Insurgent candidate tells Guatemalans: Stay, don’t go to the U.S. This time, they’re listening.

CHIUL, Guatemala ? Life in Bartolo Báten’s village has been defined by corruption: A teacher who can’t get a job at the school until she pays a bribe. A water project that runs out of money before the pipes reached town. Sick residents who can’t afford the medicine that’s available elsewhere.

And so for as long as Báten can remember, they have survived thanks only to the relatives who leave Guatemala for the United States, and the dollars they send home.

Báten’s father worked in the U.S. for three years in Florida, North Carolina and Ohio. His brother still labors in an Ohio factory, one of around 1.1 million Guatemalans working in the U.S.

Even his friends who didn’t go north had to leave their mountain village to find work in Guatemala City. From there, they began pinging on Facebook earlier this year about a man named Bernardo Arévalo. “Look, these are the things Arévalo is proposing,” they told him. “You’ve got to spread this message at home.’”

“I want to stay and make a change,” said Báten, 28.

That idea – which can be heard among crowds flocking to Arévalo’s campaign rallies – makes Arévalo not only the leading candidate in his own country’s presidential race, but a consequential figure in another one 2,000 miles north.

Arévalo, initially an outsider, surged to the front of the race, on a promise to end corruption that has turned generations of Guatemalans into U.S. immigrants.

If Arévalo wins a runoff election Sunday, he stands poised to reshape the Biden administration’s approach to one of its most intractable challenges: the endless flow of migrants to the southern border.

Republican governors have responded with get-tough approaches, snaring border crossers with razor wire or shuffling them onto buses bound for Democratic cities. All that now plays out as the U.S. hurtles toward a possible election rematch between President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump – who ran on the phrase “build the wall.”

While the political debate in the U.S. focuses on border security, no effort is likely to succeed without addressing root causes of poverty, corruption and violence.

The Biden administration in 2021 heralded a plan for hundreds of millions of dollars to address just that. But Central American leaders were reluctant to cooperate.

Arévalo promises he is different.

“The first thing that will happen is that actually the United States will find a partner that is rooting out corruption and will have all intention of actually working toward development,” Arévalo told USA TODAY in an exclusive interview in the capital city of Quiché, the same state where Báten lives.

In the week leading up to the runoff vote, USA TODAY spent three days following Arévalo’s campaign across rural Guatemala in a country where top officials have been sanctioned by the U.S. as “undemocratic actors,” where the World Bank found nearly 20% of the gross domestic product comes from money sent home by Guatemalans in the U.S.

Arévalo’s candidacy stirs memories of an older generation: His father was the country’s first democratically elected president after an oppressive dictatorship. His ideas galvanize a younger generation’s social media idealism on the premise that Guatemalans wouldn’t leave in record numbers if they could find opportunities at home. Arévalo said a shared agenda with the United States is vital. “At the end of the day,” he said, “people are going out of places like Quiché because there are simply no options for them.”

Who is Bernardo Arévalo?

On a warm weekday morning, Báten and his father led a march of dozens of Chiul residents through the cobblestoned streets of Santa Cruz del Quiché.

As the youngest member of Chiul’s council of leaders, Báten rallied to Arévalo’s cause, along with town elders who carried a banner the width of the street and blew noisemakers. They chanted in rhyme: "?Se ve, se siente, Arévalo presidente!" Roughly, "See it, feel it, Arévalo for president!"

“We don’t want any more corrupt politicians,” said Francisco Báten Itzer, Báten’s father. “We don’t want any more malnourished children, no more poverty and injustice. We want someone new.”

Tall, with glasses and a graying goatee, Arévalo has a Ph.D. and speaks five languages but was otherwise unknown to most Guatemalans until a few months ago. His bid was seen less as a real chance to take the presidency and more as an opportunity for a relatively new party, popular among urban academics, to expand its base.

That was until judges aligned with President Alejandro Giammattei eliminated three candidates on alleged violations in the first-round election. Thousands of voters nullified their ballot or opted for last-place Arévalo.

It was a massive, quiet protest against the alleged machinations of a group of powerful elites known in Guatemala as the “pact of the corrupt.”

Arévalo surged to the top, landing a spot in the runoff against Sandra Torres, a firebrand former first lady.

Torres, who declined USA TODAY’s multiple interview requests, has shifted to the right as she makes her third bid for the presidency. She has seized on Arévalo’s birthplace, calling him the “Uruguayan candidate,” even though the constitution allows Guatemalan citizens born elsewhere to run for the office.

Arévalo’s unlikely success, resonant message and down-to-earth campaign through rural communities drove turnout from influential locals like the group from Chiul.

These town leaders can recount how the water pipeline was built to within sight of their village but then stopped, and now, when the rains dry up, so does the water in their faucets. How the wife of one of the men can’t afford basic medicine for a kidney condition, in a country where the public health system has a history of purchasing fraud, bribery and deals that benefited pharmaceutical suppliers, leaving patients at risk.

Báten’s 25-year-old wife, he said, is a trained teacher, the kind his town needs. But she can’t get a teaching job, he said, because officials want her to "purchase" a work contract – a common form of bribery.

Those realities drove the group from Chiul as they marched through Santa Cruz del Quiché toward the campaign rally.

As they did, Arévalo was fielding questions at a news conference on the edge of town. What will he do to entice young people living in rural areas to stay?

“We need to remember that Guatemala is a country in which 6 of every 10 people is a young person and the majority of this population is indigenous,” Arévalo said. Rather than buy votes with gifts of rice or potatoes, he said, “Our plan is to bring universal access to social services, including health care, education and highways. We’re going to focus on the rural areas that have been most abandoned by the government.”

“Our only condition,” he said, “is that we’re going to do it with transparency and honesty.”

Several hundred people filled one side of the central plaza and spilled up the stairs of the Catholic church as Arévalo climbed the stage. The country’s ethnic diversity was on display in the traditional dress of men and women from numerous, distinct Mayan communities.

Community leaders brought gifts. Báten climbed the stage and handed Arévalo a "morral," a woven bag worn by indigenous men in Chiul.

Arévalo promised to build highways, ensure access to water and expand educational opportunities, his voice rising like a preacher’s as he yelled "ya basta," enough with corruption.

Then he paused, and considered the gift Báten had given him.

There is a "morral" hanging by his desk, Arévalo said softly. A bag that was gifted to his father, Juan José Arévalo, when he was campaigning in 1944.

“I’m going to hang this 'morral' next to my father’s, a reminder of the confidence I was given and the Mayan belief that authority is granted to those who have served the community.”

Arévalo’s connection to Guatemala’s democratic past is what makes his desire to work with the United States so extraordinary: It was the CIA that undid his father’s legacy.

A father’s complex history with the U.S.

Like many Guatemalans over 60, Mayra Rodríguez remembers hearing stories about Arévalo’s father and the country’s first democratic “spring.”

“My parents were poor, and they lived through the dictatorship,” said the retired teacher. “My mother and father told us how, when Arévalo won the election, people’s attitudes changed,” Rodríguez said. “They knew they would have a different sort of president.”

Since its independence from Spain in 1821, Guatemala has been ruled by a series of dictators aligned with landowning oligarchs. The oligarchs, in turn, had interests aligned with the profits of the United Fruit Company, a U.S. banana producer that established a powerful fiefdom across Central America.

"United Fruit destabilized democratic frameworks wherever it could, and it ultimately worked best with military dictatorships," said Peter Chapman, author of the 2007 book, "Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World."

When the elder, Juan José Arévalo, became the country’s first democratically elected president in 1944, he ended the violent dictatorship of Jorge Ubico, an army colonel whose 13 years in power were defined by brutality and earned him the nickname "Little Napoleon of the Tropics."

Juan José Arévalo’s democratic reforms were inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. He built schools and hospitals. He gave illiterate Guatemalan men voting rights. He nurtured fledgling unions. His efforts were not universally welcomed.

By the time Arévalo left office in 1951, there had been numerous attempts on his life and plots for his ouster.

A year before he left office, a lobbyist for United Fruit met with an influential State Department official. The lobbyist, according to declassified CIA documents, suggested that the U.S. oust Arévalo, after he had taken too much interest in United Fruit’s exploitative labor practices.

Jacobo Arbenz succeeded him as president, demanding better terms for the rural poor. That move smacked of communism to the Truman administration during the anti-communist fervor of the time. So, the CIA orchestrated a coup to oust Arbenz in 1954. The elder Arévalo was forced to flee Guatemala and his son, Bernardo, was born in exile in Uruguay in 1958.

"The 1954 coup shuts down the possibility for democracy. And it's really the start of a civil war in Guatemala that lasts for 36 years," said Will Freeman, a scholar fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

It’s a memory older generations in Guatemala still carry.

“The reforms his father enacted really made an enormous difference,” said Anita Isaacs, a professor of social science at Haverford College.

“I see the father in the son,” she said. “It’s his message that he is carrying.”

The Biden administration’s ‘root causes’ immigration strategy

Two years ago, Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris laid out a five-point strategy to tackle the “root causes” of migration from Central America, anchored by a $400 million plan to invest in programs to address problems that drive migrants to the U.S. border.

The strategy flatlined: "They came up against, in the case of Guatemala, a corrupt class that just wouldn’t back down," Eric Olson, director of policy for the Seattle International Foundation said. "They found real, strong and deep resistance in the region."

The administration’s “root causes” plan intended to support independent media, strengthen the justice system and prosecute corrupt actors. Instead, Guatemalan prosecutors aggressively pursued the officials leading anti-corruption efforts, and top judges, anti-corruption prosecutors and journalists fled to Mexico and the U.S.

So the Biden administration pivoted, sanctioning allegedly corrupt officials including Consuelo Porras, the country’s attorney general.

Over the next two years, strategy reports from the White House show a different focus. A 2023 announcement trumpets not internal anti-corruption efforts but $1.2 billion in outside private investment.

“We’re certainly clear-eyed that the change doesn't happen overnight,” a State Department official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “These efforts require sustained attention.”

There is no doubt an Arévalo win could open new avenues for the Biden administration, Olson said.

The Biden administration is not taking any public position in the race.

The State Department official rejected any suggestion that the administration has a “preferred candidate” and has instead condemned “election interference” and earlier efforts by Porras and her office to revoke the status of Arévalo’s Semilla party.

“The most important thing for us is a free and fair election and a process that is not undermined by the Guatemalan attorney general or corrupt forces with which she works,” the State Department official said.

In a sign of the election outcome’s significance for the U.S., officials from the State Department, National Security Council and vice president’s office have met with both candidates.

To Biden’s advantage, Arévalo seems to have an agenda that tracks with the White House, even on thorny issues of border enforcement.

Biden rolled out policies making it harder to seek asylum in the U.S.; Arévalo told USA TODAY he intends to crack down on smuggling through his country. Biden has opened “lawful pathways” for migrants to reach the U.S. and increased the availability of work visas; Arévalo thinks he can help.

“We very clearly understand that there are problems with 'coyotes,' a form of organized crime, simply having control of many places at the borders,” Arévalosaid, a problem that an expansion of U.S. work visas could address. “We have been told by U.S. businessmen and by people in the U.S. government as well, that there is a need for workers in the United States.”

“When it comes to Biden's ‘root causes’ strategy, I think Arévalo does seem to be very much on the same page,” said Rachel Schwartz, an expert on Guatemala’s democracy at the University of Oklahoma. “There is a sort of shared understanding of the problem and a shared sense of what the solutions are.”

US worries about Guatemala election interference

Tensions were high in the final days of the Arévalo campaign after an Ecuadorian presidential candidate was assassinated in early August. The brazen attack was captured on cellphone video and circulated on social media. Opponents of Arévalo commented, “and Bernardo when?”

In Guatemala, most presidential candidates travel by helicopter across the hard-to-access countryside: a sign, voters say, they’re in somebody’s debt and subject to corruption.

Arévalo, instead, crisscrossed the country’s mountainous terrain on winding two-lane highways in an older model charcoal-colored Ford SUV, in a convoy of three or four vehicles.

After Quiché, he headed to Huehuetenango state, which shares both a border and a smuggling corridor with Mexico, just to the northwest.

Some 45 police officers secured the perimeter of Arévalo’s rally just outside the walls of a school in the city center. The crowd sandwiched into a side street pumping the white flags of Semilla and purple signs with Arévalo’s name. Balloons and pennants danced in the breeze.

Recent polls of likely voters favor Arévalo to win more than 60% of the vote.

There is a social movement backing him, he said, that includes young people, indigenous people and some in the private sector who want the rule of law respected. “They just didn’t see us coming,” he said.

Arévalounderstands there are no guarantees. His country’s legal system almost thwarted his party’s chances once before. He knows that even if he wins the election, his foes could use the power of the state to attack the outcome in court.

“We know there’s going to be a reaction,” he said.

Women played marimba. Security detail readied the area where Arévalo would arrive, holding bulletproof shields like briefcases. Someone set off firecrackers in a nearby park, the noisy ta-ta-ta-ta drowning out the music as smoke billowed.

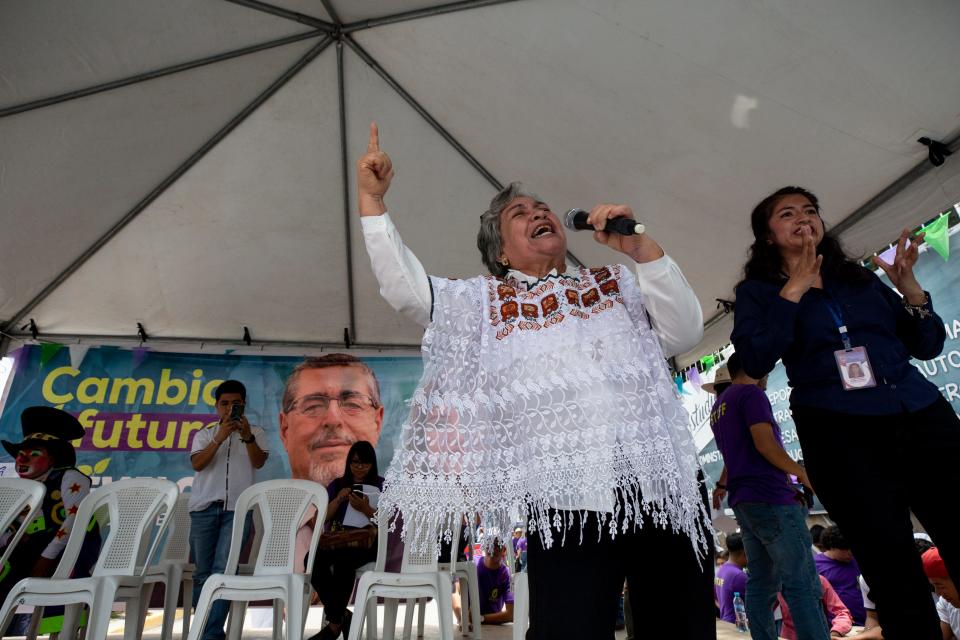

Rodríguez, the retired teacher who remembered her parents’ stories of Guatemala’s first democratic election, waited by the stage, her salt-and-pepper hair brushed back, her white lace "huipil" blouse neatly draped.

Rodríguez watched in awe. She believed Arévalo, like his father before him, would herald a new era where younger generations wouldn’t have to leave Guatemala.

“I am 64 years old,” she said, “and we have lived a very sad story in my country. I have been hoping that the people would wake up. We are hungry for justice. We are hungry for honesty and integrity.”

Local performers took the stage to entertain his supporters while they waited. A clown danced. Campaign volunteers tossed T-shirts into the crowd. A "cumbia" promoting Arévalo played over loudspeakers.

Rodríguez asked for a turn.

She stepped on stage, nervous about remembering the lines of a poem she wished to share. She fumbled with the microphone.

The rally grew quiet as she swayed. The marimbas had gone silent. The green and purple balloons hovered in the humid air.

Then, the words poured out.

“In the darkness of night, we speak of truth and honor. It’s that Arévalo lives again …”

The oration went on. Men and women in the crowd wiped their eyes in silence.

Finally, the poem reached its final line. The city center erupted in cheers.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Guatemala election 2023: Why Bernardo Arevalo could help the US border