George H.W. Bush: Lessons from a life

George H.W. Bush, the 41st president of the United States, died Friday at age 94. Bush came from a life of privilege in the wealthy suburb of Greenwich, Conn., but spent the majority of his life in service to the country, from enlisting in the Navy after high school to leading the nation in wartime. Bush approached politics on a personal level and leaves behind friends and admirers from across the political spectrum in addition to a loving, devoted family. He was politically malleable, willing to compromise when necessary to advance his career, and he would help elevate forces he would come to criticize later in life. What follows are a few of the moments that helped define the man who was central to the last half-century of American politics.

Meeting Barbara

Perhaps the most important moment in Bush’s life happened when the 17-year-old attended his local country club’s Christmas dance. There he saw a girl in a red-and-green holiday dress who he learned was named Barbara Pierce, the daughter of a publishing executive who lived in nearby Rye, N.Y. Bush was introduced and the two danced, and they danced again the following night at another Christmas celebration in Rye. The two exchanged letters — Barbara was attending boarding school in Charleston, S.C. — and grew closer. Bush invited her to his senior prom at Andover, and she visited him in North Carolina during his naval training.

A year and a half later the two were engaged, Bush proposing to her during a visit to his family’s vacation home in Kennebunkport, Maine. They married on Jan. 6, 1945, in Rye, while Bush was waiting for his next military assignment. The two would remain married for 73 years, until Barbara’s death in April 2018, a partnership that ascended to the peak of American politics.

Shot down and rescued in the Pacific

Bush was a senior at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., hoping to enroll at Yale the next year, when on Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked. Instead of entering college, he joined the Navy as a seaman second class. Six months later, the 18-year-old was on his way to preflight training in North Carolina. On earning his wings, Bush, believed to be the youngest Naval airman in the service, was assigned to fly the TBF Avenger torpedo bomber.

Bush was assigned to the carrier San Jacinto in September 1944 when he took part in a raid on a Japanese installation on the island of Chichijima. On the approach, his plane was hit by antiaircraft fire but, in a cockpit filled with smoke, Bush managed to complete the bombing run. He flew off to sea and ordered his gunners to abandon the craft before bailing out himself. He was rescued by a U.S. submarine after spending a few hours in a life raft. His two crewmates were never recovered, and Bush would spend the rest of his life wondering if there was anything more he could have done to save them. (Official inquiries into the crash would confirm that there was not.) Bush returned to combat and would eventually fly 58 missions and log 1,228 hours, earning a list of commendations, including gold wings and a Distinguished Flying Cross.

His enlistment marked the start of a long career of service to the country, following in the path of his father, a U.S. senator, and setting an example for two of his sons, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and President George W. Bush. Bush would go on to serve as a member of the House of Representatives, United Nations ambassador, CIA director, vice president and president.

Lessons from the death of his daughter

George and Barbara Bush had six children together, four boys and two girls, but only five would survive to adulthood. Three years after George W. was born, in 1946, he was joined by a younger sister, Pauline Robinson, whom the family called Robin. At age 3, Robin was diagnosed with leukemia, for which there were limited treatment options at the time. She was treated at one of the nation’s premier cancer hospitals, Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City, where Bush’s uncle was president. Barbara had one rule: No tears in front of her girl. This proved difficult for Bush, who would continually have to step out of the room when visiting his daughter.

Robin died just before her fourth birthday. Both Bushes have talked about the darkness of those times and how much they had to rely on each other to get through it. “For one who allowed no tears before her death, I fell apart,” recalled Barbara to biographer Jon Meacham. “And time after time during the next six months, George would put me together again.” During their lifetimes, the Bushes raised nearly $90 million for oncology research at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and in 2013, Bush shaved his head in support of a member of his Secret Service detail whose 2-year-old son was battling leukemia.

Senate run sets a pattern of expediency

Bush’s first run for federal office came in 1964, when the Houston businessman won the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate race. In order for the Connecticut Yankee to establish his Texas bona fides, Bush aligned his positions with that of GOP presidential nominee Barry Goldwater. This required him to oppose elements of the Civil Rights Act on the basis of “states’ rights.” (Bush said he was “shocked” that his opponent, Democratic Sen. Ralph Yarborough, had voted in favor of the act, noting that it would require racial integration on the part of private businesses.) Bush lost the race, but in 1966, he won a seat in Congress from a Houston-area district, where he would later cast a vote for the Fair Housing Act. Bush was no racist, but he was a politician who at key moments in his career was willing to put expediency over principle.

When he was elected chairman of the Harris County Republican Party, he opted not to purge members of the ultraconservative John Birch Society from its ranks, not wanting to antagonize sympathizers. Serving as chairman of the Republican National Committee during the Watergate investigation, he publicly supported President Richard Nixon until the actual eve of Nixon’s resignation, making him one of the last to jump ship. As CIA director, Bush authorized a “Team B” analysis of Soviet military capabilities generated by conservative ideologues. The findings provided fodder for hard-liners who opposed arms treaties and who wanted to increase defense spending, but the Team B analysis was eventually proved wrong.

Slideshow: George H.W. Bush: A life in pictures >>>

Bush’s most significant capitulation came after the 1980 presidential primary campaign. Running against Ronald Reagan, the favorite of the conservative wing of the party, Bush staked out positions closer to the center. He decried Reagan’s tax-cutting agenda as “voodoo economics” and opposed a constitutional amendment banning abortion, a popular position among the right wing of the party, including Reagan. After he lost the nomination, Bush’s advisers decided the best path to the presidency was to be the second man on the ticket. In his pitch for the vice presidential nod, Bush signed off on Reagan’s entire platform, reversing many of his positions. He backed Reagan throughout his two terms, including during the Iran-Contra affair, where arms were sold illegally to Iran to secretly support right-wing rebel groups in Nicaragua.

Bush turned to conservative operatives Lee Atwater and Roger Ailes for his 1988 campaign, which was notable for what became known as the Willie Horton ad, attacking his Democratic opponent, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, with barely concealed racist imagery of a glowering black convict. After Bush won, Atwater became head of the Republican National Committee and launched take-no-prisoners attacks on Democrats, embarrassing Bush. On his deathbed, Atwater apologized to Dukakis for the “naked cruelty” of the Bush campaign. Ailes would become the head of Fox News, forging it into a conservative media powerhouse.

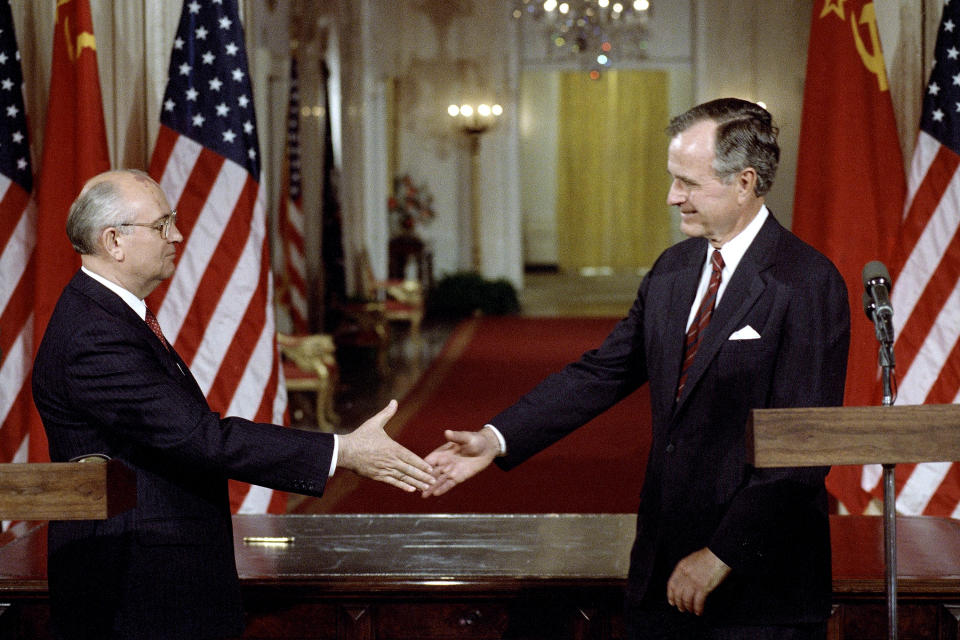

The Berlin Wall comes down

One of the underpinnings of Bush’s political philosophy was the importance of building personal relationships. This served him well in one of the signal events of Bush’s presidency, a joint news conference in December 1989 with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, on a ship, the Maxim Gorkiy, off the coast of Malta. Bush was cautious with Gorbachev but was receptive to the idea that his counterpart was serious about reforming and opening up Russia, a viewpoint not shared by everyone on Bush’s staff. The meeting laid the groundwork for subsequent negotiations, leading to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START. When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, Bush came in for some criticism for his low-key response, but his refusal to gloat helped keep Gorbachev’s trust. The two met again at Camp David the following year, and Bush was supportive of Gorbachev during an unsuccessful coup attempt in 1991. Russia has slipped back into authoritarianism and confrontation with the West, but during his term Bush did his best to promote better relations, and escaped the worst outcomes.

His father paves a path for him

Bush was successful in his second attempt at getting to Washington, winning a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966. He wrote House Minority Leader Gerald Ford seeking a position on the powerful Ways and Means Committee. Bush couched his request carefully, adding, “What you decide will be fine with me and I promise to work like hell to be a good member of whatever committee I get.” Bush’s father, Prescott Bush, then a U.S. senator representing Connecticut, made a couple of calls to leaders on Capitol Hill. The younger Bush would end up with a coveted seat on the House Appropriations Committee, a prestigious spot for any legislator, let alone a freshman.

The incident displayed how Bush used his privileged background, keeping it in the background but taking advantage of it at critical moments. His education couldn’t have been more representative of the East Coast elite, a trifecta of Greenwich Country Day School, Andover and Yale. But he declined to join the family firm on Wall Street, relocating to West Texas to work with a family friend in the oil business. Yet when he struck out on his own with an independent drilling company, Bush turned to the family Rolodex to raise money. He was a wealthy man by the time he turned to full-time politics.

His background came into play again in 1970, after a second failed bid for the U.S. Senate. Bush was set to become an assistant to Nixon when he made an alternate pitch: He could be the president’s United Nations ambassador. Bush didn’t have a background in international policy — after his appointment, an old friend asked him, “George, what do you know about foreign affairs?” — but Nixon liked the idea of having the son of a Connecticut senator representing him in the media circles of New York and took Bush up on his suggestion.

Meeting James Baker

When the Bushes moved to Houston in 1959, they struck up a friendship with a young lawyer named James Baker. Baker came from a prominent Texas family and had gone to prep school in Philadelphia before attending Princeton. Bush and Baker made a formidable pair, including on the tennis court, where they won a pair of country club doubles championships. When Baker’s first wife was dying from cancer, Bush and his family, drawing on their experience with Robin, supported him emotionally. Bush, six years older than Baker, considered it a “big brother, little brother” relationship.

Bush pushed Baker into politics, and Baker switched his party affiliation from Democrat to run Bush’s 1970 Senate campaign, serving later as undersecretary of commerce for President Ford and as his campaign manager in 1976. Running Bush’s campaign in the 1980 primaries, it was Baker who eventually urged his friend to withdraw, a move that likely garnered Bush enough favor with Reagan to earn the vice presidential spot.

It also helped Baker, who was brought on as Reagan’s chief of staff before transitioning to secretary of the treasury. Baker left that post to run his old friend’s 1988 campaign. Following his victory, Bush appointed his former doubles partner to secretary of state. The two didn’t always agree — Baker distanced himself from Dan Quayle, Bush’s pick for vice president — but he worked closely on international policy through Bush’s term in the White House. When George W. ran for president, Baker was his chief legal adviser during the Florida recount.

A promise he couldn’t keep: ‘Read my lips’

In accepting the nomination for president at the 1988 Republican National Convention, Bush made a promise that potentially won the election but cost him a second term.

“My opponent won’t rule out raising taxes,” said Bush. “But I will. And the Congress will push me to raise taxes and I’ll say no. And they’ll push, and I’ll say no, and they’ll push again, and I’ll say to them, ‘Read my lips: No new taxes.’”

Bush was able to honor the promise meant to appease skeptical conservatives for his first year in office, but faced with a budget deficit and Democratic majority in Congress, he had to admit in June 1990 that tax increases might be necessary. Bush felt that the pledge — the language of which had been debated by his campaign at the time of the speech before ultimately being left in — wasn’t as important as his belief that a budget deal was necessary to reduce the deficit and keep the government open. The tax increase enraged many in his party and likely resulted in a loss of credibility with voters during Bush’s reelection campaign. However, many experts also believe the deal helped prime the country for the economic expansion that unfolded under President Bill Clinton in the 1990s.

The deal was not the only legislative accomplishment Bush achieved working with the other side. He also supported and signed clean air measures and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, authored by Democratic Sen. Tom Harkin, which expanded rights for the disabled.

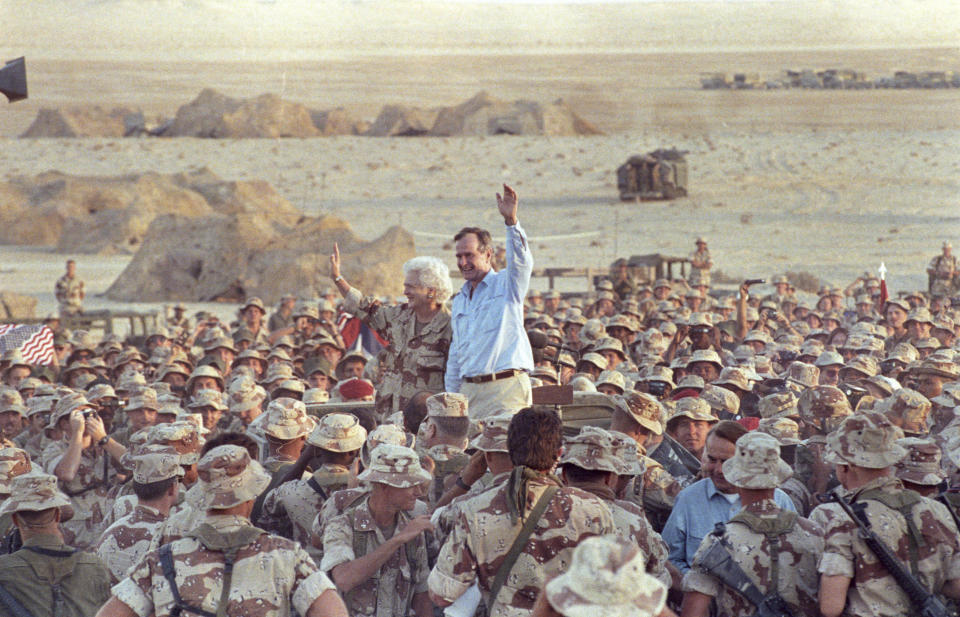

Invading Iraq but stopping short of Baghdad

In the largest American military campaign since the Vietnam War, a coalition of international forces led by the U.S. drove Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Army from Kuwait. Bush and his team strove to gather support from leaders across the globe as they considered their options in responding to Hussein. Baker was meeting with the Soviet foreign minister at the time, and the two issued a joint statement condemning Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, a surprising step as Iraq had been an ally and arms client of the Soviet Union. Bush worked hard to win international support, including from both NATO allies and Arab nations in the region.

Bush had planned to go in alone without approval from Congress or the United Nations if necessary, considering Hussein the “epitome of evil,” but Congress voted for what became known as Operation Desert Storm and a U.N. resolution gave authorization for a coalition strike if Iraq did not withdraw by a January 1991 deadline. The ground campaign was successful, lasting only a few days but achieving the objective of driving Iraqi forces from Kuwait and restoring the country to its leaders. There was a belief by some that the forces should push on and take Baghdad, deposing Hussein, but Bush believed that fell outside of the stated objective and an occupation would split the coalition. American troops returned home with Hussein still in power.

Bush’s secretary of defense, Dick Cheney, would go on to become George W. Bush’s vice president and one of the architects of the Iraq War. (During Desert Storm, Cheney had inquired about how many tactical nukes it would take to eliminate the Iraq Republican Guard.) The elder Bush supported his son in the war, despite his earlier reservations about attempting to capture Baghdad. After George W. Bush left office, his father was critical of Cheney, saying that he had become “very hard-line and very different” from his time working under him.

The relief trip with a former rival

After a brutal campaign in 1992, Bush’s political nightmare was realized when he became a one-term president. But on his final day in the office, he left a note for the new occupant, wishing him good fortune and informing Clinton he’d be rooting for him to succeed. Clinton called the note “gracious and encouraging,” and over the years the two former rivals developed a friendship. There was the 1999 trip to King Hussein’s funeral in Jordan, and then relief efforts for the Indian Ocean tsunami and Hurricane Katrina. On these trips, Bush grew to appreciate Clinton — how he insisted the 41st president take the plane’s stateroom and always waited to exit the jet together — even though he often shook his head at the 42nd president’s seeming ability to never stop talking.

After a joint award ceremony in 2006 in which Clinton said “I love George Bush,” his predecessor wrote to thank him for his kind words and also wished him good luck with Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential run, understanding that it would almost certainly involve disparaging his son’s presidency. “The politics between now and two years from now might put pressure on our friendship,” wrote Bush, “but it is my view that it will survive. In any event, I have genuinely enjoyed working with you. Don’t kill yourself by travel or endless rope lines.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump asks why Mueller hasn’t interviewed ‘hundreds’ of campaign staffers

George Conway: Republican Party has become a ‘personality cult’ under Trump

Trump administration defends asylum crackdown after judge’s ruling

An American killing: Why did the U.S. Park Police fatally shoot Bijan Ghaisar?

Cory Booker: I will ‘take some time over the coming months’ to consider 2020 bid