The inside story of Memphis's Confederate monument heist

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — The statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the Confederacy’s favorite sons, stood in Forrest Park in Memphis, overlooking the busy thoroughfare of Union Avenue for over a century. The bronze monument to Forrest — cast in Paris at a cost of nearly $33,000 and weighing 9,500 pounds — was dedicated with great fanfare in his adopted hometown in 1905. Joining the statue were the remains of Forrest and his wife, which had been moved from a local cemetery. For the white aristocracy of Memphis who had raised the funds for his installation, it was a banner day.

But Forrest was not just a Confederate general revered for his equestrian skill and battlefield acumen. Before the Civil War, Forrest was a slave trader, making his fortune running the Negro Mart on Adams Street, which sold “the best selected assortment of field hands, house slaves and mechanics,” according to an old newspaper ad. During the war, he was one of the South’s most celebrated soldiers but also was accused of leading a massacre of Union troops, including many freed slaves, who had surrendered at Fort Pillow, in Tennessee. “The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down,” said one Confederate sergeant of the attack. Forrest, however, noted in his post-battle report that he hoped the incident would remind the Union that “negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.” (The extent of Forrest’s responsibility for the brutality is still debated.) After the war, Forrest was chosen as the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, leading the organization in the aftermath of the Confederacy’s defeat.

His statue’s presence was perceived as a daily affront by the majority African-American city that was at the center of the civil rights movement. In 2017, a movement to remove the statue that had been frustrated for years found fresh momentum under new leaders, and City Hall worked legal channels to circumvent a restrictive state law. To get around the Tennessee Legislature, city officials quietly crafted a plan to rid the city of the monument, a creative ploy that ironically echoed the Southern resistance to civil rights laws decades ago. On a chilly evening just before Christmas, the legal statue heist went down, and in front of a small, hastily assembled crowd, Forrest fell, ending a painful chapter in Memphis history. From the accounts of over a dozen of those involved with the process, this is how it happened.

In 2015, after the slaying of nine people at a historic black church in Charleston, S.C., a revolt against Confederate symbolism began to sweep across the country. South Carolina stopped flying the Confederacy’s battle flag above its state Capitol, and statues honoring the secessionist movement and its heroes began to fall, often under the cover of darkness in attempts to limit the impact of protesters who sympathized with the iconography. Although officials in most cities had the power to make decisions on the statues, any attempts by Memphis to follow suit were blocked by the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act. Passed in 2013 and modified in subsequent years by the heavily Republican state Legislature, the law prevented local municipalities from removing memorials on public property without applying for a waiver through a complicated process that would likely end with rejection by the state’s Historical Commission, whose members were appointed by the Republican governor.

The statue’s early existence was relatively uncontroversial, except for a dispute over which direction it should face (some said Forrest facing south made it seem like he was in retreat from the Union; others said he should be looking upon his homeland; the sculptor said he should be facing where he’d get the most sun) and complaints that oxidation had turned the general green. Then vandalism began in the 1960s, with Forrest’s saber being broken off repeatedly and eventually included spray paint marking the base with “KKK,” “slave trader” and “racist murderer” in 1994. Memphis parks were segregated until the Supreme Court ordered them desegregated in 1963. A year later, a statue of former Confederate President Jefferson Davis went up a mile and a half away, joining other likenesses around the country as Congress passed the Civil Rights Act.

“My father grew up in Jim Crow-segregated Memphis, and he could not walk through that park unless accompanied by a white person and he could not sit down in the park as an African-American,” said Shelby County Commissioner Van Turner.

“I never understood as a kid growing up these are public parks yet they display a monument of someone that was brutal to my ancestors,” said City Council Chairman Berlin Boyd. “He sold them, and he was not the type of image or man we should be portraying, especially in a city like Memphis that is predominantly African-American.”

“We could not go in that park and do what other citizens were able to do because of segregation,” said the Rev. Lasimba Gray, 71, also a Memphis native.

There were petitions against the statues from civil rights groups in the 1970s and 1980s, but they never posed a serious threat. Gray and Shelby County Commissioner Walter Bailey, 77, renewed the push to remove the statues and rename the parks in 2005. Gray invited the Rev. Al Sharpton to lead a rally in support of the movement, but gained little traction with elected officials. Even some in the African-American community regarded the group, as Gray tells it, as “troublemakers.”

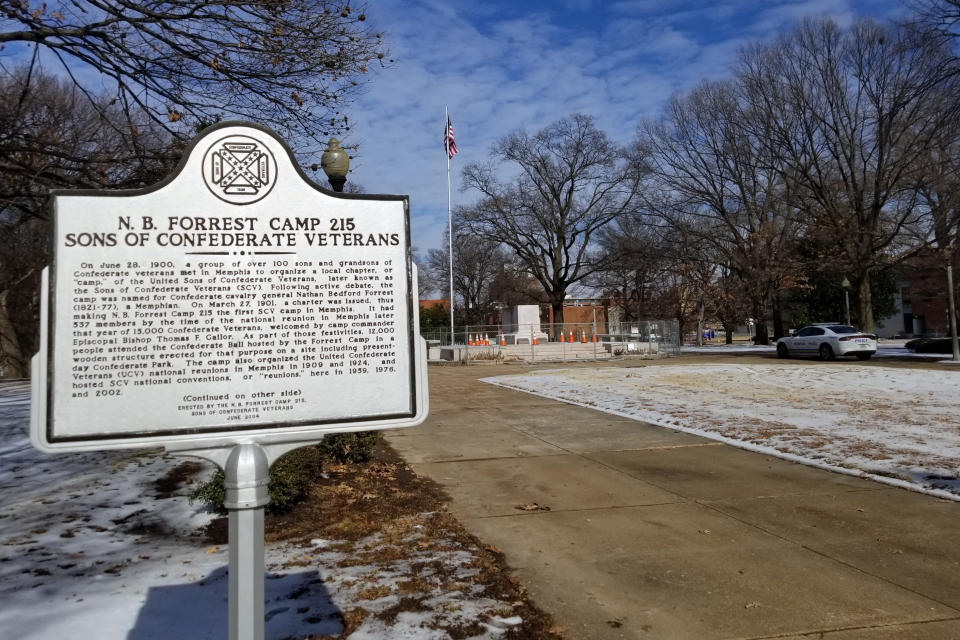

The legal wrangling from both sides picked up in 2013. Just before the Heritage Protection Act was passed by the state Legislature, the City Council voted to rename the parks — Forrest’s became “Health Sciences Park” — a move that sparked a Klan rally in town. The issue arose again in 2015 after the killings in Charleston, S.C. The City Council voted to take down the Forrest statue but was blocked under the Heritage Protection Act.

Enter Tami Sawyer and Mayor Jim Strickland. Sawyer is a local activist who, in May 2017, founded a group dedicated to the removal of the monuments: Take ’Em Down 901, a reference to the city’s area code. Strickland is the city’s first white mayor in 25 years, a Democratic city councilman who won election in 2015. Sawyer collected signatures for a petition and pressured City Hall, organizing rallies and presenting thousands of names in support of the removal of the monument that she referred to as a “source of oppression and hatred in Memphis.” Strickland, who voted to rename the parks and tear down the statues as a City Council member and called the Forrest statue “a monument to Jim Crow” as mayor, had his team begin to look into a method to legally circumvent state law. City Hall and activists were on the same side but did not work in tandem, having what Sawyer called a “sour” relationship. City officials rejected the solution proposed by Take ’Em Down 901 to ignore the law and just pull down the statues. But both parties were instrumental in getting it done.

Things came to a head in August after a rally against the removal of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s statue in Charlottesville, Va., turned to violence. The killing of counter-protester Heather Heyer by a white supremacist inspired rallies organized by Sawyer at the Forrest statue. Seven anti-monument protesters were arrested. As summer ended, the business and religious communities, including the Chamber of Commerce and more than 150 local religious leaders, began calling for removal of the statue. Even Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, a Republican, urged the Historical Commission to consider the waiver that would allow the monuments to come down.

“The events in Charlottesville obviously were tragic, but they also built a lot of public support — you saw this across the country,” said Strickland. “Here we were able to get blacks and whites, Democrats and Republicans, clergy members from conservative congregations and from liberal congregations, the business community all pushing on this.”

Civic leaders set a deadline: The statues had to be down by April 2018. That’s when the city would host MLK50, a series of events commemorating the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination at the Lorraine Motel, a building within walking distance of both monuments and that today houses the National Civil Rights Museum. As a lawyer, Bailey had represented King during the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike, the labor movement that brought King to the city the day of his assassination. That movement started when black sanitation workers attempted to unionize following the deaths of employees killed by malfunctioning equipment. The city, led by a segregationist mayor who refused to meet with black leaders, opposed the strike. “I am a man,” the slogan from that strike, is plastered across the city in promotion of the MLK50 events, printed on banners on light posts and has inspired special uniforms for the NBA’s Memphis Grizzlies.

“I’ve always considered the Memphis effort as being the most important,” said Bailey. “And it’s because Forrest was here. And he was a butcher, no question about it.”

On Oct. 13, city officials and activists made the trek to Athens, Tenn., for a meeting of the Historical Commission. Sawyer and Strickland both spoke, and Strickland thought they had a good chance of prevailing, but the commission voted overwhelmingly against the city.

The city explored other options, including a bill introduced in the Legislature to override the commission’s vote, but time was running short. Strickland, however, had noticed a loophole in the law: The Heritage Act prevented only the alteration of public parks. If the two parks were sold, the new owners could do what they wanted with them, including taking down the monuments.

It would represent a fitting turnabout, as segregationists had used similar tactics in the 1950s and 1960s in response to desegregation orders — selling off public facilities or just refusing to pay for them, while white citizens fled to whites-only country clubs and private schools.

The city began planning for the move even before the commission vote, passing a law in September to allow the government to transfer property to nonprofit entities at a below-market price. After a series of discussions with the city’s chief legal officer, Bruce McMullen, Shelby County Commissioner Turner founded the nonprofit Memphis Greenspace Inc.

The plan could work, but those involved had to keep things quiet. If word got out, there was the risk of an injunction that might have nixed the deal — or attracted demonstrators who could have made the physical removal of the statues difficult or even dangerous. Boyd said that the group that knew was so small that his colleagues on the council were not even aware of the plan’s particulars.

In the wake of the October ruling, the final pieces of the plan were put into place. On Dec. 15, Strickland signed the agreement selling the parks to Turner’s group for $1,000 each, with the requirement that the parks would remain public space and with the deal contingent on council approval. That approval was supposed to come on Dec. 19, but the night’s council meeting required a continuation to Dec. 20 after storms rolled through town that would have made the removal process difficult. The following day, the council voted unanimously to approve an ordinance that would ratify the deal with Greenspace. Boyd signed the agreement before it was rushed upstairs by McMullen to Strickland, who put pen to paper finalizing it. Calls then went out to the waiting police to start establishing perimeters as Turner received official word he was now the owner of two parks.

Sawyer, the leader of Take ‘Em Down 901, had attended the City Council meeting after receiving a call earlier in the day that the vote was likely to happen. When the motion passed, she began texting the news to others, who met her at Health Sciences Park. The mayor’s office began making calls, and across Memphis, people abandoned dinners and cut short Christmas shopping trips to watch history being made. Looking out of his office window, Bailey saw police cars a few blocks from City Hall and assumed a protest was underway. Soon after, he received a call from the mayor’s office inviting him to join a press conference later that evening.

As those in the park began to live-stream the proceedings to social media, the crowd began to grow. Fog rolled in and it began to drizzle, creating a somber and portentous mood. In the mayor’s office, Gray joined the city staff members as they ate pizza and watched the events unfold on television. The initial attempt of the crane to rip the statue from its base just before 9 p.m. had failed. As anxiety rippled through the room that Forrest would, perhaps, be able to hold on, Strickland made the sign of the cross.

At exactly 9:01 p.m., the statue of Forrest atop his horse was finally raised from its base, eliciting cheers as it was slung onto a waiting flatbed. Everyone says the timing, corresponding to the city’s area code and the name of Sawyer’s group, was simply a coincidence or “divine providence,” as Gray put it. Minutes later, the monument was gone, whisked away to a still-undisclosed location for storage. Sawyer was ferried across the police line to the now-empty base by County Commissioner Reginald Milton, who had found out about the removal on the news and rushed down to be present. Milton told Sawyer that she was a part of this and deserved to be in the middle of it.

“It wasn’t when it came off the base,” said Sawyer shortly after the events of that night. “It was when they moved it over that I really began to celebrate because it’s off, it’s over, it’s not going back on.”

The equipment then moved to Memphis Park, and the Jefferson Davis statue was gone shortly thereafter. After years of legislative roadblocks and pushing from activists, the actual removal took only a few hours.

“It is an amazing thing to be standing in the middle of history,” said Milton, who was born and raised in Memphis. “You read about history, you’re told about history, but when you’re standing in the middle of an historical event occurring before your eyes and you know you’re a part of it, it’s moving.”

For Bailey and Gray, the moment was bittersweet. Neither Walter Bailey’s brother D’Army Bailey nor their friend the Rev. Dwight Montgomery lived to see the statues come down. D’Army Bailey was a judge and activist who had been the driving force in the opening of the Civil Rights Museum before his death in 2015. Montgomery was among the religious leaders who signed the petition in support of the statue’s removal; he died in September.

“To live long enough to see those statues taken down is a fulfilling thing for me,” said Gray, who called Strickland his “newest hero” for his efforts.

Even though the monuments are down, the legal struggle is still not over. The Sons of Confederate Veterans has called Greenspace a “sham” nonprofit and filed suit against the city. (McMullen was not concerned about the Sons’ legal action. Turner said the organization was legitimate and planned to not only improve both properties, but also potentially purchase more.) The state Legislature is weighing its options after complaining that the actions of Memphis flouted the spirit of the Heritage Protection Act, potentially violating local sunshine laws. The Historical Commission’s website states that it is also weighing legal options.

The future of the statues is still being decided. Some historical organizations have reached out to Turner about acquiring the monuments, and he hopes to transfer ownership “sooner rather than later.” He also said that they were in discussions with descendants of Forrest about returning his remains to the gravesite at historic Elmwood Cemetery, the location cited in the general’s will as his preferred resting place. An Elmwood representative said that the cemetery had not been contacted about a reinterment but that the original plot was still available, provided someone could find and recover the remains in the park.

But those who worked so hard to take down the monument know it is only a minor victory in their attempt to revive a city that still has a number of pressing issues. Memphis is among the most segregated cities in the country, with high crime and poverty rates and a half century of population loss. But the coordination on removing the Forrest statue has provided some inspiration as the work continues.

“If we were smart enough and strategic enough to beat the state at their own, we should be smart enough and strategic enough to deal with some of the issues we have in our city,” said Boyd.

Read more from Yahoo News: