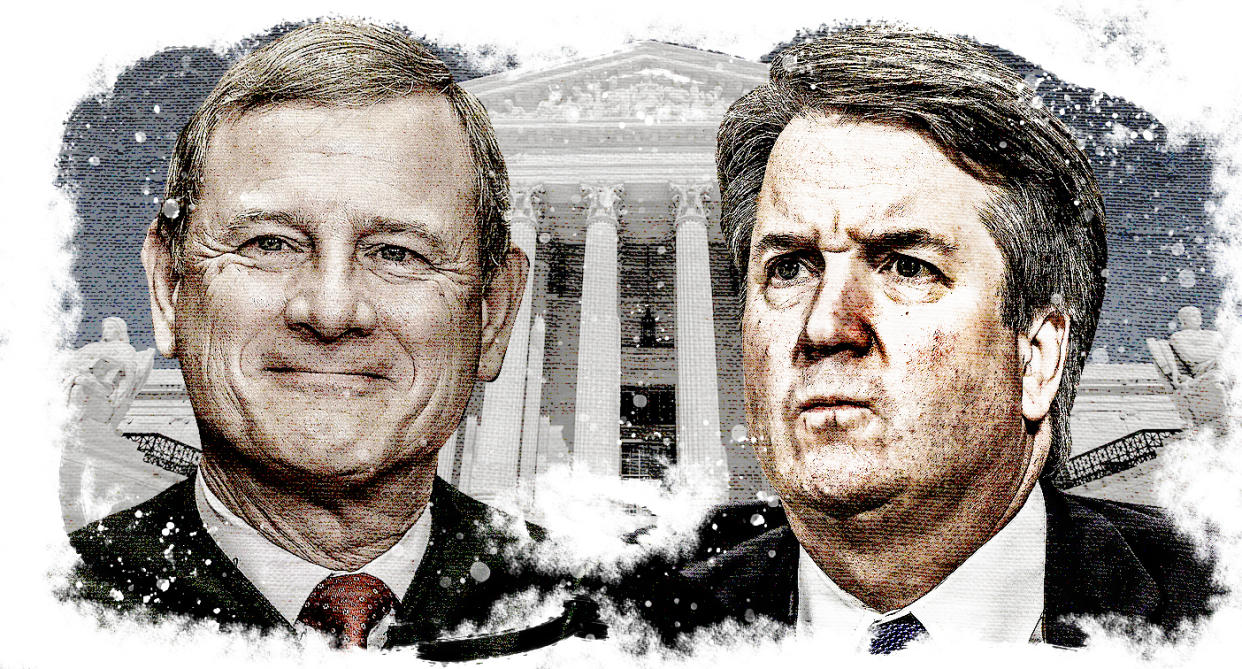

How Kavanaugh could threaten the hard-won legitimacy of the Roberts court

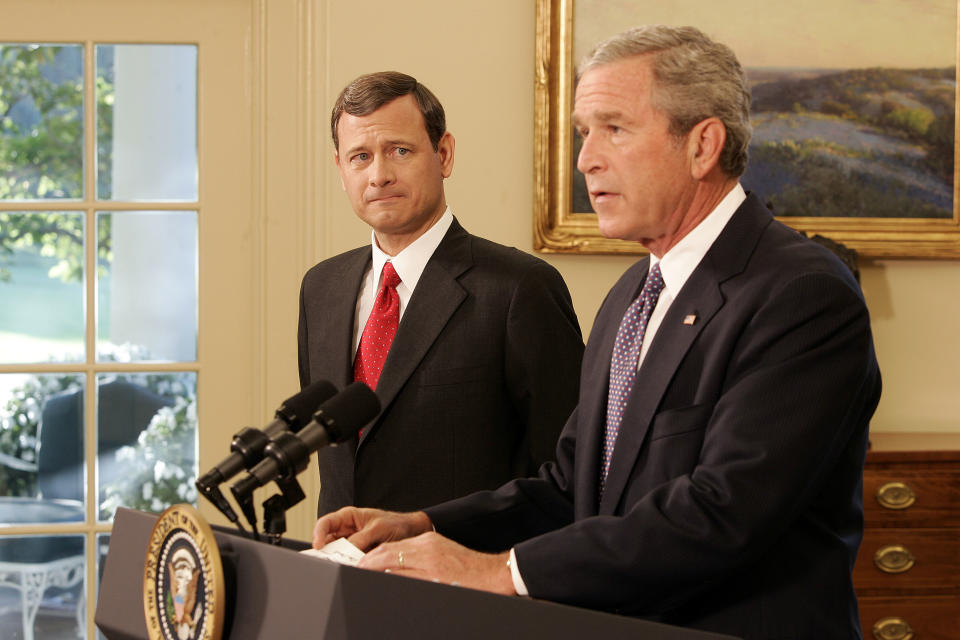

WASHINGTON — Sitting before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2005, John Roberts, then a 50-year-old aspirant to the Supreme Court, promised “to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat,” should he be confirmed.

“I think that is not a good development to regard the courts as simply an extension of the political process,” said the Ivy League-educated judge who was then on the D.C. Circuit Court. “That’s not what they are.”

Picked by President George W. Bush to serve as the chief justice of the Supreme Court after the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Roberts was confirmed with 78 votes in the Senate.

Roberts has labored for the past 13 years to keep the judiciary branch as a sacrosanct institution, able to rule on the most contentious issues of the day — guns, abortion, health care — without succumbing to the vitriol of presidential and congressional politics. That has sometimes led Roberts to put aside his own conservative conviction, most notably in his 2012 defense of the Affordable Care Act in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius.

Though he has also sided plenty of times with the court’s conservative bloc, his relative moderation suggests that the umpire imagery of his confirmation hearing was not merely vote-seeking rhetoric. An analysis of his decisions by the polling and politics site FiveThirtyEight even wondered if Roberts was “a secret liberal.”

But now comes another young and pedigreed D.C. Circuit Court judge, one who could largely undo the credibility of the Roberts court by turning it into a more ideological institution, one no longer trusted by many Americans. In his initial confirmation hearings in September, Brett Kavanaugh deployed precisely the same baseball image that Roberts had before him, casting himself as a constitutionalist with a profound respect for judicial precedent.

Few remember those avowals of neutrality now. What many won’t forget is the furious Kavanaugh who appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Sept. 27 to rebut accusations of sexual misconduct made by Christine Blasey Ford and other women. He did so largely by lashing out at the Democratic legislators seated before him, accusing them of conspiring against his nomination. “What goes around comes around,” he threatened.

President Trump loved Kavanaugh’s anger, but many others did not, even as Republicans pushed forward with the nomination. Earlier this week, retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens called Kavanaugh unfit to serve on the Supreme Court because of his politically charged comments in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Apparently aware of how his testimony has come to be perceived outside the ranks of Trump loyalists, Kavanaugh himself wrote an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal in which he expressed regret for the tenor of those proceedings.

Still, the question remains, now that Kavanaugh has been all but confirmed to the Supreme Court: Where, exactly, will he take the institution? Will he integrate smoothly into the institution, or will he attempt to steer it in the direction of his ideological supports at the Heritage Foundation and the Federalist Society?

“Roberts is very worried about the integrity of his institution,” says Laura Kalman, a legal historian at the University of California at Santa Barbara. “Kavanaugh made Clarence Thomas look like a model of decorum,” Kalman says, referencing that earlier contentious nomination process, in which Thomas, accused of sexual misconduct by Anita Hill, depicted himself as the victim of a “high-tech lynching.”

Kavanaugh, says Kalman, will have a hard time convincing Roberts and the other seven justices that he is not a political operative looking to avenge his treatment at Democrats’ hands.

“Can any labor at this point make the American people think the court is above politics?” Kalman asks. “I don’t see it happening.”

Kavanaugh will replace Anthony Kennedy, who retired last summer. Though Kennedy he was nominated by Ronald Reagan, he sometimes sided with his liberal colleagues on the court, perhaps most notably on same-sex marriage in 2015. Kennedy reportedly favored the selection of Kavanaugh by Trump, yet nobody expects that Kavanaugh will occupy the same centrist position that Kennedy did.

“A Justice Kavanaugh has already signaled that he would be significantly more ideological in his opinions than Justice Kennedy,” says Maya Wiley, an MSNBC legal analyst and former counsel to the mayor of New York City, Bill de Blasio, citing Garza v. Hargan, the case involving a 17-year-old undocumented immigrant in Texas who was seeking an abortion. “Just consider his radical ruling that the government could refuse a young immigrant an abortion, even though all parties agreed she had a legal right to abort her pregnancy.”

Kavanaugh’s dissent in the Garza case, some say, was written in a manner calculated to gain favor with conservative activists. If that was the case, it worked. Three weeks after the ruling, Kavanaugh was announced as a potential future Trump nominee to the Supreme Court. Eight months later, Kennedy retired, paving the way to the Kavanaugh nomination — and a potential reframing of the Roberts court.

Sensitive to suggestions that his court has been infiltrated by a political operative, Roberts could shift left “to preserve the legitimacy of the court,” says legal scholar Kalman. She points to Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who resisted President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s scheme to add six justices the Supreme Court. Hughes also struck down key provisions of the New Deal, which Roosevelt’s detractors depicted as liberal overreach.

The most consequential chief justice following Hughes was Earl Warren, whose background was nakedly political, as he had been the Republican governor of California. President Eisenhower nominated him to the court in 1953. The 15-year-long Warren court marked a period of progressive rulings, most notably in Brown v. Board of Education, which stuck down legal school segregation.

At the same time, Kalman argues, Warren did not want to be seen as an unrestrained liberal. His ruling in Terry v. Ohio, a 1968 case involving police stops, saw the chief justice, then on the cusp of retiring, taking a “much tougher stand on law and order” than might have been expected.

Because they are appointed for life, Supreme Court justices “have thought about their place in history probably more than any other officer in America other than the president — and maybe more so,” says Jed Shugerman, a legal scholar at Fordham University. Shugerman calls Roberts an “incrementalist” who is “turned off by ideological overreach.” Shugerman had been hoping that Roberts, horrified by the prospect of having Kavanaugh as a colleague, would encourage the nominee to withdraw. “This is an extraordinary moment, but extraordinary moments call for extraordinary leadership,” Shugerman said as the full Senate prepared to vote on Kavanaugh.

Supporters of Kavanaugh point to a record in keeping with Trump’s limited-government vision. Andrew Grossman, a Washington lawyer at the firm Baker Hostetler who has made the case for Kavanaugh in the Wall Street Journal, explains that “Kavanaugh made his mark in the law as a scholar of the law governing the administrative state, and his most celebrated decisions are those working through the application of the constitutional separation of powers in our current age. For the past decade, the Court has been on the verge of reconceptualizing the role of the bureaucracy in constitutional government, and a Justice Kavanaugh would be poised to lead that charge.” That, of course, is precisely what worries Kavanaugh’s detractors.

Assuming Kavanaugh is confirmed by the full chamber — a near certainty — it’s unclear how Roberts will welcome, and manage, the least popular and most controversial Supreme Court justice in modern American history. But it could be more important to the legacy of the Roberts court than any single ruling.

“This is a test for the legacy of Chief Justice Roberts,” says Daniel Goldberg of Alliance for Justice, a progressive group that has opposed the Kavanaugh confirmation. “It is his name on the court.”

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court:

‘Things happened in the ’80s’: Women Trump fans explain their faith in Brett Kavanaugh

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: There’s no basis to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

Confusion, chaos hit Capitol Hill in wake of FBI report on Kavanaugh

Yahoo News explains: Who is allowed to see the Kavanaugh FBI report?

‘Boofing’ and ‘ralphing’ and other doubts about Kavanaugh’s testimony