Can humans see ultraviolet light?

The colors of the rainbow are all around us, but so are hues that most of us can't see, including ultraviolet — a wavelength that eludes many humans but, surprisingly, many animals can perceive.

Ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths are smaller than those on the visible spectrum, but can people see them? The answer, it turns out, depends on how old you are and whether your eyes contain UV-filtering lenses, experts told Live Science.

First, it's important to understand how sight works. In the back of the eye, the retina has photoreceptors that sense light and send signals about the wavelengths they detect through the optic nerve to the brain, which interprets them as color.

In fact, our blue-detecting cones can detect some UV light. However, the lens — the clear, curved structure in the eye that focuses light onto the retina to help us see more clearly — filters out UV light, so the high-energy wavelength never actually reaches the cones, Michael Bok, a biologist who studies vision at Lund University in Sweden, told Live Science.

Related: Why doesn't your vision 'go dark' when you blink?

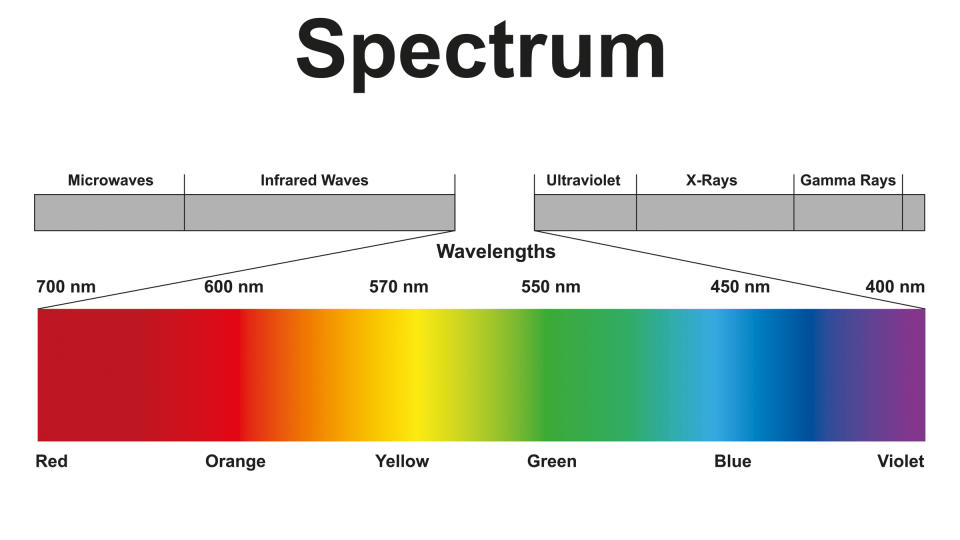

Or at least the lens filters out most UV wavelengths, for most people. Despite the lens' ability to filter out most UV light — to protect our eyes from UV damage, which can age structures in the eye and increase the risk of cancer — most young people can perceive some amount of it. In a small 2018 study published in the journal PLOS One, all of the college-aged participants at the University of Georgia could see UV light at approximately 315 nanometers. (The full range of UV light is about 10 to 380 nm, with violet beginning at the latter.) During the experiment, "our subjects consistently reported that the light appeared a desaturated violet-blue," the researchers wrote in the study. But this ability appears to drop off around age 30, indicating that aging reduces the ability to see UV wavelengths.

Some people can see much more of the UV light spectrum, however. Up until the 1980s, cataract surgery involved removing the cloudy lens from the eye and not implanting a replacement, so people who had the operation could see UV light. For these people and those born without a lens, UV light looks like a pale blue or pale violet, Bok said. In a famous example, impressionist painter Claude Monet saw more blue and purple overtones in water lilies after having cataract surgery in 1923 and reflected this difference in his later paintings.

But while most adults can't see UV light, that's not the case in the animal world. Many mammals — including dogs, cats, ferrets and reindeer — can see some UV wavelengths throughout their lifetimes, according to a 2014 study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The study also noted that the ability to see UV light is widespread in invertebrates, fish, birds, reptiles and amphibians, which often have cones specifically for detecting UV light — and lenses that let it through.

So why can so many animals see in the UV range? "For any color vision, the utility is to be able to improve contrast for detecting objects or important things in your surroundings," Bok explained.

related mysteries

—How do our eyes move in perfect synchrony?

—Why do babies rub their eyes when they're tired?

—Can carrots give you night vision?

There are many ways UV helps animals do this. For example, many predatory sea creatures use UV light to help see the silhouettes of prey, like plankton and fish larvae, because there's a lot of UV light in shallow water, said Thomas Cronin, a biologist who studies visual ecology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Many insects use this type of vision to sense patterns on flowers, and some use polarized UV light in the sky to help them navigate. Many birds signal to each other via their plumage in colors in the UV range and use it to find ripe berries.

"The more we look into it, the more it seems quite clear that it's pretty common," Bok added.

In fact, the ancestor of vertebrates could see UV light and had a photoreceptor specifically for it, according to a 2003 study in the journal PNAS. But somewhere in humans' evolutionary history, that photoreceptor shifted more toward detecting violet than ultraviolet wavelengths. Perhaps we couldn't afford the damage to our eyes because we are a long-lived species, or maybe it was because UV light comes at the cost of blurrier vision, Cronin said.