Julia Hopper Daniel and her family

Benita Albert brings us insight into a family history that is both unique and typical of other lost or potentially lost histories. Her interest in this family’s history, generated through her story of Molly Brown, takes us back to some of the earliest settlements along the historic early route west, the Emery Road.

The plantation purchased prior to the Civil War begins a history of the family. An original smokehouse and well house still exist there! Now, those structures may well be among the oldest structures in Oliver Springs and should be noted along with such others in the area as the Freels Bend Cabin in Oak Ridge built in 1844, and the Morgan County Stonecipher-Kelly House built in 1814.

You will enjoy this adventure back in the history of our area that is not well known or appreciated nearly as well as it should be. I am pleased to learn of the coming Tri-County African American Cultural Museum in Oliver Springs. Now, learn some history you did not know.

***

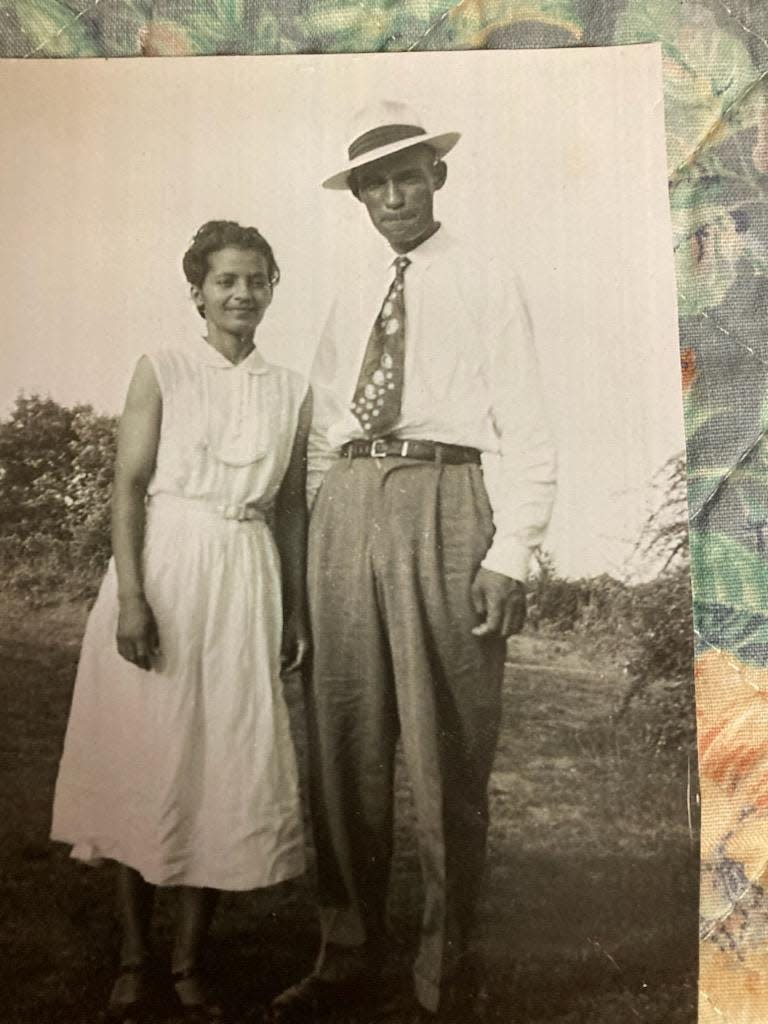

Julia Hopper Daniel is a historian, genealogist, archivist, and an enchanting storyteller. Her Hopper family roots in Oliver Springs date back to the mid-19th century. Her great-great-grandmother Adeline was brought as a 10-year-old slave to work on a plantation in Winters Gap (now called Oliver Springs). The plantation land was purchased in 1855 by William Staples of Morgan County. Adeline remained in the Oliver Springs community until her death at age 84 in 1929. Adeline’s great-grandsons, William Julian Hopper Jr. and Benton Howard Hopper, purchased approximately 200 acres of the original Staples farmland in the late 1940s.

Julia Daniel fondly recalled her early childhood home as a large, wood-framed antebellum home with deep porches, a home that was included in the Hopper land purchase. Though this house was demolished when a new brick rancher was built in 1960, the original plantation smokehouse and well house still exist on the property. Now there are a total of eight family homes sitting alongside fertile cornfields, other vegetable and fruit gardens, and bucolic pastures on the Hopper land located a couple of miles outside of Oliver Springs.

Julia’s brother, William Julian Hopper III, is well known for the truckloads of delicious, Silver Queen corn he sells at the Oak Ridge Farmers Market, an annual tradition since 1967. Julia remembers that the federal government’s “opening of the Oak Ridge gates” in March 1949, provided access to many new customers eager for fresh farm products which the Hopper family often delivered residentially. The family was also well known to Knoxville’s Western Avenue Market, where they delivered fresh produce for over 30 years.

Julia holds in highest esteem her upbringing and the values instilled: close family ties, a strong work ethic, educational goals, and a spiritual foundation. She described her parents, William Julian (June) Hopper Jr. and Nannie Lamar Smith Hopper, as strict disciplinarians, but also as examples of unconditional love and benevolence within the family and beyond.

A charming story, so descriptive of everyday life on the farm in the 1940s was written by Julia’s mother. The story highlighted events of an ordinary workday turned special by the birth of Julia.

“Monday, February 23, 1948, was wash day at the Hopper household. Monday was always wash day unless there was rain. The water was drawn out of a well on the porch and carried to the big tub on the Home Comfort wood and coal cook stove for heating. In those days we washed on a rub board, boiled the white clothes, and rinsed the colored clothes twice. There was no wringer type washing machine let alone an automatic washing machine. They (the family) teased me about going to the Stone Clinic on that day saying I would do anything to get out of helping with the washing.” By the time Julia was born in early afternoon the day’s wash was already drying on the clothesline.

Julia said, “My parents took in many people, extended family and others who worked on the farm. Some lived in three small houses provided on the farm property, but also some boarded in our main house. Momma would cook for all the farm workers preparing hearty meals befitting their big appetites. The children ate last and that meant we sometimes missed out on the tea and cornbread.”

Speaking to her farm tasks, Julia said: “My older sister Abigail and I would deliver heavy glass jars of well water to the field workers, making multiple trips on hot days. I once had the bright idea to cut our walking down by stopping at a closer stream branch to refill. It was muddy water that was not well received and quickly spit out.” At this point in our conversation, Julia confessed to being somewhat of a prankster and a young girl who would rather have been in the field pulling corn, or better yet, driving the mule-drawn wagon.

Stories of her parents included their Sunday afternoon visits to the sick and needy in their Little Leaf Baptist Church family and to neighbors with whom they shared farm goods and prayers. A customer who bought food from Julia’s father recalled his generosity. She remembered that when he learned she was a widow, he quietly filled her sack with extra food at no charge. Nannie became a deaconess in her church and was responsible for preparing the Communion Table. June was a deacon who, along with his brother Benton, served as lead crew members in the construction of the new, brick sanctuary built in 1964.

As early as the 1850s, William Staples wanted his slaves to worship with his family. He provided seating for them in the back of the sanctuary on a raised balcony in the Fairview Church. Adeline first worshipped at Fairview, the church building sitting on a hill above the Staples plantation. Later, Adeline Staples Crozier’s status is recorded as one of the founding members of The Little Leaf Baptist Church. That church today counts seven generations of the Hopper/Crozier clan and extended family who have actively participated in a variety of church leadership roles. Julia Daniel has served faithfully as an archivist of the church history.

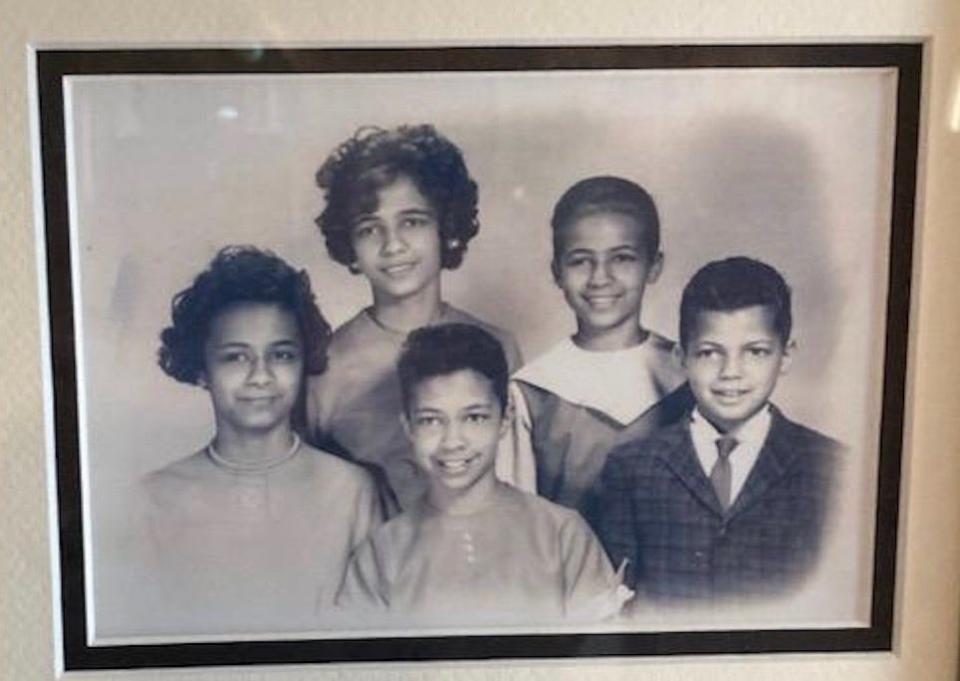

The five Hopper children of June and Nannie are in birth order from oldest to youngest: Abigail (Gail), Julia (Judy) Smith, Minnie Louise (Lou), Anna Jean (Jean), and William Julian III. Two other siblings died at childbirth, Gail is now deceased (2011), while Lou lives in Oak Ridge, and Jean in Smyrna. Both Julia and Julian III, as well as their cousins from Uncle Benton’s family, live on the Hopper farm compound. Julian III continues the tradition of the Hopper farm learned under the tutelage of his father and Uncle Benton.

Julia wrote in a tribute to her Uncle Benton of the strong family ties she knew as a child: “If my Grandmother Hopper (my father’s mother) and Aunt Mamie Lou (my father’s sister) went to the store and bought fresh strawberries or new tomatoes, they would always buy the same for our family. You were just family and that was the way it was. Our Grandmother Hopper would make our clothes; or our Aunt Josephine, or Aunt Sylvestia, or Aunt Gladys would give us clothes. It would be what we called second-hand clothes, or hand-me-downs, or used clothes. I would call them ‘love clothes.’ I wore a beautiful white dress with a bright red sash tied around the waist to all the high school proms I attended. The dress was a hand-me-down family gift, that I dearly loved.” As she related this, Julia’s eyes sparkled with a delightful "belle of the ball" countenance.

Aunt Sylvestia (wife of Benton) hired 12-year-old Julia for her first paid job of babysitting their three youngest children for a week. Julia was shocked when they offered to pay her $5, and after telling them that was too much money, she accepted $3.50. She used the money to purchase her first “store-bought” dresses, one pink with lace accents and the other a sky-blue attire that evoked smiles as Julia described them some six decades later. She praised her Grandmother Hopper’s skilled hands that made many a full skirt, the fashion of the day.

Julia commented, “We did not know we were poor; we had so much love and family support. Our combined family contributions made us largely self-sufficient.”

All Hoppers worked and contributed to the family welfare. Julia listed some farm jobs completed by the children: sewing sausage pockets to be ready for the annual hog slaughter, feeding the livestock, milking cows, churning butter, gathering hen eggs, harvesting, accompanying parents to market and bagging produce or collecting money, and helping can and preserve foods.

“The smokehouse always had hams hanging, the cellar was filled with food for winter, and delicious homemade jams and jellies were preserved. The watermelon patch provided the children’s afternoon snacks. We had everything we needed. We were blessed to have a farm,” Julia reminisced.

Julia’s parents emphasized the importance of education. Her father attended the Oliver Springs Colored School (first established in 1879) for grades one through eight. Subsequently, he traveled to a high school for African American students, The Nelson Merry High School, in Jefferson City. Given that the school was approximately 60 miles from his home, Julian had to board in Jefferson City. He was rarely able to travel home. His high school education ended in his sophomore year due to the sudden death of his father. It was at Nelson Merry that William Hopper Jr. met his future bride, Nannie Lamar Smith. Nannie graduated from high school and attended one semester at Morristown College before she chose to elope and marry William in 1944.

In Oliver Springs, William’s first eight years of education were under legendary teacher Mayme Carmichael, a woman who eventually taught three generations of children. To this day, former students prefer to name their elementary school "Miss Mayme’s School." The one-room schoolhouse provided the elementary schooling for Julia and her siblings.

Julia’s older sister, Gail, enrolled in Campbell High School in Rockwood for her freshman year of 1958-59, followed by Julia two years later. They rode a school bus route with their farm being one of the first, pre-dawn stops followed by numerous other stops for black students across Roane County. Julia chuckled when recalling unscheduled stops for cows crossing the road, sister Gail asking her mother not to be milking the cows where the afternoon bus students might see, and the many new friendship bonds and budding romances made on the long, daily trips. Julia noted that riding a school bus was a big change from their earlier three-mile walks to "Miss Mayme’s School,: walks that required crossing Indian Creek. Fortunately, a kind neighbor provided safe transport via a ride on his mule-drawn wagon when the creek got too high.

Gail graduated as the Campbell High School class valedictorian in 1963. She enrolled in the University of Tennessee in the fall of 1963, two and a half years after UT had admitted the first black undergraduate student in January 1961. Julia was the first of two black students to graduate from Oliver Springs High School in 1965 after Roane County Schools desegregated their student population effective as of Julia’s senior year. Julia’s younger siblings (Lou, Jean, and Julian III) were later Oliver Springs High School graduates. All the Hopper siblings went on to higher education and/or specialized training.

Julia’s father died in 1983 at the early age of 61. His passing was eulogized by a long-time neighbor and friend, the Rev. Kenneth Stubbs. Rev. Stubbs conducted the funeral service in which he often repeated the phrase, “He was a good man.” Using scriptural teachings and words of solace, Rev. Stubbs offered touching observations on the man, nicknamed “June,” and his influence. One of many examples the reverend cited was: “Any time I went somewhere, and I said I live in Oliver Springs; somebody said, ‘Where about?’ I said, ‘Down in the country.’ ‘Anywhere close to my friend June?’ I said, ‘Right below him.’ He left a good testimony behind. … Anything I ever needed he said don’t be afraid to call on me. Any hour, any night, any day, and I don’t think I can say it enough today. … He was a good man.”

Nannie Hopper lived 34more years after her husband’s passing. She took on major responsibilities of the farm aided by her son’s oversight of the daily farm operation. She delighted in the generations of Hoppers to follow and was happiest when feeding large family gatherings at her table. She enthusiastically participated in family reunions of the Hopper and Crozier families. (The Crozier family ancestry dates to Adeline Crozier, Julia’s great-great-grandmother.) Nannie passed her love of family history on to her children.

Nannie’s daughter, Julia, has compiled two large books of family remembrances, each honoring her parents. She has contributed documented narrative to such as: the Crozier family history, to local historical societies, to her church archives, and to newspapers. She has served on the Board of the Oliver Springs Historical Society, is the official historian for Little Leaf Baptist Church, and is president of The Mayme Carmichael School Organization (MCSO). The MCSO mission is to preserve African American history, promote education, and partner with the town of Oliver Springs to develop Carmichael Park.

Julia’s mission does not stop there. Given the vast trove of information she and other interested citizenry have uncovered, her plans are to offer a place for the public to visit and explore and contribute their own knowledge of the region’s African American history. Look for the opening of the Tri-County African American Cultural Museum in Oliver Springs in 2023. The museum’s development is Julia’s current passion - to share the story of the contributions of African Americans who lived, worked, and grew family roots in the adjoining counties of Roane, Anderson, and Morgan. It is a massive undertaking, yet an important and overlooked history hungry for the telling. Additional information on the soon-to-open museum will be included in the second installment of Julia’s story to follow.

***

Thank you, Benita, for a great insightful look into the history of a unique family in our area. All too often overlooked, such history is valuable, and you have captured it in a wonderful manner. I am sure we all look forward to the second and final part of this story, as well as the opening of the Tri-County African American Cultural Museum.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Julia Hopper Daniel and her family