'Farm Aid' 2020: Warren, Sanders propose rescue plans for family farmers

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

By nearly any metric, life for the American family farmer has become increasingly difficult if not impossible over recent years.

Farm bankruptcies are soaring, up 30 percent in six Midwestern states in 2018, according to Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The First Midwest Bank in Chicago reported in March that past-due agricultural loans were up by 287 percent year over year. Overall, farm income has dropped about 50 percent since 2013.

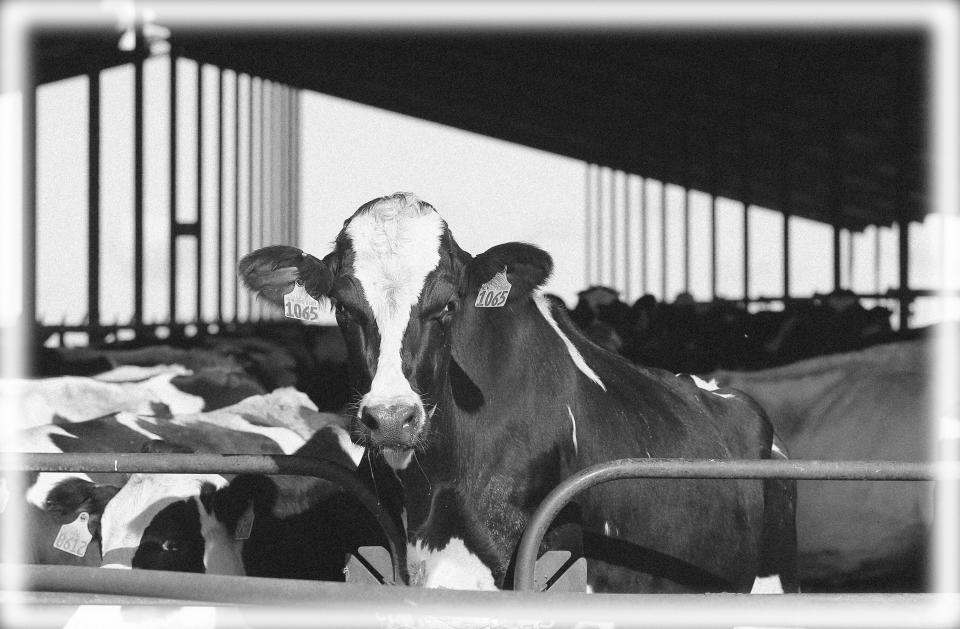

Since 2003, the number of dairy herds in Wisconsin has been reduced by half. Milk prices are down 40 percent over the last five years as an increase in corporate farms and more efficient milking practices have flooded the market. Making matters worse are tariffs on American dairy products, responses to President Trump’s trade war that have made international sales more difficult. Last year, a Massachusetts dairy co-op included information on a suicide hotline with payment checks to farmers.

There has also been a rise in consolidation of the industry, as large corporate farms have taken over more and more of the market. A 2015 USDA study found that 51 percent of U.S. farm production value came from farms with at least $1 million in sales, up from 31 percent in 1991, with adjustments for price changes. That same study found that farms comprising at least 2,000 acres accounted for 36 percent of all cropland, compared to just 15 percent in 1987. Large companies have been able to push much of the risk in agriculture to smaller farms through contract farming, maintaining control of the market and keeping the majority of profits for themselves.

“When you get to a place in a sector of the economy where 40 to 50 percent of that business volume is represented by four or fewer players, you have by definition what most economists would say is a noncompetitive [market], or at least a market that is less competitive than it ought to be,” said Roger Johnson, president of the National Farmers Union, which represents family farms.

Additionally, national security concerns have been raised about foreign companies buying American farmland, including China buying the largest pork producer in the U.S. in 2013. There is also new global competition from the expansion of farming in other markets, including South America, and a consolidations of the seed and chemical market via a series of recent mergers objected to by farming groups.

In the early 1900s, the government leaned on two key pieces of legislation to help loosen monopoly in agriculture, a series of antitrust laws and the 1921 Packers and Stockyards Act, which helped hold meatpacking companies accountable to ranchers and farmers. Over the ensuing decades, enforcement waned, culminating in the Reagan administration’s position not to pursue antitrust violations unless consumer prices were affected.

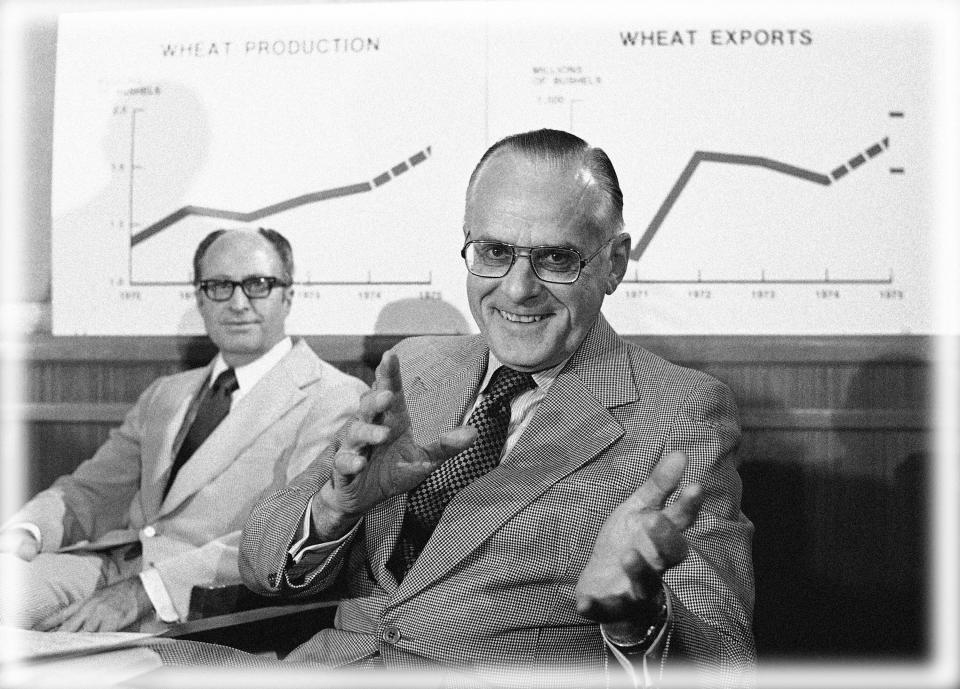

Corporate farms started gaining steam under President Richard Nixon, when Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz urged farmers to “get big or get out.” A 1979 pamphlet from the League of Rural Voters attributed the loss of family farms to “carefully developed and successfully implemented policies to eliminate family farmers,” suggesting the use of antitrust laws against Big Agriculture.

The combination of interest rate hikes, an increase in production, cratering prices and President Jimmy Carter’s Soviet grain embargo resulted in a rural crisis in the early 1980s. Despite millions raised by Farm Aid to rescue family farmers, within a few years the damage was done and the makeup of rural America had changed irrevocably, with just 2.2 million farms remaining in the mid-1980s, down from 6.8 million 50 years earlier.

In past campaigns, Democrats have discussed leveling the playing field between smaller farms and big ag. In 2008, Barack Obama released a plan to “strengthen anti-monopoly laws; change federal agriculture policy to strengthen producer protection from fraud, abuse, and market manipulation; and make sure that farm programs are helping family farmers, as opposed to large, vertically integrated corporate agribusiness.”

The pitch helped Obama win the Iowa caucuses and jump start the campaign that would give him the nomination and eventually the White House. Members of his Cabinet, including Attorney General Eric Holder and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, toured the country, hearing concerns of farmers, including some who risked alienating the sole buyer in their region by speaking out about the power of big agribusiness. But after the tea party wave in the 2010 midterms, the Obama White House essentially abandoned the issue until 2015, when a viral segment from comedian John Oliver’s “Last Week Tonight” exposed the hardships facing chicken farmers and helped pressure Congress into action.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren was the first major candidate to roll out an expansive plan to help the nation’s family farmers, in a series of proposals in late March. Warren’s plan would begin by targeting big ag, investigating some of the major mergers across the agriculture sector and using antitrust law to break up vertically integrated companies that control every step in the processing and distribution of food products. Such a move would require updating 35-year-old policies on vertical mergers, but Warren maintains this would open markets to smaller family farms.

The senator’s proposal would also include a national right-to-repair law, requiring farm equipment manufacturers to provide the necessary tools and information for owners to repair their own machinery, avoiding the expense and lost time of using authorized dealers. Warren’s plan would also rely on executive power over trade to require mandatory country-of-origin labeling on pork and beef, which would affect agreements with Mexico, Canada and the World Trade Organization. Her platform also calls for limits on foreign ownership of American farmland or agriculture companies, similar to a law already in place in Iowa.

Sen. Bernie Sanders followed in early May, launching his “Revitalizing Rural America” proposal during a campaign visit to Iowa. Much of Sanders’s proposal echoes that of Warren, including an increase in the trustbusting of big agribusinesses, right-to-repair, the enforcement of country of origin labeling and stronger oversight of foreign land acquisition. He called for bankruptcy relief for family farmers and more stringent enforcement of Clean Air and Clean Water laws against pollution from agribusiness.

Sanders also proposes reforming patent laws under which farmers have been sued for growing crops from proprietary seeds. He wants to strengthen rules on organic growing and labeling that are threatened by the Trump administration. The Sanders plan also called for enacting New Deal-style programs to regulate supply and demand of agricultural commodities and national grain and feed reserves that could be tapped in case of crop failures.

He also addressed trade. “Our trade policies should not hurt farmers and ranchers in America and across the world,” said Sanders in a speech earlier this month. “We need trade policies that prioritize domestic food security — not dumping low-cost commodities on other nations — undermining the local farmers there. Farmers, workers and environmentalists need a seat at the table during international trade negotiations.”

The Sanders proposal also includes policies beyond farming to help rural communities as a whole, including increased investment in rural education and health care. It would expand access to high-speed broadband and provide help to community banks and credit unions in rural areas.

Other candidates have also laid out plans to help rural communities. Former Rep. John Delaney has put forth a “Heartland Fair Deal” plan that would create incentives for people to move to rural areas and promote government contracts for businesses in those communities. Delaney told Yahoo News he would look to rejoin the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal and pass new antitrust legislation targeting big agribusinesses. In late March, Sen. Amy Klobuchar put forth an infrastructure plan that would expand broadband with the goal of having it in every U.S. household by 2022.

Mandates or subsidies for corn-based ethanol, which were major issues in previous election cycles, were not addressed in either the Warren or Sanders plan.

Trump has been friendly toward corporate farming in his time in office, with Modern Farmer calling his campaign’s agricultural advisers a “who’s who of industrial agriculture advocates” whose priorities would be to support “feedlots over farmer markets.” Since taking office, Trump’s appointees have rolled back a number of regulations intended to support smaller farms and ranches against large agribusinesses. Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, said he had “violent opposition” to those policies.

Iowa’s prominent role in the primary process means Democrats have an incentive to court farmers. These policies could also be helpful in winning over rural voters in swing states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. But despite predictions that tariff and trade war fallout would hurt Trump’s standing with farmers, multiple polls in recent months have shown the president still garnering healthy support from the agricultural community.

And there’s also a downside to siding with family farmers. Warren has already seen pushback against her plan from the big ag companies she’s targeting. The meat-packing industry spent millions of dollars lobbying against Obama administration regulations under the GIPSA (Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyard Administration) Act, delaying the rollout for years.

Vilsack, the former Obama agriculture secretary and Iowa governor who now works for a group representing corporate dairy interests, recently warned Democrats against going after big agribusinesses.

“There are a substantial number of people hired and employed by those businesses here in Iowa,” Vilsack said on the “Iowa Starting Line” podcast last month. “So you’re essentially saying to all of those folks, You might be out of a job. That’s not to me a winning message.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: