How Trump fumbled the coronavirus crisis and sabotaged his own reelection

WASHINGTON — President Trump delivered 2020’s State of the Union address on Feb. 4. It was a triumphant, blustery message that would serve as a preview of his reelection campaign. “Our borders are secure,” Trump said. “Our families are flourishing. Our values are renewed. Our pride is restored.”

Nine months later, that message would seem like a dispatch from a distant planet. The coronavirus was coming that winter; by the time spring came, it would remake everything about the 2020 presidential race, from how Americans cast ballots to which anxieties animated their choice for president.

Exit polls from election night indicate that Republicans and Democrats alike for the most part considered the coronavirus issue to be an important factor in the decision they made.

Republicans’ top concern was the economy, but it is impossible to separate worry about the current economic situation from the pandemic, which has led to the loss of millions of jobs and the closure of countless businesses small and large. Without the pandemic, it is possible the economy would have proceeded on the trajectory it had been on for the last few years. As things stand today, however, the issue is inextricable from that of the coronavirus.

The pandemic was the “single most important issue facing the electorate, the one most responsible for the recession, the [disruptions] of our educational system and the disruption of our sports and entertainment life,” veteran Republican pollster Whit Ayres told Yahoo News.

Trump argued throughout the campaign that his Democratic rival, Joe Biden, would be obeisant to public health officials whom the president depicted as overly concerned with the pathogen. “He’ll listen to the scientists,” Trump said of the former vice president in late October. It was intended as a warning.

“Biden will ONLY listen to the PRO-LOCKDOWN crowd,” his campaign tweeted several days later. “He will SHUT DOWN our economy!”

In selecting Biden, voters have expressed a complex combination of imperatives that will occupy pollsters, pundits and political scientists for months if not years to come. The votes of 161 million people can never be distilled to a single issue, a single desire. Yet it is also clear that Americans rejected Trump’s haphazard, inattentive handling of the crisis. Much as they are exhausted by public health measures, much as they dread another round of lockdowns, they put their faith in a man who has promised a clear and consistent strategy to defeat the disease.

In an unprecedented move, ordinarily staid scientific journals offered ringing endorsements of Biden. The editors of Nature called Trump’s response to the virus “disastrous,” and while that may not have mattered much in the suburbs of Cleveland or the exurbs of Atlanta, it did contribute to the notion that when it came to a once-in-a-lifetime crisis, Trump was simply not up to the job.

None of that was evident on Feb. 4, but the narrative was already shifting, slipping away from Trump. The president did not, or could not, see it.

The day before, his Democratic rivals had participated in chaotic caucuses in Iowa that had been marred by technological mishaps. The winner turned out to be Pete Buttigieg, the boy wonder of South Bend, Ind. As for the former U.S. senator from Delaware, a centrist increasingly lonely in a party moving left, fast? Biden finished fourth.

The coronavirus did receive a mention in the president’s State of the Union address, albeit a very brief one: “We are coordinating with the Chinese government and working closely together on the coronavirus outbreak in China,” the president said. “My administration will take all necessary steps to safeguard our citizens from this threat.”

He sounded confident. The virus was a passing concern at best.

He was also wrong, grievously so.

There were plenty of opportunities in the nine months between Feb. 4 and Nov. 3 for Trump to recognize the seriousness of the pandemic, to convey that seriousness to the American people. He took none of them, in what would prove a series of tragic ironies: elected as an unorthodox truth teller, he tried to spin the coronavirus out of existence as if it were just another aggrieved contractor from his Manhattan real estate days. Fond of depicting himself as a steely decision maker, he routinely made it seem as if he were held captive by his own administration, frequently resorting to undermining officials he employed.

If the Trump presidency was marked by errors in judgment — strange overtures to foreign dictators, political appointments that deviated wildly from his populist promise — none would be as costly to him or the American people than the conviction that the coronavirus was not an enemy to be taken seriously.

Within mere weeks of his Feb. 4 denunciation of socialism, the coronavirus would become the main story in the United States and the world at large. The spring would be marked by lockdowns, nervous shoppers frantically searching for toilet paper and hand sanitizer. Millions lost jobs, then millions more. And through it all, the man who had run as the capable corporate executive willingly — and inexplicably — relegated himself to the role of “cheerleader” (his own word), a sideline enthusiast who often discussed the nation’s response to the pandemic as if he were a cable news host, not the man in charge.

Raised on Norman Vincent Peale’s gospel of “positive thinking,” he could not admit to the obvious reality of the pandemic, because doing so would pierce the armor of machismo that constituted his allure. Later, he would depict face masks as weakness, facts as the luxury of coddled elites.

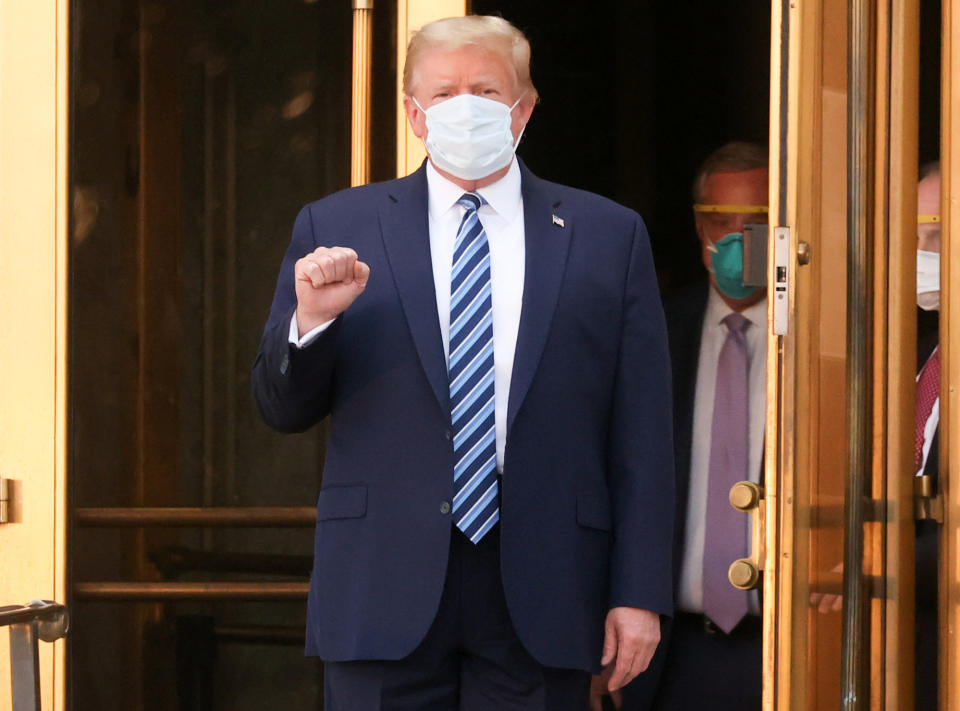

“Don’t be afraid of Covid,” he tweeted after contracting the disease himself — and receiving the best care imaginable at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center outside Washington, which led to a relatively speedy recovery for the president. He did not seem to grasp that ordinary Americans did not have the same access to cutting-edge treatments, and they were not attended to by a team of first-rate doctors. He had gotten over the disease, and he believed the rest of the country should too.

Thirty thousand Americans have died in the month that has passed since Trump’s urging to not fear the disease.

Back in February, none of this could have been imaginable: not the overcrowded hospitals nor the lockdown protests. Cities left hauntingly empty, weddings and funerals conducted over Zoom, angry confrontations over face masks: all this was the stuff of Hollywood fantasy, not what awaited America in 2020.

The story Trump wanted to tell was of an economic powerhouse that would obliterate the measly pathogen from China. “The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA,” he tweeted on Feb. 24, as the window to mitigate the spread of the virus was rapidly closing.

That same day, an article in Journal of the American Medical Association written by Chinese scientists described the “sheer speed” with which the virus had spread in that nation.

No candidate could have expected a global pandemic or predicted its impact on the electorate (though the Obama administration did worry about, and prepare for, a pandemic, as his onetime vice president would remind us). And while presidential elections are often a referendum on a sitting president, the 2020 election was specifically a referendum on Trump’s handling of the crisis. That has served him poorly, even as he has tried time and again to both minimize the impact of the virus and claim that his response to the pandemic has been exemplary.

Americans have been consistently critical of both assertions. A poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted in September, as many people prepared to vote early, found that among registered voters, the coronavirus was the second-most-pressing issue, after the economy.

Other polls have shown that the majority of Americans (about 67 percent) worry about getting infected, while only 40 percent approve of how Trump has responded to the pandemic. Those would prove disastrous numbers on Election Day.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Trump’s coronavirus strategy is how little it changed since his triumphant State of the Union address nine months ago. To this day, he continues to insist that the virus is not a serious threat to most Americans, that wearing face masks is not necessary and that the nation is about to “round the corner,” even as members of the White House coronavirus task force warn that a dangerous new phase of the pandemic lies ahead.

“It’s a slaughter,” epidemiologist Peter Hotez told Yahoo News last week.

Never one for shows of empathy or compassion — he considers the display of such emotions a failing — Trump rarely mentions the quarter-million Americans who have died from COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the coronavirus. He has said those numbers are inflated, and that doctors profit from reporting patients as having died from the coronavirus. Both of those accusations are grossly untrue.

Trump is hardly the only elected official to have downplayed the coronavirus. Democrats and Republicans alike made errors in their handling of the virus, which was entirely new to the world at large when it appeared in the Chinese city of Wuhan in late 2019. Public health officials in the United States told people not to wear masks before reversing course and advising for universal mask usage. The World Health Organization (WHO) initially suggested that the virus is not airborne, when airborne transmission actually accounts for the vast majority of infections.

These and other mistakes of judgment enjoy frequent mention from the president. He reminds the public that Biden accused him of xenophobia for restricting travel from China, a move that probably did slow the spread of the virus to a degree.

Trump’s most fervent supporters may revel in such grievances. But those outside his loyal base have come to largely recognize that as the leader of the free world, he had a unique responsibility to take command in the crisis. That responsibility is one he has raced for months to avoid, seeing the pandemic not as a genuine threat to public health but as a manufactured narrative deployed to destroy his presidency. Ironically, confronting the challenges of the pandemic squarely might have been his best path to reelection.

Instead, he ended his campaign — and his presidency — by asking Americans to believe that the pandemic is not real. “You know, all they want to talk about is COVID,” he said in Pennsylvania. “The Fake News Media is riding COVID, COVID, COVID, all the way to the Election,” he complained on Twitter.

Between the arrival of the coronavirus in the United States sometime in January and its full-blown emergence in March, Trump had plenty of opportunities to implement the kind of response the world may have expected of a nation that practically invented modern-day epidemiology. That would have required listening to experts, something that Trump has never been fond of doing. Instead, he took the counsel of political aides whose main quality was unflagging loyalty to the president. They amplified his most destructive instincts, drowning out wiser counsel that could have steered Trump — and the nation — into less treacherous waters.

Those aides effectively committed Trump to a view that would damage his prospects at reelection. Speaking on Feb. 28 at the Conservative Political Action Conference in National Harbor, Md., then-acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney — an abrasive former congressman from South Carolina — set out what would become the unofficial presidential line on the coronavirus.

“The reason you’re seeing so much attention to it today is that they think this is going to be the thing that brings down the president. That’s what this is all about,” Mulvaney said. He proceeded to compare the coronavirus to the common flu, much as the president would in the coming months, in a failed attempt to convince Americans that COVID-19 would amount to little more than a seasonal inconvenience.

Days after Mulvaney spoke, news broke that several attendees at the conference had been infected with the coronavirus. Many supporters of the president dismissed that outbreak as a minor affair, but a few saw something more ominous, a warning to be desperately heeded. “For the thousands who attended CPAC, they communicated what was essentially fake news, giving the impression that everything was fine, when there is no way they could have known,” said Raheem Kassam, a conservative writer who had long been a defender of Trump.

Trump could have taken the CPAC outbreak — which was minuscule, considering what followed — as a sign of things to come, of what the virus could do to his triumphalist narrative of American greatness restored. He did the exact opposite, continuing to shrug off the virus even as it spread through the Seattle area and parts of California.

“You have to be calm,” he said on March 6. “It’ll go away.” The notion that such false assurances could cost lives never seemed to occur to him. Instead, he tried to talk his way out of the problem, as he had done so many times in his private life as a businessman. He had tweeted, shouted, heckled, interrupted, mocked, lamented and filibustered his way through crisis after crisis in the White House. This would be no different.

Americans of all political persuasions understood that the situation was more serious than Trump let on. Life began to change in ways large and small. The next day, March 7, retail giant Costco announced that it would no longer give out free samples at its stores. “Okay, now this #CoronaVirus has officially gone too far,” a radio host named Kevin Begley tweeted. “Make that vaccine already.”

Four days later, the WHO upgraded the coronavirus to a pandemic. Trump continued to press his own case, unfazed. “It’s going away,” he said that same day. “We want it to go away with very, very few deaths.”

On March 12, Mike DeWine, the Republican governor of Ohio, shut the state’s schools, becoming the first in the nation to do so. Eight days later, Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York, a Democrat, implemented a stay-at-home order as New York City emerged as a coronavirus hot spot.

Much as he may have wanted as few deaths as possible, Trump never took the steps that would make that a reality.

The ranks of experts within the federal government had been thinned out, many top scientists, policymakers and experts driven out by Trump political appointees intent on ferreting out adherents of a fictitious “deep state.”

It did not help that Trump showed little attention to any issues other than those that motivated his core supporters. He wanted to spend the spring campaigning, holding large rallies as Democrats continued their nasty internecine primary fight. But the coronavirus would make that impossible, forcing him into a battle he did not have the fortitude to wage.

His last spring rally took place in Charlotte, N.C., on March 2. He acknowledged the coronavirus, but only to dismiss it. “The United States is, right now, ranked by far No. 1 in the world for preparedness,” he told his boisterous audience.

And this was true, according to a Johns Hopkins University assessment. But the rankings also presumed that that preparedness would be marshaled in a time of crisis, not merely touted as a static fact. It was supposed to be a starting point, not a talking point.

“A lot of good things are happening,” Trump told his Charlotte fans.

After Trump returned to Washington from North Carolina, he would not hold another campaign rally for nearly four months. By that time, both he and the rest of America would be living in a different world.

That period from March to June would mark the most consequential stretch of Trump’s presidency. It was the crisis many had feared would come, only to find Trump entirely unprepared. For three years he had reveled in the showmanship of the office, without taking much interest in the work the office required. Nor had he shown the kind of patience or attention to detail that would be needed to battle what he deemed an “invisible enemy.”

Still, there was some hope — at least at first — when Trump began to hold daily coronavirus briefings, top administration officials arrayed glumly behind him. Impeachment was a distant memory. He seemed to endorse the guidance of his two top coronavirus advisers, Drs. Deborah Birx and Anthony Fauci. “I’m glad to see that you’re practicing social distancing. That looks very nice,” he told the reporters gathered before him on March 16. “It’s very good.”

For the first time, the president seemed genuinely, viscerally aware that a crisis was at hand, treating the briefings with a solemnity that had simply not been part of his repertoire for the previous three years. Observers noted, and hardened critics suddenly lavished him with praise. “This was remarkable,” said Dana Bash of CNN on March 17. “He is being the kind of leader that people need, at least in tone,” she went on to say, “that people need and want and yearn for in times of crisis and uncertainty.”

Americans appeared to agree, even if the tone did not usher in a radically new approach. States were still competing for personal protective and hospital equipment. Testing remained perilously difficult to come by.

In late March, Trump signed into law a $2 trillion relief package intended to help small businesses, families and corporations. This may have been perilously close to the kind of socialism that he had been denouncing, but nobody seemed to mind. The president saw his approval rating rise to nearly 46 percent, the highest it had been since the very first days of his administration. Meanwhile, his disapproval rating dipped just below 50 percent, a first since March 2017.

But by that time, Trump had already discarded the mantle of solemnity he had donned earlier that month. The kind of attention he has always sought required conflict as its oxygen. And so the coronavirus briefings quickly reverted to Trumpian form, with the president feuding with reporter Peter Alexander (“You’re a terrible reporter”) and the Democratic governor of Michigan, along with the Republican governor of Maryland.

Here was the Trump the nation had come to know. Here he was as he had always been, personal and petty, settling scores instead of setting the nation on a course out of the pandemic.

Aides to the president were already worried about the briefings before April 23, when their worst fears played out on live television. On that day, Trump mused about shining “light inside the body” to kill the coronavirus. He also suggested that people could drink disinfectant. “You see, it gets in the lungs, and it does a tremendous number on the lungs,” Trump said, as a horrified Dr. Birx watched.

That reaction, shared endlessly on social media, became a kind of withering exit music to Trump’s brief attempt to act like an ordinary president. After bleach, there could be no way back.

The briefings ended after that, replaced by celebratory statements from the president that were simply not occasioned by reality. “We have met the moment, and we have prevailed,” Trump said on May 11 from the Rose Garden. He was impatient for the economy to open, for his rallies to resume. That required him to downplay a virus that had killed 80,000 Americans by that time and would kill many more in the months to come.

At the same time, the perennial pitchman hyped the nation’s response, inflating incremental victories into game changers. “AMERICA LEADS THE WORLD IN TESTING,” said a banner hung outside the Oval Office as Trump spoke that day. Testing had been getting easier to find but was hardly where it needed to be for any congratulatory backslapping to begin.

The summer would be marked by two competing crosscurrents: Trump insisting that the virus was defeated and the virus issuing constant reminders that it was not only alive but very much winning. It did so by tearing through Sun Belt states including Florida, Arizona and Texas, which had been the quickest to reopen.

Even as thousands began to die there, Trump praised those states for reopening their economies while lambasting Northeastern governors, often but not always Democrats, who were proceeding more cautiously. “I hope that the lockdown governors — I don’t know why they continue to lock down,” the president lamented on June 5.

This would be his position throughout the summer, hectoring Democrats to reopen while praising Republicans who did so, even as it became clear that governors like Ron DeSantis of Florida — as zealous a supporter of Trump as there exists on the national scene — were not only badly mishandling the virus but, to make matters even worse, flagrantly misrepresenting just how devastating the disease was turning out to be in their states.

Trump did return to campaigning on June 20, with a rally in Tulsa, Okla., that was nothing like the packed, galvanizing affairs of 2016. Among the attendees was Herman Cain, the businessman who’d once sought the Republican nomination for the presidency. Cain caught the coronavirus and died several weeks later, after a prolonged hospitalization. He was 74 years old. So was Trump.

Still, there would be no rallies until late August, depriving Trump of the crowds that are the oxygen of his political movement. In late July he resumed coronavirus briefings, and it briefly seemed like the sober Trump some had glimpsed in March was back. The outbreak across the Sun Belt appeared to have chastened him, and he offered an uncharacteristically pessimistic — and just as uncharacteristically accurate — view of the situation.

“Some areas of our country are doing very well; others are doing less well,” he said at the July 21 press briefing. “It will probably, unfortunately, get worse before it gets better — something I don’t like saying about things, but that’s the way it is.”

As would be the case throughout the pandemic, Trump efficiently sabotaged himself and his administration’s response by continuing to question the efficacy of masks, maligning mitigation measures and feuding with both Democratic officials and scientists who answered directly to him.

“With the exception of New York & a few other locations, we’ve done MUCH better than most other Countries in dealing with the China Virus,” the president tweeted on Aug. 3, deploying the deeply partisan attacks some of his advisers implored him to leave behind, even as other loyalists encouraged the combative attitude, arguing that Republican voters would reward him for it come November.

“Many of these countries are now having a major second wave,” the tweet continued. “The Fake News is working overtime to make the USA (& me) look as bad as possible!”

If the spring had been about trying to seriously handle the pandemic, and summer about reopening, then the fall brought a new phase, with the arrival of Dr. Scott Atlas, a Stanford neuroradiologist of conservative political leanings who argued for a herd immunity approach to the virus, which would allow for a somewhat controlled spread through the population.

With his disregard for facts and boundless self-confidence, Atlas quickly brought Trump under his thrall. Inattention to the virus was now the official White House strategy. Everything that could be done had been done. This point was made with stunning forthrightness by White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, who essentially told CNN’s Jake Tapper that when it came to the coronavirus, the Trump administration had no weapons left in its arsenal.

“We are not going to control the pandemic,” Meadows said, in comments that instantly went viral and were predictably seized upon as evidence of surrender.

Trump’s own weariness with the virus increased sharply after his own hospitalization with COVID-19 in early October. Some thought the experience would chasten him. Such hopes never had much purchase on reality. Trump emerged as Trump.

The president’s closing argument in the last two months of the campaign was that while he wanted to reopen the nation, Biden would keep the nation locked down for an indefinite period. Schools would be closed. The lights of restaurants would remain dark.

Trump used his own recovery from the coronavirus as evidence that there was nothing to fear. His rallies resumed, with crowds at one chanting that he was an invincible “Superman.” Few attendees wore masks or practiced social distancing. The president’s resurrection became a kind of closing argument, one that had traction with a conservative base that had come to regard Trump with a spiritual affinity that ordinary politicians do not enjoy.

In the last several days of the campaign, Trump took to the trail with an almost inhuman energy, his relentless schedule of huge rallies a counterargument to Biden’s (intentionally) sparse and sparsely attended events. Trump was implicitly asking Americans which reality they wanted to occupy: one in which you constantly worried about 6-foot distances and aerosolized viral particles or the one you had experienced before the coronavirus came along.

The narrowness of Biden’s victory suggests that more people were persuaded by Trump’s argument than most pollsters and pundits had supposed. That was especially true in areas hard-hit by the coronavirus, where one might have expected Trump’s message to have less traction. The opposite proved true, for reasons that remain hard to decipher.

“President Trump won’t have to recover from COVID,” Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla., an avid Trumpist, tweeted in early October. “COVID will have to recover from President Trump.” Mocked as that message was, it provided an insight into Trump’s final pitch to voters, a show of energy and force that he hoped would be contrasted with Biden’s good-government cautiousness, a cautiousness Trump said was no longer necessary and was in fact destructive.

Polls showed that he was down, and down badly. Establishment Republicans pleaded with him to make a last-minute reversal, to finally confront the coronavirus with the statesmanship it deserved. He could save the nation and his own political prospects in one fell swoop.

Trump instead continued to insist that the coronavirus was a conspiracy deployed to damage his election night prospects. “We’re rounding the turn. You know, all they want to talk about is COVID. By the way, on Nov. 4, you won’t be hearing so much about it. ‘COVID, COVID, COVID, COVID,’” he said at a campaign rally on Oct. 26 in Allentown, Pa.

In fact, in the days since last Tuesday’s election, the nation has set several records for new daily infections.

Trump told supporters at a rally that doctors were manipulating coronavirus statistics for their own benefit. That was in Waterford Township, Mich., on the last day of October.

There would follow, in the final hours before the election, rallies in Dubuque, Iowa; Hickory, N.C.; Rome, Ga.; Opa-locka, Fla.; Fayetteville, N.C.; Scranton, Pa.; Traverse City, Mich.; Kenosha, Wis.; and Grand Rapids, Mich.

The rallies almost certainly caused the coronavirus to further spread. It did not matter to the man who held them or to the men and women who came to them, sometimes from hundreds of miles away. The rallies went late into the night, so that his beloved primetime Fox News anchors awkwardly cut between their own programming and the seemingly unending Trump show.

“Look at him,” Fox News host Laura Ingraham said one evening, as he barnstormed through the Midwest with a defiance that he hoped would convince voters that the coronavirus was over, and so were their months of donning masks and helping children with Zoom lessons. “He’s still going.”

He may well keep going, doing his own thing, but he is likely to find that the majority of Americans are moving on. President-elect Biden announced his coronavirus task force on Monday.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: