‘Having a good time is a political act.’ Miami hip-hop is about more than dancing

On the surface, Miami is a paradise.

The beaches, the palm trees, the weather all have created an outsider’s perception of perfection.

Even in paradise, however, exist the same underlying issues that gave rise to hip-hop amid the urban decay of the South Bronx 50 years ago. And much like their northern counterparts, Miami hip-hop artists have consistently punctured the facade of the American Dream. The rappers made in Dade during the first 50 years of hip-hop – from Uncle Luke to JT Money to Trick Daddy to Trina to Rick Ross to Denzel Curry to City Girls to King Hoodie – have used their art to reflect an experience of growing up in a Magic City where the magic rarely extends into all neighborhoods.

As Regina Bradley explains in her seminal work “Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of Hip-Hop South,” Southern hip-hop challenges the narrative that racism ended with the Civil Rights Movement and dispels the monolithic image of the South.

‘It’s like paying homage to your city’: How a local hip-hop sound got Miami to dance again

“Hip-hop serves as a powerful intervener to address the continuously shifting negotiations of power, identities and communities of Black people in the South,” Bradley wrote in “Chronicling Stankonia.”

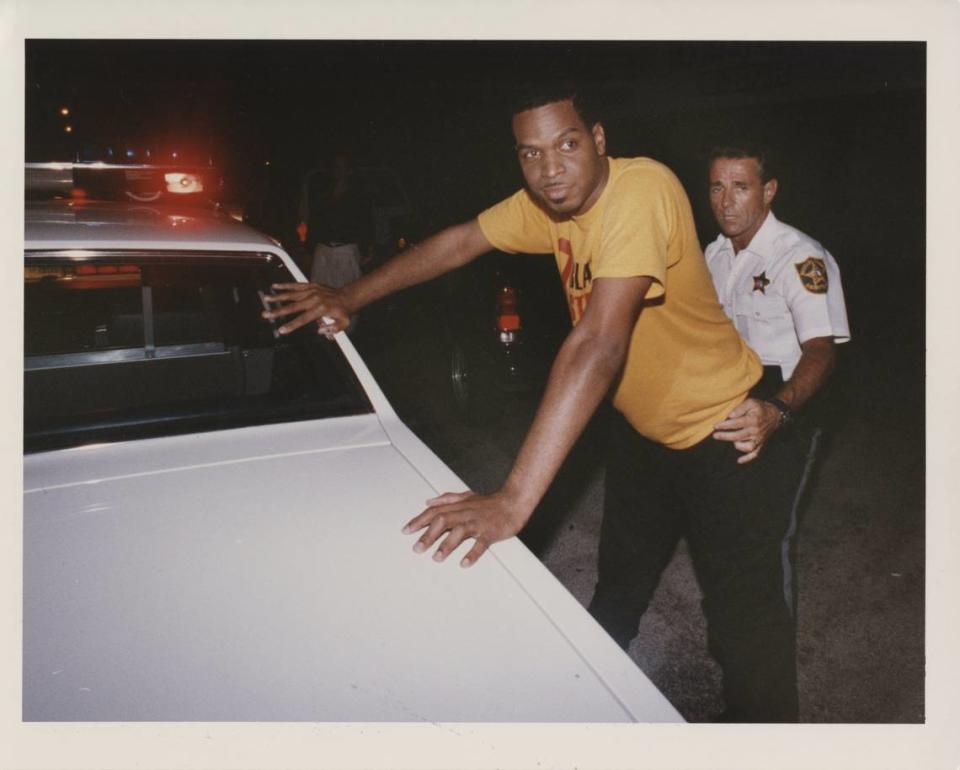

Similar to how the blight and neglect in the Bronx became a catalyst for the birth of hip-hop, the genre found its way to Miami following decades of displacement, neighborhood demolitions, police killings of unarmed Black men, riots and immigration policies that clearly favored newcomers of a lighter hue. Add to that the uptempo rhythms from the Caribbean and Latin America and what emerges is an energetic release in the form of bass music that sprouts up in the ‘80s. The raunchy yet satirical lyrics that overlaid the thumping 808s gave rise to a First Amendment case, transforming Uncle Luke, a record executive turned leader of the 2 Live Crew, into a free speech warrior.

“When you’re black and you’re from a place like Liberty City, just showing the world that you’re having a good time is a political act,” Uncle Luke, born Luther Campbell, wrote in his autobiography, “The Book of Luke: My Fight for Truth, Justice, and Liberty City.” When a judge declared 2 Live Crew’s music obscene, he chose to stand up “because I had the only black-owned label, I was the only one who could fight this fight. If I didn’t stand up, corporate America would keep trying to censor all of us.”

Here are 25 songs that define South Florida hip-hop

What Campbell did gave rise to a generation of rappers who gave an unfiltered, uncensored view of what it was like to be from Miami. Poison Clan and Trick Daddy took this a step further, painting portraits of how institutional neglect leads to a life in the streets.

“I used to say Miami is like a third world country,” said Jeffrey Thompkins, better known as JT Money. The former Poison Clan member emphasized that when 2 Live Crew’s Mr. Mixx signed them to Luke Records, the group went from “the streets to the beats,” he recalled.

“We suffered for this city being built,” Trick Daddy added. “We made sure that when we made our music — no matter if it was fast or slow or the bass hit — we always told a story because we had no way of getting our videos played because they didn’t want to hear that from us: they thought we were some ‘ole country bumpkin, gang-bangin’, drug dealin’ dudes. They didn’t know our struggle, they didn’t know our story because the world wasn’t so connected.”

‘Rep Miami like no other place’

Both Trick Daddy and JT Money got their start in bass music, a subgenre considered by some to be demeaning to women. And while bass certainly may have had its moments, outsiders failed to understand that Miami creates a different breed of women. Enter Katrina Taylor, AKA Trina.

“I discovered and birthed a whole world full of bad chicks,” Trina said. “Everybody, all the girls that came up, they all the baddest chick now. And when I say the baddest chick – the baddest b----, bossed up – for me, that means staying true to yourself and who you are. That’s standing in self-confidence. That’s standing in yourself and trying to be the best women you can be for yourself.”

Her music spoke to independence. Autonomy. Self love. Sure, Miami’s heat means women might be more scantily clothed but that doesn’t invite the perceived ownership inherent in misogyny.

“People wanted women rappers to be more conservative,” Danyel Smith, author of “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop,” told the Miami Herald in 2019. Trina, she explained, isn’t “nervous or tentative” which, in turn, “gives listeners that same attitude and confidence.”

Carol City’s Rick Ross inspired a similar confidence for his fans. Unlike his predecessors, Ross didn’t utilize the bass sound. He charted his own path, fashioning himself into a larger-than-life superhero whose documentation of the grim realities of his hometown – “Back in the day I sold crack for some nice kicks/ skipping school, I saw my friend stabbed with an ice pick,” he rapped on 2009’s “Valley of Death” — allowed him to become the boss that his name inspired. Owning countless Wing Stops, the biggest residential pool in the U.S., and even authoring a self-help book hasn’t prevented Ross from remembering where he came from.

“Being from Miami,” Rick Ross, born William Roberts II, said in 2019, “that’s something we were raised to learn: rep Miami like no other place. It don’t matter — 305, Dade County — and that’s something that I always applied.”

What’s next?

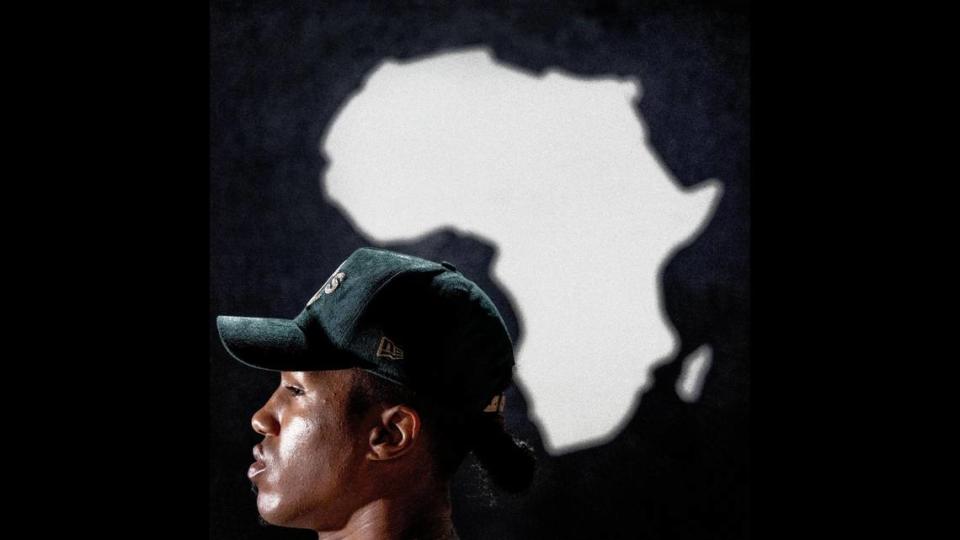

The more current generation Miami rappers – from Denzel Curry to the City Girls to King Hoodie – continue to wave that 305 flag in ways that pay homage to the history while, like Ross and Trina, blazing their own path. With Curry, it’s in his versatility: the SoundCloud Rap pioneer can rap about his love for the “Zuu,” a nickname for his birthplace of Carol City, just as well as he can cover Rage Against the Machine’s “Bulls on Parade” on the perils of the American justice system.

“My brother died because of s--- like this,” Curry told the Miami Herald in 2020 following George Floyd’s murder. “That’s why I’m saying and doing my part, because I don’t want this s--- to keep happening.”

With the City Girls, clear descendants of Trina, the magic is in their continued pursuit of sexual liberation but also debunking the “one rap queen” narrative that’s existed since the genre’s inception. Lines like JT’s “Give me the cash, f*** a wedding ring” or Yung Miami’s “He can’t come around without that cabbage” showcase how they get their piece of the patriarchy.

“I put our culture and our music” on wax , Jatavia Johnson, or JT, said in “The City Girls Documentary: Point Blank Period.”

“The reason why our mixtape doing so good is because every girl can relate to it,” Caresha Brownlee, known as Yung Miami, added. “Every song on there is relatable. Who the f--- want to talk to somebody who don’t got no money?”

And with King Hoodie, an independent rapper hailing from North Miami Beach, it’s in authenticity. Absent in his music, which he describes as for “the people who are still unseen,” are the flexes about his cars or jewelry or bank account. In his mind, hip-hop’s opulent displays of wealth alienates listeners. What King Hoodie experienced as a youth — from bullying to living in an abandoned building to racial profiling — wasn’t for nothing; there’s a message in there for somebody.

“I had always known that my organic story, me being real to myself was going to pull something out of you,” said the Puerto Rican-Haitian artist born Jean-Raymond Jean Philippe.

“Our job right now as story tellers are to know the history and apply it to the modern,” King Hoodie said.