The hidden victims of opioid addiction: Children in foster care

The surge in opioid abuse across the U.S. has claimed many victims, often young adults in the prime of life. But there are other victims as well, typically hidden from view: the children of addicts who are either orphaned or taken from parents who are unable to care for them. After declining for years during and after the Great Recession, when states cut their social service budgets, the number of children in the foster care system, more than half a million, has been creeping back up again — with potentially serious long-term consequences for the children and the rest of society.

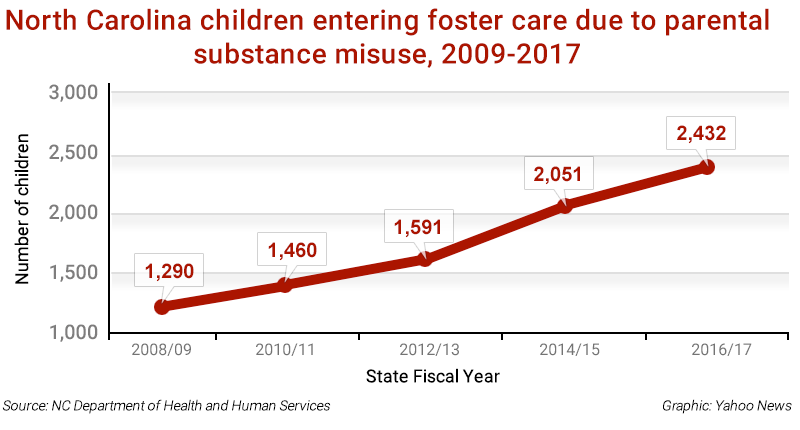

A report out of North Carolina recently demonstrates the effects of the addiction crisis. NC Child, a nonprofit children’s advocacy group, found that in the 2016-2017 fiscal year, 39 percent of children — up from 26 percent just 10 years prior — entered the state’s foster care system because of parents’ problems with substance abuse.

“These statistics definitely translate nationwide,” said Whitney Tucker, the report’s research director, who noted that a number of other states have also reported rising foster care entry rates because of the opioid epidemic. The Department of Health and Human Services reported a nearly 7 percent spike in the number of children in foster care just from 2013 to 2015, with parental substance use cited as a factor in about 32 percent of cases — up from 22 percent in 2005.

“We’re seeing [this] increase … at the same time as we’re seeing a rapid increase in opioid misuse, hospitalizations and deaths,” said Tucker.

Opioids, both prescription medications and street drugs like heroin, are now the leading cause of accidental deaths in the U.S., killing more than 42,000 people in 2016 — more than any year on record, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 40 percent of that number involved prescription opioids, and more than 2 million Americans are estimated to have a problem with opioids, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

While opioids are at the forefront of the current drug crisis, experts have different opinions about whether they are more likely to result in a loss of parental custody than other substances, such as alcohol.

Maria C. Inoa, a licensed social worker in Florida, said in her experience working with families affected by addiction, “opioid addiction ravages families much worse than alcoholism. … The parent may be able to complete detox and a substance-abuse program, but many relapse and end up losing custody of their children again. I see a lot of older siblings who become ‘parentified,’ in that they end up raising their siblings because their parent is either intoxicated in some way or they are gone on binges for periods of time. Opioid addiction is extremely severe and I see parents much more desperate to feed their addiction versus alcoholism.”

Ashley Hampton, a psychologist who evaluates kids and adults in the child protective services system, agreed, adding that any substance use disorder can be destructive to families — especially financially. The addicted parent uses his or her money for drugs and neglects to pay bills, buy food and hold a job.

But “using opioids tends to be pretty easy to hide, while drinking alcohol is often difficult to hide,” said Hampton. “There are many different types of opioids and many ways to obtain them, including buying heroin from a drug dealer on the street, visiting the doctor’s office to ask for a painkiller prescription, using them in the hospital under doctor’s orders after a surgery, becoming a patient at a methadone clinic. … With the variety of ways to obtain opioids in contrast to alcohol, there are a variety of patients and families being affected by the addiction.”

Moreover, in contrast to alcohol, opioid addiction may “happen quickly, and the road from prescription or recreational use to addiction is swift, and often fatal. … Alcoholism will kill people, but often this is a slow death,” said Dara Gasior, director of assessment and training at High Focus Centers in New Jersey.

But Matt Pinsker, a criminal defense attorney who focuses on drug cases, said that in his experience, addicts — irrespective of their drug of choice — are likely to neglect their children. “The addict becomes [so] fixated on getting the next ‘fix’ that it comes at the expense of children’s health and safety,” said Pinsker. “For example, a 5-year-old is left home alone while dad is panhandling to get money to purchase liquor, or an infant is suffering heat exhaustion in a hot parked car while dad is passed out at the steering wheel with a heroin needle in his arm.” Pinsker said he is also aware of an increasing number of parents who drive under the influence of drugs with their children in their cars.

All of these factors contribute to more foster care placements. As of 2015, about 450,000 children were living in foster care in the U.S., and more than 110,000 others were waiting to be placed, according to the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). About 20,000 will age out at 21 (or at 18 in some states) and leave the foster care system without being adopted, putting them at about a 50 percent greater risk of homelessness and a 25 percent greater risk of addiction compared with children who grow up in stable homes. Men are also at a 40 percent greater risk of incarceration when they’ve aged out of the foster care system, according to the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption.

From a historical perspective, though, Christopher Wildeman — professor of policy analysis and management at Cornell University — said the highest rate of foster care intake in the last several decades was actually in 2007, when roughly 15 percent more children were served than in 2016 (783,000 in 2007; 687,000 in 2016). The yearly change in the number of children served by the foster care system actually declined faster during the Great Recession (about 4 percent per year) than it has risen in the last couple years (about 3 percent per year). “So while there certainly has been a recent increase in foster care caseloads that is likely partially attributable to the opioid crisis, this change has actually been well within what we would expect to see historically and may actually reflect getting back to a ‘normal’ pre-Great Recession level — when the system wasn’t as severely underfunded,” said Wildeman.

There is no one-size-fits-all experience or solution when an investigation into a child’s welfare begins, experts say. But when a child is taken into social services, they are placed in the care of others while a parallel process is set in place for timely reunion with their parents. And many variables will influence the reunion process, both positively and negatively, said Dr. Charles Sophy, medical director for the L.A. County Department of Children and Family Services.

“Depending on where a parent is in their addiction, and where they are as far as their ability to parent on every level, dictate the outcome of that process,” said Sophy. “Typically, parents are given about six months to demonstrate, through their behavior, their commitment to sobriety and stability in order to reunify with their children.”

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 51 percent of children who exited foster care in 2016 were reunited with their parent(s) or primary caretaker(s). The length of a child’s stay in foster care varies greatly in the U.S., according to the Child Action Network, but the average period is two years.

“This cycle is vicious,” said Sloan Crawford, a foster care parent in North Carolina who, along with his wife, has fostered five children and provided short-term care for five others. “[And] foster care is a silent story. It’s hard to tell it — there is so much that must remain private to protect the child. But it’s never their fault. These are not ‘bad’ kids. … All children deserve love and the right to a safe, healthy home.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ex-NSA official: Russian hack of Democrats was ‘assembly line operation’

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: It’s ‘preposterous’ to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

‘I thought I would never see him’: Asylum seeker and son reunite after border separation

After Trump’s defense of Putin, sighs of resignation — but nobody’s resigning (yet)

Trump and Putin: The admiration is mutual, the benefits one-sided

Photos: Candlelight vigil in front of White House is part of nationwide protest