How President-elect Joe Biden will govern — if he can govern at all

WASHINGTON — Once upon a time — as in a few weeks ago, when the polls were exuberantly predicting a Democratic landslide — America’s pundits took to musing about how Joe Biden could soon become the next Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“COVID-19 and the disastrous White House response [appear] to have dramatically widened Biden’s pathway to the presidency, making the matter of moderation and electability seem, at least for the time being, almost moot,” wrote Gabriel Debenedetti in New York magazine. “[Now Biden] considers the present calamity and plots a presidency that, by awful necessity, he believes must be more ambitious than FDR’s.”

Biden did little to discourage the comparisons. He started to reread Jonathan Alter’s “The Defining Moment,” a book about the pivotal first 100 days of Roosevelt’s tenure. He traveled to Warm Springs, Ga., where FDR first went to convalesce from polio and where he died in 1945, to extol the “lessons” his predecessor “used to lift a nation: humility, empathy, courage, optimism.” And most of all, the 77-year-old son of Scranton, Pa., predicted, again and again, that the pandemic would be for him what the Great Depression was to Roosevelt: the test that would supersize his presidency.

“I’m kind of in a position that FDR was,” Biden told the New Yorker. “It’s probably the biggest challenge in modern history, quite frankly,” he added on CNN. “I think it may not dwarf, but eclipse, what FDR faced.” As a result, Biden told donors a few weeks later, “I think people are realizing, ‘My Lord, look at what is possible,’ looking at the institutional changes we can make, without us becoming a ‘socialist country’ or any of that malarkey.”

He went on to tack further left than any Democratic nominee in decades, embracing a multi-trillion-dollar progressive agenda: massive infrastructure investments to combat climate change; a carbon-free power grid by 2035; a comprehensive “public option” for health insurance; a lower age of enrollment (60) for Medicare; and equally expansive reforms around immigration, labor, education and racial justice.

Then came the actual election. What Biden never said — perhaps because he expected to have a healthy congressional majority to work with, or perhaps because it simply didn’t sound as stirring — was that his Rooseveltian aspirations were wholly contingent on something he couldn’t control: the composition of the U.S. Senate and the identity of the majority leader.

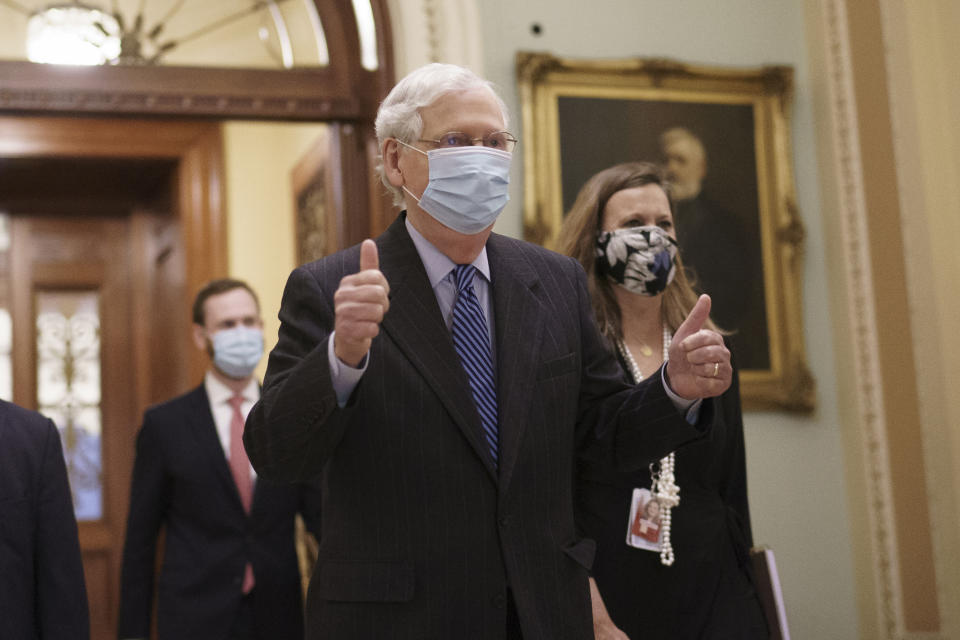

Now, Republican victories in states Democrats had hoped to win — Iowa, Maine, Montana, South Carolina, Texas and likely North Carolina — may have put the Senate out of reach. In the House, Democrats were sure they would expand their majority; now they are on track to lose seats instead. Theoretically, the uncalled Alaska Senate race and a pair of uphill Jan. 5 Senate runoffs in Georgia could still give Democrats a narrow majority, if they pull off upsets in at least two of those three contests. But even then, Biden would lack the 60-vote supermajority that enabled Obama to pass healthcare reform, and he is reluctant to eliminate the filibuster. The odds are that Mitch McConnell will still run the show on the Senate side of the Capitol.

That spectacle will not resemble a buddy comedy. “Tuesday’s results mean neither party is going to be in a mood to find common ground,” said Republican strategist Colin Reed. “The left will lament the lack of a more bold, progressive agenda, and on the right, the populism and principles of the Trump era were validated, even if its namesake does fall short.”

“Assuming Biden wins, we’re in for deadlock at best,” agreed diplomat Aaron David Miller on Twitter, adding that as president, Biden would be “a transitional figure” — even if Tuesday’s polarized results raised deep questions about what kind of future the nation will be transitioning to.

Miller, who worked on Israeli-Palestinian affairs for Bill Clinton and presumably knows a thing or two about political stalemates, predicted that most of the “big transformative moves” progressives want from a Democratic president — an expansion of public health insurance, a Green New Deal — stand no chance of being enacted.

It is true Biden earned more popular votes than any other candidate in U.S. history, and his Electoral College tally could still cross the symbolic 300-vote threshold that President Trump defined as a “landslide” in 2016.

“What’s becoming clear each hour is that a record number of Americans of all races, faiths religions chose change over more of the same,” Biden said Friday in Delaware. “They’ve given us a mandate for action on COVID, the economy, climate change, systemic racism. ... We have to remember the purpose of our politics isn’t total, unrelenting, unending warfare. No — the purpose of our politics, the work of the nation, isn’t to fan the flames of conflict but to solve problems.”

Yet even Democrats are unsure how many problems Biden will be able to solve. Trump’s loyal followers also came out in record numbers, forcing a closer finish in crucial states than anyone outside the MAGA bubble foresaw. So close, in fact, that Trump will continue to shout, falsely, that the election was stolen. So close that “his” half of the country may continue to believe him.

And so on Jan. 20, 2021, Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. could become the first Democratic president since Andrew Johnson in 1865 to take office alongside a Republican Senate — and the first of either party to face, all at once, a cutthroat majority leader ready to stop him from passing progressive legislation or confirming liberal judges; a hostile 6-3 Supreme Court majority that seems ready to overturn his executive orders; and a shameless predecessor ready to spread lies about his legitimacy, with a spellbound base still ready to swallow every word.

Not to mention the restive progressive wing of Biden’s own party, which is resistant to any signs of centrism or compromise. As a candidate, Biden vowed in one breath to resurrect a lost ethos of decency, civility and bipartisanship; in the next, he insisted he was merely a bridge to “an entire generation of leaders” who represent “the future of this country.” He never resolved that contradiction — between restoration and transition, nostalgia and progress — but the dynamics now in place will hamper his ability to do either.

“When you put this election on top of a political system that leans toward division — from institutional dynamics like gerrymandering and a partisan media to a radical Republican Party — Biden will be governing in some tough terrain,” said Princeton history professor Julian Zelizer. “There are real limits to how far he can go.”

The New Deal, in other words, is no longer the model for how Biden will govern. The question is whether he can govern at all.

Biden still shares one thing with FDR, unfortunately. He will inherit the presidency in the depths of what he’s already described as a “dark winter” — perhaps the darkest since the Great Depression.

Asked late last month to list “the three or four things that are at the top of Joe Biden’s first-term agenda,” he didn’t hesitate: “Get control of the virus,” he said. “Get control of coronavirus. Without that, nothing else is going to work very well.”

COVID-19 is currently infecting more than 100,000 Americans and killing upwards of 900 each day, numbers that are likely to continue climbing as colder weather and holiday celebrations tempt more and more people to socialize indoors. Even with Republican control of the Senate, Biden should be able to implement at least some of his plan to slow the virus’s unchecked spread: encouraging a nationwide mask mandate, investing in rapid testing and expanding contact tracing, among other measures.

Yet the pandemic is not the only shadow over the future. As president, Biden must also contend with COVID-19’s ripple effect on the economy, and Washington’s failure to address it sooner.

The statistics are sobering. Unemployment currently stands at 7.9 percent, three and a half points higher than when Trump took office. The so-called real unemployment rate — which includes Americans who are unemployed, underemployed and marginally attached to the workforce — is nearly 13 percent. If you count as unemployed everyone who is looking for a full-time job that pays a living wage — but who can’t find one — that number more than doubles to 26.1 percent. Expand the definition to any American over 16 who isn’t earning a living wage, and the rate doubles again, to 54.6 percent.

Unemployment has been trending downward in recent months. Growth has been picking up. Yet America is still far worse off than it was this time last year, and the massive influx of federal money that has been propping up the U.S. economy is about to peter out. Washington has already spent 90 percent of its initial $2.7 trillion in pandemic relief. Without congressional action, protections for renters, student borrowers and jobless Americans will expire by the end of the year.

As unpaid utility bills come due, millions risk losing power and water. Thirty million to 40 million face eviction. A million travel-industry jobs are threatened. Eighty thousand bus drivers have been furloughed. Hunger is rising dramatically. Without more government assistance, 40 percent of all restaurant owners nationwide say they expect to go out of business by March; two in three U.S. hotels may not last another six months. Nearly 100,000 businesses have already closed forever because of the pandemic.

Much of this devastation could have been mitigated if Trump and Congress had managed to agree on a second round of stimulus. But while a $2.2 trillion aid package breezed through the Democratic House earlier this fall, conflicting political agendas prevented House Democrats, Senate Republicans and the Trump White House from settling on a bipartisan solution. Now, according to a report in the Washington Post, administration insiders are predicting Trump will lose interest in passing more pandemic relief before leaving office — and Senate Republicans, about to shift into deficit-hawk mode under a Democratic president, would prefer to saddle Biden with the responsibility for another multitrillion-dollar spending bill.

“I don’t think [Trump’s] got much interest in stimulus,” said Casey Mulligan, a former senior White House economic official. “He doesn’t like to give anything for free, and I don’t think he’s going to start now. That’s not his style.”

And so — several months overdue, with millions suffering more than necessary — the stimulus may be the first of many four-dimensional puzzles Biden has to solve.

McConnell won’t make it easy. Whether it comes to confirming judges or passing legislation, the Senate is critical to a president’s success. Biden surely recalls the trench warfare that stymied Obama after Republicans recaptured the Senate in the 2014 midterms. Before that, as a member of that body himself, Biden watched as Democrats took power in 2006, eventually mustering sufficient votes for a spending bill to override President George W. Bush’s veto, the strongest rebuke of a president that legislators can unleash.

In short, much as he may pay lip service to the American system of checks and balances, no president wants to wrestle with a Senate dominated by the opposition party — least of all a Senate controlled by McConnell, a master of obstruction who stalled President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court for nearly a year.

But there are a few factors that could mitigate McConnell’s intransigence. The difference between the standing Republican and Democratic proposals is only about $400 billion — a large number, but relatively minor compared with the overall price tag for each package. Acutely aware that struggling Americans need help, and perhaps eager to show that they can transcend the divisiveness of the Trump era, the House and Senate could bridge their differences, as a show of bipartisanship to mark the new administration.

To help things along, Biden will likely appoint a treasury secretary more skilled at the art of political negotiation than Steven Mnuchin, the former movie producer Trump selected for the job. And he will have a new chief of staff to replace Mark Meadows, the blustering tea party stalwart who was always an awkward fit for that role.

Some observers believe that McConnell may be more willing to negotiate now that he no longer has to placate Trump ahead of the presidential election. The farsighted majority leader has to think about 2022, when 22 members of his Senate GOP conference will be up for reelection.

“The Biden experience will be similar to [Ronald] Reagan, in that both controlled one house of Congress but not the other,” said Bruce Bartlett, who served as a top adviser to Reagan, a Republican president forced to contend with a Democratic House for his entire eight years in the Oval Office. “This means that a president can always get some legislative action on his proposals, at least hearings and a vote. That keeps the ball rolling.”

Biden, meanwhile, will be desperate to show that his dealmaking muscles have not atrophied, having run on his ability to reach across the aisle, almost derailing his campaign during the Democratic primary by boasting about his ability to work with Southern segregationists early in his Senate career.

“He does generally and genuinely want to be a president for all Americans,” said a former Biden aide who worked closely with the vice president. “Some of that goes back to when he won his first Senate race in ’72. He beat a very popular incumbent Republican, and he came up in a state where there were plenty of Republican senators and governors, and there were plenty of Democrats. People found a way to work together.”

As an example of how deep Biden’s desire for consensus runs, the former aide noted Delaware’s unique tradition of gathering in rural Georgetown the Thursday after Election Day — known as Return Day in the state — to hear the town crier announce the results.

“The candidates literally ride together in a carriage and bury a hatchet,” the aide said. “There could not be a better personification of what [Biden] thinks is important than this quaint, super-Delaware tradition. So how can you possibly make that very symbolic parade a reality in this climate? Because that’s ultimately what in his heart of hearts he wants to go for.”

In that spirit, Biden will lean on his long-standing relationship, even friendship, with McConnell. In 2011, Biden marveled at the size of the crowd that had come to hear him speak at McConnell Center in Kentucky. “You want to see whether or not a Republican and Democrat really like one another,” Biden said. “Well, I’m here to tell you we do.” McConnell has since called Biden a “trusted partner” and, this week, an “old friend.” During the Obama years, the two men negotiated the 2012 “fiscal cliff” deal to raise taxes and cut spending, among other agreements that angered progressives.

Biden’s long career in Washington has made a pragmatist of him. “I never expect a foreign leader I’m dealing with, or a colleague, a senator or a congressperson, to voluntarily appear in the second edition of ‘Profiles in Courage,’” Biden told the New Yorker. “So you gotta think of what is in their interest.”

Republicans largely concur. “Biden handles negotiations [as] a very practical matter. ‘You know, we gotta get a deal. You have to trust me when I tell you what I can and can’t do,’” McConnell’s former domestic policy adviser Rohit Kumar recently told Politico. There was “a pretty stark contrast [between] how Biden and Obama handled the negotiations.”

Any stimulus deal would be viewed as a bipartisan victory for Biden, which McConnell would not grant Obama, whose defeat for reelection he notoriously said would be his top priority. But one Democratic Senate staffer, who asked that her name not be used because her employer had not authorized her to speak to the press, predicted that “the forces of the economy will get away from McConnell.” Cold weather and rising economic misery will ratchet up the political pressure, she said, and a substantial coronavirus relief package — like the one that easily passed in March and was expected to be the first of several such measures, as opposed to a one-time life preserver — will be hard for Republicans to block.

McConnell, of course, will demand concessions. During his FDR phase, Biden’s definition of COVID-19 stimulus ballooned to encompass much of his Roosevelt-inspired Build Back Better program, meant to put millions of Americans back to work in manufacturing, infrastructure and clean energy while also closing the racial wealth gap, implementing new family leave protections and creating a Public Health Jobs Corps. McConnell is unlikely to accept such an expensive expansion of the federal government. Expect a much narrower bill.

Yet beyond pandemic relief, it’s very difficult — indeed, almost impossible — to envision a new bipartisan era in Washington, as much as Biden might be eager to meet McConnell in the middle. The Senate has more veto power than the House, and the days of Reagan and Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill cutting late-night deals are long gone.

And so Tuesday’s results could force the new president to do what he may loathe most: go it alone. In foreign affairs, that’s par for the course; the president has wide latitude over international relations, an area in which Biden, a former chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, considers himself an expert. His plan is to start rebuilding America’s frayed alliances on day one. “Biden will look at foreign policy as an area where they can really get something done,” said his former aide.

In domestic policy, it’s not that simple, and he may need to fall back on the kinds of executive orders that have become increasingly common in this era of give-no-quarter politics.

So far, mainstream Democrats seem less concerned with process than results. “Biden can deal with COVID and immediately change policy on Paris, immigration and a million other areas,” says Neera Tanden, head of the Center for American Progress, referring to the Paris climate accords, which Trump unilaterally abrogated by executive action. Biden can use the same powers to make the U.S. party to that agreement once more. It may not be the same as a world-altering Green New Deal package, but it is a critical first step in acknowledging the climate crisis.

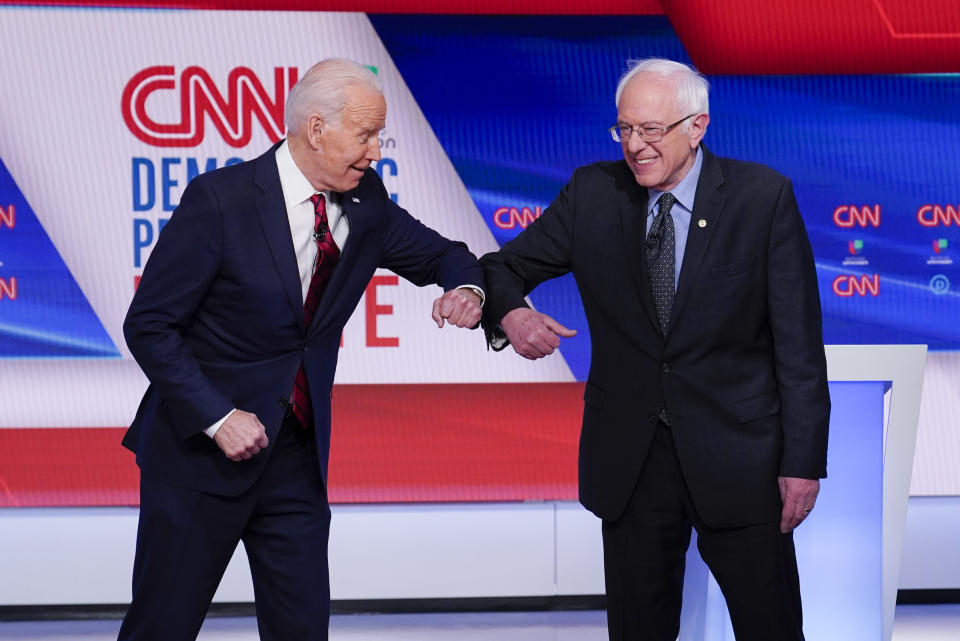

Likewise, the American Prospect, a liberal journal, scoured the policy recommendations issued by a series of unity task forces after the Democratic primary and found 277 actions that the incoming president could unilaterally take to achieve the long-sought goals of the left, including 48 rollbacks of Trump-era policy changes and 78 reforms on immigration, 54 on climate change and 54 on the economy. Spurred by Sen. Bernie Sanders, the progressive stalwart, Biden incorporated many of these proposals into his own platform in July.

“On their own, none of these 277 policies will fully solve any of the interlinked crises we now face,” Max Moran wrote in the Prospect. “But they can go a significant way toward immediate harm reduction. Some can even solve long-standing problems, simply by enforcing or fully implementing laws already on the books. Perhaps most important, all of these policies are ideas that leaders in the moderate and progressive wings of the party broadly agree on, and that Biden should have no excuse not to enact, save for his own policy preferences. There is no hiding behind Congress on these topics.”

As a result, some true-blue progressives hold out hope for what Biden can accomplish in a Washington perpetually described as “bitterly divided.”

Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, said that Biden’s top priority should be to appoint officials who, while perhaps not mainstays of MSNBC and other left-leaning outlets, are skilled in the “wonky use of power” — the kind of seasoned government operatives who can quickly rebuild the administrative masonry Trump has spent the last four years sledgehammering.

“Joe Biden will have immense power that is already vested in the executive branch, and he can use it to make big moves,” Green told Yahoo News. Those moves do not have to be flashy to be transformative, Green believes. For example, Biden can direct federal agencies to purchase only electric vehicles, sending a clear signal to automakers and consumers. He can also instruct his Department of Justice to defend what remains of the Voting Rights Act and other civil rights legislation that Trump’s attorney general William Barr has left to languish.

Yet there are limits to how much Biden can accomplish through appointments. According to a report in Axios, “Republicans’ likely hold on the Senate is forcing Joe Biden’s transition team to consider limiting its prospective Cabinet nominees to those who Mitch McConnell can live with” — i.e., centrist nominees rather than “radical progressives,” as a person close to the majority leader put it, or figures who are controversial with conservatives. Progressive champions such as Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren or rising Georgia star Stacey Abrams won’t make the cut.

“It’s going to be armed camps,” the McConnell source told Axios. As for lower court and Supreme Court nominees, McConnell’s past behavior — defying all precedent by blocking Obama’s final pick eight months before Election Day, then approving Trump nominee Amy Coney Barrett in the closing weeks of the 2020 campaign — suggests that he could block Biden from filling some, most or even all vacancies that arise, depending on which option he deems in the GOP’s best interest.

On that note, another brake on much of Biden’s agenda will be the federal judiciary, which Trump has utterly remade. While the nation has obsessed over the latest Supreme Court drama, Trump has also installed more than 200 conservative ideologues on federal appellate and district courts, where the overwhelming majority — more than nine out of 10 — of legal challenges begin and end.

Those courts are now stocked with young conservatives for whom, say, a big government purchase of electrical vehicles may represent a philosophical affront.

“It’s the lower courts where Trump has made a more dramatic impact,” said Joshua Geltzer, a Georgetown legal scholar who served as a National Security Council attorney during the Obama administration. In those lower courts, Geltzer said, Trump appointed judges other Republican presidents might have passed over because of their radical views.

The judges have uniformly averred that they won’t engage in politics, but it’s hard to imagine an abortion-related decision not having a political outcome. “They have judicial ideologies, but where those lead can create or constrain political space,” Geltzer explained. Just as McConnell’s mere existence as majority leader will preemptively shrink Biden’s range of legislative possibilities, Trump’s judges will give Biden “even less space” to maneuver.

“It changes what policy options are available to the political branches,” Geltzer said.

For their part, pessimistic Democrats on Capitol Hill are already preparing for total obstruction. “Mitch McConnell will force Joe Biden to negotiate every single Cabinet secretary, every single district court judge, every single U.S. attorney with him,” Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., recently told Politico. “My guess is we’ll have a constitutional crisis pretty immediately.”

In his Warm Springs speech, Biden described the way forward as “a way of restoration, of resilience, of healing” — his usual gauzy message of unity, now reframed as a throwback to FDR.

“In his last hours, President Roosevelt was at work on a speech to be delivered the next day. In it he was to say, ‘Today, we must cultivate the science of human relationships, the ability of all people, of all kinds, to live together and work together in the same world at peace,’” Biden said. “‘To live together and work together.’ That’s how I see America. That’s how I see the presidency. And that’s how I see the future.”

It was a moving soliloquy, and it’s likely that Biden, just by being Biden, can mend at least some of the lingering social wounds of Trump’s time in office. But when FDR was sworn in, so were 101 new Democratic congressmen and 12 new Democratic senators — enough, eventually, for a 60-seat majority. Without that, Roosevelt’s fireside chats wouldn’t have amounted to much.

Not that fireside chats play on Facebook. What plays instead in today’s viral, choose-your-own-reality psychosphere is the red meat Trump has served up as president, and will probably continue to serve up, in defiance of the job’s decorous norms, as an ex-president: controversy, negativity, resentment and division, regardless of whether they have any foundation in fact.

“Trump will not feel bound by any rules,” former Trump campaign adviser Sam Nunberg told Yahoo News in 2019. “And he will want to remain relevant.”

For Trump, that is likely to mean he will continue to rationalize his loss by impugning Biden’s win — seeking, in effect, to salve his fragile ego by destroying trust in U.S. democracy.

Needless to say, Biden may find it harder to persuade the 70 million Americans who just voted for Trump to “live together and work together in the same world at peace” when Trump himself is using his enormous post-presidential platform to delude those same voters into rejecting Biden’s entire presidency and the election that produced it. As a result, Republican media and politicians may feel compelled to cater to their delusion — to actually treat Biden as illegitimate.

Perhaps these passions will cool. Perhaps the many grave legal and financial threats dogging Trump will diminish his ability to hog America’s attention. Regardless, the clock is ticking. A president is at the height of his powers the day he takes office. When his first midterm election arrives about 650 days later, he typically loses an average of 30 seats in the House and Senate. Whatever chances he once had of changing the country typically go with them.

With additional reporting by Hunter Walker

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: