‘It feels sacred.’ Preserving these Charlotte church cemeteries protects Black history too

Wayne Johnson is a man full of stories. The Grier Heights native heard them from his elders, who got them from their elders, the farmers and masons who originally called the neighborhood home in the late 1800s.

Long story short, 70-year-old Johnson knows some things.

He also knows it’s his duty to continue sharing those stories and make sure they’re told right. Like the history of St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church and the pair of cemeteries where 250 people and their stories of freedom and perseverance lie buried.

Johnson said many of his ancestors lie buried in both historic cemeteries. One is in SouthPark near Sharon and Colony roads. The other is in Grier Heights off Wendover and Marvin roads.

So when a new development began crawling closer to the cemetery in Grier Heights in 2021, Johnson said it was time to protect the land in a more official way.

The St. Lloyd Presbyterian Cemetery Foundation was created in 2023. It’s a nonprofit with the goal of caring for both cemeteries, preserving the land and spreading the history to natives and newcomers.

“You’re new to my story, but this is the most important thing I’ve ever done,” Johnson said. “It’s the greatest thing that God has empowered me to do…Those cemeteries are going to be preserved. They can’t be removed. They can’t be demolished. Nothing.”

These 9 still-standing landmarks help keep Charlotte’s Black history alive

The lifespan of a Charlotte church

While the foundation was started last year, the development story goes back to 2004. The congregation’s story goes back further, to 1867.

Let’s start at the creation.

After the Civil War, Black people began to separate themselves from white control, especially through houses of worship. The first all-Black Presbytery in the U.S. was Catawba Presbytery, created in Charlotte in 1866, according to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission.

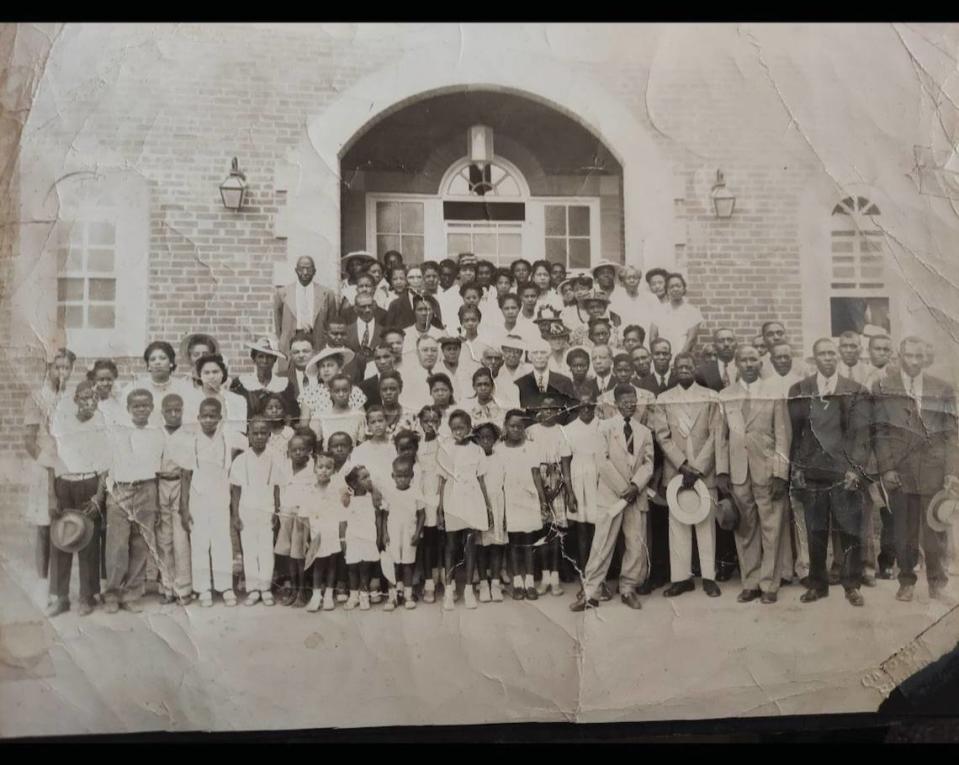

In October 1867, Black members of the Sharon Presbyterian Church in Sharon Township (now called SouthPark) sought to build a church of their own.

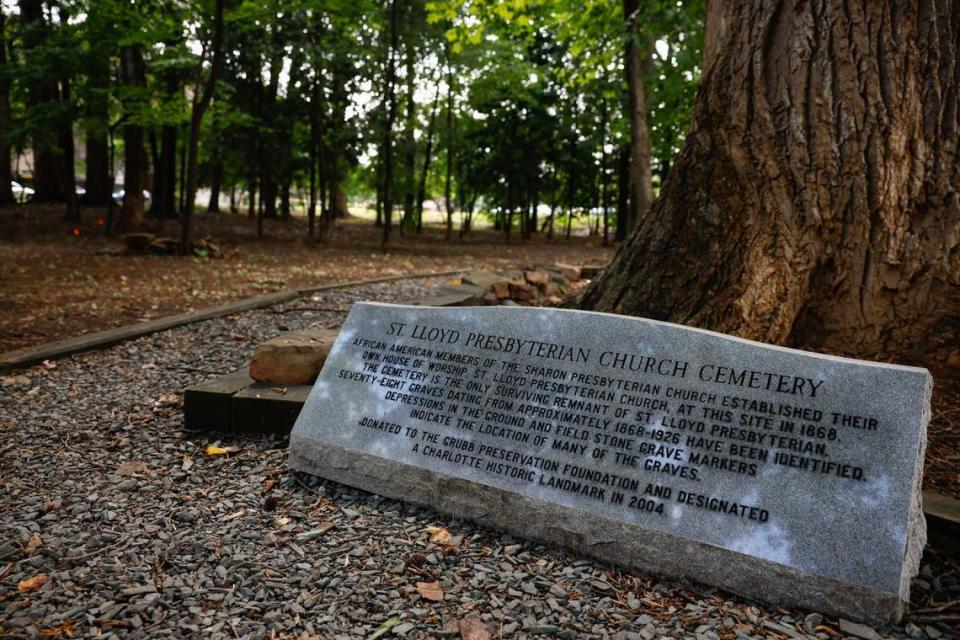

With the help of Catawba Presbytery, the group chose a spot on Sharon and Colony roads to build their church. On February 18, 1868, a deed was signed, an acre was purchased for $25 and the parcel became the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church and accompanying burial ground.

“It is clear that in the half-century following the Civil War, St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church was central to life in Sharon Township,” according to the landmarks commission. “In this rural area it provided spiritual guidance, acted as a social outlet for African Americans and provided a forum for developing Black leadership.

“It also served, in a time characterized by racial animosity, as a place of refuge, comfort, and encouragement for African Americans.”

Johnson echoed the sentiment. He said SouthPark is where things got started for Black people in southern Mecklenburg County. They laid the foundation for what SouthPark is today by being seamstresses, tending farmland and literally building the area up as bricklayers.

But in the late 1920s, the congregation was pushed out due to growing racial terrorism. The land was sold to former North Carolina governor Cameron Morrison, a white supremacist.

Johnson likened the move to what we would call gentrification today. Jim Crow laws, he said, pushed out Black people in a more physically violent way then today’s redlining or cost of living hikes.

“When they wanted to get you out of the neighborhood, they just burned you out,” Johnson said. “You had to leave because you couldn’t deal with the pressure they put on you.”

The SouthPark church was burned down, Johnson said.

But it was rebuilt in 1926 when the congregation moved to Grier Heights, a Black neighborhood founded around 1892 by Sam Billings, a formerly enslaved man.

That’s the church Johnson attended as a child, along with the rest of his family. As things go, the congregation eventually dispersed to other places of worship and the church closed in 1966.

But both cemeteries remained.

Development in the 21st century

In 2004, Clay Grubb, CEO of Grubb Properties, purchased several parcels in SouthPark with the intention of building a mixed-use development. When he learned of the cemetery, he went to work on his own preservation efforts.

He started a nonprofit called the Grubb Preservation Foundation and applied for a landmark designation. That was approved in 2005.

Fast forward to 2022, when Johnson said he learned of another development encroaching on the historic cemeteries. This one was in Grier Heights.

![“We used to swing on these [vines] when we were little,” says Wayne Johnson, Vice President of the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Cemetery Foundation. “This is going to be part of the art in our cemetery,” Johnson continues when talking about plans to keep vines in place during the renovation of one of St. Lloyd Presbyterian’s cemeteries in the Grier Heights neighborhood in Charlotte on Monday, July 8, 2024.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/xQpR7ubYD0bFN5YoWRt7AA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYzNw--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/charlotte_observer_mcclatchy_513/608639b0cebaf7162b9cced009ffc699)

DreamKey Partners had begun working on a 70-unit affordable housing complex. In 2022, it was in the process of securing funding and hosting neighborhood meetings about the development.

Fred Dodson, DreamKey’s chief operating officer and executive vice president, said through the meetings Johnson and the community made it clear that they didn’t want the development to impede on the cemetery. They voiced their desire to restore the cemetery and honor the people buried there.

Out of those meetings, Johnson and other community members started the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church Cemetery Restoration project. They held several clean-up events and began gathering funding to go toward their efforts.

Soon after, Johnson approached Grubb and said he wanted to combine the preservation efforts of the two cemeteries. Grubb agreed and helped create the nonprofit that exists today, the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Cemetery Foundation

Not leaving anyone behind

Johnson is vice president of the preservation foundation. One of its goals is to restore all of the headstones and acknowledge everyone who is laid to rest at the sites.

Ground Penetrating Radar studies performed at both sites show that there are about 184 graves in SouthPark and 62 in Grier Heights.

Johnson said some of the graves are marked but most aren’t. However, the group is determined to name and honor all of the people buried at both sites.

“We aren’t leaving anyone behind,” he said. “All those unmarked graves will have a memorial and it will list everyone’s name so that their identities will be known… We find new discoveries every day and we’ll continue sharing them as they come along.”

At the Grier Heights development, Dodson said the project will break ground in August and it won’t impede the foundation’s effort to restore the nearby cemetery.

He added that DreamKey is working on placing some decorative fencing near where the property lines meet. If community members would like to incorporate some memories of the area’s history into the development through artwork or other means, he’d be happy to hear their ideas.

The ultimate goal of the foundation is to turn both cemeteries into parks, Johnson said. Not an average park. Essentially an outside museum where folks can meander along the paths, sit along the edges and soak in the history.

The groups already started the design work and planning. They’ve placed some QR codes around the sites that people can scan to learn about the church, the congregation and the cemetery’s history.

More will be placed along the paths as the project continues. There also will be guided walking tours. If anyone is interested in helping with the restoration efforts, they can visit the foundation’s website, Johnson said.

The purpose of preservation is to keep stories alive, he added. The only way to do that is to have someone tell the stories and to have someone listen. And there’s no better way to have that dialogue then in a serene place of learning and love.

“It’s going to give people a sense of identity. A sense of pride. A sense of love. A sense that we can do a lot more together than separately,” Johnson said. “Once you go into that park, your mindset changes…That’s the beauty of it.

“When you’re in that space, it has a different feel. It feels sacred and it takes you to another space,” he said. “That’s why I said it feels so big. This history is bigger than all of us.”

Uniquely Charlotte: Uniquely Charlotte is an Observer subscriber collection of moments, landmarks and personalities that define the uniqueness (and pride) of why we live in the Charlotte region.