Gilbert: Why presidential campaigns heap attention on western Wisconsin

When President Joe Biden traveled to the small community of Westby this week, he followed a well-worn path to western Wisconsin, a key battleground region within this battleground state.

Wisconsin’s biggest western city, Eau Claire, hosted Vice President Kamala Harris, her Democratic running mate Tim Walz, and GOP vice presidential candidate JD Vance on the same day in early August.

Its second largest city, La Crosse, hosted Harris in April, and then former President Donald Trump on Aug. 29.

Western Wisconsin is attracting more attention in this campaign than its population alone might dictate.

But that isn’t exactly new.

This mostly rural, unusually swingy, highly strategic region is home to about 1 in 6 Wisconsin voters.

It is the closest thing in any battleground state to “Obama-Trump country” — home to almost 300 communities that voted for Democrat Barack Obama in both 2008 and 2012, then Republican Trump in both 2016 and 2020.

It’s also home to tens of thousands of voters who get much of their news and broadcast advertising from neighboring Minnesota, where Walz has served as governor since 2019. That makes this area a unique test of whether the selection of Walz provides any measurable boost to the Democratic ticket with rural voters.

In a broader sense, the region is a politically enticing one for both parties.

On the one hand, it has seen some of the biggest shifts in the country toward the GOP in the Trump era.

On the other, even amid those changes, it remains more competitive than its demographic makeup — overwhelmingly white, mostly rural and working-class – would suggest. Democrats have lost ground there. But there still aren’t many places in the middle of the country where they do better with rural white voters.

For decades, Wisconsin’s western flank has served as a crossroads for American presidential campaigns. This column is a look at some of the reasons why it could play an intriguing role in this one.

First, let’s define our terms.

What do I mean by western Wisconsin? There is no one answer, but for the sake of this analysis, I am defining it as primarily the three media markets that touch the state’s border with Minnesota.

That means the five northwestern Wisconsin counties within the Duluth, Minn. market; the seven Wisconsin counties within the Twin Cities, Minn. market; and the 12 counties in the larger La Crosse/Eau Claire market.

In addition, I am including two counties in southwestern Wisconsin that are part of the Madison media market but adjoin or are close to the Iowa border: Grant and Richland. (I could also include three other nearby counties — Iowa, Sauk and Lafayette; but I left them out because they’re a little further east and closer to the political pull of the Madison metropolis).

This leaves us with 26 mostly small counties containing 700 communities. These counties generated almost 540,000 votes for president in 2020, or almost 17% of the statewide vote.

The region is much more diverse politically than it is demographically.

It includes some of the most Democratic communities in Wisconsin (the cities of Eau Claire, La Crosse, Superior, Bayfield, Ashland, and Washburn), and a striking number of blue-leaning small towns.

It includes hundreds of very red towns and 11 counties that voted for Trump by more than 20 points.

And it includes some very purple places. Almost a fifth of its communities were decided by single digits in 2020, which is a lot in these polarized times for such a rural slice of the Midwest.

Finally, it has an undeniably “swing-y” history.

One-quarter of the region’s communities voted Democratic for president in 2012, then Republican for president in 2016, then Democratic for U.S. Senate in 2018, and then Republican for president in 2020.

Collectively, Obama won this region by about 7 points in 2012, and Republican Trump won it by more than 9 in 2016 and 2020.

How it votes in 2024 will be turn on some of the following questions:

Is there a Tim Walz factor?

Wisconsin voters are divided among seven media markets, the smallest two of which are centered in neighboring Minnesota. The seven Wisconsin counties in the Twin Cities market are mostly rural, but the biggest one, St. Croix, is home to growing Minneapolis/St. Paul exurbs on the Wisconsin side of the border. Trump carried this market by almost 20 points in 2020.

The Duluth market is made up of five Wisconsin counties in the northwest corner of the state, home to such historically blue communities as Superior, Ashland, Bayfield and Washburn. Trump lost these counties by a combined 4 points in 2020.

Voters in both places get a lot of their news and advertising from Minnesota. There is arguably a Minnesota influence on some border counties in the La Crosse market as well.

Does that mean the presence of Minnesota’s governor on the ticket might help Democrats in Wisconsin this November?

There are two big caveats here. One is that there is little history of running mates having much influence on the presidential vote, even in a vice-presidential candidate’s home state (Wisconsin Republican Paul Ryan’s presence on the GOP ticket in 2012 is an example). Another caveat is that these two Minnesota markets are home to only about 7% of Wisconsin’s voters.

But even the most marginal factors in a closely divided state such as Wisconsin can matter. These two Minnesota markets generated almost as many votes in 2020 (about 235,000) as the city of Milwaukee, and Milwaukee’s voting and turnout trends get a lot of justifiable attention in presidential races.

More: Wisconsin voter ID law still causing confusion, stifles turnout in Milwaukee, voting advocates say

Democrats lost the Minnesota markets by a combined 14 points last time. If Walz were to help the ticket shave, say, 4 points off that deficit, that would be a net gain of more than 9,000 votes in a state decided last time by less than 21,000 votes.

If Walz turns out to provide any battleground bonus to Harris, this is probably the first place to look for it.

Which way is the region now swinging?

Western Wisconsin has a history of partisan turns.

In presidential voting, it shifted dramatically toward the GOP in 2016. Of the 537 Wisconsin cities towns and villages that swung from Obama to Trump, more than half (282) were in western Wisconsin, as I have defined the region here.

The very competitive La Crosse/Eau Claire media market is the only one in the state that voted twice for Obama and twice for Trump.

Between 2016 and 2020, the swings within this region were a lot smaller, and they occurred in both directions. Trump gained even more ground in smaller counties like Richland, Trempealeau, Jackson and Grant, but lost ground in the region’s biggest counties: La Crosse, Eau Claire and St. Croix, mirroring a pattern seen throughout Wisconsin. The northwest corner of the state swung back toward the Democrats a little.

How much ticket-splitting will we see?

Western Wisconsin also has a history of supporting different parties in the same election.

Two races where this could come into play are the U.S. Senate race pitting incumbent Democrat Tammy Baldwin against GOP challenger Eric Hovde, and the Third Congressional District race between Republican U.S. House incumbent Derrick Van Orden and Democratic challenger Rebecca Cooke.

Consider the history of split outcomes here.

In 2014, western Wisconsin’s Third Congressional District voted Republican for governor, but Democratic for House.

In 2016 and 2020, it voted Democratic for Congress but Republican for president.

And in 2022, it voted Republican for Congress but Democratic for governor.

In each case it was the only one of the state’s eight House districts with a split outcome.

And the last time Baldwin was on the ballot — 2018 — she won more than 150 communities in western Wisconsin that voted for Republican Gov. Scott Walker, a much higher incidence of ticket-splitting than in the rest of the state.

Two decades ago, in the elections of 2000 and 2004, western Wisconsin attracted an astonishing level of very personal presidential campaigning, with the candidates crisscrossing the countryside on buses and battling over the same tiny towns.

A big reason for that was that Iowa and Minnesota were also battlegrounds back then, so western Wisconsin was a “three-fer.”

Today, Iowa and Minnesota are no longer true battlegrounds. But because there are fewer battlegrounds nationally, Wisconsin looms just as large.

The state’s western counties are anything but a monolith. The northwest, on Lake Superior, and the southwest, on the Upper Mississippi, are different places with different political histories.

But collectively, this region has a political diversity unusual for the rural Midwest. The fact that Democrats were so competitive in its small towns played a huge role in keeping the state blue in 2000 and 2004. And its swing toward Trump was more than enough to turn the state red in 2016.

It should be a big part of the story again in 2024.

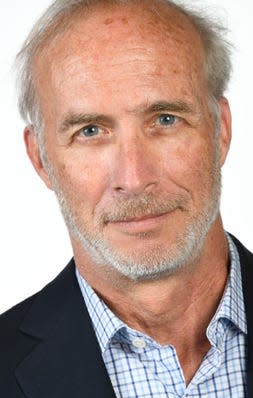

Craig Gilbert provides Wisconsin political analysis as a fellow with Marquette University Law School's Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education. Prior to the fellowship, Gilbert reported on politics for 35 years at the Journal Sentinel, the last 25 in its Washington Bureau. His column continues that independent reporting tradition and goes through the established Journal Sentinel editing process.

Follow him on Twitter: @Wisvoter.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Western Wisconsin attracts intense election attention. Here's why