L.A. County wants to curb riskier fentanyl use. Its approach worries some activists

![Los Angeles, CA - May 19: Oscar Magana, 22, left, who struggles with mental problems but does not use drugs, sits in his tent as his step father, Johnny Roman, right, 58, who is addicted to meth, bipolar, manic depressive, and ADHD, puts bags of supplies for drug use in their tent encampment near Avalon Boulevard and East Florence Avenue in South Los Angeles Friday, May 19, 2023. The bags of supplies were distributed by a team from Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care Systems [HOPICS] and includes drug pipes, overdose reversal nasal spray, fentanyl test strips, wipes and educational materials are aimed at preventing infection and disease, and saving them from the fentanyl death crisis. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/YAX_STeuvIPNRleq5JR.xA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD05MzU-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/la_times_articles_853/bea6409ed8813b544e16d8c8012c2cda)

By a line of ragged RVs slung along 78th Street in South Los Angeles, a seven-member team passes out glass pipes used for smoking opioids, crack and methamphetamine.

Part of the front line of Los Angeles County’s offensive against the deadly fentanyl epidemic, the group hands out other supplies: clean needles, sanitary wipes, fentanyl test strips and naloxone, medication that can reverse an overdose.

But it’s the pipes that have people arguing. Not just cultural warriors, but activists with the same general aim to help the homeless population across the city.

These “harm reduction” supplies keep drug users alive and safe from infection and transmission of diseases including HIV and Hepatitis C, members of the outreach team say, and the pipes help them switch from injecting to the relatively safer route of smoking drugs.

Such giveaways are also aimed at building trust with users too ashamed or marginalized to seek medical attention, but who might want drug treatment down the road.

“It’s like a business card saying, ‘When you want hope, come to me,’” said Chris Mack, a longtime outreach worker with John Wesley Community Health Center, a clinic that refers clients to groups that distribute such supplies. “We’ve been killing people with this prohibition.”

Fentanyl, which is laced in everything from weed to heroin and meth, was present in more than half of the nearly 1,500 overdose deaths of homeless people in 2020-21. In response, Los Angeles County this year increased its harm reduction budget from $5.4 million to $31.5 million. Most of the money covers staffing and programs; officials said that only a fraction of county funds — no state or federal money — goes to pipes.

But the pipes tap a nerve, particularly in Skid Row, home to as many as 1,500 homeless people with substance abuse disorder and a wide array of drug recovery and prevention groups that serve homeless people throughout the city.

The 50-block downtown district saw the worst of the 1980s crack epidemic, and its converted flophouses and apartments are home to many residents who graduated from 12-step or other abstinence-based programs.

These and other residents say harm reduction, which in some form has a 40-plus-year history, albeit largely underfunded, hasn’t worked, and they see the pipes as hurrying homeless people along to their destruction.

“We’re trying to give them real help. We don’t give them drug tools,” said Skid Row activist Tony Anthony, whose video of pipe distribution was on local news.

“I wouldn’t get pipes to give them out myself,” said Skid Row organizer Manuel “O.G.” Campito, who went through recovery in the ’90s. “You know Dr. Kevorkian assisted suicide? That’s pretty much what it is.”

Studies have repeatedly concluded that harm reduction does not promote drug use, and a California naloxone distribution program reversed 173,948 overdoses since 2018, a spokesman for the state Department of Health Care Services said. L.A. community members reversed more than 5,000 overdoses with naloxone during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But even allies on Skid Row disagree on the pipes, and opinions have evolved.

United Coalition East Prevention Project, a 26-year-old Skid Row drug prevention organization, grew out of the abstinence model of its sponsor, Social Recovery Inc., but has evolved to a more holistic approach trying to change the social conditions underlying addiction. They provide overdose prevention education and partner with harm-reduction groups, said Charles Porter, the program director.

The group has fought liquor licenses and drug and pipe sales at Skid Row bodegas, but Porter said blocking businesses profiting off homeless people with substance abuse disorder is different than providing pipes to promote health and wellness.

Campito’s cleanup organization, Skid Row Brigade, works with Porter's organization but doesn't condone everything it does.

“It’s like a husband and wife: We don’t always agree,” Campito said.

“On Skid Row we can agree to disagree,” said Porter.

The pipes are the big draw in harm-reduction distribution. “Those are the crowd pleasers,” said Sandra Mims, a community health worker with the harm-reduction group LA Community Health Project, seated at her table at a North Hollywood access point one recent afternoon.

The latest wave of attacks on harm reduction by Republican politicians and conservative media has focused on “crack pipes" — a racist dog whistle, according to advocates. The kits include three glass pipes, with design variations to accommodate the ways crystal meth, crack and heroin are smoked, Mims said. Meth pipes are called “pookies” and crack pipes “straight shooters." Some pipes come with lollipops for dry mouth.

Most people with substance abuse disorder live on the county’s general relief, about $220 a month, Mims said, and even a $10 pipe is a stretch.

“We want to get them smoking; basically fentanyl is in everything,” she said. “Drug dealers put it to make it more addicting, and it’s so powerful it keeps them coming back. … The people dying are mostly Black youth.”

Smoking drugs poses less risk of overdose than injecting because the ingestion patterns are different. Opioid smokers take small amounts throughout the day to stave off withdrawal, while those who inject shoot the whole hit. In that case, if the dosage is off, or the drug contains higher than expected levels of fentanyl, users can go into overdose before they know what hit them. Some studies suggest that handing out pipes helps turn injection-only users into smokers.

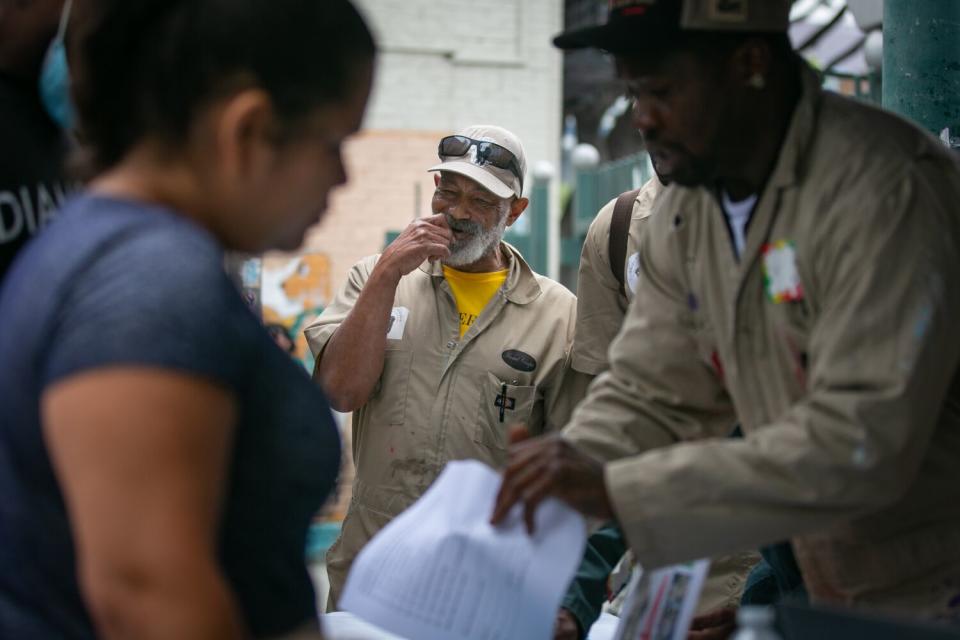

At the RV encampment on 78th Street, the outreach team from the Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System handed out the supplies.

Connie Lemos, 61, cried as she took a meth pipe. She had lived in the neighborhood 35 years and lost her home when her grandmother died. Her husband was deported. She's too embarrassed to buy a pipe at a store. "All the store owners know me," she said.

The team drove to a sidewalk tent train near Avalon Boulevard and East Florence Avenue. Flies buzzed over a pile of debris. A woman with a shopping bag picked her way through, waving her hand and crinkling her nose at the smell.

Johnny Roman, 58, stays in one of the tents with his stepson Oscar Magana. The 22-year-old, who has autism, doodled assiduously in a notebook as Roman listed his own mental health challenges: bipolar disorder, ADHD and depression.

“Two months ago a friend of mine died,” Roman said, examining a large scab on his hand. “ He picked up a baggy and [injected] the whole thing; it was fentanyl.”

Roman took a pookie. “It keeps us from doing it other ways,” he said.

At a backstreet once known as “Murder Alley,” a line of aging crack users sat on chairs along the wall. Juanita Richardson, 61, shuffled up on a walker to the outreach team.

“I want everything you guys have,” she said. “This fentanyl, it’s nothing to laugh at.”

Richardson is on methadone and said she doesn't use illicit drugs every day. She planned to sell the supplies: $10 for a pookie, $2 for a rig or syringe and $5 for a crack straight shooter, she said.

Oscar Arellano, program manager for the HOPICS team, said he does not condone selling the harm-reduction supplies, but sharing them is encouraged to make sure the whole community is protected.

“They’re the first responders,” Arellano said. “We’re not condoning. We’re supporting.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.