wanted more information. The two voted to delay certifying election results until the deadline.

When the day came, the two again voted to delay. A court would later order the county to certify its results. Judd and English did so at a Dec. 1 meeting that Crosby did not attend.

Crosby told jurors he wanted Rice and other election deniers to "debate" Lorick. He attempted to have the group respond to information presented at the Nov. 18 meeting by Lorick. His efforts were stymied by English, who was running the meeting as chair of the board.

Later, he said English "misagendized" the election certification item, which again prevented debate on whether the county's tabulators were properly accredited. He told jurors he missed the Dec. 1 meeting on the advice of his attorney, and speculated if Judd had also done so, it would have triggered "an instant U.S. Supreme Court case."

"Was that your intent from the beginning," a grand juror asked.

"Oh, no," Crosby replied.

McIntyre told jurors that the type of discussion Crosby wanted on the issue was "not the kind of meeting that exists."

"What they discussed was essentially wanting to have — for lack of a better word — a trial over who was right. Was the secretary of state right or were these three main individuals right about issues with certification," McIntyre said.

Asked if such a "trial" was lawful and part of standard procedure, McIntyre demurred: "They have no authority to do so."

Infighting amid the chaos

Two days after the election, McIntyre wrote a letter to dozens of attorneys representing parties in the court case that challenged the hand count.

It came as Stevens prepared to conduct the count of the county's ballots without regard to the court's decision.

"This office has become aware of the potential that certain actors may attempt to go forward with an 'expanded hand count,'" McIntyre wrote. "I write out of concern as the public prosecutor of Cochise County of the potential criminal acts that would be inherent in proceeding."

He listed five state laws he believed would be violated if Stevens attempted a hand count.

"I have alerted the appropriate authorities to the potential violations based upon the statements of two elected officials connected to this," McIntyre concluded. "It is my sincere hope that no action will be required of them and that the rule of law will prevail."

McIntyre told jurors the letter was intended to send a warning: He would pursue criminal charges if anyone tried to touch the ballots under Cochise County Election Director Lisa Marra's care.

"I was really worried that someone was just going to try to walk into the Elections Department or gain access in some way and remove ballots," he said.

But Crosby called the letter "threatening" and said it ultimately limited his options for legal representation. He said he later tried to obtain counsel from several of the attorneys listed on the missive but was unsuccessful.

"These guys, you know, basically (were) trying to deny me representation, which I didn't appreciate worth a hoot," he told Lawson before the grand jury. "And I still don't."

Days later, he and Judd sued Marra and asked a judge to order her to hand over the ballots so Stevens could conduct his hand count. They quickly withdrew the lawsuit.

"No all day court which is great because I've lost so many days dealing with this during a major election," Marra tweeted out. "Fact remains elected officials filed a personal lawsuit against a tenured local Gov't employee with an impeccable record. Not just in official capacity, sued me personally."

Months later, Marra would resign from her position, citing a hostile work environment. She won a $130,000 settlement payout from the county related to the claims.

McIntyre: 'There never appeared to be any intent to follow the law'

A year after the election, as Crosby sat before the grand jury, there were some questions he still wasn't willing to answer.

"Do you recall filing a lawsuit or causing a lawsuit to be filed by counsel against Ms. Marra and the county," Lawson asked Crosby.

"I think I will take my Fifth Amendment privilege on that one," Crosby replied. This was one of seven times over the course of the multi-hour interview when he cited his constitutional protection against self-incrimination in declining to answer a question from Lawson.

Judd also invoked Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights to decline to answer seven questions, which made up the entirety of Lawson's examination other than when he asked for her name.

McIntyre told jurors that Rice, Wood and Steiner had fully convinced Crosby and Judd "that a hand count was the only legitimate means of conducting an election."

He suggested the two were certain they were doing "the right thing" — even though "the right thing was to follow the law."

"There never appeared to be any intent to follow the law if the law didn't mean we get to do a hand count," McIntyre said. "That became the focus."

Sasha Hupka covers county government and election administration for The Arizona Republic. Reach her at [email protected]. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter: @SashaHupka. Follow her on Instagram or Threads: @sashahupkasnaps.

Reach reporter Stacey Barchenger at [email protected] or 480-416-5669.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Grand jury transcripts: Charges considered against Kari Lake attorney