The Meltdown in Michigan Says It All About Where MAGA Is Headed

At 2 p.m. in the basement of the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, the mood was distrustful, the air was humid with human moistness, and the disagreements over minor procedural issues simply would not end.

The people assembled in this particular conference room were delegates from Michigan’s 9th Congressional District. They were among those who had come to Grand Rapids this past March for a statewide meeting to help nominate a Republican presidential candidate. And despite all of them believing that the nominee in question should be “Donald J. Trump”—as they insisted on saying his name, for some reason—they had already been there for four hours.

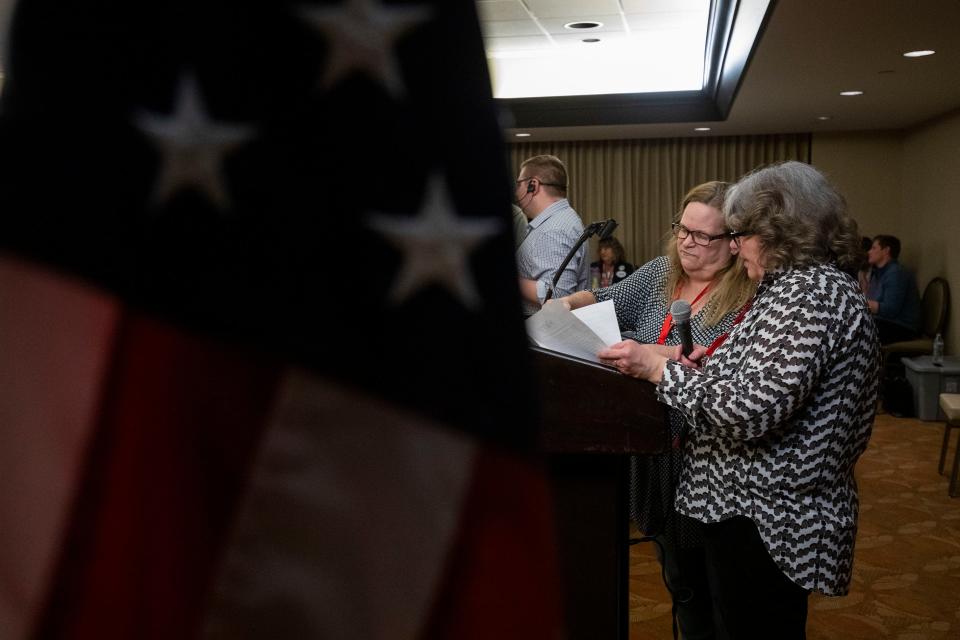

One of the major points of contention was which of these delegates would get to attend the Republican National Convention later this year in Milwaukee to take on the largely symbolic act of officially certifying Trump’s victory in the primary. And things took a particularly sour turn when the meeting chair, Deb Ross, said that a delegate named Billy Putman, who was seeking to represent the district, may have submitted paperwork identifying himself as “uncommitted”—rather than as a supporter of Trump’s.

Putman is a bearded man whose suit jacket and evident enjoyment of public speaking marked him as the room’s most likely aspirant to higher office. (He lives with his parents, his siblings, and their families in a single home, an arrangement which was featured in a 2017 TLC reality series called Meet the Putmans.) He and others considered the allegation that he might not be a Trump supporter to be slanderous. In turn, he accused Ross of being “bogus,” and “disenfranchising everyone in this room.”

Though Ross soon corrected the record, damage had been done. One delegate said with disgust that Ross had lost her credibility by entering “fraudulent” information into the discussion. Others raised dark suspicions that a different group of potential national delegates may have falsified their credentials. A woman in a pink shirt and a man with a blond goatee stood and shouted “point of order” and “point of privilege” repeatedly. (They didn’t seem sure which was appropriate.)

Finally, a man in a turquoise button-down shirt rose with the focused intensity of a military officer preparing to issue an order of great significance. “Motion to vacate the chair!” he yelled. This was as serious as things could get, and not incidentally, a reenactment of the mutiny that far-right Republicans in Congress led against House Speaker Kevin McCarthy last October.

Ross did not respond directly. “The parliamentarians have both advised that we move on, and that’s what we’re doing,” she said. But others called for a referendum on the motion to vacate, and soon there was too much shouting going on for Ross to do anything else.

This scene was a small expression of the absurd dysfunction that has characterized the operations of the Michigan GOP for nearly a year. It is also a window into the problems of the current Republican Party writ large—one of many intraparty conflicts at the state and local level that are exploding across the country.

The problem, in short, is that the MAGA activists in charge are eating each other alive. States in which old-guard “establishment” Republicans were run off—seemingly paving the way for unified efforts on behalf of Trump—are instead beset by resignations, lawsuits, and financial crises. Conflicts are ongoing in Nevada, Idaho, Arizona, and Georgia as well as Michigan, and are tearing apart smaller chapters at even more local levels.

It’s a perplexing state of affairs given that these Republicans are so united behind their presumptive nominee. But as I learned in Grand Rapids, Donald Trump’s wishes are sometimes beside the point to the people who followed him into the party. Their loyalties are to causes bigger—and stranger—than electing one person to the presidency.

Michigan’s March convention was a sort of culmination of MAGA infighting in the state.

In 2020, Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump here by a 150,000-vote margin. Trump’s supporters said the victory had been achieved via fraud centered in the largely Black city of Detroit. Subsequent lawsuits, hearings, and investigations failed to substantiate any allegations of election theft, but the chaos did end up elevating the loudest, most excitable voices to the top of the state’s Republican Party. When their leadership turned out to be unusually dysfunctional and bankruptcy-adjacent even by Trump-era standards, the state organization splintered into two rival factions.

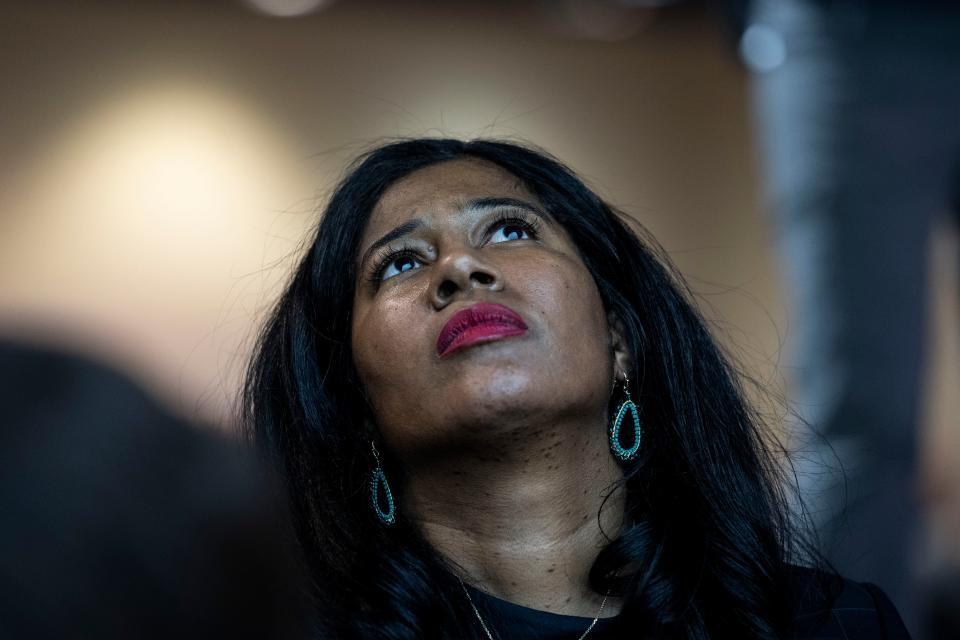

One faction was run by Kristina Karamo, who, before the fall of 2020, had been a community-college professor and single mom who occasionally volunteered for local Republican causes and hosted a small-time, conspiracy-minded Christian podcast. On election night, she joined a number of other Trump supporters to observe vote-counting at an events complex in Detroit. Karamo filed an “incident report” alleging that she’d seen malfeasance there, including the suspicious delivery of ballots between 3 and 3:30 a.m. After it became clear that Biden was going to be declared the winner, her report was cited in lawsuits seeking to have the results thrown out.

Those efforts went nowhere legally, but Karamo proved to be a popular advocate of the cause, appearing on Sean Hannity and Lou Dobbs’ Fox shows and, in 2021, traveling to Arizona to observe a so-called audit of election results. Later that year, although she denied believing in QAnon conspiracies per se, she spoke at a QAnon conference in Las Vegas. She became popular with activists across the state who fit an ascendant “grassroots” ethos—culturally blue-collar MAGA voters who believed that the 2020 election had been stolen.

In April 2022, Karamo won a nominating-convention vote to become the party’s candidate for secretary of state—the role that, in Michigan, actually administers elections. Angela Hall, an Upper Peninsula county chair and Karamo supporter, remembers being impressed by her presence. “She gave a speech that was just unbelievable. She’s a very powerful orator. And I said, ‘Well, she’s got something here,’ ” Hall told me.

Karamo lost that race by 13 points, but it didn’t slow her political momentum. Naturally, she didn’t concede defeat; in 2023, she told the news site MLive that the election system is not trustworthy enough for her to be able to say with confidence whether she won or lost. In February 2023, she was elected state party chair—replacing Ron Weiser, a real estate millionaire and University of Michigan trustee. (Talk about establishment!)

Karamo’s critics say she immediately went about putting the state GOP on a “path to bankruptcy.” She failed to raise money and spent what money there was on things like having Passion of the Christ and Sound of Freedom star Jim Caviezel give a keynote address at the party’s annual conference in Mackinac Island. (It cost $110,000.) She got into a legal dispute with Comerica Bank over a defaulted $500,000 line of credit; the bank said in legal filings that trying to understand the party’s position on the matter was “like trying to nail Jell-O to a tree.” Hall argued Karamo never got a fair shake: “As soon as she was elected, people were trying to get her out of her seat.” (Slate’s attempts to reach Karamo for comment were unsuccessful.)

As state chair, Karamo had taken over a party that was about $400,000 in debt; a subsequent critical report prepared by a former supporter of hers attests that this is not an unusual circumstance for a political organization coming off an election cycle, and says a debt of that size for a state party typically doesn’t take long to retire. But Karamo also wanted to shift the party’s emphasis away from multimillionaire donors enmeshed in elite political and business circles. One major donor told the Associated Press that Karamo’s administration actively rejected his offer to speak with her about giving money. Alas, in the first six months of her tenure, her fundraising strategy only generated $186,000 of the $8 million she had projected.

As 2023 drew to a close, Karamo had alienated many of her former allies and removed some of them from their subcommittee appointments after they began complaining about the financial problems. There were two physical altercations at party events; in one, a county chair named Mark DeYoung was allegedly kicked in the groin by an activist with a criminal history who was upset that a private meeting was taking place. (“He kicked me in my balls as soon as I opened the door,” DeYoung told reporters. The ball-kicker, James Chapman, claimed DeYoung swung at him and added that DeYoung should have been prepared for retaliation when Chapman removed his glasses. “When you see me taking my glasses off, I’m ready to rock,” he said. Chapman has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial.)

There was no one, really, to act as the adult in the room. “Trumpers had been gaining clout in the state party beginning in 2016, as measured by precinct delegates,” a self-described “classic” Republican named Michael Schostak explained to me in February. “By 2022 they had become the largest bloc of delegates, thus electing their preferred candidates. That made the rest of us feel unwelcome and led us to withdraw from the state party.”

Then this year, on Jan. 6—yes, Jan. 6—Karamo’s critics on the state committee held a meeting just outside of Detroit. Karamo’s supporters boycotted, which allowed the anti-Karamo faction to establish a quorum and vote her out. A few weeks later, with Trump’s approval, they voted to replace her with Peter Hoekstra, a bald Dutch American who has the glowing, confident face and well-fitting clothes of someone who is often on TV. (A failed candidate for governor and the Senate, he served as Trump’s ambassador to the Netherlands.)

Karamo responded by denying the “allegations” that she had been removed and saying the “rogue faction” that had replaced her would be “dealt with swiftly.” She refused to give Hoekstra control of the state party’s bank accounts, such as they were, or its communications logins and website, MIGop.org. So Hoekstra and his supporters set up a rival site, MI-Gop.org, booked the Grand Plaza in Grand Rapids for the March 2 convention, and filed a lawsuit seeking to compel Karamo to yield control of the party.

On Feb. 14, the Republican National Committee issued a ruling that Karamo had been properly removed—but Karamo ignored this as well, sending blast emails which said that Hoekstra had been selected by “globalists” and the Council on Foreign Relations in order to cover up evidence that Joe Biden was going to steal the 2024 election. She urged delegates to attend a rival convention she would hold in Detroit, where it all began.

The factions fought over who was rightfully in charge, and a number of county chairs told me by email they intended to support Karamo by taking their whole delegations to Detroit instead of Grand Rapids. (Several of them referred to Hoekstra as “Peter Hoaxtra.”) On Feb. 27, though, the judge issued a preliminary injunction holding that Hoekstra’s claims were likely to prevail at trial and ordering Karamo to stand down. When a related motion was rejected, the Karamo faction finally conceded control of the party, although not without issuing announcements about having been “disenfranchised.”

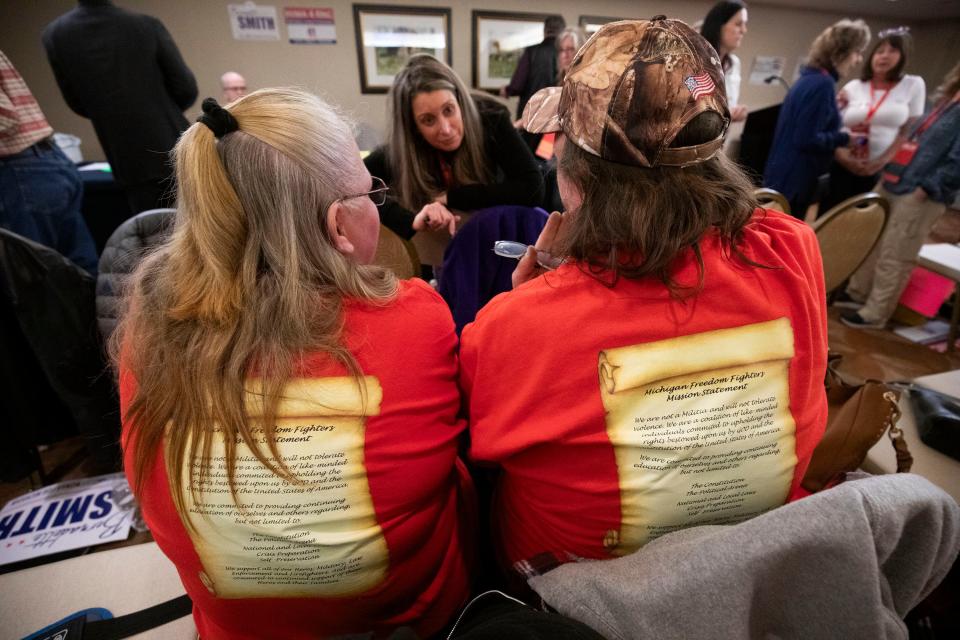

Some Karamo loyalists still boycotted the convention after the Hoekstra regime ruled that some two dozen counties had failed to file the proper paperwork and wouldn’t be “credentialed” in Grand Rapids. (They met instead in Houghton Lake, a resort area in the center of the state known for pontoon boating.) Others went to the Grand Plaza Hotel for the big showdown.

For all the buildup, the mood in the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel was, for the most part, convivial. Tables were spread out on an expansive second-floor balcony, and the area was already packed and buzzing at 7:55 a.m., five minutes before registration officially opened.

Still, it was only mostly convivial. Hoekstra, now the fully established leader of the Michigan GOP, had started the day doing an interview with the Fox Business channel, whose camera was set up in the first-floor hotel lobby. When he arrived at the top of the staircase near the registration tables, he was immediately confronted by a man in a red T-shirt whose level of agitation and disregard for Hoekstra’s personal space could only be described as alarming.

After a brief exchange, Hoekstra moved away. The man who confronted him, a bearded, middle-aged delegate from the Detroit suburb of Novi, was shaking with anger. “I asked him how he paid for this, because he doesn’t have control of the bank account,” he said, a Karamo-coded accusation which implied shadowy interference by deep-pocketed conspirators.

In the 9th District’s basement meeting room, Deb Ross opened the meeting by apologizing sarcastically for the tight quarters: “I guarantee you in Detroit there were enough seats for everybody.” This seemed to confirm what I had heard, which is that District 9—a heavily red congressional district that covers far-north Detroit suburbs and a number of counties in the rural “Thumb” area—was going to be the best place to see “fireworks.” In addition to Ross’ evident loathing of the Hoekstra regime, there were two uncredentialed pro-Karamo county delegations within the district’s boundaries that had decided not to go Houghton Lake, and had arrived instead in Grand Rapids in hopes of being seated by assent of the other delegates.

In the back of the room, I met Scott McMahan, a self-funded MAGA citizen journalist who had anticipated the conflict and was livestreaming and narrating disputes as they took place. He was a friendly, well-built guy—there was evident dad strength in his shoulders—who told me that he had left a career as a realtor to start his outlet, Bigger Truth Media. During the day, a number of delegates recognized him and thanked him for his work.

It was odd that the 9th District was so tense, because it was clear that everyone present actually agreed that the two county delegations in question should be credentialed. But McMahan explained that several of the individuals conducting the meeting—including Ross—had held leadership positions with Karamo or were otherwise close to her. (Karamo’s press secretary, Lori Skibo, was seated in the front of the room.) During this time, they had, in the view of others in the district, run it like a club, speeding through their agendas in order to rubber-stamp whatever it was Karamo wanted. (Ross did not respond to a request for comment.)

The day’s meeting, under the auspices of the new Hoekstra team, was a chance for those who’d felt railroaded—like Billy Putman—to air their grievances. The Hoekstra regime had made a calculated decision to support the seating of the renegade counties’ delegations in a gesture of magnanimity, but that didn’t preclude arguing about how to do so properly and whose fault it was that it hadn’t been done already. Within six minutes—you can see it on McMahan’s video here—someone wielding a large binder stood to tell Ross that she wasn’t correctly following the bylaws governing the conduct of the meeting.

Ross announced that there had been a motion to end discussion of the issue, which Putman didn’t like. “There’s four other people in here that rose their hands to discuss,” he said. “Discussion is discussion until it’s ended!” Ross took a vote on whether to close the matter down. Her side (the “ayes,” i.e., those who wanted to cut off discussion) quite obviously lost—only for her to declare that “the ayes have it,” upon which the room exploded in incredulity. (This is at 9:40 in McMahan’s video—it’s a funny moment.) She retreated, asking the ayes and noes to stand on separate sides of the room. She then acknowledged that the noes were more numerous. As the discussion continued, tension dissipated.

Elsewhere in the hotel, “presidential preference” votes and the selection of delegates to the national convention from other districts were duly taking place, also with an undercurrent of paranoia. In one room, a delegate who was voting “present” on every subject told me that he was making a statement about the convention’s illegitimacy. Rob Steele, who was running for reelection to the Republican National Committee and was nominally the most establishment figure present, gave a stump speech in which he touted the support he had helped provide to MyPillow founder Mike Lindell, a prolific loser of election-related lawsuits, “in his election integrity work.” A life-size standup poster advertised a long-shot Senate candidate named Sandy Pensler, whose campaign slogan was “Let’s take our country back from the morons.”

In the 5th District, a national convention delegate candidate named Jon Smith used his speaking time to say he regretted that some of his relationships with others in the room had been recently strained. He was wearing a backward baseball cap and spoke to me about how he thought the Republican Party could use online messaging to better compete with Democrats for new voters. He also said he didn’t think the unity-convention “Kumbaya stuff” was going to last. He has some experience with intraparty drama: According to a 2023 Reuters article, Smith led a faction that “deployed armed guards to bar moderate delegates from a county meeting” in Hillsdale County in August 2022. That was after the moderate delegates had been expelled from the organization over accusations that they had infiltrated the party in the 1970s to promote socialism.

Back in the 9th District, once Ross stepped aside and let her critics take the microphone to make the case for deposing her, they lost steam. The man in the turquoise shirt accused her of “disrespecting the rule of law” and running the room like “a fricking dictatorship,” but others came forward and said replacing her would be too drastic. A woman wearing a shirt that said “CHEMTRAILS ARE KILLING US” drew applause for saying, sensibly, that selecting a new chair would be a waste of time. Even Putman rose to support the effort to keep things civil a short time later, although he was met with widespread groaning when he transitioned into what sounded like a campaign speech about securing the border and cutting off funding to Ukraine.

It still took some time afterward to finish all the day’s votes. There was a long debate over whether a potential delegate who didn’t think Donald Trump was necessarily conservative enough should be removed from eligibility, or whether it was OK for her to simply go unelected. There was also a break for a fundraising pitch by a speaker who mentioned during her talk that she was, “unfortunately,” a (fake) Trump elector who was facing “quite a few criminal charges.” After six-plus hours of deliberation, the district wrapped things up around 4 p.m.

It was a temporary suspension of hostilities, not a long-term settlement of differences. Impassioned paranoia is inherent to the MAGA political style, and without any establishment Republicans or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention experts around to fear and loathe, the MAGAs in Michigan have no one to accuse but each other.

McMahan helps illustrate this point. For all his affability, he holds some dark beliefs. In fact, his contention is that Karamo is a tool of powerful puppet masters who are engaged in a long-running scheme—one which may have been engineered by the American intelligence community—to infiltrate and destroy the Republican Party. On his site, he calls the effort a “covert brainwashing operation,” describing “a plan that appears to have begun in 2017 or even earlier to raise up a previously unknown Christian conservative” and “make her into a powerful political figure who would ignite the imaginations of the conservative grassroots.”

The goal, McMahan writes, is to create “an ideological dictatorship at war with itself while deliberately bankrupting the party and embroiling it in legal troubles.” He sees evidence of this in the conflicts that have riven other state parties as well.

One might think that it doesn’t take a CIA-trained mastermind to introduce recursive loyalty purges, financial problems, and legal feuds into an organization led by Donald Trump. But McMahan and his readers don’t see it that way. When I texted McMahan to ask if he ever wondered whether Trump was himself to blame for the party’s paranoid and conflict-riven state, he called me immediately to say he had in fact thought about it “at length.” In the end, he said, he’d concluded that figures like right-wing media provocateur Steve Bannon—who may be in Trump’s orbit but tend to pursue their own agendas—were more responsible for the chaos. This is not an entirely far-fetched claim; as the investigative publication ProPublica noted in a September 2021 piece, Bannon launched a concerted effort through his podcast in 2021 to convince MAGA listeners that they needed to engage in a disruptive, confrontational purge of the party, down to the precinct level, of anyone who was not part of their movement. ProPublica did not, however, go as far as McMahan did in suggesting that this may ultimately have been done at the behest of Chinese Communist Party officials influencing Bannon via one of his business associates, the Chinese national Guo Wengui.

“I don’t know who and I don’t know what,” said Stephanie Hamilton, a short, spirited 9th District delegate who was friendly with McMahan at the convention. “But there’s something they’re trying to distract us from.”

Grand Rapids is home to Gerald Ford’s presidential museum, which is—under the circumstances, ironically—one big tribute to being genial. The descriptors printed on the wall in large letters in the museum’s majestic central rotunda include “BI-PARTISAN,” “TEAM PLAYER,” and “RESPECTFUL.” An exhibit defends Ford’s decision to preemptively pardon Richard Nixon, praising it as a compromise that allowed the country to move past a divisive era of acrimony.

Putting oneself in the mindset of someone who believes that Kristina Karamo is a sleeper agent whose mission is the destruction of a 170-year-old political party makes it easier to understand why these Republicans are having trouble moving past their own era of acrimony. On his website, McMahan accuses Karamo’s supporters of using “Alinsky tactics”—a reference to the mid-20th-century community organizer Saul Alinsky, who is often described in right-wing media as a godfather of leftist string-pulling and character assassination. But as he notes with annoyance, Karamo’s supporters also accuse Hoekstra’s supporters of using Alinsky tactics. This is not a political style built for compromise and coalition-building. Gerald Ford, after all, is dead.

Michelle Smith, another old-guard Michigan GOP veteran, has a simple theory about what’s going on: Trump’s sudden rise and surprising 2016 victory attracted a new cohort of activists who had not previously been politically engaged and did not, on some level, understand that it is possible to lose an election. “I’ve suffered losses before,” Smith told me on the morning of the convention. “A loss is a loss. But they say, ‘I got off my couch—why didn’t we win?’ ”

Angela Hall, the Karamo supporter and party chair who represents a county in the furthest reaches of the Upper Peninsula, tells a story about her entry into politics that mirrors Karamo’s—and lines up with Smith’s theory.

While she was a casual Trump supporter during his first term, Hall explained when I spoke to her by phone after she attended the alternate March meeting of non-credentialed counties, 2020 is when things really got going. “After the 2020 election, things just seemed off. The results didn’t mesh,” she said. “And then the Michigan Senate and House Oversight Committees held hearings where they interviewed election workers. I think each meeting lasted like seven hours. I watched every minute of both meetings, and I was devastated by what was said, under oath, as sworn testimony, as far as lack of election integrity, and just thought, well, I better start digging in, if I want to try and make a difference.”

Hall spoke to her state senator, a prominent conservative named Ed McBroom, at a meeting he held to explain his conclusion that the 2020 presidential election had been conducted fairly. She was part of a group of constituents that wasn’t satisfied. “We kind of started to go to more meetings,” she said.

Her concerns about election fraud overlapped with her feelings of being imposed upon by mask mandates and vaccination requirements during the pandemic. (She’s a dentist and, incidentally, a beekeeping enthusiast who plays the accordion.) “My life was being upended by government actions, and I was not happy with it. So that’s what got me involved. And then it just kind of went from there. I became part of the county party. And then I was elected to the state committee,” she said.

I asked Hall if she didn’t think there was something a little counterproductive or unusual about putting so much energy, in a presidential election year, into a conflict with a state leader that the presidential nominee helped put in place. She reminded me that she got involved in politics because of election integrity, mask mandates, and the loss of medical freedom, not because of Trump. He’s often described as the leader of a cult of personality. But for some modern Republicans, he appears to be more like a symbol of tribal affinity—a symbol of a deeper allegiance to conspiratorial beliefs, or to beliefs about having been treated unfairly by the rest of society. (The number of new Michigan Republicans who have criminal convictions or fraud accusations in their pasts—for the record, Angela Hall does not have any!—is striking.) “I’m very wary of putting my hope and trust in one person,” McMahan told me. “But I also see that he’s the only candidate that we have right now that could become president. I don’t like that there’s only one person, though—I would love it if we had some backup.”

Many new Republicans also got their start in the party basically by interrupting meetings—whether election-audit hearings, school board sessions, or COVID Zooms. Now, as the ones who are supposed to be running the show for organizations that basically exist to hold meetings, that can be a problem. They also make simple mistakes like funding the infamous Mackinac Island Jim Caviezel conference as a campaign event, which limited the maximum amount that any individual donor could pay to help defray costs. (If it had been sponsored as an administrative event, it could have been financed with unlimited donations.)

As the 9th District was wrapping up its business in Grand Rapids, I had asked Lori Skibo, Karamo’s press secretary, if she thought the day had gone well. She had the slightly wide-eyed but amused look of someone who will tell you that they have a lot going on.

“As long as all the ballots were counted, in a fair and transparent process, that’s all we’ve been worried about,” she said with a slight smile. “So yes.”

A few weeks later, Angela Hall forwarded me a flyer for a rally to be held outside the former party headquarters in Lansing. It called on the people of Michigan to “Stand in Solidarity” with the 24 counties that had been “disenfranchised” by the “hoax” state convention Skibo and I had attended.

Skibo was listed as a featured speaker. “The Grassroots,” the flyer said, “will be heard.”