How journalists got it wrong about Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens

“Never say you know the last word about any human heart,” the novelist Henry James wrote, but journalists do it all the time anyway. The conventions of the profession more or less demand it: You sit for 90 minutes in a hotel room with an actor, you follow a politician around for a day, then go back to the office to write a profile of affable, avuncular Bill Cosby or earnest, straight-arrow New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

The latest example of a public figure failing to live up to his press is former (as of Friday) Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens, a Rhodes scholar, decorated Navy SEAL, philanthropist and family man. Greitens, who was elected in 2016 in his first try for public office and was already being talked about as a potential president, resigned last week in disgrace. He was facing possible impeachment over allegations, which he has denied, that he blackmailed his mistress to keep their affair secret and, separately, criminal charges related to the financing of his campaign. (The campaign-finance charges were dropped last week when he announced he was stepping down.)

Greitens blamed his troubles on, naturally, a “witch hunt” by his political enemies. That included his fellow Republicans in the Legislature, who in fact didn’t seem to like him very much, probably because he campaigned as an opponent of the entrenched establishment in state government — in other words, themselves. You can’t exactly blame them for taking it personally, considering he ran a campaign ad consisting of 30 seconds of him blasting away with a machine gun. But his downfall is also a cautionary lesson about — and for — the media. Greitens’s failure to live up to his reputation is his own fault, obviously, but does some of the blame rest with those who created that reputation?

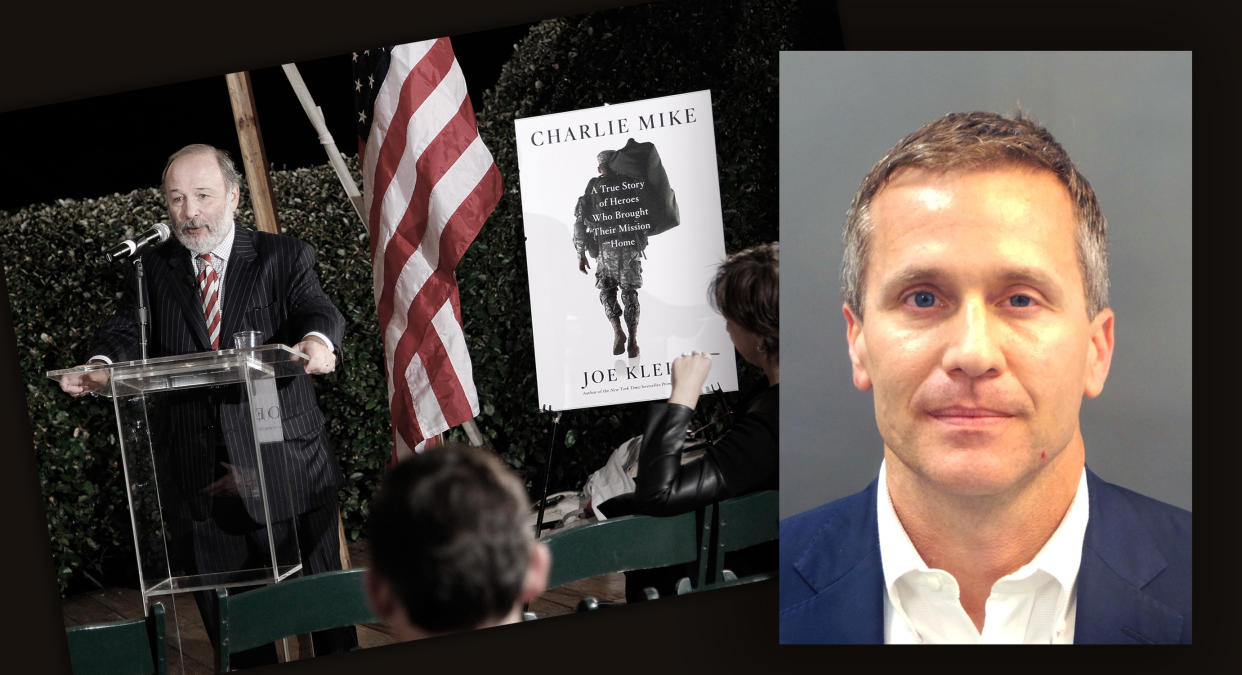

Greitens represents a particularly apt test of this proposition. Even before running for office he was one of Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People, one of Fortune’s 50 Greatest Leaders. Nobody expects profound insights from these lists, of course, but his aura of saintliness was sealed by an entire book — in fact several books, including those he wrote about himself. Notably, he was a leading figure in 2015’s “Charlie Mike” by Joe Klein, which describes how Greitens founded and ran The Mission Continues, a nonprofit that places and sponsors his fellow post-9/11 veterans in community service jobs.

To say that “Charlie Mike” glorifies Greitens is like saying God comes off well in the Bible. He was a prodigy who was able to roll over in his crib at the age of 1 week, a superbly fit athlete who ran double marathons, a scholar who “introduced Mike to his favorite poem by Aeschylus” and started a book group for his SEAL team. A throwback to a less cynical age, someone “intent on living a life of consequence” and at the age of 8 or 9 “the sort of kid who actually said he wanted to be President of the United States” — “because I want to help people,” he clarified.

Klein is a political journalist with a long and impressive resume, including authoring (as “Anonymous”) the Clinton campaign roman à clef “Primary Colors.” (We were colleagues at Newsweek in the 1990s.) A lifetime of exposure to politicians who give the impression of spending their nonworking hours in a closet, waiting for their consultants to let them out and hand them their talking points, breeds cynicism. But also its opposite, a yearning for authenticity, a conviction that virtue can be restored to the republic by candidates who reveal something of themselves, who exhibit sparks of intellectual honesty, emotional authenticity and self-awareness. Unfortunately, that can give rise to the dangerous delusion that the journalist has the ability — indeed, the obligation — to discern that quality. To know another’s heart.

The two outstanding, and opposite, illustrations of this tendency are John McCain and Hillary Clinton. McCain was famous for his accessibility to reporters during his 2000 presidential campaign, for the spontaneous give-and-take of his campaign-bus bull sessions, his forthright expressions of anger and vulnerability. This worked wonders with journalists thrilled to have a flesh-and-blood three-dimensional candidate to cover, and they responded with glowing tributes to his principles and courage — qualities that he indeed possessed, and exhibited from time to time, even while occasionally falling short. Clinton was the opposite, controlled, walled off by aides, with a focus-group-tested answer always at her fingertips. The journalist Amy Chozick’s book, “Chasing Hillary,” was described by one reviewer as “a first-person account of Chozick’s failed 10-year quest to see the ‘real’ Hillary,” a persona as inaccessible as the “real” George Washington.

Klein himself was accused, as he put it, of being “in the tank” for McCain, as well as for George W. Bush and Bill Bradley. Reading his coverage of the 2000 campaign in the New Yorker, and transcripts of his commentary on television, reveals mixed feelings about Bush as a political figure, but affection for him as “a decent fellow,” “a genuinely congenial fellow” who even “betrayed, from time to time, stray wisps of humanity.” In contrast, Klein seemed to hold in disdain Bush’s eventual rival, Al Gore, who came across as wooden and arrogant, “opportunistic, cold, inhumane, probably pretty smart” but not anyone you’d “want to have in your kitchen for the next four years.”

History, I’d say, has rendered a verdict on the wisdom of choosing a president on the basis of “stray wisps of humanity.”

It’s not surprising that Klein was enthusiastic about Greitens, who was indeed an extremely accomplished and impressive person, and the opposite of a bland, programmed professional politician. And, in fact, Klein hasn’t entirely changed his mind. As recently as May 19, he posted on Facebook that while Greitens had made mistakes, including a confessed extramarital affair and using the donor list from The Mission Continues to solicit campaign donations, “he’d been accused of far worse — of tying up, blackmailing and taking nude pictures of the woman with whom he was having an affair. To those of us who know Eric, it seemed ridiculous — and it was.”

Klein may or may not be premature in exonerating Greitens of blackmailing — he was due to go on trial last month on related charges of invasion of privacy, but the case was dropped for procedural reasons and has been referred to a special prosecutor, who may decide to refile the charges. But if all I knew about him was what I read in “Charlie Mike,” I wouldn’t have suspected him capable of the things he did do, including cheating on his marriage.

Klein doesn’t seem to have written anything else in public about Greitens recently, although in an exchange of messages last week he told me he was thinking about it. He added that Greitens’s “ambition led him astray — not an uncommon story.” But “Eric Greitens saved lives, dozens of them, and created a great organization that has brought new life and purpose to thousands of veterans.”

And Klein defends the proposition that journalism can illuminate the character of a subject, provided it’s backed by reporting. When I said I planned to write something I pretentiously described as a “meditation” about Greitens, he responded this way:

“[T]humb-sucking meditations making vast judgments about people you’ve never met is the very worst form of journalism. That’s why I always wrote a reported column.”

I have never met Greitens and so, in deference to my old colleague, I withdraw my thumb from my mouth and disclaim any intention of judging him. My point, however, is about passing judgment on people one has met. I have my share of embarrassing clips in my past, including a cringeworthy profile of a long-ago New York City congressman who resigned a couple of years later facing multiple felony charges, for which he ended up in prison. I spent plenty of time interviewing and traveling with him. I thought I knew him.

I can’t recall a time when journalists have been under such scrutiny as they are now. On behalf of the profession, I reject the wholesale accusations of carelessness, bias and corruption that are being casually thrown around. The writers I have worked with, at Yahoo News and elsewhere, are on the whole honest people doing their best at a difficult job. The lesson I hope both readers and writers take from the coverage of Greitens, and of George W. Bush for that matter, is the danger of thinking you know the last word on any human heart — and of making political judgments on that basis.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Lawyer suing Trump over emoluments expects to see hotel records

More young people plan to vote this year. But their key issues may surprise you.

Disinformation wars: How Ukraine fought the Kremlin’s fake news machine

Detroit’s mayor takes on gentrification as his city bounces back from bankruptcy